Rapidly rising emissions from China’s agricultural machinery could “hinder” the country’s push to net-zero, according to new research.

The study, published in Nature Food, finds that carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from agricultural machinery have increased approximately seven-fold in the country since 1985.

Using government statistics on the quantity of farm equipment over time, researchers calculate the changes in CO2 emissions and other air pollutants between 1985 and 2020.

They find that CO2 emissions from farm equipment have grown, on average, by nearly 6% annually since 1985.

Based on “anticipated trends”, they say, increased mechanisation of agriculture could account for 21% of China’s total emissions in 2050, under a pathway to its 2060 net-zero goal.

This could make it harder for China to meet its emissions reduction goals, as well as “degrade” its air quality, the authors say.

However, the study also finds that widespread adoption of machinery powered with renewable energy could mitigate 65-70% of these emissions.

One expert, who was not involved in the research, tells Carbon Brief that the work is “valuable”, although she adds that farm machinery would likely not reach such a large proportion of total emissions:

“If China is making rapid progress in reducing emissions from other emitters…then I expect it will have made significant progress in the decarbonisation of agricultural machinery too.”

Machinery-related emissions

Food systems are responsible for around one-third of human-driven greenhouse gas emissions.

This figure includes everything associated with producing food – from the emissions caused by deforestation or other land-use changes to the methane belched by cows or off-gassed from manure.

In the new study, researchers rely on data from the China Statistical Yearbook, which provides annual statistics on a wide range of socioeconomic indicators. From the yearbook, the researchers use data on both the quantity and power of agricultural machinery in use in the country, as well as the properties of the fuel used in the machinery, cultivated land area, population and more.

In addition to CO2 emissions, the researchers calculate the machinery-related emissions of three types of air pollutants: fine particulate matter (PM2.5), nitrogen oxides (NOx) and total hydrocarbons (THC).

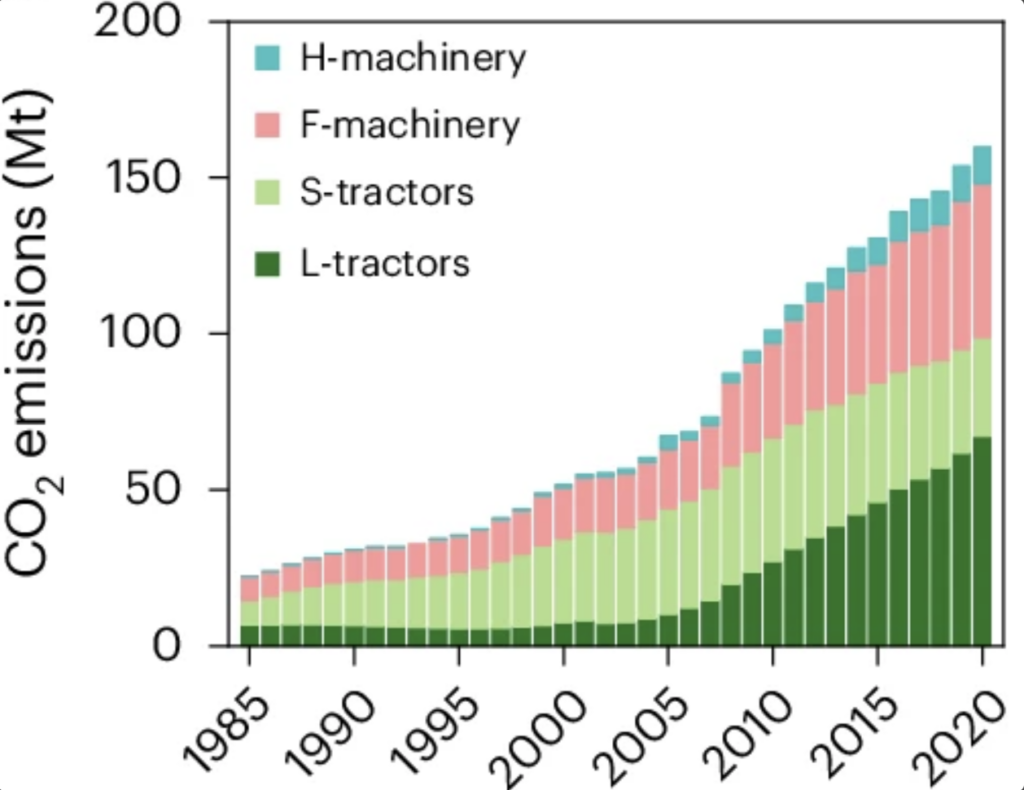

They divide the equipment into four categories: small tractors, large tractors, field-management machinery and harvest machinery. Then, they calculate the CO2, PM2.5, NOx and THC emissions for each type of machinery in each year.

The chart below shows the CO2 emissions for the study period of 1985 to 2020. The bars show emissions resulting from harvesting machinery (light blue), field-management machinery (pink), small tractors (light green) and large tractors (dark green).

They find that the total farm equipment CO2 emissions have increased from around 23m tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) in 1985 to nearly 160MtCO2 in 2020, growing annually by a rate of 5.7%.

This is equivalent to around 1.5% of the country’s total emissions in 2020. While this is only a small percentage, the amount of CO2 actually exceeds the annual emissions of entire countries – such as the Netherlands, the Philippines and Nigeria, the authors note.

In particular, the emissions contribution of large tractors has increased steadily since 2005. The authors attribute this to a “series of policies to promote large-scale machinery”.

Disaggregating the emissions of agricultural machinery from food systems more broadly “provides a unique perspective”, says Prof Zhangcai Qin, from Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, China. Qin, who was not involved in the new study, says that doing so “allow[s] policymakers to design targeted interventions without compromising agricultural productivity”.

Regional breakdown

The researchers also break the emissions down to the province level, finding a large range of agricultural machinery emissions – from 0.1MtCO2 for the lowest-emitting provinces to 17.5MtCO2 for the highest emitters.

They find that five provinces in eastern and north-eastern China – Shandong, Henan, Heilongjiang, Hebei and Anhui – account for more than 40% of agricultural machinery emissions. Together, those provinces contain one-third of the country’s cropland area and about 46% of the total engine power.

However, even between these high-emitting regions, the makeup of the machinery was different, with some provinces more dependent on large tractors and some more dominated by field-management machinery.

The sub-national emissions analysis is one of the key advances of the new research, says Dr Hannah Ritchie, deputy editor at Our World in Data. Ritchie, who was not involved in the study, explains:

“This spatial resolution of emissions estimates is valuable, because there is such large [variety] across a country of China’s size. It also offers important insights into potential emissions pathways in the future, under different rates of mechanisation and low-carbon technology uptake.”

Growth factors

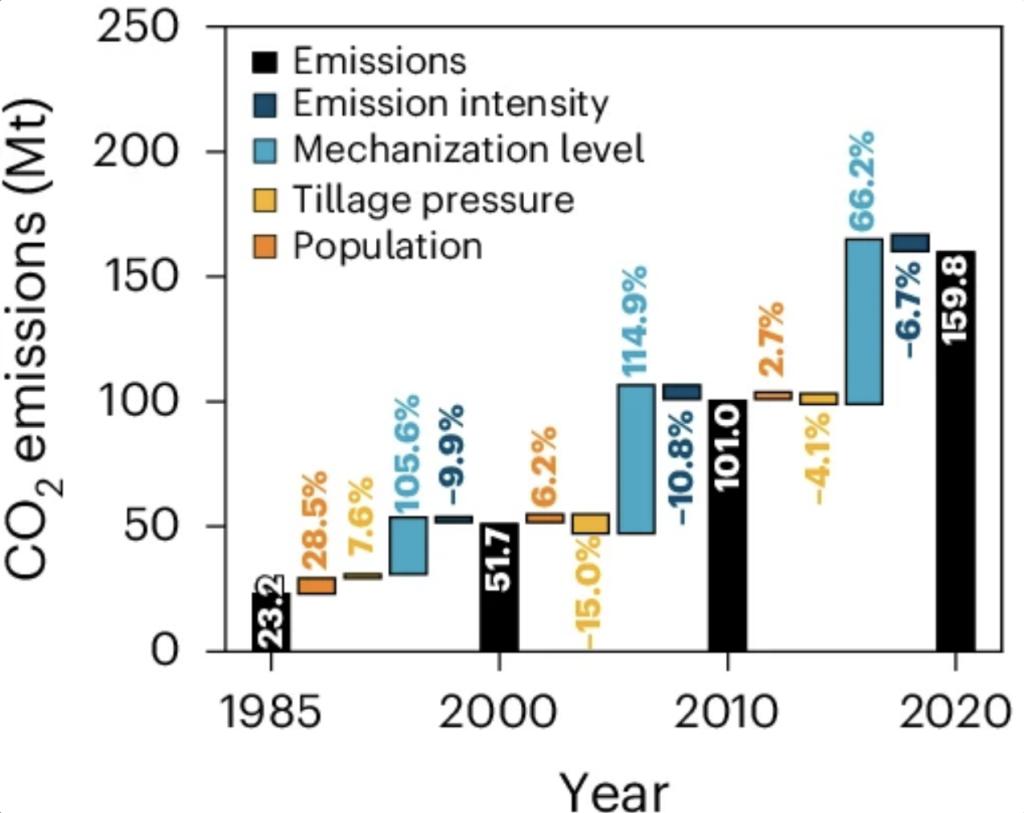

The researchers identify four socioeconomic factors contributing to the rise in emissions: population growth, changes in per-capita cropland area, level of mechanisation and emissions intensity.

The chart below shows the change in CO2 emissions (black) due to changes in emission intensity (dark blue), level of mechanisation (light blue), per-capita cropland area (yellow) and population (orange).

Of those, the increasing level of mechanisation “dominate[s]” the change in emissions, the paper says. It notes that these changes alone were responsible for around a 100% increase in emissions over 1985-2000.

Population growth was another large driver of increasing farm equipment emissions over the early part of the study period, the study notes, but it has been less of a factor since 2000.

In contrast, increasing emissions intensity uniformly acted to decrease emissions, the authors say, while “tillage pressure” increased emissions early on in the study period, but decreased emissions since 2000.

Carbon goals

Under current policies, China aims to “achieve comprehensive mechanisation in major crop production processes by 2035”, the authors note.

Therefore, unabated continued growth of agricultural mechanisation could compromise China’s efforts to achieve its “dual-carbon” goals, they warn.

(The term “dual-carbon” goals refers to the country’s pledge to reach peak CO2 emissions before 2030 and to achieve carbon neutrality before 2060.)

They write that effective mitigation of these emissions will require different strategies in the short- and long-term future, noting that near-term availability means that “biofuels and natural gas [will] play an important role over the coming decade”.

In the longer term, they say, renewable energy sources, as well as green hydrogen, “have the largest mitigation potential”. Previous work has shown that using automated equipment, electric tractors and renewable energy sources can reduce agricultural emissions by 90%.

Ritchie says she is “a bit sceptical that the relative contributions of agricultural machinery will be as high as 20% in 2050”. She adds:

“This rests on the assumption that these emissions go mostly unabated, while most other sectors rapidly decline. If China is making rapid progress in reducing emissions from other emitters, including larger on-road transport, such as trucks and other agricultural emissions…then I expect it will have made significant progress in the decarbonisation of agricultural machinery too.”

The post Rising emissions from farm equipment could ‘hinder’ China’s net-zero goals appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Rising emissions from farm equipment could ‘hinder’ China’s net-zero goals

Climate Change

Vanuatu pushes new UN resolution demanding full climate compensation

Countries responsible for climate change could be required to pay “full and prompt reparation” for the damage they have caused, under a new United Nations resolution being pursued by the Pacific island state of Vanuatu, an initial draft shows.

The resolution seeks to turn into action last year’s landmark advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which found that states have a legal obligation to prevent climate harm and that breaches of this duty could expose them to compensation claims from affected countries.

Under the “zero draft” of the resolution seen by Climate Home News, the UN’s General Assembly, its main policy-making body, would also demand that countries stop any “wrongful acts” contributing to rising emissions, which may include the production and licensing of planet-heating fossil fuels.

Gas flaring soars in Niger Delta post-Shell, afflicting communities

‘Demand’ is the strongest verb calling for an obligation to comply in UN language, but it is rarely used in a resolution.

Countries would also be called upon to respect their legal obligations by enacting national climate plans consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5C and by adopting appropriate policies, including measures to “ensure a rapid, just and quantified phase-out of fossil fuel production and use”, the document shows.

End of March vote targeted

The draft, meant as a starting point for negotiations, was circulated last week by the government of Vanuatu following discussions with a dozen nations, including the Netherlands, Colombia and Kenya.

Countries are expected to take part in informal consultations between February 13-17 aimed at agreeing on wording that would secure broad support among UN member states, according to a statement from Vanuatu, which also led the diplomatic drive for the ICJ’s advisory opinion. A vote on the follow-up resolution could take place by the end of March, it added.

Ralph Regenvanu, Vanuatu’s climate minister, said respecting the court’s decision is “essential for the credibility of the international system and for effective collective action”.

“At a time when respect for international law is under pressure globally, this initiative affirms the central role of the International Court of Justice and the importance of multilateral cooperation,” he added in written comments.

New damage register and reparation mechanism

If adopted in its current form, the draft resolution would also create an “International Register of Damage”, which is described as a comprehensive and transparent record of evidence on loss and damage linked to climate change.

It would also ask the UN secretary-general to put forward proposals for a climate reparation mechanism that could coordinate and facilitate the resolution of compensation claims and promote financial models to help cover climate-related damage.

The fledgling Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD) – set up under the UN climate change regime – is set to hand out money to the first set of initiatives aimed at addressing climate-driven destruction later this year. However, the just-over $590 million currently in the fund’s coffers is dwarfed by the scale of need in developing countries, with loss and damage costs estimated to reach up to $400 billion a year by 2030.

Like other small island nations, Vanuatu is among the world’s most vulnerable countries to the effects of climate change, while having contributed the least to global warming. Last year’s ICJ decision stemmed from a March 2023 resolution led by the Pacific nation asking the world’s top court to define countries’ legal obligations in relation to climate change.

Regenvanu said in September 2025 that it was important to follow up the ICJ ruling with a new UNGA resolution because it could be approved by a majority vote, while progress can be blocked in other fora like the UN climate negotiations that require consensus for decisions.

The post Vanuatu pushes new UN resolution demanding full climate compensation appeared first on Climate Home News.

Vanuatu pushes new UN resolution demanding full climate compensation

Climate Change

China maximises battery recycling to shore up critical mineral supplies

Even the busiest streets of Shanghai have become noticeably quieter as sales of electric vehicles (EVs) skyrocketed in China, with charging points mushrooming in residential compounds, car parks and service stations across the megacity.

Many Chinese drivers have upgraded their conventional vehicles to electric ones – or already replaced old EVs with newer models – incentivised by the government’s generous trade-in policies, or tempted by the latest hi-tech features such as controls powered by artificial intelligence (AI).

“Different from conventional cars, EVs are more like fast-moving consumer goods, like smartphones,” explained Mo Ke, founder and chief analyst of Tianjin-based battery-research firm, RealLi Research. Their digital systems can become outdated quickly, so Chinese people typically change their EVs after five or six years while a conventional car can be driven much longer, he told Climate Home News.

EV sales surpassed 16 million in China last year. Roughly 10% of all vehicles on the road were electric, and half of all new vehicles sold carried a green EV number plate, with an average of 45,000 EVs rolling off the production lines each day.

But while fast-growing EV uptake is good news for Chinese EV and battery manufacturers, it is creating a huge volume of spent batteries.

Tsunami of spent batteries

Last year, China generated nearly 400,000 tonnes of old or damaged power batteries, largely consisting of vehicle batteries, according to government data. That is projected to rise to one million tonnes per year in 2030, officials forecast.

The growing waste problem has spurred the government to launch a series of new policies aimed at regulating the country’s battery recycling industry, which though well-established is marked by a high degree of informality – especially in the lucrative repurposing sector where discarded EV batteries are given a new lease of life in less energy-intensive uses, such as power storage.

China is determined to build a “standardised, safe and efficient” recycling system for batteries, Wang Peng, a director at China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, told a press conference as the government launched a recycling industry push in mid-January.

A policy paper published by the government last month detailed Beijing’s plans to mandate end-of-life recycling for EVs together with their batteries to prevent them from entering the grey, informal market, and establish a digital system to track the lifecycle of every battery manufactured in the country. Under the plans, EV and battery makers will be held responsible for recycling the batteries they produce and sell.

“The volume of the Chinese market is too big, so it has to take actions ahead of other countries,” Mo said, adding that he expected the government to release more details about implementation of the plans in the near future.

Critical minerals choke point

China’s strategy for the battery recycling sector could also prove a boon for the world’s largest battery producer by bolstering its supply of minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel and manganese.

Along with the looming large-scale battery retirement, policymakers’ focus on battery recycling also reflects concern about critical minerals supplies, said Li Yifei, assistant professor of environmental studies at New York University Shanghai. “The government also felt the increasing pressure of securing resources,” he told Climate Home News.

“When you set up an efficient battery-recycling system, you essentially secure a new source for critical minerals, and that can help you enhance economic security. That’s why the industry is so important,” Lin Xiao, chief executive of Botree Recycling Technologies, a Chinese company offering battery-recycling solutions, told Climate Home News.

Cobalt and nickel-free electric car batteries boom in “good news” for rainforests

China dominates global refining of several minerals critical for producing EV batteries, but it still relies on imports of the raw materials – a choke point Beijing is acutely aware of, industry experts say.

China imports more than 90% of its cobalt, nickel and manganese, which are important ingredients for EV batteries, Hu Song, a senior researcher with the state-run China Automotive Technology and Research Centre, told China’s CCTV state broadcaster in June 2025. For lithium, the figure was around 60% in 2024, according to a separate report.

“If [those] resources cannot be recycled, then we will keep facing strangleholds in the future,” Hu said.

Big players gain ground

Spent EV batteries can be reused in settings that have lower energy requirements, such as in two-wheelers or energy-storage systems. When they become too depleted for repurposing, they can be scrapped and shredded into “black mass”, a powdery mixture containing valuable metals that can be recovered.

Reflecting the size of China’s EV market, the country already dominates global battery recycling capacity. It is home to 78% of the world’s battery pre-treatment capacity, which is for scrapping and shredding, and 89% of the capacity for refining black mass, according to 2025 forecasts by Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, a UK firm tracking battery supply chains.

A number of large corporate players have emerged in the sector in recent years.

Huayou Cobalt, a major producer of battery minerals, has built a business model for recycling, repurposing and shredding old batteries, as well as refining black mass and making new batteries using recovered materials.

It recently signed a deal with Encory, a joint venture between BMW and Berlin-based environmental service provider Interzero, to develop cutting-edge battery-recycling technologies, with their first joint factory set to open in China this year.

Suzhou-based Botree Recycling Technologies has developed various solutions to turn retired power batteries into new ones. Meanwhile, Brunp Recycling, the recycling arm of Chinese battery giant CATL, has built large factories to recycle lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries, a type of lithium battery that does not use nickel or cobalt, as well as nickel manganese cobalt (NMC) batteries, which are more popular outside of China.

But Mo, of RealLi Research, said much remains to be done to regulate and formalise the battery recycling industry.

Underground workshops

Across China, small underground workshops plague the repurposing sector, rebundling depleted batteries for sale without following industry standards or complying with health and safety requirements.

Because these operators have lower operational costs, they are able to offer higher prices to EV owners to buy their old batteries, undercutting formal recycling companies.

“This creates distortions in the market where legitimate players, who invest in proper detection, hazardous waste treatment and compliance, struggle to compete purely on price,” a spokesperson at CATL, the world’s largest battery manufacturer, told Climate Home News.

Despite such challenges, CATL’s Brunp subsidiary produced 17,100 tonnes of lithium in 2024 from the 128,700 tonnes of depleted batteries it recycled that year, according to CATL’s annual report.

Recycling expertise in demand

Since it was founded in 2019, Botree has formed partnerships with several major clients, which together recycle about half of China’s power batteries, the company’s CEO Lin said.

As other countries grapple with rising volumes of spent batteries, Chinese recyclers are also finding new foreign markets for their know-how.

Botree has joined forces with Spanish consulting firm ILUNION and renewable energy company EFT-Systems to build a factory to recycle LFP batteries in Valladolid.

The plant, scheduled to start operation in 2027, will be able to recycle 6,000 tonnes of LFPs annually when it opens, accounting for roughly 15% of demand in the Spanish market.

“(The companies) tell us what batteries they recycle and what battery materials they want to regenerate,” Lin said. “We can design a complete process for them.”

The post China maximises battery recycling to shore up critical mineral supplies appeared first on Climate Home News.

China maximises battery recycling to shore up critical mineral supplies

Climate Change

A Groundbreaking Geothermal Heating and Cooling Network Saves This Colorado College Money and Water

When a former oil and gas developer partnered with Colorado Mesa University on geothermal, the school saved millions and set a new standard for energy-efficient buildings.

GRAND JUNCTION, Colo.—The discussions started roughly a decade ago, when an account manager at Xcel Energy, the electricity and gas utility provider, expressed confusion, officials at Colorado Mesa University recalled.

A Groundbreaking Geothermal Heating and Cooling Network Saves This Colorado College Money and Water

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Renewable Energy2 years ago

GAF Energy Completes Construction of Second Manufacturing Facility