In much of the rest of the country, regional markets help root out inefficiencies, identify reliability needs, and determine which transmission upgrades could increase reliability and lower consumer costs. But not in the Southeast. This article explores Duke Energy’s proposed long-term energy plan, and shows how the continuing resistance to market-based reforms in the Southeast imposes a multi-billion-dollar “reliability tax” on businesses and residential customers.

Read the Blog Series on Duke’s 2024 CPIRP

The Southeast Lacks a Regional Market

Nearly 20 million people across the Southeast are served by our region’s three major electric companies – Duke Energy, Southern Company, and the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). Each of these companies largely builds and operates their own power plants and transmission lines within their own geographic monopoly fiefdoms.

Unlike many parts of the United States, the Southeast has no regional power market to drive least-cost power investment among multiple utilities, to ensure reliability, and/or to jointly plan transmission lines to move power around the region when needed, as shown in this U.S. Wholesale Electricity Markets map by Clean Energy Buyers Institute:

The Southeast lacks a true regional wholesale market. Map courtesy of Clean Energy Buyers Institute’s Organized Wholesale Markets Explainer.

In much of the rest of the country, regional markets have independent system operators that operate generation and transmission over multiple utility service territories on a least-cost basis. This independent planning and operations function helps root out inefficiency, identify reliability needs, and determine which transmission upgrades could increase reliability and lower consumer costs. Because the systems are operated over a wider footprint, fewer total reserves are needed, and thus the region can operate at least as reliably without the need for as many power plants. Regional markets also provide real-time, transparent power system data. In the Southeast, however, the lack of efficient regional coordination and transparent data ultimately means that consumers must pay their local electric companies to build more power plants than would otherwise be needed in order to meet local needs.

Extreme Weather and Projected Growth Drives Duke Energy’s Plan

Duke Energy’s proposed resource plan, called the Carbon Plan in North Carolina and Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) in South Carolina, paints a picture in which climate change-driven weather events and data center-driven electricity sales growth require a massive expansion of ratepayer-funded fossil gas power plants. When Winter Storm Elliott hit the Southeast during the major polar vortex on December 23-24, 2022, Duke had to cut power to hundreds of thousands of customers due largely to the failure of coal- and fossil gas-fueled power plants. While nearby regional markets also experienced similar power plant failures, they avoided customer outages during this storm.

In response to the extreme weather and a large projected growth in electricity demand, Duke now proposes to build more power plants to stand by “just in case” of future power plant failures or extreme load during major weather events. In the industry, these “just in case” power plants are called a “reserve margin.”

A Self Perpetuating Problem with a Billion Dollar Solution

Just the power plants that Duke proposes to build to meet the increases in its reserve margin, would cost customers well over a billion dollars, essentially imposing a localized “reliability tax” on customers that could be avoided with better regional coordination.

To be clear, the reserve plants are not the power plants that will directly serve the new, increased load, but instead are the extra power plants on top of those needed to serve the increased load, which Duke says are necessary as a backup if other plants fail. According to Dr. Jennifer Chen, who submitted testimony to the North Carolina Utilities Commission (NCUC) on behalf of a group of large businesses seeking renewable energy, Duke’s plan increases these reserves from 17% to 22% of peak demand. As Dr. Chen indicates (on page 5), each 1% increase in reserves is roughly equal to a new, medium-sized fossil-fueled power plant that would be paid for by ratepayers.

The increased reserve margins are part of a vicious cycle: because fossil gas have been unreliable–particularly during recent winter storms–Duke argues that we need more fossil gas to make up for the unreliability. This is akin to a doctor attempting to treat symptoms while ignoring the underlying disease causing those symptoms. Until the disease is treated, those symptoms will just keep coming back.

As Dr. Chen points out (pages 11-12 of her testimony), the December 2022 winter storm was the fifth such major disruption in the last decade, and, as utilities around the region build more and more fossil gas power plants to self-insure against winter storms, their customers are more and more exposed to the higher rate of power plant failure during extreme weather. She points out, for instance, that a large, baseload fossil gas plant is more than three times as likely to fail when a polar vortex drops the temperature to 5 below zero, than on a temperate, 50-degree day. In addition, the higher reserves also are significantly driven by including weather patterns in the demand forecast that have not been seen since the early 1980’s, ignoring the subsequent impact of climate change on electricity demand.

This problematic scenario at Duke, in which extreme weather and higher power plant failure rates drive requests for higher reserve margins, is multiplied in similar plans throughout the Southeast.

Markets Help Manage Weather, Growth, and Renewables

The regional markets that are prevalent in most of the rest of the country are designed to reduce the amount of extra power plants that must be built for reliability reserves. As suggested by this report on an increase in southwest U.S. reserve margins from 12% to 15%, and by page 9 of this report from the mid-Atlantic to midwest region, large areas of the country with regional markets are keeping reserve margins down to the (historically still high) 17% range — even with more extreme weather – rather than the 20%+ range that we are now seeing in power company plans across the Southeast.

Lost in the arcane math is the circular conundrum that air pollution from power plants is driving the extreme weather, and the extreme weather makes the power plants more likely to fail, leading to even higher reserve margins.

When Power Plants Performs Better as a Group, Fewer Reserve Plants are Needed

Independently run regional markets seem to be more able to tackle this problem head-on than individual utilities. As Dr. Chen points out, within the largest U.S. regional market (PJM), power plant owners face financial penalties for non-performance that have helped to gradually improve reliability. When all power plants, as a group, perform better, fewer extra plants are needed to be held in reserve. And when a power plant is too unreliable, and the risk of penalties outweighs the benefits to the grid, it can push those power plants to retire instead of continuing to burden the system.

Duke also seeks to justify the extra fossil gas plants by claiming they are needed to backstop increasing renewable energy. This is another “problem” that regional markets can solve: the larger regional pool of resources better accommodates fluctuations in weather as well as low-cost, variable renewable energy, under rules that attempt to be neutral with regard to power generation technology or ownership.

Regional markets are far from perfect, and each has its own strengths and weaknesses. But the current Southeast crisis of crazy weather, load growth, major asset retirements, and renewable energy interconnection backlogs cries out for Southeast utility companies and regulators to take another look at regional, market-based solutions.

Customers should not be saddled with an extra, utility-by-utility “reliability tax” just because utility companies don’t want regional reserve sharing or cost competition.

Read the Blog Series on Duke’s 2024 CPIRP

The post Duke’s Carbon Plan: Part 3: How Many Extra Power Plants Should We Pay For? The Southeast’s Hidden “Reliability Tax” appeared first on SACE | Southern Alliance for Clean Energy.

Renewable Energy

A Lesson from the Early 20th Century

My maternal grandfather was born in southeastern Pennsylvania in 1903 and told me when I was a boy that in the 1920s, times were so good that saloon owners would offer a free lunch, consisting of bread and butter, cheese, cold cuts, pickles and the like. “Sure, they were hoping you’d buy a glass of beer for a nickel, but they really didn’t mind if you didn’t and simply scarfed down a free sandwich.”

My maternal grandfather was born in southeastern Pennsylvania in 1903 and told me when I was a boy that in the 1920s, times were so good that saloon owners would offer a free lunch, consisting of bread and butter, cheese, cold cuts, pickles and the like. “Sure, they were hoping you’d buy a glass of beer for a nickel, but they really didn’t mind if you didn’t and simply scarfed down a free sandwich.”

He went on to tell me that nowadays, there’s a popular slogan: There’s no such thing as a free lunch, “but believe me, there was at the time.”

From today’s perspective of greed and selfishness, this whole story sounds like a fairy tale. Corporations and the congresspeople they own want one thing: to suck the life out of us.

Renewable Energy

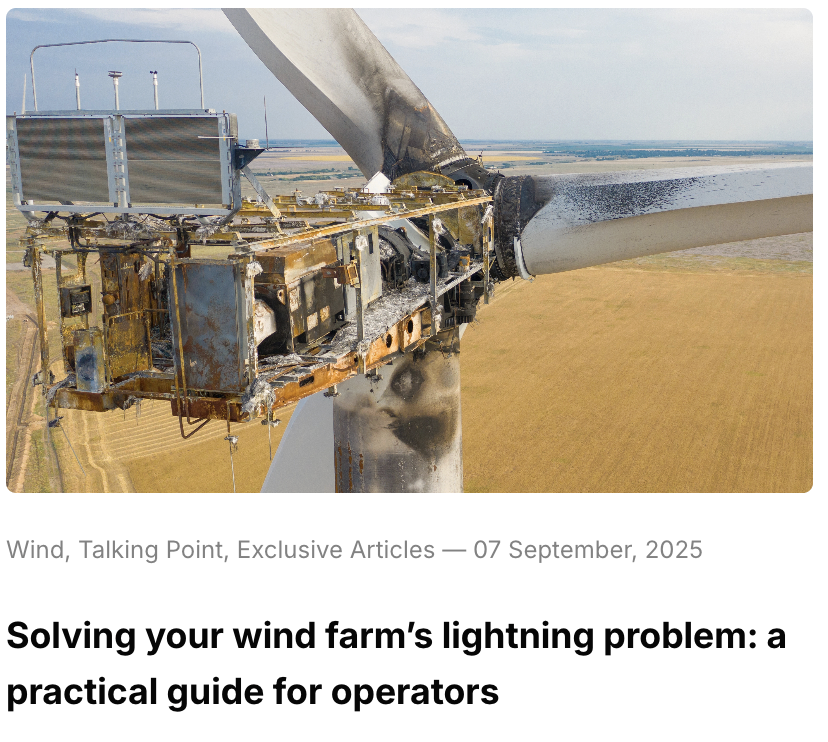

Wind Industry Operations: In Wind’s Next Chapter, Operations take center stage

Wind Industry Operations: In Wind’s Next Chapter, Operations take center stage

This exclusive article originally appeared in PES Wind 4 – 2025 with the title, Operations take center stage in wind’s next chapter. It was written by Allen Hall and other members of the WeatherGuard Lightning Tech team.

As aging fleets, shrinking margins, and new policies reshape the wind sector, wind energy operations are in the spotlight. The industry’s next chapter will be defined not by capacity growth, but by operational excellence, where integrated, predictive maintenance turns data into decisions and reliability into profit.

Wind farm operations are undergoing a fundamental transformation. After hosting hundreds of conversations on the Uptime Wind Energy Podcast, I’ve witnessed a clear pattern: the most successful operators are abandoning reactive maintenance in favor of integrated, predictive strategies. This shift isn’t just about adopting new technologies; it’s about fundamentally rethinking how we manage aging assets in an era of tightening margins and expanding responsibilities.

The evidence was overwhelming at this year’s SkySpecs Customer Forum, where representatives from over 75% of US installed wind capacity gathered to share experiences and strategies. The consensus was clear: those who integrate monitoring, inspection, and repair into a cohesive operational strategy are achieving dramatic improvements in reliability and profitability.

Takeaway: These options have been available to wind energy operations for years; now, adoption is critical.

Why traditional approaches to wind farm operations are failing

Today’s wind operators face an unprecedented convergence of challenges. Fleets installed during the 2010-2015 boom are aging in unexpected ways, revealing design vulnerabilities no one anticipated. Meanwhile, the support infrastructure is crumbling; spare parts have become scarce, OEM support is limited, and insurance companies are tightening coverage just when operators need them most.

The situation is particularly acute following recent policy changes. The One Big Beautiful Bill in the United States has fundamentally altered the economic landscape. PTC farming is no longer viable; turbines must run longer and more reliably than ever before. Engineering teams, already stretched thin, are being asked to manage not just wind assets but solar and battery storage as well. The old playbook simply doesn’t work anymore.

Consider the scope of just one challenge: polyester blade failures. During our podcast conversation with Edo Kuipers of We4Ce, we learned that an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 blades worldwide are experiencing root bushing issues. ‘After a while, blades are simply flying off,’ Kuipers explained. The financial impact of a single blade failure can exceed €300,000 when you factor in replacement costs, lost production, and crane mobilization. Yet innovative repair solutions, like the one developed by We4Ce and CNC Onsite, can address the same problem for €40,000 if caught early. This pattern repeats across every major component. Gearbox failures that once required complete replacement can now be predicted months in advance. Lightning damage that previously caused catastrophic failures can be prevented with inexpensive upgrades and real-time monitoring. All these solutions are based on the principle that predicted maintenance is better than an expensive surprise.

Seeing problems before they happeny, and potential risks

The transformation begins with visibility. Modern monitoring systems reveal problems that traditional methods miss entirely. Eric van Genuchten of Sensing360 shared an eye-opening statistic on our podcast: ‘In planetary gearbox failures, they get 90%, so there’s still 10% of failures they cannot detect.’ That missing 10% represents the catastrophic failures that destroy budgets and production targets. Advanced monitoring technologies are filling these gaps. Sensing360’s fiber optic sensors, for example, detect minute deformations in steel components, revealing load imbalances and fatigue progression invisible to traditional monitoring. ‘We integrate our sensors in steel and make rotating equipment smarter,’ van Genuchten explained.

Other companies are deploying acoustic systems to identify blade delamination, oil analysis for gearbox health, and electrical signature analysis for generator issues. Each technology adds a piece to the puzzle, but the real value comes from integration. The impact of load monitoring alone can be transformative.

As van Genuchten explained, ‘Twenty percent more loading on a gearbox or on a bearing is half of your life. The other way around, twenty percent less loading is double your life.’ With proper monitoring, operators can optimize load distribution across their fleet, extending component life while maximizing production.

But monitoring without action is just expensive data collection. The most successful operators are those who’ve learned to translate sensor data into operational decisions. This requires not just technology but organizational change, breaking down silos between monitoring, maintenance, and management teams.

In Wind Energy Operations, Early intervention makes the million-dollar difference

The economics of early intervention are compelling across every component type. The blade root bushing example from We4Ce illustrates this perfectly. With their solution, early detection means replacing just 24-30 bushings in about 24 hours of drilling work. Wait, and you’re looking at 60+ bushings and 60 hours of work. Early detection doesn’t just prevent catastrophic failure; it makes repairs faster, cheaper, and more reliable.

This principle extends throughout the turbine. Early-stage bearing damage can be addressed through targeted lubrication or minor adjustments. Incipient electrical issues can be resolved with cleaning or connection tightening. Small blade surface cracks can be repaired in a few hours before they propagate into structural damage requiring weeks of work.

Leading operators are implementing tiered response protocols based on monitoring data. Critical issues trigger immediate intervention. Developing problems are scheduled for the next maintenance window. Minor issues are monitored and addressed during routine service. This systematic approach reduces both emergency repairs and unnecessary maintenance, optimizing resource allocation across the fleet.

Turning information into action

While monitoring generates data, platforms like SkySpecs’ Horizon transform that data into operational intelligence. Josh Goryl, SkySpecs’ Chief Revenue Officer, explained their evolution at the recent Customer Forum: ‘I think where we can help our customers is getting all that data into one place.

The game-changer is integration across data types. The company is working to combine performance data with CMS data to provide valuable insights into turbine health. This approach has been informed by operators across the world, who’ve discovered that integrated platforms deliver insights that siloed data can’t.

The platform approach also addresses the reality of shrinking engineering teams managing expanding portfolios. As Goryl noted, many wind engineers are now responsible for solar and battery storage assets as well. One platform managing multiple technologies through a unified interface becomes essential for operational efficiency.

The Integration Imperative for Wind Farm Operations

The most successful operators aren’t just adopting individual technologies; they’re integrating monitoring, inspection, and repair into a seamless operational system. This integration operates at multiple levels.

At the technical level, data from various monitoring systems feeds into unified platforms that provide comprehensive asset visibility. These platforms don’t just display data; they analyze patterns, predict failures, and generate work orders.

At the organizational level, integration means breaking down barriers between departments. This cross-functional collaboration transforms O&M from a cost center into a value driver. Building your improvement roadmap For operators ready to enhance their O&M approach, the path forward involves several key steps:

Assessing the Current State of your Wind Energy Operations

Document your maintenance costs, failure rates, and downtime patterns. Identify which problems consume the most resources and which assets are most critical to your wind farm operations.

Start with targeted pilots Rather than attempting wholesale transformation, begin with focused initiatives targeting your biggest pain points. Whether it’s blade monitoring, gearbox sensors, or repair innovations, starting with your largest issue will help you see the biggest benefit.

• Invest in integration, not just technology: the most sophisticated monitoring system is worthless if its data isn’t acted upon. Ensure your organization has the processes and culture to transform data into decisions – this is the first step to profitability in your wind farm operations.

Build partnerships, not just contracts: look for technology providers and service companies willing to share knowledge, not just deliver services. The goal is building capability, not dependency.

• Measure and iterate: track the impact of each initiative on your key performance indicators. Use lessons learned to refine your approach and guide future investments.

The competitive advantage

The wind industry has reached an inflection point. With increasingly large and complex turbines, monitoring needs to adapt with it. The era of flying blind is over.

In an industry where margins continue to compress and competition intensifies, operational excellence has become a key differentiator. Those who master the integration of monitoring, inspection, and repair will thrive. Those who cling to reactive maintenance face escalating costs and declining competitiveness.

The technology exists. The business case is proven. The early adopters are already reaping the benefits. The question isn’t whether to transform your O&M approach, but how quickly you can adapt to this new reality. In the race to operational excellence, the winners will be those who act decisively to embrace the efficiency revolution reshaping wind operations.

Unless otherwise noted, images here are from We4C Rotorblade Specialist.

Contact us for help understanding your lightning damage, future risks, and how to get more uptime from your equipment.

Download the full article from PES Wind here

Find a practical guide to solving lightning problems and filing better insurance claims here

Wind Industry Operations: In Wind’s Next Chapter, Operations take center stage

Renewable Energy

BladeBUG Tackles Serial Blade Defects with Robotics

Weather Guard Lightning Tech

BladeBUG Tackles Serial Blade Defects with Robotics

Chris Cieslak, CEO of BladeBug, joins the show to discuss how their walking robot is making ultrasonic blade inspections faster and more accessible. They cover new horizontal scanning capabilities for lay down yards, blade root inspections for bushing defects, and plans to expand into North America in 2026.

Sign up now for Uptime Tech News, our weekly newsletter on all things wind technology. This episode is sponsored by Weather Guard Lightning Tech. Learn more about Weather Guard’s StrikeTape Wind Turbine LPS retrofit. Follow the show on YouTube, Linkedin and visit Weather Guard on the web. And subscribe to Rosemary’s “Engineering with Rosie” YouTube channel here. Have a question we can answer on the show? Email us!

Welcome to Uptime Spotlight, shining Light on Wind. Energy’s brightest innovators. This is the Progress Powering Tomorrow.

Allen Hall: Chris, welcome back to the show.

Chris Cieslak: It’s great to be back. Thank you very much for having me on again.

Allen Hall: It’s great to see you in person, and a lot has been happening at Blade Bugs since the last time I saw Blade Bug in person. Yeah, the robot. It looks a lot different and it has really new capabilities.

Chris Cieslak: So we’ve continued to develop our ultrasonic, non-destructive testing capabilities of the blade bug robot.

Um, but what we’ve now added to its capabilities is to do horizontal blade scans as well. So we’re able to do blades that are in lay down yards or blades that have come down for inspections as well as up tower. So we can do up tower, down tower inspections. We’re trying to capture. I guess the opportunity to inspect blades after transportation when they get delivered to site, to look [00:01:00] for any transport damage or anything that might have been missed in the factory inspections.

And then we can do subsequent installation inspections as well to make sure there’s no mishandling damage on those blades. So yeah, we’ve been just refining what we can do with the NDT side of things and improving its capabilities

Joel Saxum: was that need driven from like market response and people say, Hey, we need, we need.

We like the blade blood product. We like what you’re doing, but we need it here. Or do you guys just say like, Hey, this is the next, this is the next thing we can do. Why not?

Chris Cieslak: It was very much market response. We had a lot of inquiries this year from, um, OEMs, blade manufacturers across the board with issues within their blades that need to be inspected on the ground, up the tap, any which way they can.

There there was no, um, rhyme or reason, which was better, but the fact that he wanted to improve the ability of it horizontally has led the. Sort of modifications that you’ve seen and now we’re doing like down tower, right? Blade scans. Yeah. A really fast breed. So

Joel Saxum: I think the, the important thing there is too is that because of the way the robot is built [00:02:00] now, when you see NDT in a factory, it’s this robot rolls along this perfectly flat concrete floor and it does this and it does that.

But the way the robot is built, if a blade is sitting in a chair trailing edge up, or if it’s flap wise, any which way the robot can adapt to, right? And the idea is. We, we looked at it today and kind of the new cage and the new things you have around it with all the different encoders and for the heads and everything is you can collect data however is needed.

If it’s rasterized, if there’s a vector, if there’s a line, if we go down a bond line, if we need to scan a two foot wide path down the middle of the top of the spa cap, we can do all those different things and all kinds of orientations. That’s a fantastic capability.

Chris Cieslak: Yeah, absolutely. And it, that’s again for the market needs.

So we are able to scan maybe a meter wide in one sort of cord wise. Pass of that probe whilst walking in the span-wise direction. So we’re able to do that raster scan at various spacing. So if you’ve got a defect that you wanna find that maximum 20 mil, we’ll just have a 20 mil step [00:03:00] size between each scan.

If you’ve got a bigger tolerance, we can have 50 mil, a hundred mil it, it’s so tuneable and it removes any of the variability that you get from a human to human operator doing that scanning. And this is all about. Repeatable, consistent high quality data that you can then use to make real informed decisions about the state of those blades and act upon it.

So this is not about, um, an alternative to humans. It’s just a better, it’s just an evolution of how humans do it. We can just do it really quick and it’s probably, we, we say it’s like six times faster than a human, but actually we’re 10 times faster. We don’t need to do any of the mapping out of the blade, but it’s all encoded all that data.

We know where the robot is as we walk. That’s all captured. And then you end up with really. Consistent data. It doesn’t matter who’s operating a robot, the robot will have those settings preset and you just walk down the blade, get that data, and then our subject matter experts, they’re offline, you know, they are in their offices, warm, cozy offices, reviewing data from multiple sources of robots.

And it’s about, you know, improving that [00:04:00] efficiency of getting that report out to the customer and letting ’em know what’s wrong with their blades, actually,

Allen Hall: because that’s always been the drawback of, with NDT. Is that I think the engineers have always wanted to go do it. There’s been crush core transportation damage, which is sometimes hard to see.

You can maybe see a little bit of a wobble on the blade service, but you’re not sure what’s underneath. Bond line’s always an issue for engineering, but the cost to take a person, fly them out to look at a spot on a blade is really expensive, especially someone who is qualified. Yeah, so the, the difference now with play bug is you can have the technology to do the scan.

Much faster and do a lot of blades, which is what the de market demand is right now to do a lot of blades simultaneously and get the same level of data by the review, by the same expert just sitting somewhere else.

Chris Cieslak: Absolutely.

Joel Saxum: I think that the quality of data is a, it’s something to touch on here because when you send someone out to the field, it’s like if, if, if I go, if I go to the wall here and you go to the wall here and we both take a paintbrush, we paint a little bit [00:05:00] different, you’re probably gonna be better.

You’re gonna be able to reach higher spots than I can.

Allen Hall: This is true.

Joel Saxum: That’s true. It’s the same thing with like an NDT process. Now you’re taking the variability of the technician out of it as well. So the data quality collection at the source, that’s what played bug ducts.

Allen Hall: Yeah,

Joel Saxum: that’s the robotic processes.

That is making sure that if I scan this, whatever it may be, LM 48.7 and I do another one and another one and another one, I’m gonna get a consistent set of quality data and then it’s goes to analysis. We can make real decisions off.

Allen Hall: Well, I, I think in today’s world now, especially with transportation damage and warranties, that they’re trying to pick up a lot of things at two years in that they could have picked up free installation.

Yeah. Or lifting of the blades. That world is changing very rapidly. I think a lot of operators are getting smarter about this, but they haven’t thought about where do we go find the tool.

Speaker: Yeah.

Allen Hall: And, and I know Joel knows that, Hey, it, it’s Chris at Blade Bug. You need to call him and get to the technology.

But I think for a lot of [00:06:00] operators around the world, they haven’t thought about the cost They’re paying the warranty costs, they’re paying the insurance costs they’re paying because they don’t have the set of data. And it’s not tremendously expensive to go do. But now the capability is here. What is the market saying?

Is it, is it coming back to you now and saying, okay, let’s go. We gotta, we gotta mobilize. We need 10 of these blade bugs out here to go, go take a scan. Where, where, where are we at today?

Chris Cieslak: We’ve hads. Validation this year that this is needed. And it’s a case of we just need to be around for when they come back round for that because the, the issues that we’re looking for, you know, it solves the problem of these new big 80 a hundred meter plus blades that have issues, which shouldn’t.

Frankly exist like process manufacturer issues, but they are there. They need to be investigated. If you’re an asset only, you wanna know that. Do I have a blade that’s likely to fail compared to one which is, which is okay? And sort of focus on that and not essentially remove any uncertainty or worry that you have about your assets.

’cause you can see other [00:07:00] turbine blades falling. Um, so we are trying to solve that problem. But at the same time, end of warranty claims, if you’re gonna be taken over these blades and doing the maintenance yourself, you wanna know that what you are being given. It hasn’t gotten any nasties lurking inside that’s gonna bite you.

Joel Saxum: Yeah.

Chris Cieslak: Very expensively in a few years down the line. And so you wanna be able to, you know, tick a box, go, actually these are fine. Well actually these are problems. I, you need to give me some money so I can perform remedial work on these blades. And then you end of life, you know, how hard have they lived?

Can you do an assessment to go, actually you can sweat these assets for longer. So we, we kind of see ourselves being, you know, useful right now for the new blades, but actually throughout the value chain of a life of a blade. People need to start seeing that NDT ultrasonic being one of them. We are working on other forms of NDT as well, but there are ways of using it to just really remove a lot of uncertainty and potential risk for that.

You’re gonna end up paying through the, you know, through the, the roof wall because you’ve underestimated something or you’ve missed something, which you could have captured with a, with a quick inspection.

Joel Saxum: To [00:08:00] me, NDT has been floating around there, but it just hasn’t been as accessible or easy. The knowledge hasn’t been there about it, but the what it can do for an operator.

In de-risking their fleet is amazing. They just need to understand it and know it. But you guys with the robotic technology to me, are bringing NDT to the masses

Chris Cieslak: Yeah.

Joel Saxum: In a way that hasn’t been able to be done, done before

Chris Cieslak: that. And that that’s, we, we are trying to really just be able to roll it out at a way that you’re not limited to those limited experts in the composite NDT world.

So we wanna work with them, with the C-N-C-C-I-C NDTs of this world because they are the expertise in composite. So being able to interpret those, those scams. Is not a quick thing to become proficient at. So we are like, okay, let’s work with these people, but let’s give them the best quality data, consistent data that we possibly can and let’s remove those barriers of those limited people so we can roll it out to the masses.

Yeah, and we are that sort of next level of information where it isn’t just seen as like a nice to have, it’s like an essential to have, but just how [00:09:00] we see it now. It’s not NDT is no longer like, it’s the last thing that we would look at. It should be just part of the drones. It should inspection, be part of the internal crawlers regimes.

Yeah, it’s just part of it. ’cause there isn’t one type of inspection that ticks all the boxes. There isn’t silver bullet of NDT. And so it’s just making sure that you use the right system for the right inspection type. And so it’s complementary to drones, it’s complimentary to the internal drones, uh, crawlers.

It’s just the next level to give you certainty. Remove any, you know, if you see something indicated on a a on a photograph. That doesn’t tell you the true picture of what’s going on with the structure. So this is really about, okay, I’ve got an indication of something there. Let’s find out what that really is.

And then with that information you can go, right, I know a repair schedule is gonna take this long. The downtime of that turbine’s gonna be this long and you can plan it in. ’cause everyone’s already got limited budgets, which I think why NDT hasn’t taken off as it should have done because nobody’s got money for more inspections.

Right. Even though there is a money saving to be had long term, everyone is fighting [00:10:00] fires and you know, they’ve really got a limited inspection budget. Drone prices or drone inspections have come down. It’s sort, sort of rise to the bottom. But with that next value add to really add certainty to what you’re trying to inspect without, you know, you go to do a day repair and it ends up being three months or something like, well

Allen Hall: that’s the lightning,

Joel Saxum: right?

Allen Hall: Yeah. Lightning is the, the one case where every time you start to scarf. The exterior of the blade, you’re not sure how deep that’s going and how expensive it is. Yeah, and it always amazes me when we talk to a customer and they’re started like, well, you know, it’s gonna be a foot wide scarf, and now we’re into 10 meters and now we’re on the inside.

Yeah. And the outside. Why did you not do an NDT? It seems like money well spent Yeah. To do, especially if you have a, a quantity of them. And I think the quantity is a key now because in the US there’s 75,000 turbines worldwide, several hundred thousand turbines. The number of turbines is there. The number of problems is there.

It makes more financial sense today than ever because drone [00:11:00]information has come down on cost. And the internal rovers though expensive has also come down on cost. NDT has also come down where it’s now available to the masses. Yeah. But it has been such a mental barrier. That barrier has to go away. If we’re going going to keep blades in operation for 25, 30 years, I

Joel Saxum: mean, we’re seeing no

Allen Hall: way you can do it

Joel Saxum: otherwise.

We’re seeing serial defects. But the only way that you can inspect and or control them is with NDT now.

Allen Hall: Sure.

Joel Saxum: And if we would’ve been on this years ago, we wouldn’t have so many, what is our term? Blade liberations liberating

Chris Cieslak: blades.

Joel Saxum: Right, right.

Allen Hall: What about blade route? Can the robot get around the blade route and see for the bushings and the insert issues?

Chris Cieslak: Yeah, so the robot can, we can walk circumferentially around that blade route and we can look for issues which are affecting thousands of blades. Especially in North America. Yeah.

Allen Hall: Oh yeah.

Chris Cieslak: So that is an area that is. You know, we are lucky that we’ve got, um, a warehouse full of blade samples or route down to tip, and we were able to sort of calibrate, verify, prove everything in our facility to [00:12:00] then take out to the field because that is just, you know, NDT of bushings is great, whether it’s ultrasonic or whether we’re using like CMS, uh, type systems as well.

But we can really just say, okay, this is the area where the problem is. This needs to be resolved. And then, you know, we go to some of the companies that can resolve those issues with it. And this is really about played by being part of a group of technologies working together to give overall solutions

Allen Hall: because the robot’s not that big.

It could be taken up tower relatively easily, put on the root of the blade, told to walk around it. You gotta scan now, you know. It’s a lot easier than trying to put a technician on ropes out there for sure.

Chris Cieslak: Yeah.

Allen Hall: And the speed up it.

Joel Saxum: So let’s talk about execution then for a second. When that goes to the field from you, someone says, Chris needs some help, what does it look like?

How does it work?

Chris Cieslak: Once we get a call out, um, we’ll do a site assessment. We’ve got all our rams, everything in place. You know, we’ve been on turbines. We know the process of getting out there. We’re all GWO qualified and go to site and do their work. Um, for us, we can [00:13:00] turn up on site, unload the van, the robot is on a blade in less than an hour.

Ready to inspect? Yep. Typically half an hour. You know, if we’ve been on that same turbine a number of times, it’s somewhere just like clockwork. You know, muscle memory comes in, you’ve got all those processes down, um, and then it’s just scanning. Our robot operator just presses a button and we just watch it perform scans.

And as I said, you know, we are not necessarily the NDT experts. We obviously are very mindful of NDT and know what scans look like. But if there’s any issues, we have a styling, we dial in remote to our supplement expert, they can actually remotely take control, change the settings, parameters.

Allen Hall: Wow.

Chris Cieslak: And so they’re virtually present and that’s one of the beauties, you know, you don’t need to have people on site.

You can have our general, um, robot techs to do the work, but you still have that comfort of knowing that the data is being overlooked if need be by those experts.

Joel Saxum: The next level, um, commercial evolution would be being able to lease the kit to someone and or have ISPs do it for [00:14:00] you guys kinda globally, or what is the thought

Chris Cieslak: there?

Absolutely. So. Yeah, so we to, to really roll this out, we just wanna have people operate in the robots as if it’s like a drone. So drone inspection companies are a classic company that we see perfectly aligned with. You’ve got the sky specs of this world, you know, you’ve got drone operator, they do a scan, they can find something, put the robot up there and get that next level of information always straight away and feed that into their systems to give that insight into that customer.

Um, you know, be it an OEM who’s got a small service team, they can all be trained up. You’ve got general turbine technicians. They’ve all got G We working at height. That’s all you need to operate the bay by road, but you don’t need to have the RAA level qualified people, which are in short supply anyway.

Let them do the jobs that we are not gonna solve. They can do the big repairs we are taking away, you know, another problem for them, but giving them insights that make their job easier and more successful by removing any of those surprises when they’re gonna do that work.

Allen Hall: So what’s the plans for 2026 then?

Chris Cieslak: 2026 for us is to pick up where 2025 should have ended. [00:15:00] So we were, we were meant to be in the States. Yeah. On some projects that got postponed until 26. So it’s really, for us North America is, um, what we’re really, as you said, there’s seven, 5,000 turbines there, but there’s also a lot of, um, turbines with known issues that we can help determine which blades are affected.

And that involves blades on the ground, that involves blades, uh, that are flying. So. For us, we wanna get out to the states as soon as possible, so we’re working with some of the OEMs and, and essentially some of the asset owners.

Allen Hall: Chris, it’s so great to meet you in person and talk about the latest that’s happening.

Thank you. With Blade Bug, if people need to get ahold of you or Blade Bug, how do they do that?

Chris Cieslak: I, I would say LinkedIn is probably the best place to find myself and also Blade Bug and contact us, um, through that.

Allen Hall: Alright, great. Thanks Chris for joining us and we will see you at the next. So hopefully in America, come to America sometime.

We’d love to see you there.

Chris Cieslak: Thank you very [00:16:00] much.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits