中国的气候和能源政策呈现出一种悖论:在以惊人的速度发展清洁能源的同时,也未停下新建燃煤电厂的步伐。

仅在2023年,中国就新建了70吉瓦(GW)的煤电装机容量,比2019年增长了四倍,占当年全球新增煤电装机容量的95%。

煤电产能的激增引发了人们对中国二氧化碳(CO2)排放和气候目标能否实现,以及对未来出现搁浅资产风险的担忧。

由于光伏和风能发电量不稳定,中国政府将煤炭作为保障能源安全和满足快速增长的用电高峰的手段。

与此同时,中国的电力行业在成本、需求模式、监管和市场运作方面正在发生重大变化。我们的新研究表明,用于证明新煤炭产能合理性的传统经济计算方式可能已经过时。

我们使用一个简单的分析指标来评估能满足用电高峰需求的最经济方式是什么。结果表明,光伏加电池储能的组合可能是比新建煤电更具成本效益的选择。

中国电力格局发生了怎样的变化?

在过去十年里,可再生能源和电池储能的成本大幅下降,高峰时段的住宅和商业用电需求激增,电力交易市场获得了更大的吸引力。

与此同时,中国还宣布了“双碳”目标,即在2030年前实现碳达峰、2060年前实现碳中和。鉴于这些转型,建设更多未减排的煤电厂与中国的长期气候承诺相冲突,而且对满足用电需求对增长来说,可能不再是最具成本效益的选择。它还占用了清洁能源系统转型急需的资金。

替代指标如何评估成本?

我们的研究引入了一种替代指标,用于计算在满足不断增长的高峰用电需求的情况下,所需的最优成本投资。

这一指标,即“净容量成本”(net capacity cost),是满足用电高峰需求所需的基础设施投资的年化固定成本,减去该设施带给电力市场的收入,或其“系统价值”(system value)。 在该指标中,负数意味着这些投资将带来利润,而非支出。

为了探索在中国使用的情境,我们使用了一个简单的例子:在一个假定省份,高峰用电需求增加了1500兆瓦(MW)、全年需求增加了6570吉瓦时(GWh)。

然后,我们概述了满足高峰和全年能源需求的五种策略(情况),其涵盖了从严重依赖煤电到光伏和电池储能相结合的方式。

在不同的案例中,资源衡量的规模基于它们能够可靠地满足高峰供应需求和年度能源需求的程度。

- 情况1:新的煤炭发电能力可满足高峰和年度能源需求的所有增长。

- 情况2:光伏可满足70%的年度能源需求增长,煤炭可满足30%的年度能源需求增长;光伏可满足525兆瓦的高峰供应需求(由于光伏发电可能不在高峰期间,因此基于“容量可信度”进行折减),而煤电可提供剩余的975兆瓦。

- 情况3:光伏可满足所有年度能源需求增长;光伏和煤炭均可满足750兆瓦的高峰供应需求,同样通过容量可信度对光伏发电量进行折减。

- 情况4:光伏满足所有年度能源需求增长;光伏和电池均为高峰供电需求提供750兆瓦;电池提供调频储备(用于管理精确至分钟的供需差异的备用电源)。

- 情况5:光伏满足所有年度能源需求增长;广泛和电池均为高峰供电需求提供750兆瓦;电池提供能源套利(在价格或成本较低时充电,在价格或成本较高时放电)。

如下图所示,我们针对每种情况都计算了单个资源(煤、电池或光伏),以及整个系统每年获得1千瓦(kW)发电容量的年净成本,单位为人民币元。

表上半部分的资源净容量成本是指该资源的净成本(即年化固定成本减去该资源从提供能源和辅助服务,如调频,所获得的年收入)。正数表示电网运营商在增加或获取该资源时的净成本。

表下半部分的系统总净容量成本,是在每种情况下利用资源组合满足高峰需求增长的净成本。

我们用于计算系统净成本的权重是基于装机容量与高峰需求增长的比率。

不同能源组合满足用电需求的成本

| 情况 1 | 情况 2 | 情况 3 | 情况 4 | 情况 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 资源净容量成本 (元/千瓦/年, 每千瓦装机容量) | |||||

| 煤炭 | 424 | 424 | 512 | ||

| 电池 | 248 | 781 | |||

| 光伏 | -128 | -128 | -128 | -128 | |

| 系统净容量成本 (元/千瓦/年, 每千瓦满足高峰用电需求且折减容量可信度后) | |||||

| 煤炭 | 471 | 306 | 236 | ||

| 电池 | 138 | 434 | |||

| 光伏 | -223 | -319 | -319 | -319 | |

| 总计 | 471 | 83 | -83 | -181 | 115 |

为了对这一简单分析进行压力测试,我们研究了不同来源的各种价格的敏感性。

由于中国的光伏价格已经很低,我们的敏感性分析主要集中在煤炭、电池和其他分析所需投入的价格上。

满足高峰用电需求最经济的方法是什么?

我们的结果表明,当电池储能提供调频储备时(情况4),光伏和储能的组合是满足高峰用电需求增长最具成本效益的选择。

在这种组合下,每获得1千瓦发电装机容量,电网运营商的成本为-181元(约-25美元或-20英镑)。

相比之下,新建煤电产能以满足高峰用电需求增长(情况1)是最昂贵的方案,每获得1千瓦装机容量的净容量成本为471元(约合65美元或52英镑)。

情况3,即大型煤电厂仅用作备用电源(几乎不发电),在中国可能出于政治原因而至少在短期内不可行。

另外两种情况(情况2和情况5)更具可比性,但鉴于自本分析报告发布以来,电池价格下降了30%以上,约为每瓦时(Wh)1元人民币(约合0.14美元或0.11英镑),因此情况5中的电池可能比情况2中的煤炭更具经济吸引力。

我们的解决方案如何助力中国实现气候目标?

我们的分析表明,为了应对不断变化的形势,在满足中国日益增长的能源需求的同时,实现其气候目标的近期战略是将电池储能纳入电力市场。

目前,中国政府允许包括电池在内的“新型储能”参与电力市场。然而,详细规定尚不明确,电池的参与可以更简单。

例如,电池储能不被允许提供“运转储备”,即为应对意外的供需误差所预留的发电量。如果允许电池储能提供运转储备,将增强其商业价值。

允许电池储能更多地参与市场将促进电池储能系统的持续创新和降低成本,同时为系统运营商提供宝贵的运营经验。

这种策略将与市场效益相符,并反映美国和欧洲近期的电力市场经验。

这也将有助于解决近期的产能和能源需求,因为电池和光伏发电通常比燃煤电厂的建设速度更快。

此外,它还有助于缓解未来新增燃煤发电与可再生能源之间的冲突。主要作为可再生能源发电备用电源的新建燃煤电厂要么很少运营,要么侵占了其他现有煤炭发电厂的运营时间和净收入,从而产生新搁浅资产的风险。

通过继续进行电力市场改革,也将促进对可再生能源发电和电力储存进行更有效的投资。

允许市场制定批发市场电价、允许可再生能源发电和电力储存参与批发市场,这可以提高其收入和利润。

此外,改革还将鼓励高效利用储能,这是我们的关键发现。储能可以为电力系统提供多种功能;批发电价有助于引导储能运营以最低的成本实现具有最高价值的功能。

中国国家能源局最近发出指令,要求将新型储能设施(非抽水蓄能)纳入电网调度运行,这是向我们概述的改革迈出的一步。

可能需要进一步确定适当的补偿机制,例如在某些省份对此类储能设施提供的所有服务进行容量补偿,以促进这些储能设施的可持续发展和并网。

最后,仅靠增加供应不太可能成为满足中国电力需求增长的最低成本方式。提高终端使用效率和“需求响应”也有助于降低供电的总体成本。

随着中国电力市场改革的不断深入,连接多个省份的区域市场设计,以及鼓励省份间资源共享的区域资源充裕性规划,也有助于以最具成本效益和最低碳的方式满足中国不断增长的用电量和高峰需求。

The post 嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠” appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

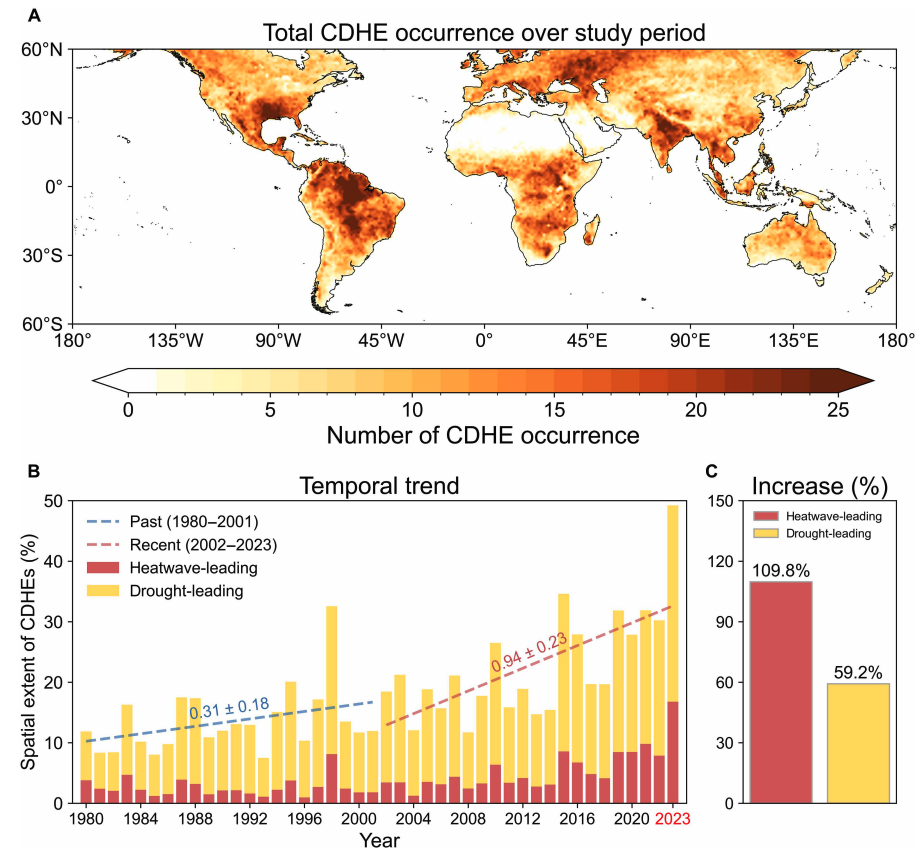

Drought and heatwaves occurring together – known as “compound” events – have “surged” across the world since the early 2000s, a new study shows.

Compound drought and heat events (CDHEs) can have devastating effects, creating the ideal conditions for intense wildfires, such as Australia’s “Black Summer” of 2019-20 where bushfires burned 24m hectares and killed 33 people.

The research, published in Science Advances, finds that the increase in CDHEs is predominantly being driven by events that start with a heatwave.

The global area affected by such “heatwave-led” compound events has more than doubled between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, the study says.

The rapid increase in these events over the last 23 years cannot be explained solely by global warming, the authors note.

Since the late 1990s, feedbacks between the land and the atmosphere have become stronger, making heatwaves more likely to trigger drought conditions, they explain.

One of the study authors tells Carbon Brief that societies must pay greater attention to compound events, which can “cause severe impacts on ecosystems, agriculture and society”.

Compound events

CDHEs are extreme weather events where drought and heatwave conditions occur simultaneously – or shortly after each other – in the same region.

These events are often triggered by large-scale weather patterns, such as “blocking” highs, which can produce “prolonged” hot and dry conditions, according to the study.

Prof Sang-Wook Yeh is one of the study authors and a professor at the Ewha Womans University in South Korea. He tells Carbon Brief:

“When heatwaves and droughts occur together, the two hazards reinforce each other through land-atmosphere interactions. This amplifies surface heating and soil moisture deficits, making compound events more intense and damaging than single hazards.”

CDHEs can begin with either a heatwave or a drought.

The sequence of these extremes is important, the study says, as they have different drivers and impacts.

For example, in a CDHE where the heatwave was the precursor, increased direct sunshine causes more moisture loss from soils and plants, leading to a drought.

Conversely, in an event where the drought was the precursor, the lack of soil moisture means that less of the sun’s energy goes into evaporation and more goes into warming the Earth’s surface. This produces favourable conditions for heatwaves.

The study shows that the majority of CDHEs globally start out as a drought.

In recent years, there has been increasing focus on these events due to the devastating impact they have on agriculture, ecosystems and public health.

In Russia in the summer of 2010, a compound drought-heatwave event – and the associated wildfires – caused the death of nearly 55,000 people, the study notes.

The record-breaking Pacific north-west “heat dome” in 2021 triggered extreme drought conditions that caused “significant declines” in wheat yields, as well as in barley, canola and fruit production in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, says the study.

Increasing events

To assess how CDHEs are changing, the researchers use daily reanalysis data to identify droughts and heatwaves events. (Reanalysis data combines past observations with climate models to create a historical climate record.) Then, using an algorithm, they analyse how these events overlap in both time and space.

The study covers the period from 1980 to 2023 and the world’s land surface, excluding polar regions where CDHEs are rare.

The research finds that the area of land affected by CDHEs has “increased substantially” since the early 2000s.

Heatwave-led events have been the main contributor to this increase, the study says, with their spatial extent rising 110% between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, compared to a 59% increase for drought-led events.

The map below shows the global distribution of CDHEs over 1980-2023. The charts show the percentage of the land surface affected by a heatwave-led CDHE (red) or a drought-led CDHE (yellow) in a given year (left) and relative increase in each CDHE type (right).

The study finds that CDHEs have occurred most frequently in northern South America, the southern US, eastern Europe, central Africa and south Asia.

Threshold passed

The authors explain that the increase in heatwave-led CDHEs is related to rising global temperatures, but that this does not tell the whole story.

In the earlier 22-year period of 1980-2001, the study finds that the spatial extent of heatwave-led CDHEs rises by 1.6% per 1C of global temperature rise. For the more-recent period of 2022-23, this increases “nearly eightfold” to 13.1%.

The change suggests that the rapid increase in the heatwave-led CDHEs occurred after the global average temperature “surpasse[d] a certain temperature threshold”, the paper says.

This threshold is an absolute global average temperature of 14.3C, the authors estimate (based on an 11-year average), which the world passed around the year 2000.

Investigating the recent surge in heatwave-leading CDHEs further, the researchers find a “regime shift” in land-atmosphere dynamics “toward a persistently intensified state after the late 1990s”.

In other words, the way that drier soils drive higher surface temperatures, and vice versa, is becoming stronger, resulting in more heatwave-led compound events.

Daily data

The research has some advantages over other previous studies, Yeh says. For instance, the new work uses daily estimations of CDHEs, compared to monthly data used in past research. This is “important for capturing the detailed occurrence” of these events, says Yeh.

He adds that another advantage of their study is that it distinguishes the sequence of droughts and heatwaves, which allows them to “better understand the differences” in the characteristics of CDHEs.

Dr Meryem Tanarhte is a climate scientist at the University Hassan II in Morocco, and Dr Ruth Cerezo Mota is a climatologist and a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Both scientists, who were not involved in the study, agree that the daily estimations give a clearer picture of how CDHEs are changing.

Cerezo-Mota adds that another major contribution of the study is its global focus. She tells Carbon Brief that in some regions, such as Mexico and Africa, there is a lack of studies on CDHEs:

“Not because the events do not occur, but perhaps because [these regions] do not have all the data or the expertise to do so.”

However, she notes that the reanalysis data used by the study does have limitations with how it represents rainfall in some parts of the world.

Compound impacts

The study notes that if CDHEs continue to intensify – particularly events where heatwaves are the precursors – they could drive declining crop productivity, increased wildfire frequency and severe public health crises.

These impacts could be “much more rapid and severe as global warming continues”, Yeh tells Carbon Brief.

Tanarhte notes that these events can be forecasted up to 10 days ahead in many regions. Furthermore, she says, the strongest impacts can be prevented “through preparedness and adaptation”, including through “water management for agriculture, heatwave mitigation measures and wildfire mitigation”.

The study recommends reassessing current risk management strategies for these compound events. It also suggests incorporating the sequences of drought and heatwaves into compound event analysis frameworks “to enhance climate risk management”.

Cerezo-Mota says that it is clear that the world needs to be prepared for the increased occurrence of these events. She tells Carbon Brief:

“These [risk assessments and strategies] need to be carried out at the local level to understand the complexities of each region.”

The post Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 6 March 2026: Iran energy crisis | China climate plan | Bristol’s ‘pioneering’ wind turbine

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Energy crisis

ENERGY SPIKE: US-Israeli attacks on Iran and subsequent counterattacks across the Middle East have sent energy prices “soaring”, according to Reuters. The newswire reported that the region “accounts for just under a third of global oil production and almost a fifth of gas”. The Guardian noted that shipping traffic through the strait of Hormuz, which normally ferries 20% of the world’s oil, “all but ground to a halt”. The Financial Times reported that attacks by Iran on Middle East energy facilities – notably in Qatar – triggered the “biggest rise in gas prices since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine”.

‘RISK’ AND ‘BENEFITS’: Bloomberg reported on increases in diesel prices in Europe and the US, speculating that rising fuel costs could be “a risk for president Donald Trump”. US gas producers are “poised to benefit from the big disruption in global supply”, according to CNBC. Indian government sources told the Economic Times that Russia is prepared to “fulfil India’s energy demands”. China Daily quoted experts who said “China’s energy security remains fundamentally unshaken”, thanks to “emergency stockpiles and a wide array of import channels”.

‘ESSENTIAL’ RENEWABLES: Energy analysts said governments should cut their fossil-fuel reliance by investing in renewables, “rather than just seeking non-Gulf oil and gas suppliers”, reported Climate Home News. This message was echoed by UK business secretary Peter Kyle, who said “doubling down on renewables” was “essential” amid “regional instability”, according to the Daily Telegraph.

China’s climate plan

PEAK COAL?: China has set out its next “five-year plan” at the annual “two sessions” meeting of the National People’s Congress, including its climate strategy out to 2030, according to the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post. The plan called for China to cut its carbon emissions per unit of gross domestic product (GDP) by 17% from 2026 to 2030, which “may allow for continued increase in emissions given the rate of GDP growth”, reported Reuters. The newswire added that the plan also had targets to reach peak coal in the next five years and replace 30m tonnes per year of coal with renewables.

ACTIVE YET PRUDENT: Bloomberg described the new plan as “cautious”, stating that it “frustrat[es] hopes for tighter policy that would drive the nation to peak carbon emissions well before president Xi Jinping’s 2030 deadline”. Carbon Brief has just published an in-depth analysis of the plan. China Daily reported that the strategy “highlights measures to promote the climate targets of peaking carbon dioxide emissions before 2030”, which China said it would work towards “actively yet prudently”.

Around the world

- EU RULES: The European Commission has proposed new “made in Europe” rules to support domestic low-carbon industries, “against fierce competition from China”, reported Agence France-Presse. Carbon Brief examined what it means for climate efforts.

- RECORD HEAT: The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has said there is a 50-60% chance that the El Niño weather pattern could return this year, amplifying the effect of global warming and potentially driving temperatures to “record highs”, according to Euronews.

- FLAGSHIP FUND: The African Development Bank’s “flagship clean energy fund” plans to more than double its financing to $2.5bn for African renewables over the next two years, reported the Associated Press.

- NO WITHDRAWAL: Vanuatu has defied US efforts to force the Pacific-island nation to drop a UN draft resolution calling on the world to implement a landmark International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruling on climate, according to the Guardian.

98

The number of nations that submitted their national reports on tackling nature loss to the UN on time – just half of the 196 countries that are part of the UN biodiversity treaty – according to analysis by Carbon Brief.

Latest climate research

- Sea levels are already “much higher than assumed” in most assessments of the threat posed by sea-level rise, due to “inadequate” modelling assumptions | Nature

- Accelerating human-caused global warming could see the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C limit crossed before 2030 | Geophysical Research Letters covered by Carbon Brief

- Future “super El Niño events” could “significantly lower” solar power generation due to a reduction in solar irradiance in key regions, such as California and east China | Communications Earth & Environment

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

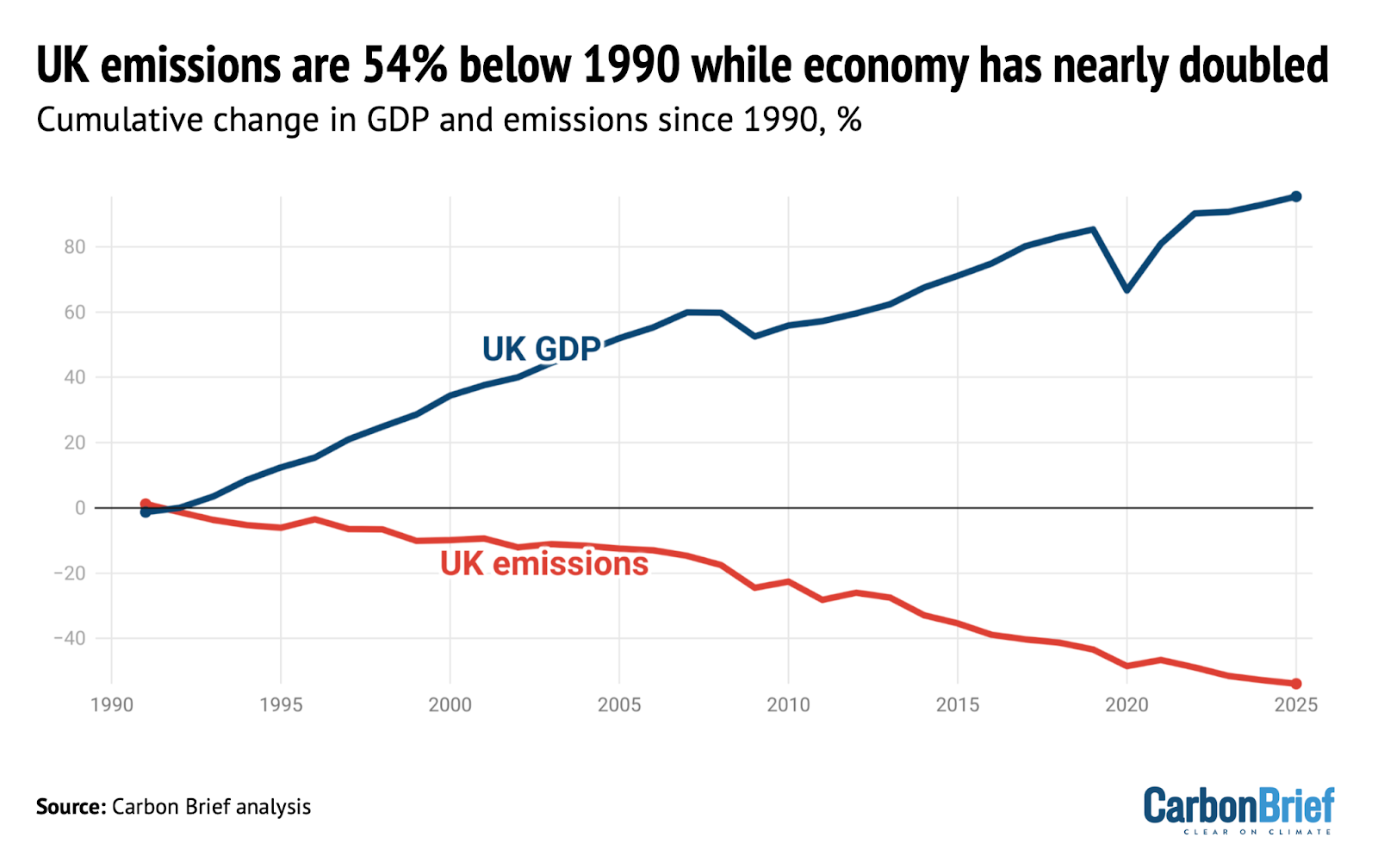

UK greenhouse gas emissions in 2025 fell to 54% below 1990 levels, the baseline year for its legally binding climate goals, according to new Carbon Brief analysis. Over the same period, data from the World Bank shows that the UK’s economy has expanded by 95%, meaning that emissions have been decoupling from growth.

Spotlight

Bristol’s ‘pioneering’ community wind turbine

Following the recent launch of the UK government’s local power plan, Carbon Brief visits one of the country’s community-energy success stories.

The Lawrence Weston housing estate is set apart from the main city of Bristol, wedged between the tree-lined grounds of a stately home and a sprawl of warehouses and waste incinerators. It is one of the most deprived areas in the city.

Yet, just across the M5 motorway stands a structure that has brought the spoils of the energy transition directly to this historically forgotten estate – a 4.2 megawatt (MW) wind turbine.

The turbine is owned by local charity Ambition Lawrence Weston and all the profits from its electricity sales – around £100,000 a year – go to the community. In the UK’s local power plan, it was singled out by energy secretary Ed Miliband as a “pioneering” project.

‘Sustainable income’

On a recent visit to the estate by Carbon Brief, Ambition Lawrence Weston’s development manager, Mark Pepper, rattled off the story behind the wind turbine.

In 2012, Pepper and his team were approached by the Bristol Energy Cooperative with a chance to get a slice of the income from a new solar farm. They jumped at the opportunity.

“Austerity measures were kicking in at the time,” Pepper told Carbon Brief. “We needed to generate an income. Our own, sustainable income.”

With the solar farm proving to be a success, the team started to explore other opportunities. This began a decade-long process that saw them navigate the Conservative government’s “ban” on onshore wind, raise £5.5m in funding and, ultimately, erect the turbine in 2023.

Today, the turbine generates electricity equivalent to Lawrence Weston’s 3,000 households and will save 87,600 tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) over its lifetime.

‘Climate by stealth’

Ambition Lawrence Weston’s hub is at the heart of the estate and the list of activities on offer is seemingly endless: birthday parties, kickboxing, a library, woodworking, help with employment and even a pop-up veterinary clinic. All supported, Pepper said, with the help of a steady income from community-owned energy.

The centre itself is kitted out with solar panels, heat pumps and electric-vehicle charging points, making it a living advertisement for the net-zero transition. Pepper noted that the organisation has also helped people with energy costs amid surging global gas prices.

Gesturing to the England flags dangling limply on lamp posts visible from the kitchen window, he said:

“There’s a bit of resentment around immigration and scarcity of materials and provision, so we’re trying to do our bit around community cohesion.”

This includes supper clubs and an interfaith grand iftar during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

Anti-immigration sentiment in the UK has often gone hand-in-hand with opposition to climate action. Right-wing politicians and media outlets promote the idea that net-zero policies will cost people a lot of money – and these ideas have cut through with the public.

Pepper told Carbon Brief he is sympathetic to people’s worries about costs and stressed that community energy is the perfect way to win people over:

“I think the only way you can change that is if, instead of being passive consumers…communities are like us and they’re generating an income to offset that.”

From the outset, Pepper stressed that “we weren’t that concerned about climate because we had other, bigger pressures”, adding:

“But, in time, we’ve delivered climate by stealth.”

Watch, read, listen

OIL WATCH: The Guardian has published a “visual guide” with charts and videos showing how the “escalating Iran conflict is driving up oil and gas prices”.

MURDER IN HONDURAS: Ten years on from the murder of Indigenous environmental justice advocate Berta Cáceres, Drilled asked why Honduras is still so dangerous for environmental activists.

TALKING WEATHER: A new film, narrated by actor Michael Sheen and titled You Told Us To Talk About the Weather, aimed to promote conversation about climate change with a blend of “poetry, folk horror and climate storytelling”.

Coming up

- 8 March: Colombia parliamentary election

- 9-19 March: 31st Annual Session of the International Seabed Authority, Kingston, Jamaica

- 11 March: UN Environment Programme state of finance for nature 2026 report launch

Pick of the jobs

- London School of Economics and Political Science, fellow in the social science of sustainability | Salary: £43,277-£51,714. Location: London

- NORCAP, innovative climate finance expert | Salary: Unknown. Location: Kyiv, Ukraine

- WBHM, environmental reporter | Salary: $50,050-$81,330. Location: Birmingham, Alabama, US

- Climate Cabinet, data engineer | Salary: hourly rate of $60-$120 per hour. Location: Remote anywhere in the US

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 6 March 2026: Iran energy crisis | China climate plan | Bristol’s ‘pioneering’ wind turbine appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Q&A: What does China’s 15th ‘five-year plan’ mean for climate change?

China’s leadership has published a draft of its 15th five-year plan setting the strategic direction for the nation out to 2030, including support for clean energy and energy security.

The plan sets a target to cut China’s “carbon intensity” by 17% over the five years from 2026-30, but also changes the basis for calculating this key climate metric.

The plan continues to signal support for China’s clean-energy buildout and, in general, contains no major departures from the country’s current approach to the energy transition.

The government reaffirms support for several clean-energy industries, ranging from solar and electric vehicles (EVs) through to hydrogen and “new-energy” storage.

The plan also emphasises China’s willingness to steer climate governance and be seen as a provider of “global public goods”, in the form of affordable clean-energy technologies.

However, while the document says it will “promote the peaking” of coal and oil use, it does not set out a timeline and continues to call for the “clean and efficient” use of coal.

This shows that tensions remain between China’s climate goals and its focus on energy security, leading some analysts to raise concerns about its carbon-cutting ambition.

Below, Carbon Brief outlines the key climate change and energy aspects of the plan, including targets for carbon intensity, non-fossil energy and forestry.

Note: this article is based on a draft published on 5 March and will be updated if any significant changes are made in the final version of the plan, due to be released at the close next week of the “two sessions” meeting taking place in Beijing.

- What is China’s 15th five-year plan?

- What does the plan say about China’s climate action?

- What is China’s new CO2 intensity target?

- Does the plan encourage further clean-energy additions?

- What does the plan signal about coal?

- How will China approach global climate governance in the next five years?

- What else does the plan cover?

What is China’s 15th five-year plan?

Five-year plans are one of the most important documents in China’s political system.

Addressing everything from economic strategy to climate policy, they outline the planned direction for China’s socio-economic development in a five-year period. The 15th five-year plan covers 2026-30.

These plans include several “main goals”. These are largely quantitative indicators that are seen as particularly important to achieve and which provide a foundation for subsequent policies during the five-year period.

The table below outlines some of the key “main goals” from the draft 15th five-year plan.

| Category | Indicator | Indicator in 2025 | Target by 2030 | Cumulative target over 2026-2030 | Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic development | Gross domestic product (GDP) growth (%) | 5 | Maintained within a reasonable range and proposed annually as appropriate. | Anticipatory | |

| ‘Green and low-carbon | Reduction in CO2 emissions per unit of GDP (%) | 17.7 | 17 | Binding | |

| Share of non-fossil energy in total energy consumption (%) | 21.7 | 25 | Binding | ||

| Security guarantee | Comprehensive energy production capacity (100m tonnes of standard coal equivalent) |

51.3 | 58 | Binding |

Select list of targets highlighted in the “main goals” section of the draft 15th five-year plan. Source: Draft 15th five-year plan.

Since the 12th five-year plan, covering 2011-2015, these “main goals” have included energy intensity and carbon intensity as two of five key indicators for “green ecology”.

The previous five-year plan, which ran from 2021-2025, introduced the idea of an absolute “cap” on carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, although it did not provide an explicit figure in the document. This has been subsequently addressed by a policy on the “dual-control of carbon” issued in 2024.

The latest plan removes the energy-intensity goal and elevates the carbon-intensity goal, but does not set an absolute cap on emissions (see below).

It covers the years until 2030, before which China has pledged to peak its carbon emissions. (Analysis for Carbon Brief found that emissions have been “flat or falling” since March 2024.)

The plans are released at the two sessions, an annual gathering of the National People’s Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC). This year, it runs from 4-12 March.

The plans are often relatively high-level, with subsequent topic-specific five-year plans providing more concrete policy guidance.

Policymakers at the National Energy Agency (NEA) have indicated that in the coming years they will release five sector-specific plans for 2026-2030, covering topics such as the “new energy system”, electricity and renewable energy.

There may also be specific five-year plans covering carbon emissions and environmental protection, as well as the coal and nuclear sectors, according to analysts.

Other documents published during the two sessions include an annual government work report, which outlines key targets and policies for the year ahead.

The gathering is attended by thousands of deputies – delegates from across central and local governments, as well as Chinese Communist party members, members of other political parties, academics, industry leaders and other prominent figures.

What does the plan say about China’s climate action?

Achieving China’s climate targets will remain a key driver of the country’s policies in the next five years, according to the draft 15th five-year plan.

It lists the “acceleration” of China’s energy transition as a “major achievement” in the 14th five-year plan period (2021-2025), noting especially how clean-power capacity had overtaken fossil fuels.

The draft says China will “actively and steadily advance and achieve carbon peaking”, with policymakers continuing to strike a balance between building a “green economy” and ensuring stability.

Climate and environment continues to receive its own chapter in the plan. However, the framing and content of this chapter has shifted subtly compared with previous editions, as shown in the table below. For example, unlike previous plans, the first section of this chapter focuses on China’s goal to peak emissions.

| 11th five-year plan (2006-2010) | 12th five-year plan (2011-2015) | 13th five-year plan (2016-2020) | 14th five-year plan (2021-2025) | 15th five-year plan (2026-2030) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chapter title | Part 6: Build a resource-efficient and environmentally-friendly society | Part 6: Green development, building a resource-efficient and environmentally friendly society | Part 10: Ecosystems and the environment | Part 11: Promote green development and facilitate the harmonious coexistence of people and nature | Part 13: Accelerating the comprehensive green transformation of economic and social development to build a beautiful China |

| Sections | Developing a circular economy | Actively respond to global climate change | Accelerate the development of functional zones | Improve the quality and stability of ecosystems | Actively and steadily advancing and achieving carbon peaking |

| Protecting and restoring natural ecosystems | Strengthen resource conservation and management | Promote economical and intensive resource use | Continue to improve environmental quality | Continuously improving environmental quality | |

| Strengthening environmental protection | Vigorously develop the circular economy | Step up comprehensive environmental governance | Accelerate the green transformation of the development model | Enhancing the diversity, stability, and sustainability of ecosystems | |

| Enhancing resource management | Strengthen environmental protection efforts | Intensify ecological conservation and restoration | Accelerating the formation of green production and lifestyles | ||

| Rational utilisation of marine and climate resources | Promoting ecological conservation and restoration | Respond to global climate change | |||

| Strengthen the development of water conservancy and disaster prevention and mitigation systems | Improve mechanisms for ensuring ecological security | ||||

| Develop green and environmentally-friendly industries |

Title and main sections of the climate and environment-focused chapters in the last five five-year plans. Source: China’s 11th, 12th, 13th, 14th and 15th five-year plans.

The climate and environment chapter in the latest plan calls for China to “balance [economic] development and emission reduction” and “ensure the timely achievement of carbon peak targets”.

Under the plan, China will “continue to pursue” its established direction and objectives on climate, Prof Li Zheng, dean of the Tsinghua University Institute of Climate Change and Sustainable Development (ICCSD), tells Carbon Brief.

What is China’s new CO2 intensity target?

In the lead-up to the release of the plan, analysts were keenly watching for signals around China’s adoption of a system for the “dual-control of carbon”.

This would combine the existing targets for carbon intensity – the CO2 emissions per unit of GDP – with a new cap on China’s total carbon emissions. This would mark a dramatic step for the country, which has never before set itself a binding cap on total emissions.

Policymakers had said last year that this framework would come into effect during the 15th five-year plan period, replacing the previous system for the “dual-control of energy”.

However, the draft 15th five-year plan does not offer further details on when or how both parts of the dual-control of carbon system will be implemented. Instead, it continues to focus on carbon intensity targets alone.

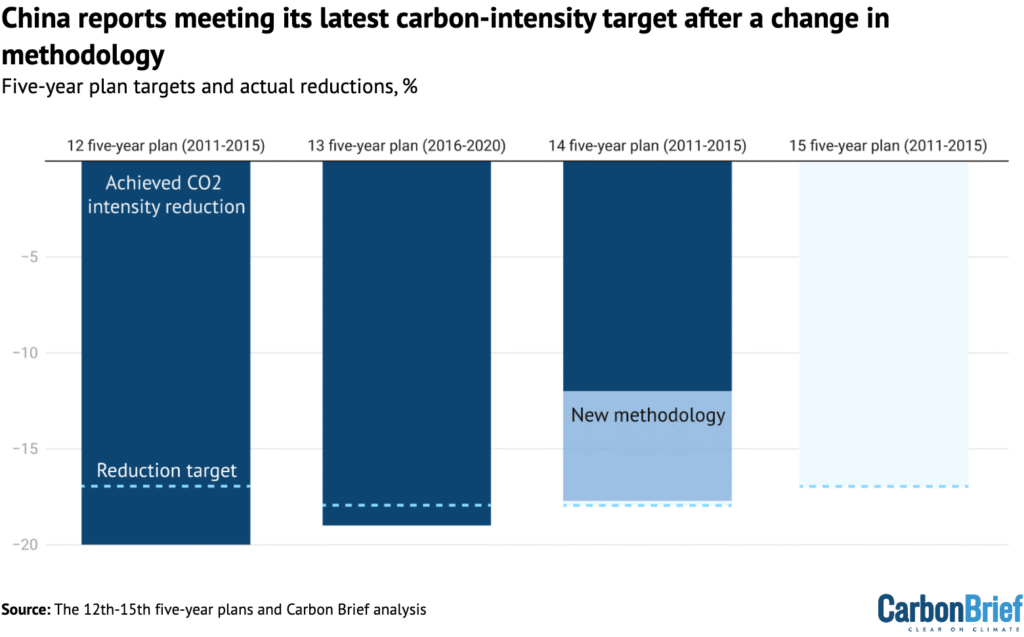

Looking back at the previous five-year plan period, the latest document says China had achieved a carbon-intensity reduction of 17.7%, just shy of its 18% goal.

This is in contrast with calculations by Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), which had suggested that China had only cut its carbon intensity by 12% over the past five years.

At the time it was set in 2021, the 18% target had been seen as achievable, with analysts telling Carbon Brief that they expected China to realise reductions of 20% or more.

However, the government had fallen behind on meeting the target.

Last year, ecology and environment minister Huang Runqiu attributed this to the Covid-19 pandemic, extreme weather and trade tensions. He said that China, nevertheless, remained “broadly” on track to meet its 2030 international climate pledge of reducing carbon intensity by more than 65% from 2005 levels.

Myllyvirta tells Carbon Brief that the newly reported figure showing a carbon-intensity reduction of 17.7% is likely due to an “opportunistic” methodological revision. The new methodology now includes industrial process emissions – such as cement and chemicals – as well as the energy sector.

(This is not the first time China has redefined a target, with regulators changing the methodology for energy intensity in 2023.)

For the next five years, the plan sets a target to reduce carbon intensity by 17%, slightly below the previous goal.

However, the change in methodology means that this leaves space for China’s overall emissions to rise by “3-6% over the next five years”, says Myllyvirta. In contrast, he adds that the original methodology would have required a 2% fall in absolute carbon emissions by 2030.

The dashed lines in the chart below show China’s targets for reducing carbon intensity during the 12th, 13th, 14th and 15th five-year periods, while the bars show what was achieved under the old (dark blue) and new (light blue) methodology.

The carbon-intensity target is the “clearest signal of Beijing’s climate ambition”, says Li Shuo, director at the Asia Society Policy Institute’s (ASPI) China climate hub.

It also links directly to China’s international pledge – made in 2021 – to cut its carbon intensity to more than 65% below 2005 levels by 2030.

To meet this pledge under the original carbon-intensity methodology, China would have needed to set a target of a 23% reduction within the 15th five-year plan period. However, the country’s more recent 2035 international climate pledge, released last year, did not include a carbon-intensity target.

As such, ASPI’s Li interprets the carbon-intensity target in the draft 15th five-year plan as a “quiet recalibration” that signals “how difficult the original 2030 goal has become”.

Furthermore, the 15th five-year plan does not set an absolute emissions cap.

This leaves “significant ambiguity” over China’s climate plans, says campaign group 350 in a press statement reacting to the draft plan. It explains:

“The plan was widely expected to mark a clearer transition from carbon-intensity targets toward absolute emissions reductions…[but instead] leaves significant ambiguity about how China will translate record renewable deployment into sustained emissions cuts.”

Myllyvirta tells Carbon Brief that this represents a “continuation” of the government’s focus on scaling up clean-energy supply while avoiding setting “strong measurable emission targets”.

He says that he would still expect to see absolute caps being set for power and industrial sectors covered by China’s emissions trading scheme (ETS). In addition, he thinks that an overall absolute emissions cap may still be published later in the five-year period.

Despite the fact that it has yet to be fully implemented, the switch from dual-control of energy to dual-control of carbon represents a “major policy evolution”, Ma Jun, director of the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE), tells Carbon Brief. He says that it will allow China to “provide more flexibility for renewable energy expansion while tightening the net on fossil-fuel reliance”.

Does the plan encourage further clean-energy additions?

“How quickly carbon intensity is reduced largely depends on how much renewable energy can be supplied,” says Yao Zhe, global policy advisor at Greenpeace East Asia, in a statement.

The five-year plan continues to call for China’s development of a “new energy system that is clean, low-carbon, safe and efficient” by 2030, with continued additions of “wind, solar, hydro and nuclear power”.

In line with China’s international pledge, it sets a target for raising the share of non-fossil energy in total energy consumption to 25% by 2030, up from just under 21.7% in 2025.

The development of “green factories” and “zero-carbon [industrial] parks” has been central to many local governments’ strategies for meeting the non-fossil energy target, according to industry news outlet BJX News. A call to build more of these zero-carbon industrial parks is listed in the five-year plan.

Prof Pan Jiahua, dean of Beijing University of Technology’s Institute of Ecological Civilization, tells Carbon Brief that expanding demand for clean energy through mechanisms such as “green factories” represents an increasingly “bottom-up” and “market-oriented” approach to the energy transition, which will leave “no place for fossil fuels”.

He adds that he is “very much sure that China’s zero-carbon process is being accelerated and fossil fuels are being driven out of the market”, pointing to the rapid adoption of EVs.

The plan says that China will aim to double “non-fossil energy” in 10 years – although it does not clarify whether this means their installed capacity or electricity generation, or what the exact starting year would be.

Research has shown that doubling wind and solar capacity in China between 2025-2035 would be “consistent” with aims to limit global warming to 2C.

While the language “certainly” pushes for greater additions of renewable energy, Yao tells Carbon Brief, it is too “opaque” to be a “direct indication” of the government’s plans for renewable additions.

She adds that “grid stability and healthy, orderly competition” is a higher priority for policymakers than guaranteeing a certain level of capacity additions.

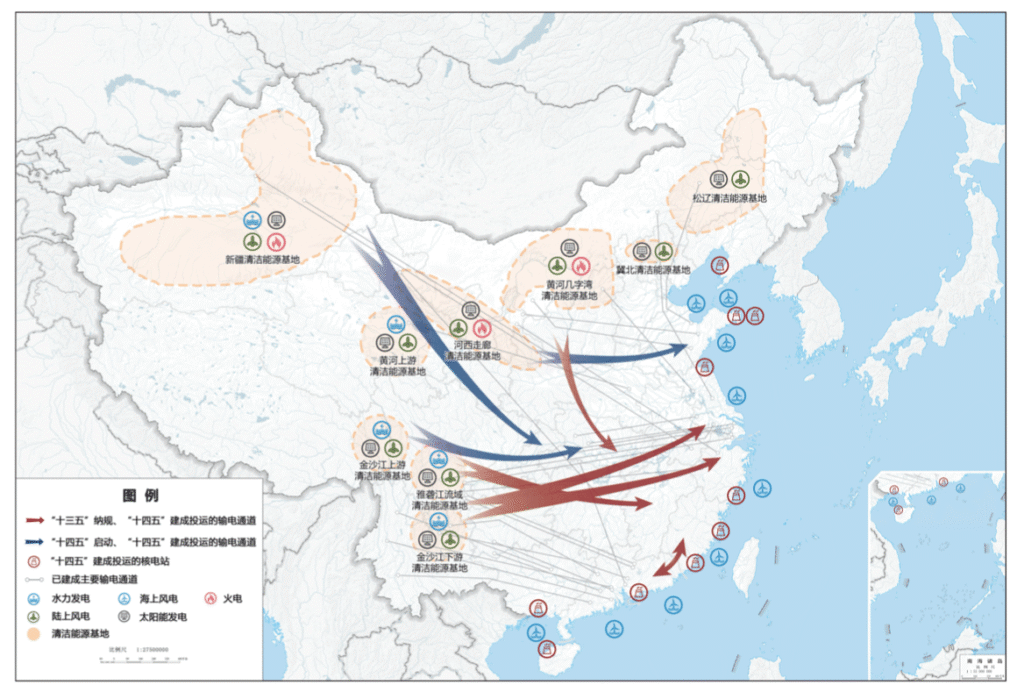

China continues to place emphasis on the need for large-scale clean-energy “bases” and cross-regional power transmission.

The plan says China must develop “clean-energy bases…in the three northern regions” and “integrated hydro-wind-solar complexes” in south-west China.

It specifically encourages construction of “large-scale wind and solar” power bases in desert regions “primarily” for cross-regional power transmission, as well as “major hydropower” projects, including the Yarlung Tsangpo dam in Tibet.

As such, the country should construct “power-transmission corridors” with the capacity to send 420 gigawatts (GW) of electricity from clean-energy bases in western provinces to energy-hungry eastern provinces by 2030, the plan says.

State Grid, China’s largest grid operator, plans to install “another 15 ultra-high voltage [UHV] transmission lines” by 2030, reports Reuters, up from the 45 UHV lines built by last year.

Below are two maps illustrating the interlinkages between clean-energy bases in China in the 15th (top) and 14th (bottom) five-year plan periods.

The yellow dotted areas represent clean energy bases, while the arrows represent cross-regional power transmission. The blue wind-turbine icons represent offshore windfarms and the red cooling tower icons represent coastal nuclear plants.

The 15th five-year plan map shows a consistent approach to the 2021-2025 period. As well as power being transmitted from west to east, China plans for more power to be sent to southern provinces from clean-energy bases in the north-west, while clean-energy bases in the north-east supply China’s eastern coast.

It also maps out “mutual assistance” schemes for power grids in neighbouring provinces.

Offshore wind power should reach 100GW by 2030, while nuclear power should rise to 110GW, according to the plan.

What does the plan signal about coal?

The increased emphasis on grid infrastructure in the draft 15th five-year plan reflects growing concerns from energy planning officials around ensuring China’s energy supply.

Ren Yuzhi, director of the NEA’s development and planning department, wrote ahead of the plan’s release that the “continuous expansion” of China’s energy system has “dramatically increased its complexity”.

He said the NEA felt there was an “urgent need” to enhance the “secure and reliable” replacement of fossil-fuel power with new energy sources, as well as to ensure the system’s “ability to absorb them”.

Meanwhile, broader concerns around energy security have heightened calls for coal capacity to remain in the system as a “ballast stone”.

The plan continues to support the “clean and efficient utilisation of fossil fuels” and does not mention either a cap or peaking timeline for coal consumption.

Xi had previously told fellow world leaders that China would “strictly control” coal-fired power and phase down coal consumption in the 15th five-year plan period.

The “geopolitical situation is increasing energy security concerns” at all levels of government, said the Institute for Global Decarbonization Progress in a note responding to the draft plan, adding that this was creating “uncertainty over coal reduction”.

Ahead of its publication, there were questions around whether the plan would set a peaking deadline for oil and coal. An article posted by state news agency Xinhua last month, examining recommendations for the plan from top policymakers, stated that coal consumption would plateau from “around 2027”, while oil would peak “around 2026”.

However, the plan does not lay out exact years by which the two fossil fuels should peak, only saying that China will “promote the peaking of coal and oil consumption”.

There are similarly no mentions of phasing out coal in general, in line with existing policy.

Nevertheless, there is a heavy emphasis on retrofitting coal-fired power plants. The plan calls for the establishment of “demonstration projects” for coal-plant retrofitting, such as through co-firing with biomass or “green ammonia”.

Such retrofitting could incentivise lower utilisation of coal plants – and thus lower emissions – if they are used to flexibly meet peaks in demand and to cover gaps in clean-energy output, instead of providing a steady and significant share of generation.

The plan also calls for officials to “fully implement low-carbon retrofitting projects for coal-chemical industries”, which have been a notable source of emissions growth in the past year.

However, the coal-chemicals sector will likely remain a key source of demand for China’s coal mining industry, with coal-to-oil and coal-to-gas bases listed as a “key area” for enhancing the country’s “security capabilities”.

Meanwhile, coal-fired boilers and industrial kilns in the paper industry, food processing and textiles should be replaced with “clean” alternatives to the equivalent of 30m tonnes of coal consumption per year, it says.

“China continues to scale up clean energy at an extraordinary pace, but the plan still avoids committing to strong measurable constraints on emissions or fossil fuel use”, says Joseph Dellatte, head of energy and climate studies at the Institut Montaigne. He adds:

“The logic remains supply-driven: deploy massive amounts of clean energy and assume emissions will eventually decline.”

How will China approach global climate governance in the next five years?

Meanwhile, clean-energy technologies continue to play a role in upgrading China’s economy, with several “new energy” sectors listed as key to its industrial policy.

Named sectors include smart EVs, “new solar cells”, new-energy storage, hydrogen and nuclear fusion energy.

“China’s clean-technology development – rather than traditional administrative climate controls – is increasingly becoming the primary driver of emissions reduction,” says ASPI’s Li. He adds that strengthening China’s clean-energy sectors means “more closely aligning Beijing’s economic ambitions with its climate objectives”.

Analysis for Carbon Brief shows that clean energy drove more than a third of China’s GDP growth in 2025, representing around 11% of China’s whole economy.

The continued support for these sectors in the draft five-year plan comes as the EU outlined its own measures intended to limit China’s hold on clean-energy industries, driven by accusations of “unfair competition” from Chinese firms.

China is unlikely to crack down on clean-tech production capacity, Dr Rebecca Nadin, director of the Centre for Geopolitics of Change at ODI Global, tells Carbon Brief. She says:

“Beijing is treating overcapacity in solar and smart EVs as a strategic choice, not a policy error…and is prepared to pour investment into these sectors to cement global market share, jobs and technological leverage.”

Dellatte echoes these comments, noting that it is “striking” that the plan “barely addresses the issue of industrial overcapacity in clean technologies”, with the focus firmly on “scaling production and deployment”.

At the same time, China is actively positioning itself to be a prominent voice in climate diplomacy and a champion of proactive climate action.

This is clear from the first line in a section on providing “global public goods”. It says:

“As a responsible major country, China will play a more active role in addressing global challenges such as climate change.”

The plan notes that China will “actively participate in and steer [引领] global climate governance”, in line with the principle of “common,but differentiated responsibilities”.

This echoes similar language from last year’s government work report, Yao tells Carbon Brief, demonstrating a “clear willingness” to guide global negotiations. But she notes that this “remains an aspiration that’s yet to be made concrete”. She adds:

“China has always favored collective leadership, so its vision of leadership is never a lone one.”

The country will “deepen south-south cooperation on climate change”, the plan says. In an earlier section on “opening up”, it also notes that China will explore “new avenues for collaboration in green development” with global partners as part of its “Belt and Road Initiative”.

China is “doubling down” on a narrative that it is a “responsible major power” and “champion of south-south climate cooperation”, Nadin says, such as by “presenting its clean‑tech exports and finance as global public goods”. She says:

“China will arrive at future COPs casting itself as the indispensable climate leader for the global south…even though its new five‑year plan still puts growth, energy security and coal ahead of faster emissions cuts at home.”

What else does the plan cover?

The impact of extreme weather – particularly floods – remains a key concern in the plan.

China must “refine” its climate adaptation framework and “enhance its resilience to climate change, particularly extreme-weather events”, it says.

China also aims to “strengthen construction of a national water network” over the next five years in order to help prevent floods and droughts.

An article published a few days before the plan in the state-run newspaper China Daily noted that, “as global warming intensifies, extreme weather events – including torrential rains, severe convective storms, and typhoons – have become more frequent, widespread and severe”.

The plan also touches on critical minerals used for low-carbon technologies. These will likely remain a geopolitical flashpoint, with China saying it will focus during the next five years on “intensifying” exploration and “establishing” a reserve for critical minerals. This reserve will focus on “scarce” energy minerals and critical minerals, as well as other “advantageous mineral resources”.

Dellatte says that this could mean the “competition in the energy transition will increasingly be about control over mineral supply chains”.

Other low-carbon policies listed in the five-year plan include expanding coverage of China’s mandatory carbon market and further developing its voluntary carbon market.

China will “strengthen monitoring and control” of non-CO2 greenhouse gases, the plan says, as well as implementing projects “targeting methane, nitrous oxide and hydrofluorocarbons” in sectors such as coal mining, agriculture and chemicals.

This will create “capacity” for reducing emissions by 30m tonnes of CO2 equivalent, it adds.

Meanwhile, China will develop rules for carbon footprint accounting and push for internationally recognised accounting standards.

It will enhance reform of power markets over the next five years and improve the trading mechanism for green electricity certificates.

It will also “promote” adoption of low-carbon lifestyles and decarbonisation of transport, as well as working to advance electrification of freight and shipping.

The post Q&A: What does China’s 15th ‘five-year plan’ mean for climate change? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: What does China’s 15th ‘five-year plan’ mean for climate change?

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Renewable Energy2 years ago

GAF Energy Completes Construction of Second Manufacturing Facility