von Lena Westphal (Nachhaltigkeitsmanagement)

Immer häufiger stellt sich heraus, dass in vielen Bereichen im Leben keine Gleichberechtigung zwischen Frau und Mann besteht. Dies hat oft auch den Grund, dass die Forschung zu bestimmten Themen, die für Frauen relevant sind, rückschrittig ist bzw. sich gerade erst aufbaut. So ist bekannt, dass die Klimakrise mehr negative Auswirkungen auf Frauen als auf Männer hat. Der vierte Gleichstellungsbericht des Bundes greift dieses Thema als Fokusthema mit der Bezeichnung „Gleichstellung in der sozial-ökologischen Transformation“ auf.

Disclaimer: In diesem Blogartikel wird von dem Familienmodell Frau, Mann, evtl. Kind(er) gesprochen und sich auf ein binäres Geschlecht bezogen. Ich bin mir bewusst, dass es natürlich und zum Glück (!) viele verschiedene Familienmodelle und Geschlechter gibt und möchte darauf hinweisen, dass beispielsweise alleinstehende, alleinerziehende, Frauen mit einer Behinderung, Trans*frauen oder Frauen in einer gleichgeschlechtlichen Beziehung noch härter von den Auswirkungen der Klimakrise betroffen sind als heterosexuelle Cis-Frauen.

So nimmt die Marginalisierung von LGBTIQ+Personen beispielsweise im Katastrophenfall zu. Sie erfahren beim Zugang zu Wasser, Lebensmitteln, Gesundheitsversorgung und Notunterkünften häufig Diskriminierung.

*** English version below ***

Frauen sind gesundheitlich stärker von den Auswirkungen des Klimawandels betroffen als Männer, da sie häufiger mit Hitzesymptomen wie Kopfschmerzen, Leistungsabfall und Schlafstörungen zu kämpfen haben. Auch in der Schwangerschaft kann es durch Hitzewellen, die von der Erderwärmung ausgelöst werden, zu Komplikationen und sogar Frühgeburten kommen. Auch die Ressourcenverknappung, etwa bei Lebensmitteln, hat mehr Auswirkungen auf die Frau, da ihre Überlebenswahrscheinlichkeit geringer ist als bei Männern. So waren 2023 im Hitzesommer 75 Prozent aller Verstorbenen weiblich.

Es gibt auch gesellschaftliche und politische Gründe, warum Frauen stärker von der Erderwärmung betroffen sind. Das klassische Rollenbild einer Frau, das immer noch Teil unserer Gesellschaft ist, sieht vor, dass sich Frauen zunächst erstmal um andere kümmern und erst zum Schluss um sich selbst. Frauen leisten weltweit mehr Care-Arbeit (= Sorgearbeit oder Pflegearbeit) als Männer.

Die Ungleichverteilung von Sorge- und Haushaltsaufgaben erschwert es Frauen, sich an die Auswirkungen des Klimawandels anzupassen. So haben sie meistens einen schlecht bezahlten Job in der Familie und sind somit abhängig von ihrem Partner. Ihnen bleibt insgesamt auch weniger Zeit, sich ausreichend über den Klimawandel und dessen Folgen zu informieren.

Insgesamt sei betont, dass es sich hierbei nicht nur um Probleme der Frauen im globalen Süden handelt, sondern es ein weltweites Problem ist. Nach dem Wirbelsturm Katrina in den USA 2005 haben beispielsweise mehr Frauen als Männer aufgrund von Care-Arbeit ihren Job aufgegeben, damit sie sich besser um ihre Familien kümmern konnten.

Frauen arbeiten auch häufiger in Pflegeberufen und sind hier einem direkten Infektionsrisiko ausgesetzt, was die Corona-Pandemie bereits bestens gezeigt hat. Die Klimakrise wird langfristig für weitere und häufiger auftretende Pandemien sorgen und hier werden dann auch wieder Frauen einem erhöhten Infektionsrisiko ausgesetzt sein, da sie vermehrt an vorderster Front in systemrelevanten Berufen arbeiten. Pandemien sorgen zusätzlich dafür, dass die Gleichstellung von Frau und Mann wieder gefährdet wird, da sich Frauen auch eher um das Homeschooling der Kinder kümmern als Männer.

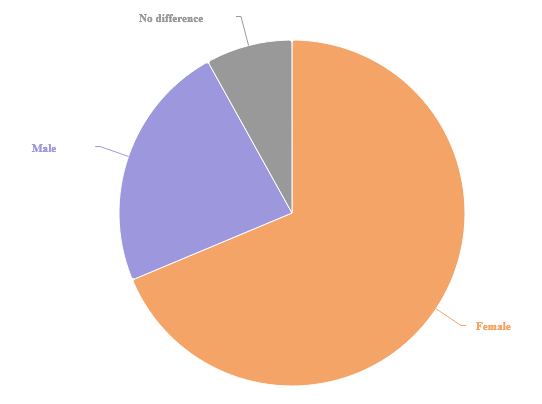

Mehr als zwei Drittel der Studien (68 Prozent) zeigen, dass Frauen durch den Klimawandel größeren Gesundheitsrisiken ausgesetzt sind. Das Kreisdiagramm zeigt die Ergebnisse von 130 Studien über Klimawandel und Gesundheit: 89 Studien kamen zu dem Ergebnis, dass Frauen stärker betroffen sind als Männer, 30 Studien kamen zu dem Ergebnis, dass Männer stärker betroffen sind als Frauen, und 11 Studien kamen zu dem Ergebnis, dass es keinen Unterschied in der Betroffenheit von Männern und Frauen gibt. Weltweit sind Frauen häufiger als Männer von klimabedingter Ernährungsunsicherheit betroffen und leiden nach extremen Wetterereignissen auch häufiger unter psychischen Erkrankungen oder Gewalt in der Partnerschaft.

Weltweit sind Frauen insgesamt stärker von Armut betroffen und verfügen über weniger Geld oder Besitz als Männer. Im globalen Süden haben Frauen tendenziell weniger Landbesitz, weniger Zugang zu landwirtschaftlichen Produktionsmitteln wie Geräten, Saatgut oder Dünger, aber auch weniger Kapital.

Aufgrund der zunehmenden Trockenheit verlängert sich die Strecke bis zu den Wasserquellen. Die Wasserversorgung ist in vielen Kulturen Frauensache und meistens essen und trinken Männer zuerst, sodass am Ende kaum noch etwas für die Frauen übrigbleibt, obwohl diese das Wasser, aufgrund ihrer Menstruation, dringend benötigen. Durch die weiteren Wege, machen sich die Frauen häufig schon im Dunkeln auf den Weg oder kehren erst nachts zurück, wodurch sie einem erhöhten Risiko von sexualisierter Gewalt ausgesetzt sind.

Frauen werden früher zu Hausarbeit, wozu auch das Heranschaffen von Wasser gehört, herangezogen. Sie haben dadurch weniger Zeit und Gelegenheit, Bildung zu erlangen, wenn die Wege zu den Wasserstellen immer weiter werden.

Die Lebensmittel werden aufgrund klimatischer Veränderungen insgesamt knapper. Frauen in ärmeren Ländern sind eher dem Risiko zu hungern ausgesetzt als Männer, da die knappe Nahrung eher an sie verteilt wird.

Auch politisch gesehen haben Frauen einen Nachteil. In selbstversorgenden Familien führt die Politik dazu, dass sich diese Familien auf immer schlechteren Böden durchschlagen müssen. Sobald Männer die Familien als “Klimaflüchtlinge” verlassen, müssen die hinterbliebenen Frauen ihre Familien alleine versorgen, was sie noch angreifbarer macht.

Kommt es zu Extremwetterereignissen verletzen sich oder sterben Frauen sogar häufiger als Männer. Vor allem in Ländern, in denen Frauen einen niedrigeren sozioökonomischen Status haben, gehen diese selten ohne männliche Begleitung aus dem Haus, tragen Kleidung, die die Bewegungsfreiheit bei möglichen Überflutungen sehr einschränkt und werden später vor Klimakatastrophen gewarnt. Während die Männer bei der Arbeit sind, kümmern sich Frauen zu Hause um die Familie und den Haushalt. Oft können Frauen auch nicht schwimmen, was die Flucht bei Überschwemmungen nahezu unmöglich macht. So waren 2004 bei dem Tsunami in Südostasien 70 Prozent der Todesopfer Frauen.

Als 1991 der Zyklon “Gorki” an der Küste von Bangladesch wütete, kamen neunmal mehr Frauen ums Leben als Männer. Bei den verheerenden Buschbränden 2009 in Australien wollten sich doppelt so viele Frauen als Männer in Sicherheit bringen. Und als 2016 in Kenia wegen einer schweren Dürre zwei Millionen Menschen hungern mussten, waren es jeweils die Frauen, die als letzte Lebensmittel erhielten.

Hinzu kommt, dass klimawandelbedingte Katastrophen häufig die Versorgung mit Mitteln der Familienplanung und den Zugang zu gynäkologischen Untersuchungen oder Geburtshilfe einschränken.

Als wäre das nicht alles schon genug, steigt auch die sexualisierte Gewalt gegenüber Frauen. Zwangsheiraten könnten im globalen Süden wieder zunehmen, weil die Klimakrise den Zugang zu Bildung und Hilfsangeboten stark negativ beeinflusst. Es kommt zu Ernteausfällen, junge Frauen werden vermehrt zu Hause gebraucht, um die Familien zu unterstützen und werden häufiger jung verheiratet oder gegen Vieh verkauft. Es kommt auch dazu, dass (junge) Frauen zu Prostitution gezwungen werden. Dies hat dazu geführt, dass im südlichen Afrika, aufgrund von Dürreperioden, die HIV-Infektionen gestiegen sind. All diese “Maßnahmen” werden von den Familien durchgeführt, um das fehlende Einkommen zu kompensieren und die restliche Familie vor Hunger zu schützen.

Selbst wenn Frauen in Notunterkünften unterkommen, sind sie dort vermehrt Gewaltdelikten ausgesetzt und haben nahezu keine Privatsphäre.

Gerade weil Frauen stärker vom Klimawandel betroffen sind, nehmen sie den Klimawandel stärker als Bedrohung wahr als Männer. Sie setzen sich mehr für den Klimaschutz ein und fordern auch mehr politische Maßnahmen und sind auch bereit, mehr Geld dafür auszugeben. So war es ab dem 20. August 2018 Greta Thunberg, die in Schweden die „Schulstreiks für’s Klima“ startete und damit weltweit die “Fridays For Future”-Bewegung loslöste.

In Deutschland ist vor allem Luisa Neubauer für ihren Aktivismus bekannt und setzt sich auf Demos oder in Talkrunden vor allem mit männlichen Politikern auseinander. Generell sind überproportional viele Frauen an der Protestbewegung beteiligt.

(Quelle: Utopia.de)

Frauen haben insgesamt einen klimafreundlicheren Lebensstil. Sie essen weniger Fleisch und fahren weniger Auto. Oft ist das aber keine bewusste Entscheidung, da sie weniger befugt sind, einen umweltbelastenden Lebensstil zu führen. Eine französische Studie fand vor kurzem heraus, dass Männer 26 Prozent mehr CO₂-Emissionen verursachen als Frauen. Während auf Männer jährlich 5,3 Tonnen CO₂ zurückgehen, sind es bei Frauen 3,9 Tonnen. Die Bereiche Verkehr und Ernährung machen zusammen rund die Hälfte eines durchschnittlichen CO₂-Fußabdruckes aus.

Viele argumentieren, dass Männer mehr Kalorien oder Fleisch benötigen oder allein durch ihren Job mehr CO₂ verbrauchen als Frauen. Dies konnte die Studie allerdings widerlegen. Rechnet man alle sozioökonomischen, biologischen und gesellschaftlichen Unterschiede heraus, bleibt immer noch ein Geschlechterunterschied von 18 Prozent. Für diese restlichen 18 Prozent konnten die Forscher:innen keine Erklärung bieten.

In Ländern, in denen Frauen politisch mehr Mitspracherecht haben, ist jedoch auch die CO₂-Belastung geringer und das Interesse an strukturellen Veränderungen größer. Außerdem zeigen Frauen in ihrem Alltag mehr Engagement, etwa beim Einkauf, bei der Arbeit, bei politischen Wahlen oder beim Engagement in ihren privaten Bereichen.

Leider ist es bisher weltweit so, dass kaum Frauen an den politischen Entscheidungen mitwirken können, da sie bei beispielsweise Klimakonferenzen immer noch unterrepräsentiert sind. Ihre Bedürfnisse werden von den männlichen Entscheidungsträgern stets vernachlässigt. Dementsprechend hätte es einen großen Einfluss, wenn Frauen mehr zu sagen hätten und häufiger bei Entscheidungen beteiligt werden.

Seit Jahrzehnten warnen Expert:innen, dass klassische Geschlechterrollen die Menschen anfälliger für extreme Wetterereignisse machen. Politische Entscheidungsträger haben diese Warnungen lange ignoriert. Heute sind sie gezwungen umzudenken und sich zu fragen, wie sich Ungleichheiten abbauen lassen, die sich anderenfalls immer weiter zu verstärken drohen.

Die Klimakrise bedroht vor allem arme Bevölkerungsschichten, die keinen politischen Einfluss haben. Die meisten Frauen haben kein Mitspracherecht, wenn es um die Diskussion um die Verwendung und Nutzung von Ressourcen oder um grundlegende Entscheidungen geht.

Im Pariser Klimaabkommen von 2015 haben sich die Staatsoberhaupte darauf geeinigt, die globale Erderwärmung auf durchschnittlich 1,5 Grad Celsius über dem vorindustriellen Niveau zu begrenzen. Die Unterzeichner:innen einigten sich zudem auch auf einen “geschlechtergerechten” Ansatz bei der Anpassung an den Klimawandel. Dieser sollte sich an den besten verfügbaren wissenschaftlichen Erkenntnissen orientieren.

Um dieses Ziel zu erreichen, müssten die Systeme verändert werden, die noch immer an alten Ungleichheiten festhalten. Machtverhältnisse müssen neu gedacht werden. Dies würde bedeuten, dass Reichtum und Ressourcen weltweit gleichmäßiger verteilt werden müssen und es eine gerechtere Mitbestimmung und Beteiligung bei umweltpolitischen Themen gibt.

Bisher gibt es allerdings wenig Belege für diesen Wandel, weshalb die Ungleichheit immer noch Tagesordnung ist. Die Beteiligung von Frauen an Anpassungsprojekten ist sehr selten und auch in der nationalen Klimapolitik werden die Bedürfnisse von Frauen nicht genug beachtet.

Die Geschlechtergleichheit wird aber immerhin in vielerlei Hinsicht angestrebt. So ist es beispielsweise eines der 17 Ziele der Sustainable Development Goals (kurz: SDG’s). Durch die UN-Klimakonferenzen gründeten sich auch zwei transnationale Netzwerke: das zivilgesellschaftliche GenderCC – Women for Climate Justice und die Global Gender and Climate Alliance (GGCA).

Abschließend muss jedoch betont werden, dass das persönliche Konsumverhalten von Frauen und Männern einen nicht so großen Einfluss auf das Klima hat wie Unternehmen. Rund 100 Unternehmen machen weltweit bereits 70 Prozent der Treibhausemissionen aus. Somit haben Politik und Wirtschaft den größeren Einfluss.

Außerdem gibt es auch Momente, in denen Männer stärker vom Klimawandel bedroht sind, als Frauen. Dies ist allerdings die Seltenheit. Ein Beispiel ist aber, dass Männer, aufgrund ihres klassischen Rollenbildes, bei Waldbränden länger in ihrem Haus bleiben, um es zu “beschützen”, während sich die Frauen mit dem restlichen Teil der Familie in Sicherheit bringen. Dies ist u. a. auf die toxische Männlichkeit zurückzuführen, aufgrund derer dieses Verhalten von Männern erwartet wird. Dieser Faktor ist natürlich auch nicht gesund. Allerdings ist bewiesen, dass der Klimawandel zu einseitig naturwissenschaftlich und damit stark stereotyp männlich diskutiert wird. Frauen leiden somit insgesamt mehr unter den Folgen der Klimakrise und viele dieser Folgen wurden durch patriarchle Strukturen verursacht.

*** English version ***

Climate crisis: women more affected than men

by Lena Westphal (Sustainability Management)

It is becoming increasingly apparent that in many areas of life there is no equality between women and men. This is often due to the fact that research on certain topics that are relevant to women is lagging behind or is only just beginning to develop. For example, it is known that the climate crisis has more negative effects on women than on men. The federal government’s fourth Gender Equality Report takes up this topic as a focus theme with the title “Equality in the socio-ecological transformation”.

Disclaimer: This blog article refers to the family model of woman, man, possibly child(ren) and refers to a binary gender. I am aware that there are of course and fortunately (!) many different family models and genders and would like to point out that, for example, single women, single parents, women with a disability, trans* women or women in a same-sex relationship are even harder hit by the effects of the climate crisis than heterosexual cis women.

For example, the marginalization of LGBTIQ+ people increases in the event of a disaster. They often experience discrimination when it comes to access to water, food, healthcare and emergency shelters.

Women’s health is more affected by the effects of climate change than men, as they are more likely to suffer from heat-related symptoms such as headaches, reduced performance and sleep disorders. Heatwaves caused by global warming can also lead to complications and even premature births during pregnancy. The scarcity of resources, such as food, also has a greater impact on women, as they are less likely to survive than men. In 2023, for example, 75 percent of all deaths in the heatwave summer were female.

There are also social and political reasons why women are more affected by global warming. The classic role model of a woman, which is still part of our society, is that women first take care of others and only then take care of themselves. Worldwide, women perform more care work than men.

The unequal distribution of care and household tasks makes it difficult for women to adapt to the effects of climate change. They usually have a low-paid job in the family and are therefore dependent on their partner. Overall, they also have less time to inform themselves sufficiently about climate change and its consequences.

Overall, it should be emphasized that this is not just a problem for women in the Global South, but a worldwide problem. After Hurricane Katrina in the USA in 2005, for example, more women than men gave up their jobs due to care work so that they could take better care of their families.

Women also work more frequently in care professions and are directly exposed to the risk of infection, as the coronavirus pandemic has already shown. The climate crisis will lead to further and more frequent pandemics in the long term, and women will again be exposed to an increased risk of infection, as they are increasingly working at the front line in systemically relevant professions. Pandemics also ensure that gender equality is once again at risk, as women are also more likely to homeschool their children than men.

More than two thirds of the studies (68 percent) show that women are exposed to greater health risks as a result of climate change. The pie chart shows the results of 130 studies on climate change and health: 89 studies came to the conclusion that women are more affected than men, 30 studies came to the conclusion that men are more affected than women, and 11 studies came to the conclusion that there is no difference in the extent to which men and women are affected. Globally, women are more likely than men to be affected by climate-related food insecurity and are also more likely to suffer from mental illness or intimate partner violence following extreme weather events.

Worldwide, women are generally more affected by poverty and have less money or property than men. In the global South, women tend to own less land, have less access to agricultural production resources such as equipment, seeds or fertilizer, but also less capital.

Due to the increasing drought, the distance to water sources is increasing. In many cultures, water supply is a matter for women and men usually eat and drink first, so that in the end there is hardly anything left for the women, even though they urgently need the water due to their menstruation. Due to the longer distances, women often set off in the dark or only return at night, which exposes them to an increased risk of sexualized violence.

Women are called upon to do housework earlier, including fetching water. As a result, they have less time and opportunity to gain an education as the distances to water points become ever longer.

Food is becoming scarcer overall due to climatic changes. Women in poorer countries are more at risk of starvation than men, as the scarce food is more likely to be distributed to them.

Women are also at a political disadvantage. In self-sufficient families, the policy means that these families have to eke out a living on increasingly poor soil. As soon as men leave their families as “climate refugees”, the women left behind have to support their families alone, which makes them even more vulnerable.

When extreme weather events occur, women are injured or even die more often than men. Particularly in countries where women have a lower socio-economic status, they rarely leave the house without a male companion, wear clothing that severely restricts their freedom of movement in the event of flooding and are later warned of climate disasters. While men are at work, women are at home taking care of the family and the household. Women often cannot swim either, which makes it almost impossible for them to escape in the event of flooding. In the 2004 tsunami in South East Asia, for example, 70 percent of the fatalities were women.

When Cyclone “Gorki” hit the coast of Bangladesh in 1991, nine times more women lost their lives than men. During the devastating bushfires in Australia in 2009, twice as many women tried to flee to safety as men. And when two million people went hungry due to a severe drought in Kenya in 2016, it was women who were the last to receive food.

In addition, climate change-related disasters often limit the supply of family planning resources and access to gynecological examinations or obstetric care.

As if that wasn’t enough, sexualized violence against women is also on the rise. Forced marriages could increase again in the Global South because the climate crisis is having a major negative impact on access to education and aid. There are crop failures, young women are increasingly needed at home to support their families and are more often married off young or sold for livestock. (Young) women are also forced into prostitution. This has led to an increase in HIV infections in southern Africa due to periods of drought. All these “measures” are carried out by families to compensate for the lack of income and to protect the rest of the family from hunger. Even if women are accommodated in emergency shelters, they are increasingly exposed to violence and have almost no privacy.

Precisely because women are more affected by climate change, they perceive climate change as more of a threat than men. They are more committed to climate protection and also demand more political measures and are prepared to spend more money on them. It was Greta Thunberg, for example, who launched the “School Strikes for the Climate” in Sweden on August 20, 2018, thereby triggering the “Fridays For Future” movement worldwide.

In Germany, Luisa Neubauer in particular is known for her activism and mainly confronts male politicians at demonstrations or in talks. In general, a disproportionately high number of women are involved in the protest movement.

(source: Utopia.de)

Overall, women have a more climate-friendly lifestyle. They eat less meat and drive less. However, this is often not a conscious decision, as they are less empowered to lead an environmentally harmful lifestyle. A French study recently found that men cause 26 percent more CO₂ emissions than women. While men are responsible for 5.3 tons of CO₂ per year, the figure for women is 3.9 tons. The transport and food sectors together account for around half of an average CO₂ footprint.

Many argue that men need more calories or meat or consume more CO₂ than women simply because of their job. However, the study was able to disprove this. If all socio-economic, biological and social differences are factored out, there is still a gender difference of 18 percent. The researchers were unable to provide an explanation for this remaining 18%.

However, in countries where women have a greater political say, carbon pollution is also lower and interest in structural change is greater. Women also show more commitment in their everyday lives, for example when shopping, at work, in political elections or in their private lives.

Unfortunately, women have hardly been able to participate in political decisions worldwide to date, as they are still underrepresented at climate conferences, for example. Their needs are always neglected by male decision-makers. Accordingly, it would have a major impact if women had more say and were more frequently involved in decision-making.

For decades, experts have warned that traditional gender roles make people more vulnerable to extreme weather events. Political decision-makers have long ignored these warnings. Today, they are forced to rethink and ask themselves how inequalities can be reduced, which otherwise threaten to become ever more pronounced.

The climate crisis primarily threatens poor sections of the population who have no political influence. Most women have no say when it comes to discussions about the use and utilization of resources or fundamental decisions.

In the Paris Climate Agreement of 2015, the heads of state agreed to limit global warming to an average of 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. The signatories also agreed on a “gender-responsive” approach to adapting to climate change. This should be based on the best available scientific knowledge.

In order to achieve this goal, the systems that still hold on to old inequalities must be changed. Power relations need to be rethought. This would mean that wealth and resources must be distributed more evenly worldwide and that there must be fairer co-determination and participation in environmental policy issues.

So far, however, there is little evidence of this change, which is why inequality is still the order of the day. The participation of women in adaptation projects is very rare and women’s needs are not sufficiently considered in national climate policy.

However, gender equality is still being pursued in many respects. For example, it is one of the 17 goals of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs for short). The UN climate conferences also led to the establishment of two transnational networks: the civil society GenderCC – Women for Climate Justice and the Global Gender and Climate Alliance (GGCA).

Finally, however, it must be emphasized that the personal consumer behavior of women and men does not have as great an impact on the climate as companies. Around 100 companies already account for 70 percent of greenhouse gas emissions worldwide. Politics and business therefore have the greater influence.

There are also times when men are more threatened by climate change than women. However, this is a rarity. One example, however, is that men, due to their traditional role model, stay longer in their house during forest fires to “protect” it, while women take the rest of the family to safety. This is partly due to toxic masculinity, because of which this behavior is expected of men. This factor is of course not healthy either. However, it has been proven that climate change is discussed too one-sidedly in scientific terms and thus in a strongly stereotypically male way. Women are therefore suffering more overall from the consequences of the climate crisis and many of these consequences were caused by patriarchal structures.

Inhaltliche Quellen:

- https://www.bmfsfj.de/bmfsfj/ministerium/berichte-der-bundesregierung/vierter-gleichstellungsbericht-257274

- https://www.aerztinnenbund.de/Frauen_gesundheitlich_vom_Klimawandel.3715.0.2.html

- https://www.dw.com/de/frauen-klimakrise-stärker-betroffen-maenner-geschlechergerechtigkeit-klimagerechtigkeit-klimawandel/a-62092939

- https://dgvn.de/meldung/klimagerechtigkeit-und-geschlecht-warum-frauen-besonders-anfaellig-fuer-klimawandel-naturkatastroph

- https://unwomen.de/klima-und-gender/

- https://www.welthungerhilfe.de/welternaehrung/rubriken/klima-ressourcen/rolle-von-frauen-im-klimaschutz-aufwerten

- https://www.bmz.de/de/themen/frauenrechte-und-gender/gender-und-klima

- https://www.rnd.de/wissen/klimawandel-und-das-maennliche-geschlecht-gibt-es-den-eco-gender-gap-wirklich-Y7LWRBWX7BAAJF3XKFFA2FZ6GA.html

- https://www.genanet.de/themen/klima

- https://www.spiegel.de/wissenschaft/mensch/studie-maenner-verbrauchen-26-mehr-emissionen-als-frauen-fleisch-und-autos-a-a7358f7c-5470-42af-b5ea-8ba8337b5460

- https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/publication/the-gender-gap-in-carbon-footprints-determinants-and-implications/

- https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/global-social-challenges/2022/07/07/corporations-vs-consumers-who-is-really-to-blame-for-climate-change/

Quellen Abbildungen:

- Abbildung 1: https://www.spiegel.de/karriere/care-arbeit-und-die-haeusliche-gehaltsluecke-warum-das-gleiche-nicht-gerecht-ist-a-a64b128d-d206-4360-8246-5b4bdbb11d16

- Abbildung 2: https://www.carbonbrief.org/mapped-how-climate-change-disproportionately-affects-womens-health/

- Abbildung 3: https://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/europa/greta-thunberg-fridays-for-future-100.html

- Abbildung 4: https://utopia.de/markus-lanz-luisa-neubauer-friedrich-merz-klimapolitik_192757/

- Abbildung 5: https://dgvn.de/meldung/klimagerechtigkeit-und-geschlecht-warum-frauen-besonders-anfaellig-fuer-klimawandel-naturkatastroph

Ocean Acidification

What is the High Seas Treaty and Why Does It Matter?

You may have seen headlines recently about a new global treaty that went into effect just as news broke that the United States would be withdrawing from a number of other international agreements. It’s a confusing time in the world of environmental policy, and Ocean Conservancy is here to help make it clearer while, of course, continuing to protect our ocean.

What is the High Seas Treaty?

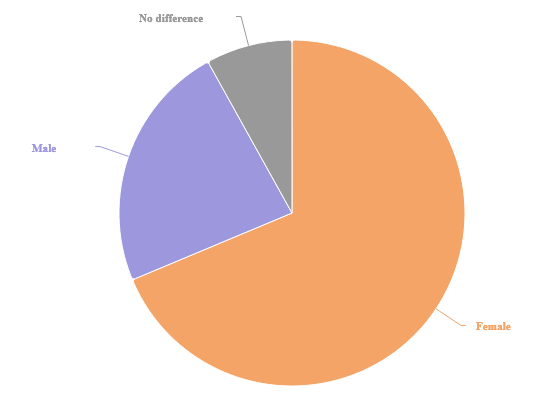

The “High Seas Treaty,” formally known as the Agreement on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Agreement, went into effect on January 17, 2026. We celebrated this win last fall, when the agreement reached the 60 ratifications required for its entry into force. (Since then, an additional 23 countries have joined!) It is the first comprehensive international legal framework dedicated to addressing the conservation and sustainable use of the high seas (the area of the ocean that lies 200 miles beyond the shorelines of individual countries).

To “ensure the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity” of these areas, the BBNJ addresses four core pillars of ocean governance:

- Marine genetic resources: The high seas contain genetic resources (genes of plants, animals and microbes) of great value for pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and food production. The treaty will ensure benefits accrued from the development of these resources are shared equitably amongst nations.

- Area-based management tools such as the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) in international waters. Protecting important areas of the ocean is essential for healthy and resilient ecosystems and marine biodiversity.

- Environmental impact assessments (EIA) will allow us to better understand the potential impacts of proposed activities that may harm the ocean so that they can be managed appropriately.

- Capacity-building and the transfer of marine technology with particular emphasis on supporting developing states. This section of the treaty is designed to ensure all nations benefit from the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity through, for example, the sharing of scientific information.

Get Ocean Updates in Your Inbox

Sign up with your email and never miss an update.

Why is the High Seas Treaty Important?

The BBNJ agreement is legally binding for the countries that have ratified it and is the culmination of nearly two decades of negotiations. Its enactment is a historic milestone for global ocean governance and a significant advancement in the collective protection of marine ecosystems.

The high seas represent about two-thirds of the global ocean, and yet less than 10% of this area is currently protected. This has meant that the high seas have been vulnerable to unregulated or illegal fishing activities and unregulated waste disposal. Recognizing a major governance gap for nearly half of the planet, the agreement puts in place a legal framework to conserve biodiversity.

As it promotes strengthened international cooperation and accountability, the agreement will establish safeguards aimed at preventing and reversing ocean degradation and promoting ecosystem restoration. Furthermore, it will mobilize the international community to develop new legal, scientific, financial and compliance mechanisms, while reinforcing coordination among existing treaties, institutions and organizations to address long-standing governance gaps.

How is Ocean Conservancy Supporting the BBNJ Agreement?

Addressing the global biodiversity crisis is a key focal area for Ocean Conservancy, and the BBNJ agreement adds important new tools to the marine conservation toolbox and a global commitment to better protect the ocean.

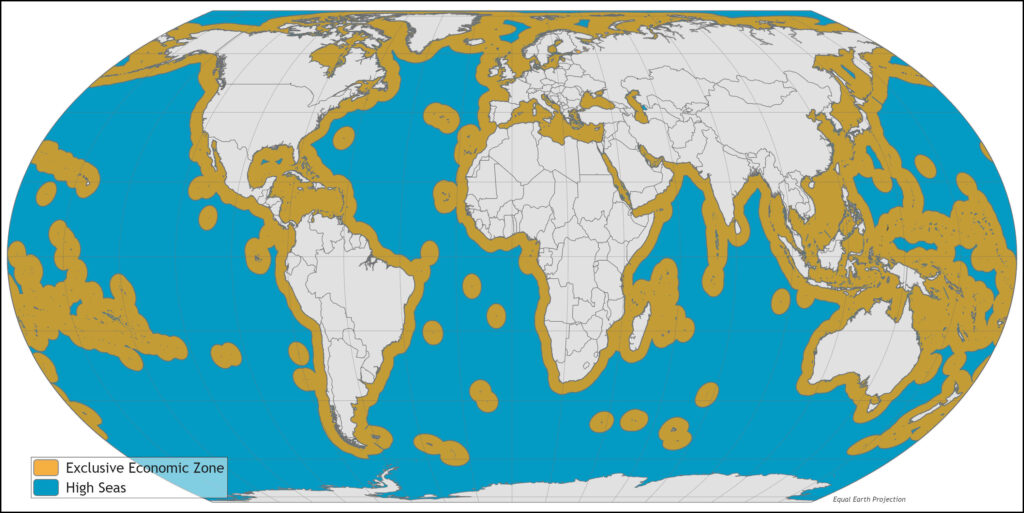

Ocean Conservancy’s efforts to protect the “ocean twilight zone”—an area of the ocean 200-1000m (600-3000 ft) below the surface—is a good example of why the BBNJ agreement is so important. The ocean twilight zone (also known as the mesopelagic zone) harbors incredible marine biodiversity, regulates the climate and supports the health of ocean ecosystems. By some estimates, more than 90% of the fish biomass in the ocean resides in the ocean twilight zone, attracting the interest of those eager to develop new sources of protein for use in aquaculture feed and pet foods.

Done poorly, such development could have major ramifications for the health of our planet, jeopardizing the critical role these species play in regulating the planet’s climate and sustaining commercially and ecologically significant marine species. Species such as tunas (the world’s most valuable fishery), swordfish, salmon, sharks and whales depend upon mesopelagic species as a source of food. Mesopelagic organisms would also be vulnerable to other proposed activities including deep-sea mining.

A significant portion of the ocean twilight zone is in the high seas, and science and policy experts have identified key gaps in ocean governance that make this area particularly vulnerable to future exploitation. The BBNJ agreement’s provisions to assess the impacts of new activities on the high seas before exploitation begins (via EIAs) as well as the ability to proactively protect this area can help ensure the important services the ocean twilight zone provides to our planet continue well into the future.

What’s Next?

Notably, the United States has not ratified the treaty, and, in fact, just a few days before it went into effect, the United States announced its withdrawal from several important international forums, including many focused on the environment. While we at Ocean Conservancy were disappointed by this announcement, there is no doubt that the work will continue.

With the agreement now in force, the first Conference of the Parties (COP1), also referred to as the BBNJ COP, will convene within the next year and will play a critical role in finalizing implementation, compliance and operational details under the agreement. Ocean Conservancy will work with partners to ensure implementation of the agreement is up to the challenge of the global biodiversity crisis.

The post What is the High Seas Treaty and Why Does It Matter? appeared first on Ocean Conservancy.

https://oceanconservancy.org/blog/2026/02/25/high-seas-treaty/

Ocean Acidification

Hälsningar från Åland och Husö biological station

On Åland, the seasons change quickly and vividly. In summer, the nights never really grow dark as the sun hovers just below the horizon. Only a few months later, autumn creeps in and softly cloaks the island in darkness again. The rhythm of the seasons is mirrored by the biological station itself; researchers, professors, and students arrive and depart, bringing with them microscopes, incubators, mesocosms, and field gear to study the local flora and fauna peaking in the mid of summer.

This year’s GAME project is the final chapter of a series of studies on light pollution. Together, we, Pauline & Linus, are studying the effects of artificial light at night (ALAN) on epiphytic filamentous algae. Like the GAME site in Japan, Akkeshi, the biological station Husö here on Åland experiences very little light pollution, making it an ideal place to investigate this subject.

We started our journey at the end of April 2025, just as the islands were waking up from winter. The trees were still bare, the mornings frosty, and the streets quiet. Pauline, a Marine Biology Master’s student from the University of Algarve in Portugal, arrived first and was welcomed by Tony Cederberg, the station manager. Spending the first night alone on the station was unique before the bustle of the project began.

Linus, a Marine Biology Master’s student at Åbo Akademi University in Finland, joined the next day. Husö is the university’s field station and therefore Linus has been here for courses already. However, he was excited to spend a longer stretch at the station and to make the place feel like a second home.

Our first days were spent digging through cupboards and sheds, reusing old materials and tools from previous years, and preparing the frames used by GAME 2023. We chose Hamnsundet as our experimental site, (i.e. the same site that was used for GAME 2023), which is located at the northeast of Åland on the outer archipelago roughly 40 km from Husö. We got permission to deploy the experiments by the local coast guard station, which was perfect. The location is sheltered from strong winds, has electricity access, can be reached by car, and provides the salinity conditions needed for our macroalga, Fucus vesiculosus, to survive.

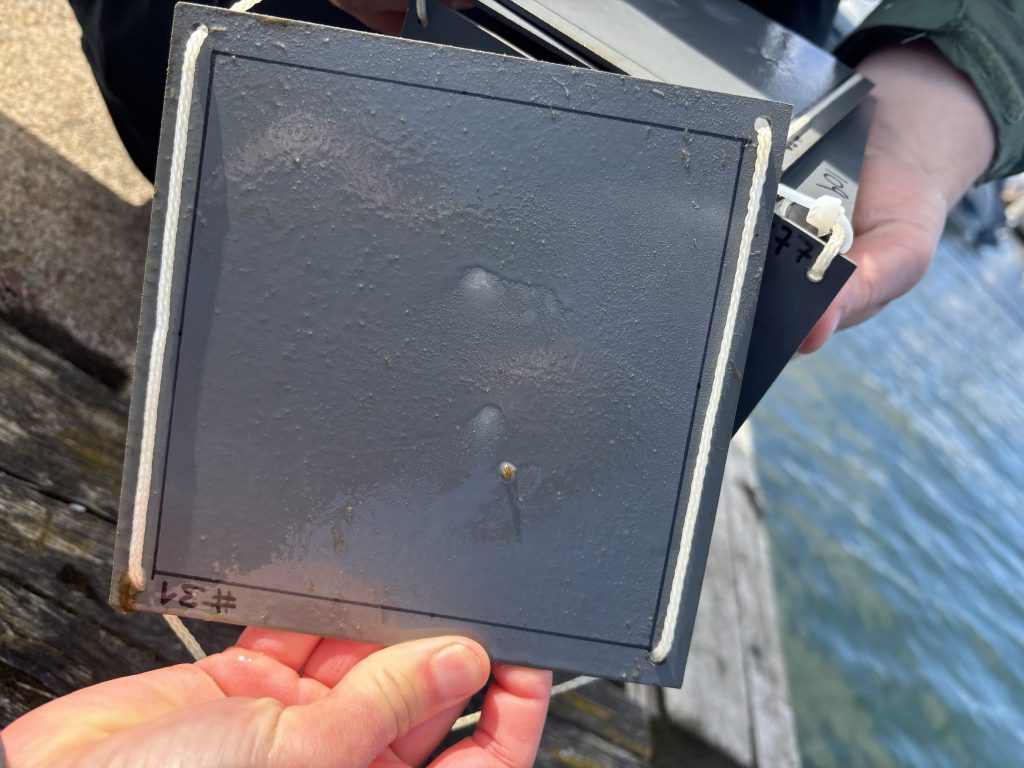

To assess the conditions at the experimental site, we deployed a first set of settlement panels in late April. At first, colonization was slow; only a faint biofilm appeared within two weeks. With the water temperature being still around 7 °C, we decided to give nature more time. Meanwhile, we collected Fucus individuals and practiced the cleaning and the standardizing of the algal thalli for the experiment. Scraping epiphytes off each thallus piece was fiddly, and agreeing on one method was crucial to make sure our results would be comparable to those of other GAME teams.

By early May, building the light setup was a project in itself. Sawing, drilling, testing LEDs, and learning how to secure a 5-meter wooden beam over the water. Our first version bent and twisted until the light pointed sideways instead of straight down onto the algae. Only after buying thicker beams and rebuilding the structure, we finally got a stable and functional setup that could withstand heavy rain and wind. The day we deployed our first experiment at Hamnsundet was cold and rainy but also very rewarding!

Outside of work, we made the most of the island life. We explored Åland by bike, kayak, rowboat, and hiking, visited Ramsholmen National Park during the ramson/ wild garlic bloom, and hiked in Geta with its impressive rock formations and went out boating and fishing in the archipelago. At the station on Husö, cooking became a social event: baking sourdough bread, turning rhubarb from the garden into pies, grilling and making all kind of mushroom dishes. These breaks, in the kitchen and in nature, helped us recharge for the long lab sessions to come.

Every two weeks, it was time to collect and process samples. Snorkeling to the frames, cutting the Fucus and the PVC plates from the lines, and transferring each piece into a freezer bag became our routine. Sampling one experiment took us 4 days and processing all the replicates in the lab easily filled an entire week. The filtering and scraping process was even more time-consuming than we had imagined. It turned out that epiphyte soup is quite thick and clogs filters fastly. This was frustrating at times, since it slowed us down massively.

Over the months, the general community in the water changed drastically. In June, water was still at 10 °C, Fucus carried only a thin layer of diatoms and some very persistent and hard too scrape brown algae (Elachista). In July, everything suddenly exploded: green algae, brown algae, diatoms, cyanobacteria, and tiny zooplankton clogged our filters. With a doubled filtering setup and 6 filtering units, we hoped to compensate for the additional growth.

However, what we had planned as “moderate lab days” turned into marathon sessions. In August, at nearly 20 °C, the Fucus was looking surprisingly clean, but on the PVC a clear winner had emerged. The panels were overrun with the green alga Ulva and looked like the lawn at an abandoned house. Here it was not enough to simply filter the solution, but bigger pieces had to be dried separately. In September, we concluded the last experiment with the help of Sarah from the Cape Verde team, as it was not possible for her to continue on São Vicente, the Cape Verdean island that was most affected by a tropical storm. Our final experiment brought yet another change into community now dominated by brown algae and diatoms. Thankfully our new recruit, sunny autumn weather, and mushroom picking on the side made the last push enjoyable.

By the end of summer, we had accomplished four full experiments. The days were sometimes exhausting but also incredibly rewarding. We learned not only about the ecological effects of artificial light at night, but also about the very practical side of marine research; planning, troubleshooting, and the patience it takes when filtering a few samples can occupy half a day.

Ocean Acidification

What is Coral Bleaching and Why is it Bad News for Coral Reefs?

Coral reefs are beautiful, vibrant ecosystems and a cornerstone of a healthy ocean. Often called the “rainforests of the sea,” they support an extraordinary diversity of marine life from fish and crustaceans to mollusks, sea turtles and more. Although reefs cover less than 1% of the ocean floor, they provide critical habitat for roughly 25% of all ocean species.

Coral reefs are also essential to human wellbeing. These structures reduce the force of waves before they reach shore, providing communities with vital protection from extreme weather such as hurricanes and cyclones. It is estimated that reefs safeguard hundreds of millions of people in more than 100 countries.

What is coral bleaching?

A key component of coral reefs are coral polyps—tiny soft bodied animals related to jellyfish and anemones. What we think of as coral reefs are actually colonies of hundreds to thousands of individual polyps. In hard corals, these tiny animals produce a rigid skeleton made of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). The calcium carbonate provides a hard outer structure that protects the soft parts of the coral. These hard corals are the primary building blocks of coral reefs, unlike their soft coral relatives that don’t secrete any calcium carbonate.

Coral reefs get their bright colors from tiny algae called zooxanthellae. The coral polyps themselves are transparent, and they depend on zooxanthellae for food. In return, the coral polyp provides the zooxanethellae with shelter and protection, a symbiotic relationship that keeps the greater reefs healthy and thriving.

When corals experience stress, like pollution and ocean warming, they can expel their zooxanthellae. Without the zooxanthellae, corals lose their color and turn white, a process known as coral bleaching. If bleaching continues for too long, the coral reef can starve and die.

Ocean warming and coral bleaching

Human-driven stressors, especially ocean warming, threaten the long-term survival of coral reefs. An alarming 77% of the world’s reef areas are already affected by bleaching-level heat stress.

The Great Barrier Reef is a stark example of the catastrophic impacts of coral bleaching. The Great Barrier Reef is made up of 3,000 reefs and is home to thousands of species of marine life. In 2025, the Great Barrier Reef experienced its sixth mass bleaching since 2016. It should also be noted that coral bleaching events are a new thing because of ocean warming, with the first documented in 1998.

Get Ocean Updates in Your Inbox

Sign up with your email and never miss an update.

How you can help

The planet is changing rapidly, and the stakes have never been higher. The ocean has absorbed roughly 90% of the excess heat caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, and the consequences, including coral die-offs, are already visible. With just 2℃ of planetary warming, global coral reef losses are estimated to be up to 99% — and without significant change, the world is on track for 2.8°C of warming by century’s end.

To stop coral bleaching, we need to address the climate crisis head on. A recent study from Scripps Institution of Oceanography was the first of its kind to include damage to ocean ecosystems into the economic cost of climate change – resulting in nearly a doubling in the social cost of carbon. This is the first time the ocean was considered in terms of economic harm caused by greenhouse gas emissions, despite the widespread degradation to ocean ecosystems like coral reefs and the millions of people impacted globally.

This is why Ocean Conservancy advocates for phasing out harmful offshore oil and gas and transitioning to clean ocean energy. In this endeavor, Ocean Conservancy also leads international efforts to eliminate emissions from the global shipping industry—responsible for roughly 1 billion tons of carbon dioxide every year.

But we cannot do this work without your help. We need leaders at every level to recognize that the ocean must be part of the solution to the climate crisis. Reach out to your elected officials and demand ocean-climate action now.

The post What is Coral Bleaching and Why is it Bad News for Coral Reefs? appeared first on Ocean Conservancy.

What is Coral Bleaching and Why is it Bad News for Coral Reefs?

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits