Warming driven by deforestation caused an extra 28,000 heat-related deaths per year across Africa, South America and Asia over 2001-20, new research finds.

The study, published in Nature Climate Change, is the first to look at human health impacts of warming caused specifically by tropical deforestation, as opposed to the burning of fossil fuels, its lead author tells Carbon Brief.

The authors find that deforestation alone drove, on average, 0.45C of warming in the tropics over 2001-20, accounting for 64% of the total warming in regions with tropical forest loss.

They also find that tropical deforestation over 2001-20 exposed 345 million people to “local warming”, in addition to the warming they were already facing due to global warming.

Six out of every 100,000 people living in deforested areas died as a result of deforestation-induced warming during this time, they warn.

This number is higher in south-east Asia, with Vietnam setting a record of, on average, 29 deaths per 100,000 people.

A researcher who was not involved with the study tells Carbon Brief that the “sobering” paper “reframes tropical deforestation as not only a carbon emissions and ecological issue, but also a critical public health concern”.

Tropical deforestation

Tropical forests, mainly distributed across South America, Africa and Asia, account for 45% of global forest cover.

These regions are well-known for their high biodiversity and the crucial ecosystem services that they provide, such as carbon storage.

However, tropical forest loss is on the rise.

A record 6.7m hectares of previously intact tropical forest was lost last year, mainly due to fires and land clearing for agriculture. As the planet warms, worsening heat and drought extremes are also causing trees to become less resilient to change, resulting in forest degradation.

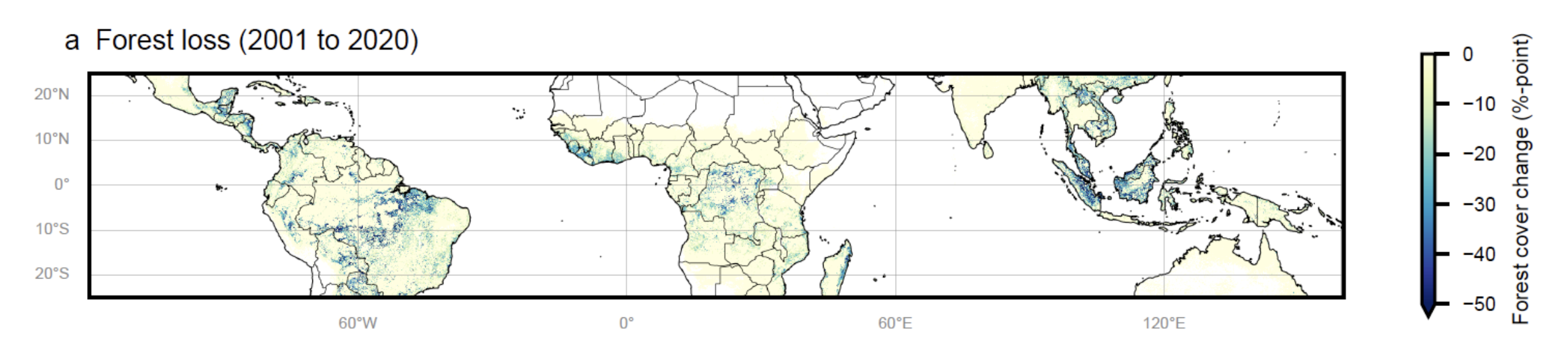

The new study uses data from the Global Land Analysis and Discovery laboratory at the University of Maryland to assess how tropical forest cover has changed year on year. The authors find that over 2001-20, a total of 1.6m square kilometres (160m hectares) of tropical forest was lost globally. This is shown on the map below, where blue indicates high forest loss and yellow indicates low loss.

The authors find the largest forest loss was in central and South America, but also highlight “extensive” loss in south-east Asia and tropical Africa.

Forest warming

Tropical deforestation has a wide range of negative consequences, including decreasing biodiversity, releasing carbon into the atmosphere and threatening the safety of Indigenous communities.

Loss of tree cover can also affect local temperatures by influencing the water cycle.

Water is constantly moving from the surface of the land into the atmosphere through a process called evapotranspiration. Plants play a crucial part in this process by moving water from the soil up through their roots and into their leaves, where it evaporates, cooling the air above. When trees are cut down, this cooling effect is reduced.

The authors use data of land surface temperatures from the NASA MODIS satellite to map warming in tropical regions over 2001-20. These results are shown in the map below, where red indicates warming and blue indicates cooling.

The authors find that between 2001-03 and 2018-20, surface temperatures increased by 0.34C in tropical central and South America, 0.1C in tropical Africa and 0.72C in south-east Asia. They add that “areas of forest loss coincide with areas of strong positive change in temperature across many regions of the tropics”.

By comparing their deforestation and surface warming maps, the authors find that deforested regions of the tropics saw an average of 0.7C warming over 2001-20, while areas that “maintained forest cover” saw an increase of only 0.2C.

By comparing the change in temperature in deforested regions with that in neighbouring locations without forest loss, they find that deforestation alone caused 0.45C of warming in the tropics over 2001-20 – accounting for 64% of total warming experienced over those regions.

Heat exposure

High temperatures can be deadly.

During periods of extreme heat, people can suffer from heat stroke and exhaustion – and even die. Those with underlying health conditions are at higher risk of fatal complications.

The authors use data from Oak Ridge National Laboratory’s LandScan to map where people live in the tropics. They estimate that 425 million people live in regions that were exposed to tropical deforestation over 2001-20, and just over three-quarters of them were exposed to warming as a result of the loss of forest cover.

Finally, the authors estimated “heat-related excess mortality” due to nearby tropical deforestation.

Using data from the 2019 Global Burden of Disease study, they determine the number of “non-accidental” deaths in each deforested tropical area. This excludes deaths from “external” causes, such as accidents and suicides, but includes “internal” causes, such as disease.

The researchers then used previously published “temperature-mortality” relationships for different countries. These relationships show the link between temperature and excess mortality rate, indicating the percentage increase in mortality for every degree of warming.

These relationships vary between countries, as people in hotter regions are generally better adapted to extreme heat.

By combining the data on local warming due to deforestation, temperature-mortality relationships and the non-accidental mortality data, the authors calculated how many non-accidental deaths would have been expected in deforested regions if they had not warmed due to the loss of forest cover.

By comparing the real and counterfactual mortality rates, the authors were able to calculate the total mortality burden due to tropical deforestation-induced warming.

Overall, the authors find that tropical deforestation drove an additional 28,300 deaths every year over 2001-20, accounting for 39% of the total heat-related mortality from global climate change and deforestation combined over locations of forest loss.

The study finds that, on average, six out of every 100,000 people living in deforested areas died as a result of deforestation-induced warming. However, these numbers vary by country.

The chart below shows the average annual deaths due to deforestation-induced heat per 100,000 people living in areas of forest loss.

Dr Carly Reddington is a research fellow at the University of Leeds and lead author of the study. She tells Carbon Brief that it is the “first study to look at human health impacts of tropical deforestation-induced warming”.

Dr Nicholas Wolff, a climate change scientist at the Nature Conservancy who was not involved with the study, tells Carbon Brief that the paper is “sobering”. He adds that it “reframes tropical deforestation as not only a carbon emissions and ecological issue, but also a critical public health concern”.

Data-scarce

The authors note that there are no country-specific heat vulnerability indices available for African countries. To develop their data for African countries, they used the average heat vulnerability index for South America.

Reddington tells Carbon Brief that Africa is the most “uncertain region” in the study and tells Carbon Brief that “more data is really crucial” to develop more accurate estimates.

Wolff tells Carbon Brief that extrapolating heat-mortality relationships “from data-rich regions to data-poor ones” is a “common practice in global-scale climate-health research”.

He praises the overall methodology as “innovative, transparent and scientifically sound, with appropriate caveats”.

Dr Luke Parsons, a climate modelling scientist at the Nature Conservancy, tells Carbon Brief that the conclusions are “robust”. However, he notes some “methodological issues” with the paper, such as the fact that all results are modelled, rather than measured.

He tells Carbon Brief that future work could assess “near-surface air temperature and humidity changes associated with deforestation, as well as study regional air temperature changes beyond deforested areas”.

While the new study focuses on warming within one square kilometre of forest loss, Reddington tells Carbon Brief that “deforestation is associated with warming up to 100km away”.

Furthermore, the study notes that the increase in deaths due to excess heat is likely to affect the most vulnerable members of society the most. It says:

“Vulnerable populations, particularly traditional and Indigenous communities, often live near deforested areas and face limited access to resources and infrastructure needed to cope with the combination of rising temperatures and environmental changes caused by deforestation and climate change.”

Wolff also stresses this disparity, adding that “many of these communities depend on forest clearing for agriculture, income and survival, and are forced to make difficult choices between short-term economic needs and long-term health and environmental stability”.

The authors also note that deforestation can drive a range of other interacting health problems, which were not considered in this study. For example, deforestation is linked to a rise in zoonotic diseases, such as malaria.

Dr Vikki Thompson, a climate scientist at the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute who was not involved in the study, says that the findings of the paper are “relevant to everyone”. She continues:

“We can reduce impacts of extreme heat by planting more trees and reducing deforestation everywhere, on both local and international scales.”

The post Warming due to tropical deforestation linked to 28,000 ‘excess’ deaths per year appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Warming due to tropical deforestation linked to 28,000 ‘excess’ deaths per year

Climate Change

The Farming Industry Has Embraced ‘Precision Agriculture’ and AI, but Critics Question Its Environmental Benefits

Why have tech heavyweights, including Google and Microsoft, become so deeply integrated in agriculture? And who benefits from their involvement?

Picture an American farm in your mind.

Climate Change

With Love: Living consciously in nature

I fell flat on my backside one afternoon this January and, weirdly, it made me think of you. Okay, I know that takes a bit of unpacking—so let me go back and start at the beginning.

For the last six years, our family has joined with half a dozen others to spend a week or so up at Wangat Lodge, located on a 50-acre subtropical rainforest property around three hours north of Sydney. The accommodation is pretty basic, with no wifi coverage—so time in Wangat really revolves around the bush. You live by the rhythm of the sun and the rain, with the days punctuated by swimming in the river and walking through the forest.

An intrinsic part of Wangat is Dan, the owner and custodian of the place, and the guide on our walks. He talks about time, place, and care with great enthusiasm, but always tenderly and never with sanctimony. “There is no such thing as ‘the same walk’”, is one of Dan’s refrains, because the way he sees it “every day, there is change in the world around you” of plants, animals, water and weather. Dan speaks of Wangat with such evident love, but not covetousness; it is a lightness which includes gentle consciousness that his own obligations arise only because of the historic dispossession of others. He inspires because of how he is.

One of the highlights this year was a river walk with Dan, during which we paddled or waded through most of the route, with only occasional scrambles up the bank. Sometimes the only sensible option is to swim. Among the life around us, we notice large numbers of tadpoles in the water, which is clean enough to drink. Our own tadpoles, the kids in the group, delight in the expedition. I overhear one of the youngest children declaring that she’s having ‘one of the best days ever’. Dan looks content. Part of his mission is to reintroduce children to nature, so that the soles of their feet may learn from the uneven ground, and their muscles from the cool of the water.

These moments are for thankfulness in the life that lives.

It is at the very end of the walk when I overbalance and fall on my arse—and am reminded of the eternal truth that rocks are hard. As I gingerly get up, my youngest daughter looks at me, caught between amusement and concern, and asks me if I’m okay.

I have to think before answering, because yes, physically I’m fine. But I feel too, an underlying sense of discomfort; it is that omnipresent pressure of existential awareness about the scale of suffering and ecological damage now at large in the world, made so much more immediately acute after Bondi; the dissonance that such horrors can somehow exist simultaneously with this small group being alive and happy in this place, on this earth-kissed afternoon.

How is it okay, to be “okay”? What is it to live with conscience in Wangat? Those of us who still have access to time, space, safety and high levels of volition on this planet carry this duality all the time, as our gift and obligation. It is not an easy thing to make sense of; but for me, it speaks to the question of ‘why Greenpeace’? Because the moral and strategic mission-focus of campaigning provides a principled basis for how each of us can bridge that interminable gulf.

The essence of campaigning is to make the world’s state of crisis legible and actionable, by isolating systemic threats to which we can rise and respond credibly, with resources allocated to activity in accordance with strategy. To be part of Greenpeace, whether as an activist, volunteer supporter or staff member, is to find a home for your worries for the world in confidence and faith that together we have the power to do something about it. Together we meet the confusion of the moment with the light of shared purpose and the confidence of direction.

So, it was as I was getting back up again from my tumble and considering my daughter’s question that I thought of you—with gratitude, and with love–-because we cross this bridge all the time, together, everyday; to face the present and the future.

‘Yes, my love’, I say to my daughter, smiling as I get to my feet, “I’m okay”. And I close my eyes and think of a world in which the fires are out, and everywhere, all tadpoles have the conditions of flourishing to be able to grow peacefully into frogs.

Thank you for being a part of Greenpeace.

With love,

David

Climate Change

Without Weighing Costs to Public Health, EPA Rolls Back Air Pollution Standards for Coal Plants

The federal Mercury and Air Toxics Standards for coal and oil-fired power plants were strengthened during the Biden administration.

Last week, when the Environmental Protection Agency finalized its repeal of tightened 2024 air pollution standards for power plants, the agency claimed the rollback would save $670 million.

Without Weighing Costs to Public Health, EPA Rolls Back Air Pollution Standards for Coal Plants

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits