Rachel Kyte CMG was appointed the UK’s special representative for climate in October 2024.

She is professor of practice in climate policy at the University of Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government, as well as dean emerita at Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

Previously, Kyte was the UN secretary-general’s special representative for sustainable energy, the CEO of Sustainable Energy for All and a vice president and special envoy for climate change at the World Bank.

- On her priorities for the role: “It’s really finance, forests and the energy transition externally.”

- On fraught geopolitics: “The Paris Agreement has worked; it just hasn’t worked well enough.”

- On the Paris Agreement: “It’s better than anything else we could negotiate today.”

- On the global response to Trump: “The rest of the world is like, ‘we’re growing, we need to grow, the fastest energy is renewable, how do we get our hands on it?’”

- On keeping 1.5C “alive”: “1.5C is still alive. 1.5C is not in good health.”

- On net-zero: “[T]he whole concept of net-zero is under attack from different political factions in a number of different countries. It is not isolated to one or two countries.”

- On climate pledges from key countries: “Let’s not make a fetish out of under-promising.”

- On delivering these pledges: “The conversations that I am engaged in…are like: ‘There’s no question about the direction of travel. The question is about the pace at which it can be executed.’”

- On COP30 outcomes: “The UK is engaged extensively with Brazil on a…potential large nature-finance package.”

- On climate impacts: “[W]e’ve got to deal with issues of adaptation, because [climate change is] happening right now, right here, right everywhere.”

- On fossil-fuel phaseout: “I think there are lots of informal discussions…around [whether] there [is] something [that] can be done on fossil-fuel subsidies.”

- On the climate-finance gap: “The pressure on our public resources is to make sure that that is targeted at where it can have the most impact.”

- On being an “activist shareholder”: “[T]he UK, which is such a significant shareholder across the multilateral development bank system…we have to be an activist shareholder.”

- On COP reform: “Should there be…summits every two years? People are talking about that.”

- On finance and the global south: “I’m not Pollyanna about this, but people [have] got really big problems in front of them.”

- On calls to slow action: “[W]hat I think we’re very forceful about is that you can’t take two to three years out of climate conferences just because the world’s really difficult.”

- On the impact of US tariffs: “[T]he sort of tariff era we’re in, the risk is that it slows down the investment in the clean-energy transition at a time when it needs to speed up.”

- On China’s role in the absence of the US: “They already were a major player. The world had already shifted in that direction.”

- On her climate “epiphany”: “I remember some very, very, strange meeting somewhere in eastern Europe and watching a really badly made movie about migration.”

Listen to this interview:

Carbon Brief: You were appointed the UK special representative for climate last October, a role that’s been held by the likes of John Ashton, David King and Nick Bridge over the last 15 years or so, and was left unfilled towards the tailend of the last government. Please, can you just explain what the role is and what your priorities are for it?

Rachel Kyte: So, it’s good to talk to you, nice to be here. So, the Labour government decided to appoint two envoys. They are politically appointed, so that does distinguish it a little bit from the past and so we are not civil servants; we occupy this space in support of ministers and in support of the civil service. So I’m the climate envoy and Ruth Davis is the nature envoy. I report to the foreign secretary [David Lammy] and the secretary of state for net-zero [Ed Miliband], and Ruth reports to the foreign secretary and to the secretary for Defra [Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs] [Steven Reed].

And our role is to help ministers project British climate and nature priorities in our engagements in the world. So we are externally focused, outside of the UK, and I think that Ruth and I coming in, and in discussion with ministers in the first weeks that we were here, focused in on the energy transition internationally, which is the extension of the energy mission domestically. Really progress around forest protection [and] tropical forest protection, because this is obviously on the critical path to getting to net-zero and, with COP30 coming up, and, having COP in the forest, this seemed to be an urgent policy. And then, for me, finance. And, of course, there’s climate finance, which is what gets negotiated in the COPs. And then there’s the financing of climate, which engages in a wider cross-Whitehall conversation around how we are building [the City of] London as the green financial centre [and] how we are exploiting the fact that the green economy is growing faster than the economy [overall].

So, inward trade investment, but outward trade investment. How we are mobilising private-sector finance. So, it’s really finance, forests and the energy transition externally.

You can imagine that the foreign secretary has a world that has got an awful lot more complicated in recent years. We’ve got more wars than we’ve had. We’ve got more grade-four famines. It’s a very, very complicated world.

So I think the envoys are there to try to support the prioritisation of climate and nature at the heart of foreign policy, which is what [the foreign secretary] said in his Kew speech. But then helping the service of the [Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office] deliver that externally.

CB: Thanks, Rachel. You nicely segued into our next question. We can definitely all agree that geopolitics is pretty fraught at the moment, perhaps more so than any time for decades. Multilateralism is under extreme pressure. We’ve seen that through recent UN summits, not just the COP. How does international climate policymaking – and, in particular, the Paris Agreement – survive this period of turbulence in your view? And, from some actors, there’s obviously outright hostility coming from some angles.

RK: So, it’s a great question. At the core of all of that is the fact that the Paris Agreement has worked; it just hasn’t worked well enough. And so how do we keep the conceit of the Paris Agreement? Which is that countries would have their nationally determined contributions, and that that ambition would filter up, and then when you put a wrap around it, you’ve got something that is on a line to net-zero by the middle of the century.

If countries start to slow down, or if countries start to walk away from that, how does the Paris Agreement still live? And we’re in that moment now.

But I think we have to hold two truths in our minds at the same time [within] a lot of climate, energy, nature policy. So, on the one hand, there is a direct attack; the United States has decided to leave the Paris Agreement. And I think there are many other countries looking for clarity from the United States about whether it will leave the underlying convention [the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change] as well. We don’t know.

But when I travel around the world, not withstanding that and notwithstanding some of the transactional interactions of the United States with other countries on a whole range of issues, the rest of the world is like, “well, we need to grow, we need to grow fast, we need fast energy, in particular”, right? Because I think countries really are worried that if they can’t get the energy security that they need that it becomes difficult for them to manage their economies and meet their people’s needs, but they’re also very worried about missing out on the AI [artificial intelligence] revolution.

So everybody wants a data centre, everybody wants to have enough energy for AI. But I think many emerging markets and developing economies are really worried that if they miss this next S-curve this would be defining for them for the next step. So the rest of the world is like, “we’re growing, we need to grow green, the fastest energy is renewable, how do we get our hands on it?”

At the same time, obviously, we still haven’t peaked emissions from fossil fuels. There’s a short-term economy, which is alive and well and funding into gas, etc. And we have two world views about what the future of the energy transition is. We have a US view, which is that climate change…what seems to be being articulated now is “climate change is real, but it’s just not a priority for us right now and we’re doubling down on the fossil-fuel economy”.

And then kind of the rest of the world, which is, like, “yeah, we are in transition, maybe we need to slow the transition, because the world is insecure and unstable”, but, at the end of the day, they can only meet their goals with access to more clean energy.

So I’ve reduced it down to energy, but you can have that conversation on a number of other aspects. So, yes, we have to keep the Paris Agreement as the place where we move forward from. It’s better than anything else we could negotiate today. And I think that it, therefore, does need to transform itself a little bit into a way of moving implementation forward and to move outside of the confines.

So, for example, we discuss resilience in the global economy, we discuss resilience in conflict, and we discuss resilience in development and, in climate, we talk about adaptation finance. Those two things have different origins, but they are, at the end of the day, going to come together in the same sets of decisions that countries make. So, how do we move forward in that debate?

And then, in particular, for those countries that come to COPs every year and don’t get what they want and face the existential crisis, how does this continue to be meaningful for them? And I think we have to answer that question over the next couple of years.

CB: You mentioned the Paris Agreement. We’re almost 10 years on from that landmark moment. One of the central calls at that moment 10 years ago [was] “1.5C to stay alive”. Is 1.5C alive still?

RK: 1.5C is still alive. 1.5C is not in good health. And so there is an important moment that, between now and COP30 [in Brazil this November], and then coming out of COP30, we will receive the synthesis report from the UN based on all of the NDCs [nationally determined contributions]. And we will get a sense of what kind of critical condition 1.5C is in.

And then I think we have to, as an international community, work out how to address that, but also how to communicate that to the world’s publics. Because, obviously, the whole concept of net-zero is under attack from different political factions in a number of different countries. It is not isolated to one or two countries.

So, I think the question of how we communicate where we are in the transition, it has to be addressed once we see the synthesis report. But that also goes to what’s really important for the next few weeks for me and the British government, which is to still encourage those countries that have to file their NDCs to have NDCs which are stretch targets; realistic, but ambitious.

We’ve still got the EU to come in. Still got China to come in. There are a number of key economies that haven’t filed their NDCs yet, so we can sort of get very doom-laden about where we are, but there is an opportunity for a number of key blocs to still maintain the ability to be ambitious.

CB: What are you particularly looking for from, say, the EU or China, some of these key NDCs?

RK: Well, to not walk away from ambition. There are all kinds of factors that go into a country’s NDCs; the capability, the rates of economic growth, the politics and the different political cultures have a different approach to under-promising and over-delivering, versus over-promising and under-delivering.

And, while you can respect under-promising and over-delivering, the delivery is important at this particular moment with [the] Paris [Agreement] fragile. I would say that this is the moment to promise realistically, right? And I think that’s where British diplomacy is focused at the moment. Let’s not make a fetish out of under-promising.

CB: Do you think that message is landing?

RK: Yeah, I think people are…So, my impression is that no country in the world is not living in the world, right? So people are watching the tariff wars, but…this is complicated. What does this mean for us?

I was in Southeast Asia a few weeks ago. Every country is trying to get a deal with the US and understand whether things are stable, or whether they’re going to change. It has direct impacts on the flow of finance into the clean-energy infrastructure that needs to be built. It has a direct impact on the cost of capital, etc.

Every country is watching the broader geopolitics. Everybody’s watching people become distracted by other wars and conflicts. And, in the middle of that, you’ve got to plot your way through to growth, right? And then that growth has to be greener, because [of] the cost of clean air or the benefit of clean air, the benefit of jobs, etc. This is understood, but this is a particularly difficult environment in which to navigate.

And, in the middle of that, we’re asking countries to plot out how they’re going to get to where they are committed to being. And for countries that produce conditional NDCs – ie if the finance is there, then we can do this – both trade and finance and international cooperation have been disrupted over the last year.

So, NDCs are complicated things to produce at the moment, just like any other growth plan. And so the conversations that I am engaged in, the further east and south you go, are like: “There’s no question about the direction of travel. The question is about the pace at which it can be executed.”

CB: Looking ahead to COP30 in Brazil later this year, realistically, you’ve already talked about a lot of different tensions that we’re facing, So what kind of outcomes are you expecting? And what are you pushing for?

RK: The UK is engaged extensively with Brazil on a couple of things. One is, I would describe it as a potential large nature finance package, right? Carbon markets, we agreed Article 6. There’s technical work that’s going on. There’s a lot of Article 6.2 activity. We are leading the coalition with Singapore and Kenya on demand for voluntary carbon markets. The Brazilians are very interested in the interoperability of compliance markets. So a piece around really driving carbon markets forward, because that would be a new stream of revenue, much needed, right? And answers part of the climate-finance problems.

Secondly, is the TFFF, the tropical forest – I always get it wrong –Tropical Forest Forever Facility. This is a flagship initiative of the Brazilian government and, if we have a COP in the forest, then we should be able to make breakthroughs in how we address the need to have a flow of finance into tropical-forest countries.

So, we’re working extensively with the Brazilians and we’re waiting for them to come forward with the prospectus. And then the question is our contribution [to the TFFF], if we make one with others, and also our ability to help the Brazilians go, basically, on a road show, right? And get other private-asset owners and asset managers and others into this fund.

And then maybe other nature finance things to do. Remember that biodiversity COPs always talk about climate, climate COPs never talk about nature, so we can correct for that. So that would be one bucket.

Then there’s going to be, this will not be negotiated, but the Brazilians will produce, together with the Azerbaijanis, a Baku-to-Belém roadmap. This, hopefully, will demystify how we get from $300bn to $1.3tn, or whatever the number is, and start to talk about how we scale; the leverage of public money for private money. So this is issues of standardisation of different asset classes, new asset classes [and] new ways of issuing bonds. So all of the mechanics of international finance that can be mobilised. And I think this is not well understood in a COP. It might be well understood in the City [of London] or in Frankfurt or Wall Street, but maybe this roadmap can demystify it.

And then I think we’ve got to deal with issues of adaptation, because it’s happening right now, right here, right everywhere, and the questions of adaptation finance, which isn’t just about the “quantum”. It’s also about what kind of financing: the grants, the need for concessional [financing], where the private sector is really able to mobilise and also quality [finance], and it’s also the accessibility of that finance.

We’re seeing huge improvement in the performance of the Green Climate Fund. The multilateral climate funds are just emerging now into an era where they can start to really deliver at scale. And then we’ve got the reform of the MDBs [multilateral development banks], where we, I think, have to be a much more activist shareholder.

So, finance, forests, bigger package on nature. I mean, there’s a lot more that needs to be negotiated, but I think those would be things that we can do, not withstanding the geopolitics.

CB: I’m quite struck that almost all of those things that you talked about are outside of the formal [COP30] negotiations. What do you think is going to happen on something like carrying forward the fossil-fuel transition outcome from Dubai?

RK: So I think there’s two things going on, right? One is what can we negotiate in the current environment, with the current postures of different groupings and different countries, and getting moving on the action around tripling renewables, doubling efficiency and transitioning away [from fossil fuels] is very important.

So, what could that look like? I think there are lots of informal discussions at the moment between different groups and with the Brazilians around [whether] there [is] something [that] can be done on fossil-fuel subsidies? Can we set targets within that that would allow us to measure progress? What can we usefully agree on that, this year?

And, then, I think there [are] conversations around where does the stuff that’s happening outside of COP land in a negotiated text? Or how does it get referenced?

I think we’re waiting for clarity from the Brazilians about their approach to a “cover text” and things like this. And I think this is still in the air. But these things that could happen outside of the negotiated text, referenced appropriately, give life and meaning to some of the paragraphs that need to be negotiated.

CB: With many major donors, including the UK, cutting their own budgets, even as countries made this collective pledge to scale up climate finance that you referenced, there’s a lot of expectation now on institutions like the World Bank and the multilateral development banks. Are these institutions capable of filling this climate-finance gap? Or where else should developing countries be looking? You mentioned maybe some of the carbon-market kind of revenue-raising, potentially? But, just on the wider pressures they are now facing, as we already alluded to, the kind of pressure on those multilateral institutions…

RK: Yes. So, we’re now basically – across the OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] – with a lot of countries hovering at like 0.3% GDP for ODA [official development assistance]. So, first of all, the war on nature and the climate crisis are one and the same thing, [they] are the context within which all growth and development happens, right? So the pressure on our public resources is to make sure that that is targeted at where it can have the most impact, where it’s needed most, and targeted at where it can be, where it can leverage itself, right?

So, we can talk about how we use ODA to sort of reduce emissions. There are certain geographies where emissions need to be curbed in order for us to get to 1.5C and then how do we use the public money to leverage other resources to crowd in and end the destruction of tropical rainforest or the protection of mangroves. So you take your climate-critical path, and you look at your ODA and you say: “How do we apply this the most effectively?”

For a country like the UK, which is such a significant shareholder across the multilateral development bank system, then we have to be an activist shareholder. And, yes, the answer is that the MDBs could do more. First of all, they’re doing more now than they were a few years ago. And they could do even more.

If we look at the leverage rates of the MDBs, those could go up. And I think in the conversations around the $300bn at COP29 it was very clear, especially from the regional development banks, that they thought that they could do more. And I think that in some instruments and in some ways in which they work, they could do a lot more. So I think those leverage rates should be over $1 for certain facilities, etc.

We know a lot more about how to use guarantees. We know a lot more about how to leverage the private sector using MDBs. The classic example for us was taking the Climate Investment Funds (CIF), putting a bond structure around their performing portfolio, and then listing it in London [on the stock exchange] and raising $7bn [$500m, following clarification after the interview], which then goes back to the CIF to be reinvested. I think there’s just been recent stories about the Inter-American Development Bank [IADB], which has a set of performing assets in its portfolio of renewable energy that can be turned into an instrument that can be listed, that generates money, that goes back into IADB.

So I think this is learnt now and, because of the ODA cuts, this becomes very, very important. So I am confident that there is a “to-do list” and that to-do list has come out of MDB reform work. It’s come out of the G20, TF-CLIMA, it’s come out of the Brazilians last year. It’s come out of other work that other thinktanks and others have been doing. London just listed…the government just announced a sustainable debt work here in the UK. So, that to-do list is a kind of “known known”. Right now the question is implementing it and that will require political leadership, for sure. And the Brazilians have created a circle of climate ministers, sort of 30 climate ministers to lead that. And there is a coalition of finance ministers convened by the World Bank.

We know what we need to do and now we need to start working out how to do it. The other thing is that we have an investor taskforce that the Treasury and the Foreign Office and leaders from the private sector have set up. And that’s sort of crunching its way through the mechanics of some of these things. But I think, as they start to go to market, we should be able to invest.

And there are a couple of things where we haven’t really faced up to yet. So, first of all, the private sector is investing in resilience, a) because it’s losing money, so it’s backstopping. And, secondly, because it can see how the world is being impacted by climate change, they are investing in their resilience in changed circumstances. That is captured as a cost in most countries in their accounts. That is not seen as an investment.

And also, I think in most countries – and certainly in the UN – we have no way to capture that. So we don’t really capture how much the private sector is already investing in its ability to just continue to operate under current climate conditions.

CB: It’s been really interesting over this year so far to see the Brazilian presidency of COP30 and also conversations at the Bonn talks in June explicitly referencing this idea of COP reform. What reforms would you propose or support?

RK: So, there’s no fixed British position on this yet, right? But I think what’s being discussed is there’s a utility to walking up to a mountain and putting a flag on the mountain every year, right? But, actually, we’re sort of in a more undulating landscape of implementation, where we need to be working throughout the year, right?

So, should there be Rio Trio summits every two years? People are talking about that. I think you could argue backwards and forwards, right or wrong, on that. What happens between the COPs? How do you bring the external world into the COPs? How do you let subnational actors and voices be heard at the COPs? These are all live topics and I think we need to move forward on most of them.

And then are we getting to the point where only certain countries can host them because they’re so big? I don’t know. Do you have thematic meetings throughout the year? How do we better keep real-time track of progress? So the next time we do a stocktake, in the world of AI and other things, is there a better and easier way? And can we still make that more transparent?

It would be great if the public could look at a sort of traffic-light spreadsheet and [say], “OK, we’re on track and not on track”. So I think all of those [questions are being asked] and it poses real challenges to the UN, which itself is in a process of reform now, in part, as a response to the US’s sort of questioning of the efficacy of parts of the UN, but also, I think, because the world is significantly changing.

CB: In your role, you’ve been in meetings over recent months with counterparts in Indonesia, China, South Africa, etc. What have been, particularly for some of those key countries, what have been the specific points of conversation you’ve had with them? Is it all about finance, or other important ingredients to those discussions?

RK: No, I think the starting point is, well, a lot of it is about finance, but, it’s about investment. It’s about growth and investment, right? It’s green growth and investment. And then finance fits into that.

So it’s not the finer points of the way finance is described in the COP. It is huge demand for the technical capacity of the UK, whether it is sophisticated demand-side management in grids, or how we regulate and how we oversee our grids in this country. Or how we exited from coal. Or what we are planning on some other dimension of the energy transition, our technical capacity and civil nuclear management. The desire for UK Inc’s knowledge about how we do things on things that we have actually been successful in – and also lessons of failure as well, honestly. So, everybody is figuring out how to do this.

There’s a strong desire for a pragmatic UK that is capable of convening across traditional blocs. I think we are seen as having a relationship with Brussels, a relationship with the US, a dialogue with China, a new free-trade agreement with India and a dialogue with India, [as well as] relationships through the Commonwealth and directly with small island states and least developed countries. We are seen as someone that already has bridges in place [and] could help strengthen those bridges.

So, what’s really been striking to me is it isn’t a conversation about, “oh woe is us, what we’re going to do?” It’s a conversation like: “I have a 10% growth rate. I need to do this. I would like you to be investing more.” It’s that kind of conversation – and that’s whether I’m meeting the minister of energy, finance, mines, environment, whoever I’m meeting with, that’s kind of the focus.

So I’m not Pollyanna about this, but people have got really big problems in front of them and it’s about their economic growth and development. And it’s, how can we help? I think the other thing that’s really coming through is just the cost of the impacts already, every flood, every failed harvest, every pressure on a city. I mean, this is really, really, really now…you can’t escape it, every country’s in the middle of it, we’re in the middle of it, domestically. And how this gets addressed, I think it is a question for this COP and the next COP.

CB: Other than the prime minister [Keir Starmer] and also your bosses, Ed Miliband and David Lammy, you’re kind of one of the key “faces” on the international stage representing just how invested the current UK government is in this issue of climate change. How do you think the UK’s role in this is perceived by other countries, ranging from China and other climate vulnerables, to the likes of the EU and the US?

RK: So, I think my perception of the external view of us is that – and what we’ve been trying to project as well – is “don’t do as we say, do as we do”. That means that we need to do a lot of things building on [the progress we’ve already made]. And I think that the beginning of the inward investment, just in the last year, into the clean-energy economy here [in the UK], that’s upwards of £50bn. So we’re open for business.

There’s one thing to talk about the City as a green financial centre, which has happened because of the leadership of City leaders, but now there’s this dialogue between government and the City about how to make that even broader. And, of course, that would mean becoming the western world’s heart of the carbon markets, if Singapore is the heart of the sort of eastern world’s carbon markets. It would mean that London helps define what a good biodiversity credit looks like, what a standardised swap looks like. There’s so much more that could be done there and I think that that’s what people want from us, but it’s also what we are trying to be able to build ourselves up to offer.

I think people want us engaged in the dialogue. So there’s a strategic dialogue with China. You could say that the strategic dialogue between China, the UK and the EU is the sort of triangular underpinning, actually, of the strength of the Paris Agreement. And, of course, we’re just about to see the EU-China summit, which will be important.

Our dialogue with India is interesting, right? So India found itself in a very difficult position at the end of COP29. In our free-trade agreement and in our strategic partnership with India climate and energy is a big part of that conversation. That’s all about technical lessons, learning and investment in both directions.

And then with the EU, the EU/UK reset is in the rearview mirror now. So now we need to get into the negotiations around the proximity, or the alignment between the ETSs [emissions trading schemes] shared stances on other issues and then how we show up as the sort of “liberal west” in the COPs.

So, the world is changing. It’s flatter. The BRICS are more and more important. We have, I think, powerful relationships with a number of key countries within the BRICS and that is an object of foreign policy, as well. And so how do we as the UK build up our agility, our global sense of the world and our place in it, so that we can help everybody stay on track for the kind of results we need by the middle of the century.

But what I think we’re very forceful about is that you can’t take two to three years out of climate conferences just because the world’s really difficult. And that has to be argued domestically and it has to be argued with [our] international partners. We don’t have time to just sort of say, “Oh, well, we’ll come back to that”. We have to build it in now.

CB: Specifically around the damage that’s been caused by the current trade tensions caused by the US, how do you think that is directly impacting the kind of wider climate negotiations, but also just the push towards the transition? Is this a key stumbling block now?

RK: Investment flows when everybody feels confident, right? And it just begs a whole bunch of questions and I think that’s slowing down investment decision-making.

So, I don’t think it’s specifically anti-climate, or whatever. I think it’s, generically, like if I don’t know if the tariff is 10%, 20%, 25%, 56%, whatever, well, let me put it off till the next quarter to make that investment decision. And I think that that’s what we’re beginning to see. So that, for me, is the main [thing]…It’s the hesitancy that it puts in the mind of government, but also in the mind of investors and the private sector.

I mean, it’s a little bit too early to tell in terms of investment not going into the US and going elsewhere, or individual supply chains for individual pieces of the clean transition, but I think the main problem globally is just this hesitation.

I would have to say that other things, including, perhaps, the ability of NOAA [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] and the National Weather Service to continue to provide services to the Caribbean and Central America, that the impact of the cuts to USAid [US Agency for International Development] in certain geographies are profound. But, generally, the sort of tariff era we’re in, the risk is that it slows down the investment in the clean-energy transition at a time when it needs to speed up.

CB: With the US in retreat, is China now the most important country in the world when it comes to climate action? Can you give a sense of your recent conversations with your Chinese counterparts, both recently, but also how they might have changed over recent years?

RK: So China’s posture before…there is obviously a China-US dynamic, but aside from that dynamic, China’s posture has been that “we are multilateralists, we want multilateralism to thrive and we’re all in”, right? And they’ve repeated that in every possible forum and they’ve repeated that at the highest level, including in [Chinese president] Xi Jinping’s statements at the leaders summit hosted by the UN secretary-general [António Guterres] and [Brazil’s] President Lula. So they are in.

Are they taking up space that would have been occupied by the US before? Nature abhors a vacuum, so all kinds of people are coming in. And the world moves towards China because of the fact that, over the last 25 years, it’s emerged as dominant in the solar-energy supply chain, with all of the problems that that has brought as well.

And then, financially, because of the way in which the [UNFCCC] convention is framed, they are a developing country, so they quite rightly only want their contributions to be made voluntarily, but they are a major player, right?

They already were a major player. The world had already shifted in that direction. Our conversation with them is technical and collegial and, I think, really frank. And we hosted the ministry of environment [Huang Runqiu] here recently [and] met with both the secretary of state for energy and the secretary of state for environment, and I was just really struck at how wide-ranging the issues that they would like to discuss is, and just how sort of practical, pragmatic and how sort of sleeves rolled up it was. And I think that’s also what is observed in their relationship with the conversations they’re having at a technical level in Brussels.

So it’s a complicated, nuanced relationship across all issues of trade, security, investment and climate. But they’re living in a world where climate is going to disrupt their own economy, if they don’t build their resilience. And of course, China has its tentacles everywhere. So maintaining our ability to talk to China about these issues, notwithstanding all of the other tensions and difficulties and opportunities, is “sine qua non”, I think. So let’s see how they show up in Belém.

CB: Just the final question, which is a bit more of a personal question, which we like to ask this of our interviewees, what is your first moment of epiphany on climate change? Can you remember? Was it a book, a lecture, a documentary, a conversation, or a trip you went on? Can you remember where that penny really dropped and you thought, I need to work on this, professionally and hard?

RK: There were two. One was very early on in my career. I was working on international youth politics in Europe. And, at that time, the Iron Curtain was up – I’m that old [smiles] – and sulfuric acid would go up from power plants in the east and it would land in the west and destroy the forest in Norway. And the conversation was: “Well, do you have ever-higher limits on the Norwegian industry?” Or do you go to Poland and say: “Look, can we put scrubbers on your [power plants]?” And it was the interconnected [nature of all this].

And, of course, at that time, young people in both east and western Europe wanted to build a more benign presence of Europe in the world and we wanted to be united, right? Or wanted the wall to come down. And that was a question of peace and environment. And it was the environment movement that was at the heart of the peace movement. So that was [a moment of thinking], “so I want to work on this”.

And I remember some very, very, strange meeting somewhere in eastern Europe and watching a really badly made movie about migration and the idea that, if we didn’t cope with this [climate change], people would come in boats across, presumably the Mediterranean. And I was, like, this is a global problem.

The second thing was just before Paris [in 2015]. There were these sort of famous rumours about all these women that got together and worked together to try to help the Paris Agreement happen. And so I was in a meeting with a bunch of women and two leaders from emerging markets, developing economies – it was very juxtaposed, because I was, at that point, the vice president of the World Bank – and we were having a discussion about 1.5C and whether, did it make sense as a strategy. And I was like: “2C is going to be difficult enough, you want to negotiate 1.5C?” And then we sort of broke. And then the next morning, we reconvened and we were just reflecting on the day before’s conversations and they both said to me: “You can’t just throw these numbers around as if they’re points of negotiation, because, for my culture, the difference between 2C and 1.5C is existence or non-existence”. And that was important.

CB: OK, thank you very much, Rachel.

RK: Thank you.

The post The Carbon Brief Interview: UK climate envoy Rachel Kyte appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter.

Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Food inflation on the rise

DELUGE STRIKES FOOD: Extreme rainfall and flooding across the Mediterranean and north Africa has “battered the winter growing regions that feed Europe…threatening food price rises”, reported the Financial Times. Western France has “endured more than 36 days of continuous rain”, while farmers’ associations in Spain’s Andalusia estimate that “20% of all production has been lost”, it added. Policy expert David Barmes told the paper that the “latest storms were part of a wider pattern of climate shocks feeding into food price inflation”.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “Cropped” email newsletter. A fortnightly digest of food, land and nature news and views. Sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

NO BEEF: The UK’s beef farmers, meanwhile, “face a double blow” from climate change as “relentless rain forces them to keep cows indoors”, while last summer’s drought hit hay supplies, said another Financial Times article. At the same time, indoor growers in south England described a 60% increase in electricity standing charges as a “ticking timebomb” that could “force them to raise their prices or stop production, which will further fuel food price inflation”, wrote the Guardian.

‘TINDERBOX’ AND TARIFFS: A study, covered by the Guardian, warned that major extreme weather and other “shocks” could “spark social unrest and even food riots in the UK”. Experts cited “chronic” vulnerabilities, including climate change, low incomes, poor farming policy and “fragile” supply chains that have made the UK’s food system a “tinderbox”. A New York Times explainer noted that while trade could once guard against food supply shocks, barriers such as tariffs and export controls – which are being “increasingly” used by politicians – “can shut off that safety valve”.

El Niño looms

NEW ENSO INDEX: Researchers have developed a new index for calculating El Niño, the large-scale climate pattern that influences global weather and causes “billions in damages by bringing floods to some regions and drought to others”, reported CNN. It added that climate change is making it more difficult for scientists to observe El Niño patterns by warming up the entire ocean. The outlet said that with the new metric, “scientists can now see it earlier and our long-range weather forecasts will be improved for it.”

WARMING WARNING: Meanwhile, the US Climate Prediction Center announced that there is a 60% chance of the current La Niña conditions shifting towards a neutral state over the next few months, with an El Niño likely to follow in late spring, according to Reuters. The Vibes, a Malaysian news outlet, quoted a climate scientist saying: “If the El Niño does materialise, it could possibly push 2026 or 2027 as the warmest year on record, replacing 2024.”

CROP IMPACTS: Reuters noted that neutral conditions lead to “more stable weather and potentially better crop yields”. However, the newswire added, an El Niño state would mean “worsening drought conditions and issues for the next growing season” to Australia. El Niño also “typically brings a poor south-west monsoon to India, including droughts”, reported the Hindu’s Business Line. A 2024 guest post for Carbon Brief explained that El Niño is linked to crop failure in south-eastern Africa and south-east Asia.

News and views

- DAM-AG-ES: Several South Korean farmers filed a lawsuit against the country’s state-owned utility company, “seek[ing] financial compensation for climate-related agricultural damages”, reported United Press International. Meanwhile, a national climate change assessment for the Philippines found that the country “lost up to $219bn in agricultural damages from typhoons, floods and droughts” over 2000-10, according to Eco-Business.

- SCORCHED GRASS: South Africa’s Western Cape province is experiencing “one of the worst droughts in living memory”, which is “scorching grass and killing livestock”, said Reuters. The newswire wrote: “In 2015, a drought almost dried up the taps in the city; farmers say this one has been even more brutal than a decade ago.”

- NOUVELLE VEG: New guidelines published under France’s national food, nutrition and climate strategy “urged” citizens to “limit” their meat consumption, reported Euronews. The delayed strategy comes a month after the US government “upended decades of recommendations by touting consumption of red meat and full-fat dairy”, it noted.

- COURTING DISASTER: India’s top green court accepted the findings of a committee that “found no flaws” in greenlighting the Great Nicobar project that “will lead to the felling of a million trees” and translocating corals, reported Mongabay. The court found “no good ground to interfere”, despite “threats to a globally unique biodiversity hotspot” and Indigenous tribes at risk of displacement by the project, wrote Frontline.

- FISH FALLING: A new study found that fish biomass is “falling by 7.2% from as little as 0.1C of warming per decade”, noted the Guardian. While experts also pointed to the role of overfishing in marine life loss, marine ecologist and study lead author Dr Shahar Chaikin told the outlet: “Our research proves exactly what that biological cost [of warming] looks like underwater.”

- TOO HOT FOR COFFEE: According to new analysis by Climate Central, countries where coffee beans are grown “are becoming too hot to cultivate them”, reported the Guardian. The world’s top five coffee-growing countries faced “57 additional days of coffee-harming heat” annually because of climate change, it added.

Spotlight

Nature talks inch forward

This week, Carbon Brief covers the latest round of negotiations under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which occurred in Rome over 16-19 February.

The penultimate set of biodiversity negotiations before October’s Conference of the Parties ended in Rome last week, leaving plenty of unfinished business.

The CBD’s subsidiary body on implementation (SBI) met in the Italian capital for four days to discuss a range of issues, including biodiversity finance and reviewing progress towards the nature targets agreed under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

However, many of the major sticking points – particularly around finance – will have to wait until later this summer, leaving some observers worried about the capacity for delegates to get through a packed agenda at COP17.

The SBI, along with the subsidiary body on scientific, technical and technological advice (SBSTTA) will both meet in Nairobi, Kenya, later this summer for a final round of talks before COP17 kicks off in Yerevan, Armenia, on 19 October.

Money talks

Finance for nature has long been a sticking point at negotiations under the CBD.

Discussions on a new fund for biodiversity derailed biodiversity talks in Cali, Colombia, in autumn 2024, requiring resumed talks a few months later.

Despite this, finance was barely on the agenda at the SBI meetings in Rome. Delegates discussed three studies on the relationship between debt sustainability and implementation of nature plans, but the more substantive talks are set to take place at the next SBI meeting in Nairobi.

Several parties “highlighted concerns with the imbalance of work” on finance between these SBI talks and the next ones, reported Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

Lim Li Ching, senior researcher at Third World Network, noted that tensions around finance permeated every aspect of the talks. She told Carbon Brief:

“If you’re talking about the gender plan of action – if there’s little or no financial resources provided to actually put it into practice and implement it, then it’s [just] paper, right? Same with the reporting requirements and obligations.”

Monitoring and reporting

Closely linked to the issue of finance is the obligations of parties to report on their progress towards the goals and targets of the GBF.

Parties do so through the submission of national reports.

Several parties at the talks pointed to a lack of timely funding for driving delays in their reporting, according to ENB.

A note released by the CBD Secretariat in December said that no parties had submitted their national reports yet; by the time of the SBI meetings, only the EU had. It further noted that just 58 parties had submitted their national biodiversity plans, which were initially meant to be published by COP16, in October 2024.

Linda Krueger, director of biodiversity and infrastructure policy at the environmental not-for-profit Nature Conservancy, told Carbon Brief that despite the sparse submissions, parties are “very focused on the national report preparation”. She added:

“Everybody wants to be able to show that we’re on the path and that there still is a pathway to getting to 2030 that’s positive and largely in the right direction.”

Watch, read, listen

NET LOSS: Nigeria’s marine life is being “threatened” by “ghost gear” – nets and other fishing equipment discarded in the ocean – said Dialogue Earth.

COMEBACK CAUSALITY: A Vox long-read looked at whether Costa Rica’s “payments for ecosystem services” programme helped the country turn a corner on deforestation.

HOMEGROWN GOALS: A Straits Times podcast discussed whether import-dependent Singapore can afford to shelve its goal to produce 30% of its food locally by 2030.

‘RUSTING’ RIVERS: The Financial Times took a closer look at a “strange new force blighting the [Arctic] landscape”: rivers turning rust-orange due to global warming.

New science

- Lakes in the Congo Basin’s peatlands are releasing carbon that is thousands of years old | Nature Geoscience

- Natural non-forest ecosystems – such as grasslands and marshlands – were converted for agriculture at four times the rate of land with tree cover between 2005 and 2020 | Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- Around one-quarter of global tree-cover loss over 2001-22 was driven by cropland expansion, pastures and forest plantations for commodity production | Nature Food

In the diary

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean | Brasília

- 5 March: Nepal general elections

- 9-20 March: First part of the thirty-first session of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) | Kingston, Jamaica

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz.

Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

Greenhouse Gases

Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’

Rising temperatures across France since the mid-1970s is putting Tour de France competitors at “high risk”, according to new research.

The study, published in Scientific Reports, uses 50 years of climate data to calculate the potential heat stress that athletes have been exposed to across a dozen different locations during the world-famous cycling race.

The researchers find that both the severity and frequency of high-heat-stress events have increased across France over recent decades.

But, despite record-setting heatwaves in France, the heat-stress threshold for safe competition has rarely been breached in any particular city on the day the Tour passed through.

(This threshold was set out by cycling’s international governing body in 2024.)

However, the researchers add it is “only a question of time” until this occurs as average temperatures in France continue to rise.

The lead author of the study tells Carbon Brief that, while the race organisers have been fortunate to avoid major heat stress on race days so far, it will be “harder and harder to be lucky” as extreme heat becomes more common.

‘Iconic’

The Tour de France is one of the world’s most storied cycling races and the oldest of Europe’s three major multi-week cycling competitions, or Grand Tours.

Riders cover around 3,500 kilometres (km) of distance and gain up to nearly 55km of altitude over 21 stages, with only two or three rest days throughout the gruelling race.

The researchers selected the Tour de France because it is the “iconic bike race. It is the bike race of bike races,” says Dr Ivana Cvijanovic, a climate scientist at the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development, who led the new work.

Heat has become a growing problem for the competition in recent years.

In 2022, Alexis Vuillermoz, a French competitor, collapsed at the finish line of the Tour’s ninth stage, leaving in an ambulance and subsequently pulling out of the race entirely.

Two years later, British cyclist Sir Mark Cavendish vomited on his bike during the first stage of the race after struggling with the 36C heat.

The Tour also makes a good case study because it is almost entirely held during the month of July and, while the route itself changes, there are many cities and stages that are repeated from year to year, Cvijanovic adds.

‘Have to be lucky’

The study focuses on the 50-year span between 1974 and 2023.

The researchers select six locations across the country that have commonly hosted the Tour, from the mountain pass of Col du Tourmalet, in the French Pyrenees, to the city of Paris – where the race finishes, along the Champs-Élysées.

These sites represent a broad range of climatic zones: Alpe d’ Huez, Bourdeaux, Col du Tourmalet, Nîmes, Paris and Toulouse.

For each location, they use meteorological reanalysis data from ERA5 and radiant temperature data from ERA5-HEAT to calculate the “wet-bulb globe temperature” (WBGT) for multiple times of day across the month of July each year.

WBGT is a heat-stress index that takes into account temperature, humidity, wind speed and direct sunlight.

Although there is “no exact scientific consensus” on the best heat-stress index to use, WBGT is “one of the rare indicators that has been originally developed based on the actual human response to heat”, Cvijanovic explains.

It is also the one that the International Cycling Union (UCI) – the world governing body for sport cycling – uses to assess risk. A WBGT of 28C or higher is classified as “high risk” by the group.

WBGT is the “gold standard” for assessing heat stress, says Dr Jessica Murfree, director of the ACCESS Research Laboratory and assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Murfree, who was not involved in the new study, adds that the researchers are “doing the right things by conducting their science in alignment with the business practices that are already happening”.

The researchers find that across the 50-year time period, WBGT has been increasing across the entire country – albeit, at different rates. In the north-west of the country, WBGT has increased at an average rate of 0.1C per decade, while in the southern and eastern parts of the country, it has increased by more than 0.5C per decade.

The maps below show the maximum July WBGT for each decade of the analysis (rows) and for hourly increments of the late afternoon (columns). Lower temperatures are shown in lighter greens and yellows, while higher temperatures are shown in darker reds and purples.

Six Tour de France locations analysed in the study are shown as triangles on the maps (clockwise from top): Paris, Alpe d’ Huez, Nîmes, Toulouse, Col du Tourmalet and Bordeaux.

The maps show that the maximum WBGT temperature in the afternoon has surpassed 28C over almost the entire country in the last decade. The notable exceptions to this are the mountainous regions of the Alps and the Pyrenees.

The researchers also find that most of the country has crossed the 28C WBGT threshold – which they describe as “dangerous heat levels” – on at least one July day over the past decade. However, by looking at the WBGT on the day the Tour passed through any of these six locations, they find that the threshold has rarely been breached during the race itself.

For example, the research notes that, since 1974, Paris has seen a WBGT of 28C five times at 3pm in July – but that these events have “so far” not coincided with the cycling race.

The study states that it is “fortunate” that the Tour has so far avoided the worst of the heat-stress.

Cvijanovic says the organisers and competitors have been “lucky” to date. She adds:

“It has worked really well for them so far. But as the frequency of these [extreme heat] events is increasing, it will be harder and harder to be lucky.”

Dr Madeleine Orr, an assistant professor of sport ecology at the University of Toronto who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief that the paper was “really well done”, noting that its “methods are good [and its] approach was sound”. She adds:

“[The Tour has] had athletes complain about [the heat]. They’ve had athletes collapse – and still those aren’t the worst conditions. I think that that says a lot about what we consider safe. They’ve still been lucky to not see what unsafe looks like, despite [the heat] having already had impacts.”

Heat safety protocols

In 2024, the UCI set out its first-ever high temperature protocol – a set of guidelines for race organisers to assess athletes’ risk of heat stress.

The assessment places the potential risk into one of five categories based on the WBGT, ranging from very low to high risk.

The protocol then sets out suggested actions to take in the event of extreme heat, ranging from having athletes complete their warm-ups using ice vests and cold towels to increasing the number of support vehicles providing water and ice.

If the WBGT climbs above the 28C mark, the protocol suggests that organisers modify the start time of the stage, adapt the course to remove particularly hazardous sections – or even cancel the race entirely.

However, Orr notes that many other parts of the race, such as spectator comfort and equipment functioning, may have lower temperatures thresholds that are not accounted for in the protocol, but should also be considered.

Murfree points out that the study’s findings – and the heat protocol itself – are “really focused on adaptation, rather than mitigation”. While this is “to be expected”, she tells Carbon Brief:

“Moving to earlier start times or adjusting the route specifically to avoid these locations that score higher in heat stress doesn’t stop the heat stress. These aren’t climate preventative measures. That, I think, would be a much more difficult conversation to have in the research because of the Tour de France’s intimate relationship with fossil-fuel companies.”

The post Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 20 February 2026: EU’s ‘3C’ warning | Endangerment repeal’s impact on US emissions | ‘Tree invasion’ fuelled South America’s fires

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Preparing for 3C

NEW ALERT: The EU’s climate advisory board urged countries to prepare for 3C of global warming, reported the Guardian. The outlet quoted Maarten van Aalst, a member of the advisory board, saying that adapting to this future is a “daunting task, but, at the same time, quite a doable task”. The board recommended the creation of “climate risk assessments and investments in protective measures”.

‘INSUFFICIENT’ ACTION: EFE Verde added that the advisory board said that the EU’s adaptation efforts were so far “insufficient, fragmented and reactive” and “belated”. Climate impacts are expected to weaken the bloc’s productivity, put pressure on public budgets and increase security risks, it added.

UNDERWATER: Meanwhile, France faced “unprecedented” flooding this week, reported Le Monde. The flooding has inundated houses, streets and fields and forced the evacuation of around 2,000 people, according to the outlet. The Guardian quoted Monique Barbut, minister for the ecological transition, saying: “People who follow climate issues have been warning us for a long time that events like this will happen more often…In fact, tomorrow has arrived.”

IEA ‘erases’ climate

MISSING PRIORITY: The US has “succeeded” in removing climate change from the main priorities of the International Energy Agency (IEA) during a “tense ministerial meeting” in Paris, reported Politico. It noted that climate change is not listed among the agency’s priorities in the “chair’s summary” released at the end of the two-day summit.

US INTERVENTION: Bloomberg said the meeting marked the first time in nine years the IEA failed to release a communique setting out a unified position on issues – opting instead for the chair’s summary. This came after US energy secretary Chris Wright gave the organisation a one-year deadline to “scrap its support of goals to reduce energy emissions to net-zero” – or risk losing the US as a member, according to Reuters.

Around the world

- ISLAND OBJECTION: The US is pressuring Vanuatu to withdraw a draft resolution supporting an International Court of Justice ruling on climate change, according to Al Jazeera.

- GREENLAND HEAT: The Associated Press reported that Greenland’s capital Nuuk had its hottest January since records began 109 years ago.

- CHINA PRIORITIES: China’s Energy Administration set out its five energy priorities for 2026-2030, including developing a renewable energy plan, said International Energy Net.

- AMAZON REPRIEVE: Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has continued to fall into early 2026, extending a downward trend, according to the latest satellite data covered by Mongabay.

- GEZANI DESTRUCTION: Reuters reported the aftermath of the Gezani cyclone, which ripped through Madagascar last week, leaving 59 dead and more than 16,000 displaced people.

20cm

The average rise in global sea levels since 1901, according to a Carbon Brief guest post on the challenges in projecting future rises.

Latest climate research

- Wildfire smoke poses negative impacts on organisms and ecosystems, such as health impacts on air-breathing animals, changes in forests’ carbon storage and coral mortality | Global Ecology and Conservation

- As climate change warms Antarctica throughout the century, the Weddell Sea could see the growth of species such as krill and fish and remain habitable for Emperor penguins | Nature Climate Change

- About 97% of South American lakes have recorded “significant warming” over the past four decades and are expected to experience rising temperatures and more frequent heatwaves | Climatic Change

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

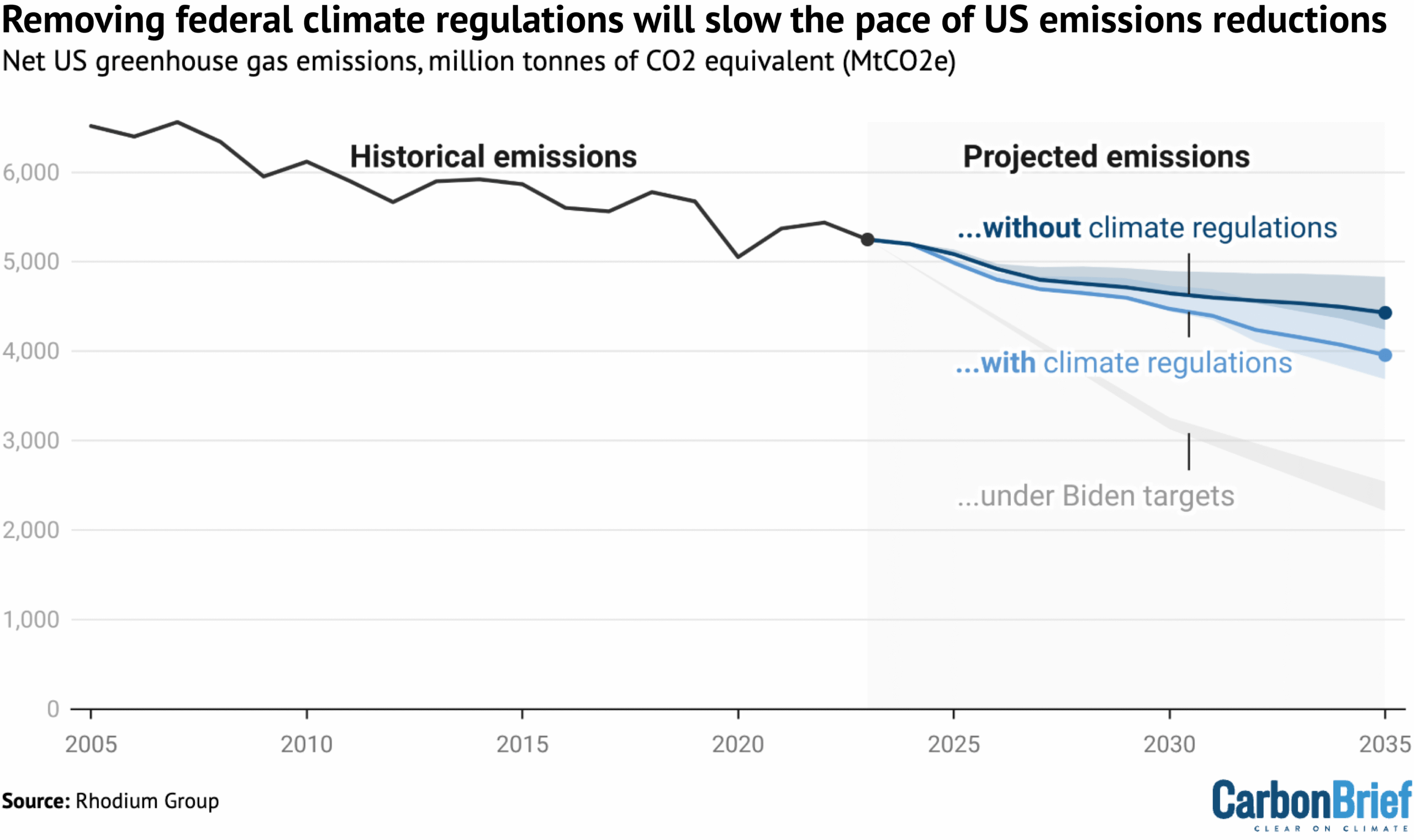

Repealing the US’s landmark “endangerment finding”, along with actions that rely on that finding, will slow the pace of US emissions cuts, according to Rhodium Group visualised by Carbon Brief. US president Donald Trump last week formally repealed the scientific finding that underpins federal regulations on greenhouse gas emissions, although the move is likely to face legal challenges. Data from the Rhodium Group, an independent research firm, shows that US emissions will drop more slowly without climate regulations. However, even with climate regulations, emissions are expected to drop much slower under Trump than under the previous Joe Biden administration, according to the analysis.

Spotlight

How a ‘tree invasion’ helped to fuel South America’s fires

This week, Carbon Brief explores how the “invasion” of non-native tree species helped to fan the flames of forest fires in Argentina and Chile earlier this year.

Since early January, Chile and Argentina have faced large-scale and deadly wildfires, including in Patagonia, which spans both countries.

These fires have been described as “some of the most significant and damaging in the region”, according to a World Weather Attribution (WWA) analysis covered by Carbon Brief.

In both countries, the fires destroyed vast areas of native forests and grasslands, displacing thousands of people. In Chile, the fires resulted in 23 deaths.

Multiple drivers contributed to the spread of the fires, including extended periods of high temperatures, low rainfall and abundant dry vegetation.

The WWA analysis concluded that human-caused climate change made these weather conditions at least three times more likely.

According to the researchers, another contributing factor was the invasion of non-native trees in the regions where the fires occurred.

The risk of non-native forests

In Argentina, the wildfires began on 6 January and persisted until the first week of February. They hit the city of Puerto Patriada and the Los Alerces and Lago Puelo national parks, in the Chubut province, as well as nearby regions.

In these areas, more than 45,000 hectares of native forests – such as Patagonian alerce tree, myrtle, coigüe and ñire – along with scrubland and grasslands, were consumed by the flames, according to the WWA study.

In Chile, forest fires occurred from 17 to 19 January in the Biobío, Ñuble and Araucanía regions.

The fires destroyed more than 40,000 hectares of forest and more than 20,000 hectares of non-native forest plantations, including eucalyptus and Monterey pine.

Dr Javier Grosfeld, a researcher at Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) in northern Patagonia, told Carbon Brief that these species, introduced to Patagonia for production purposes in the late 20th century, grow quickly and are highly flammable.

Because of this, their presence played a role in helping the fires to spread more quickly and grow larger.

However, that is no reason to “demonise” them, he stressed.

Forest management

For Grosfeld, the problem in northern Patagonia, Argentina, is a significant deficit in the management of forests and forest plantations.

This management should include pruning branches from their base and controlling the spread of non-native species, he added.

A similar situation is happening in Chile, where management of pine and eucalyptus plantations is not regulated. This means there are no “firebreaks” – gaps in vegetation – in place to prevent fire spread, Dr Gabriela Azócar, a researcher at the University of Chile’s Centre for Climate and Resilience Research (CR2), told Carbon Brief.

She noted that, although Mapuche Indigenous communities in central-south Chile are knowledgeable about native species and manage their forests, their insight and participation are not recognised in the country’s fire management and prevention policies.

Grosfeld stated:

“We are seeing the transformation of the Patagonian landscape from forest to scrubland in recent years. There is a lack of preventive forestry measures, as well as prevention and evacuation plans.”

Watch, read, listen

FUTURE FURNACE: A Guardian video explored the “unbearable experience of walking in a heatwave in the future”.

THE FUN SIDE: A Channel 4 News video covered a new wave of climate comedians who are using digital platforms such as TikTok to entertain and raise awareness.

ICE SECRETS: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast explored how scientists study ice cores to understand what the climate was like in ancient times and how to use them to inform climate projections.

Coming up

- 22-27 February: Ocean Sciences Meeting, Glasgow

- 24-26 February: Methane Mitigation Europe Summit 2026, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 25-27 February: World Sustainable Development Summit 2026, New Delhi, India

Pick of the jobs

- The Climate Reality Project, digital specialist | Salary: $60,000-$61,200. Location: Washington DC

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), science officer in the IPCC Working Group I Technical Support Unit | Salary: Unknown. Location: Gif-sur-Yvette, France

- Energy Transition Partnership, programme management intern | Salary: Unknown. Location: Bangkok, Thailand

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 20 February 2026: EU’s ‘3C’ warning | Endangerment repeal’s impact on US emissions | ‘Tree invasion’ fuelled South America’s fires appeared first on Carbon Brief.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits