High temperatures caused by climate change are driving an ongoing drought in the Middle East, according to a new rapid attribution analysis by the World Weather Attribution service.

Large parts of Iraq, Iran and Syria have been gripped by an intense drought for years. Low rainfall and high temperatures have caused crops to fail and driven water shortages across the region, pushing millions of people into food insecurity.

The study finds that, between July 2020 and June 2023, climate change made the drought more intense – mainly due to high temperatures that dried out the soil.

In a world without climate change, the dry period would not have even been severe enough to be called a drought, the study notes.

The authors find that climate change also made the event more likely.

In today’s climate, the drought in Iran was a one-in-five year event. However, without the influence of climate change, it would have been a one-in-80 year event.

Meanwhile, in the Tigris-Euphrates river basin that encompasses much of Iraq and Syria, climate change increased the likelihood of the drought from a one-in-250 to a one-in-10 year event.

The analysis shows that droughts of this intensity are “not rare anymore” due to climate change, one study author told a press briefing.

The study highlights that other factors, including conflict, water management and land degradation have also contributed to the severe impacts of the drought.

The Fertile Crescent

Tucked between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and the Mediterranean Sea, the Fertile Crescent – named for its rich soils – is often referred to as the “cradle of civilisation”. For thousands of years, this Middle Eastern region has been ideal for agriculture, allowing rural communities to cultivate crops and raise animals.

Today, the area is facing a severe multi-year drought driven by high temperatures and low rainfall. “In an already water-stressed region, agricultural practices consume 80%, on average, of freshwater resources,” Rana El Hajj, a senior technical adviser at the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre and author on the study, told a press briefing.

As the drought has caused crops to fail, tens of millions of people across Iraq, Iran and Syria are facing the combined impacts of water shortages and food insecurity.

In Syria, where around 70% of the wheat crop relies on rainfall, agricultural production was 80% lower in 2022 than it was in 2020.

The resulting spike in food prices has driven millions of people into poverty and hunger. The World Food Programme estimates that 12.1 million Syrians – more than half the population – are facing hunger, while another 2.9 million people are at risk of becoming food insecure.

In Iraq, the 2020-21 rainfall season was the second driest in 40 years, leading to a 29% and 73% drop in water flow in the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, respectively.

In April 2022, the Iraqi ministry of water resources warned that the country’s water reserves had halved since the previous year due to intense heat and low rainfall.

Almost 90% of Iraq’s rain-fed crops – mostly wheat and barley – failed in 2022. One Iraqi farmer called the water shortage a “catastrophic crisis“, explaining that “most of our agricultural lands have been transformed into barren scorching desert lands which lack basic living necessities”.

In Iran, only 180mm of rain fell across the country between September 2021 and September 2022 – a decline of about 24% compared to the long-term average. The drought has led to shortages of drinking water, crop failure and low hydropower output, and many Iranian farmers have been forced to travel to cities to find work.

The low rainfall came as intense heat baked the Middle East. Over the past few years, many regions have faced temperatures above 50C.

Multiyear drought

There are many ways to define drought. Hydrological drought focuses on the amount of rainfall a region receives, while pluvial droughts focus on surface and groundwater flows.

This study investigates agricultural drought, using a measure called the “standardised precipitation evapotranspiration index” (SPEI) – an index used to determine the onset, duration and magnitude of drought conditions in comparison with typical conditions.

Dr Ben Clarke – a researcher at Imperial College London’s Grantham Institute and author on the study – told a press briefing that SPEI gives a measure of available water balance on the land surface.

The study investigates two regions – Iran, and the crescent around the Euphrates and Tigris rivers which encompasses large parts of Iraq and Syria.

The map below shows SPEI in these regions over the 36 months between July 2020 and June 2023. The study regions are outlined in grey, with the Tigris-Euphrates river basin on the left and Iran to the right. The areas of darker shading indicate a more severe drought.

Over both regions, 2020-23 was the second worst drought on record, the study finds.

Dr Elham Ghasemifar is a researcher in satellite climatology at Iran’s Tarbiat Modares University and was not involved in the study. He tells Carbon Brief that according to his research, the seasonality of agricultural drought is different across the three countries. Iraq and Iran see the most severe droughts in summer and spring, while Syria sees them in autumn, he says.

Attribution

Attribution is a fast-growing field of climate science that aims to identify the “fingerprint” of climate change on extreme-weather events. In this study, the authors investigate the impact of climate change on drought across Iran, Iraq and Syria.

To put the drought into its historical context and determine how unlikely it was, the authors analysed a timeseries of SPEI for each region. They also use climate models to compare the world as it is today to a “counterfactual” world without human-caused climate change.

The authors find that in today’s climate, which has already warmed by around 1.2C above pre-industrial temperatures due to human-caused climate change, the drought in Iran was a one-in-five year event. Without the influence of climate change, it would have been a one-in-80 year event, they find.

If the planet continues to heat, reaching a warming level of 2C above pre-industrial temperatures, Iran could expect a drought of this severity every other year, the authors add.

The graphic below illustrates these results, where a pink dot indicates the number of years in every 81 that an event like the 2020-23 drought over Iran would be seen at different warming levels.

The authors also performed the same analysis for the Tigris-Euphrates river basin in Syria and Iraq. They find that in a pre-industrial climate, today’s climate and a 2C climate, the drought would be expected once every 250, 10 and five years, respectively. These results are shown in the graphic below.

The study shows that droughts such as those recorded in Iran, Iraq and Syria over 2020-23 are “not rare anymore”, Prof Mohammad Rahimi – a professor of climatology at Iran’s Semnan University and author on the study – told a press briefing.

The authors also find that, in both regions, climate change made the drought more intense. Without the influence of climate change, neither event would have even been classified as a drought, the study suggests.

To look more closely at the causes of the drought, the authors also analyse temperature and rainfall trends separately. They find that the change in rainfall was “relatively extreme, but not necessarily affected by climate change”, while the temperatures recorded would have been “virtually impossible” with climate change, Clarke told the press briefing.

This indicates that the drought was caused by “naturally low precipitation coinciding with really, really high temperatures”, Clarke explained.

(These findings are yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal. However, the methods used in the analysis have been published in previous attribution studies.)

Water insecurity

High temperatures and low rainfall are not the only drivers of water insecurity across Iraq, Iran and Syria. Rajj told the press briefing that other human-caused factors, such as poor water management, land-use change, rapid urbanisation and conflict are also key.

In Syria, more than a decade of war has resulted in underdeveloped irrigation infrastructure, as well as a “devastated economy, damaged infrastructure and increasing poverty”, says the New York Times. Many farmers have also been forced from their lands by shelling, and the the Syrian currency has collapsed to a record low.

Water scarcity is also leading to tension between countries in the Middle East, with many regions building dams or overusing water at the expense of others.

For example, the Tigris and Euphrates rivers are Iraq’s primary sources of water, but both rivers originate in Turkey and flow through Syria first. As Turkey and Syria began developing hydropower projects on the two rivers in the 1970s, water flow to Iraq began to dwindle. Today, dams along the rivers have reduced inflow to Iraq by around 30-40%.

The post Climate change: Intensity of ongoing drought in Syria, Iraq and Iran ‘not rare anymore’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate change: Intensity of ongoing drought in Syria, Iraq and Iran ‘not rare anymore’

Climate Change

Southern Right Whales Are Having Fewer Calves; Scientists Say a Warming Ocean Is to Blame

After decades of recovery from commercial whaling, climate change is now threatening the whales’ future.

Southern right whales—once driven to near-extinction by industrial hunting in the 19th and 20th centuries—have long been regarded as a conservation success. After the International Whaling Commission banned commercial whaling in the 1980s, populations began a slow but steady rebound. New research, however, suggests climate change may be undermining that recovery.

Southern Right Whales Are Having Fewer Calves; Scientists Say a Warming Ocean Is to Blame

Climate Change

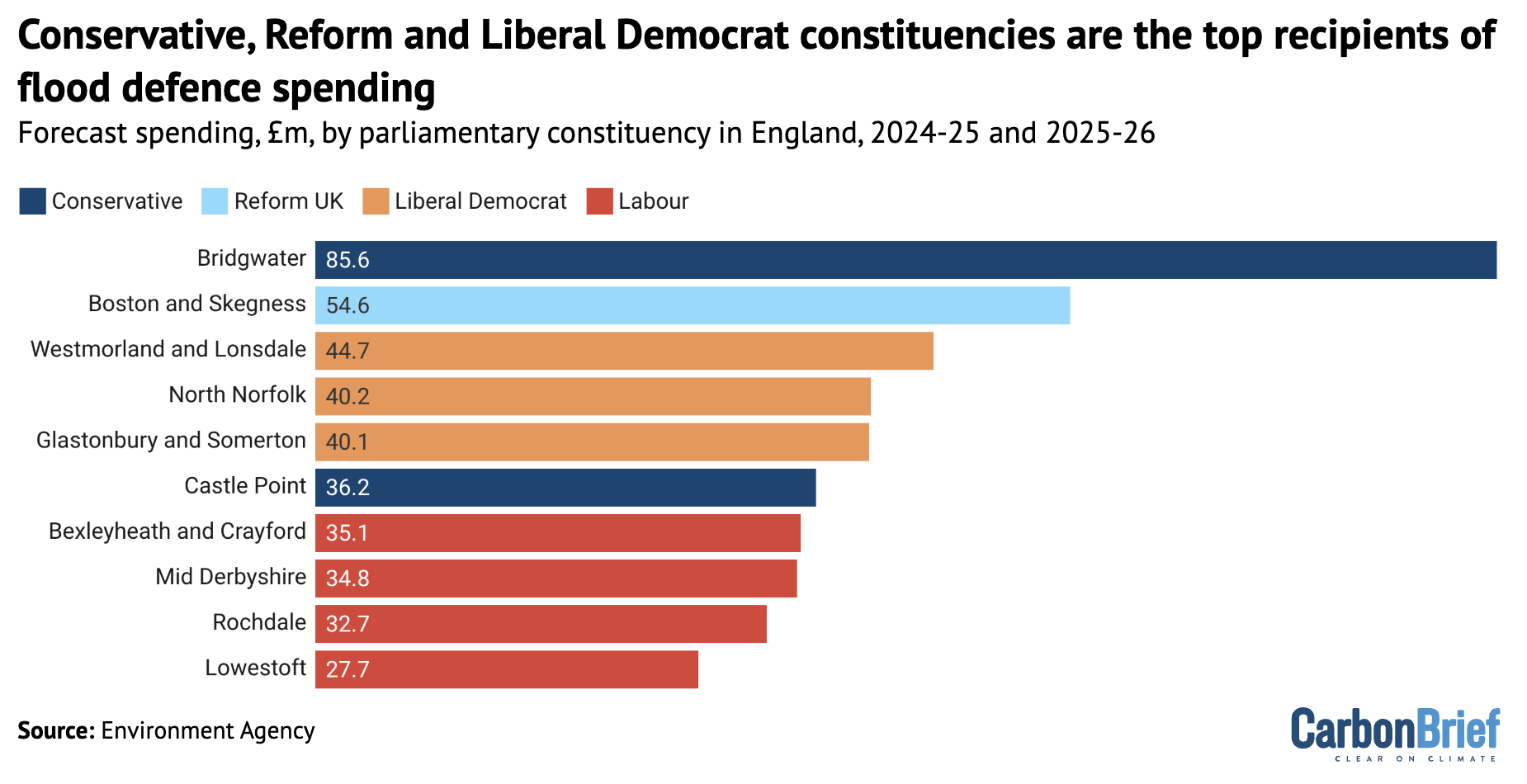

Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding

The Lincolnshire constituency held by Richard Tice, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of the hard-right Reform party, has been pledged at least £55m in government funding for flood defences since 2024.

This investment in Boston and Skegness is the second-largest sum for a single constituency from a £1.4bn flood-defence fund for England, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

Flooding is becoming more likely and more extreme in the UK due to climate change.

Yet, for years, governments have failed to spend enough on flood defences to protect people, properties and infrastructure.

The £1.4bn fund is part of the current Labour government’s wider pledge to invest a “record” £7.9bn over a decade on protecting hundreds of thousands of homes and businesses from flooding.

As MP for one of England’s most flood-prone regions, Tice has called for more investment in flood defences, stating that “we cannot afford to ‘surrender the fens’ to the sea”.

He is also one of Reform’s most vocal opponents of climate action and what he calls “net stupid zero”. He denies the scientific consensus on climate change and has claimed, falsely and without evidence, that scientists are “lying”.

Flood defences

Last year, the government said it would invest £2.65bn on flood and coastal erosion risk management (FCERM) schemes in England between April 2024 and March 2026.

This money was intended to protect 66,500 properties from flooding. It is part of a decade-long Labour government plan to spend more than £7.9bn on flood defences.

There has been a consistent shortfall in maintaining England’s flood defences, with the Environment Agency expecting to protect fewer properties by 2027 than it had initially planned.

The Climate Change Committee (CCC) has attributed this to rising costs, backlogs from previous governments and a lack of capacity. It also points to the strain from “more frequent and severe” weather events, such as storms in recent years that have been amplified by climate change.

However, the CCC also said last year that, if the 2024-26 spending programme is delivered, it would be “slightly closer to the track” of the Environment Agency targets out to 2027.

The government has released constituency-level data on which schemes in England it plans to fund, covering £1.4bn of the 2024-26 investment. The other half of the FCERM spending covers additional measures, from repairing existing defences to advising local authorities.

The map below shows the distribution of spending on FCERM schemes in England over the past two years, highlighting the constituency of Richard Tice.

By far the largest sum of money – £85.6m in total – has been committed to a tidal barrier and various other defences in the Somerset constituency of Bridgwater, the seat of Conservative MP Ashley Fox.

Over the first months of 2026, the south-west region has faced significant flooding and Fox has called for more support from the government, citing “climate patterns shifting and rainfall intensifying”.

He has also backed his party’s position that “the 2050 net-zero target is impossible” and called for more fossil-fuel extraction in the North Sea.

Tice’s east-coast constituency of Boston and Skegness, which is highly vulnerable to flooding from both rivers and the sea, is set to receive £55m. Among the supported projects are beach defences from Saltfleet to Gibraltar Point and upgrades to pumping stations.

Overall, Boston and Skegness has the second-largest portion of flood-defence funding, as the chart below shows. Constituencies with Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs occupied the other top positions.

Overall, despite Labour MPs occupying 347 out of England’s 543 constituencies – nearly two-thirds of the total – more than half of the flood-defence funding was distributed to constituencies with non-Labour MPs. This reflects the flood risk in coastal and rural areas that are not traditional Labour strongholds.

Reform funding

While Reform has just eight MPs, representing 1% of the population, its constituencies have been assigned 4% of the flood-defence funding for England.

Nearly all of this money was for Tice’s constituency, although party leader Nigel Farage’s coastal Clacton seat in Kent received £2m.

Reform UK is committed to “scrapping net-zero” and its leadership has expressed firmly climate-sceptic views.

Much has been made of the disconnect between the party’s climate policies and the threat climate change poses to its voters. Various analyses have shown the flood risk in Reform-dominated areas, particularly Lincolnshire.

Tice has rejected climate science, advocated for fossil-fuel production and criticised Environment Agency flood-defence activities. Yet, he has also called for more investment in flood defences, stating that “we cannot afford to ‘surrender the fens’ to the sea”.

This may reflect Tice’s broader approach to climate change. In a 2024 interview with LBC, he said:

“Where you’ve got concerns about sea level defences and sea level rise, guess what? A bit of steel, a bit of cement, some aggregate…and you build some concrete sea level defences. That’s how you deal with rising sea levels.”

While climate adaptation is viewed as vital in a warming world, there are limits on how much societies can adapt and adaptation costs will continue to increase as emissions rise.

The post Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding

Climate Change

US Government Is Accelerating Coral Reef Collapse, Scientists Warn

Proposed Endangered Species Act rollbacks and military expansions are leaving the Pacific’s most diverse coral reefs legally defenseless.

Ritidian Point, at the northern tip of Guam, is home to an ancient limestone forest with panoramic vistas of warm Pacific waters. Stand here in early spring and you might just be lucky enough to witness a breaching humpback whale as they migrate past. But listen and you’ll be struck by the cacophony of the island’s live-fire testing range.

US Government Is Accelerating Coral Reef Collapse, Scientists Warn

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits