The COP30 climate summit in Belém will put adaptation to a warming world front and centre, with the aim of moving negotiations from technical debate to deciding how to measure adaptation progress and accelerating action on the ground, according to Alice Amorim, Brazil’s COP30 programme director.

At the mid-year UN talks in Bonn, countries reached a compromise on work to select a set of 100 indicators this year for the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA), which is part of the Paris Agreement.

But a key sticking point has been how to track funding for vulnerable communities to become more resilient to climate shifts – which affect everything from agriculture to water and infrastructure – in a way that can help ensure that developed countries are providing adequate support to developing nations.

IEA says some oil and gas projects must shut early to meet 1.5C limit

A meeting of technical experts in late August narrowed down the list of GGA indicators to 113, but was unable to agree on how to monitor finance for adaptation, according to a summary released this week.

With the negotiations set to continue at COP30, Amorim told this month’s Africa Climate Summit in Addis Ababa that she hopes countries will finally agree on the indicators in Belém, adding that the Brazil conference – being described as an “implementation COP” – must go further to shape a system that can quickly turn those decisions into real-world results.

“This is a moment where we don’t need to wait anymore for all parties to agree on what needs to happen to make adaptation finance flow to Africa, to Latin America, to the small island states and so on. It’s about acting upon it, it’s about moving from commitments to practice,” Amorim said.

She added that there should be no more delay in investing in adaptation and resilience-building because resources are needed urgently to build climate-safe infrastructure and implement national adaptation plans.

COP30 will not launch “shiny new initiatives”, she added, but will bring existing solutions “to understand what is already happening on the ground that needs to be leveraged and what are the gaps that financial sector players and policy makers need to address”.

An existing goal to double adaptation finance to around $40 billion a year by 2025 – agreed at COP26 – expires this year, and experts say it has helped drive more money into adaptation.

The Least Developed Countries group has called for a new goal of tripling finance from 2022 levels by 2030 to close to $100 billion a year. But even that would not close the gap which the UN estimates to be $160 billion-$340 billion a year by 2030.

Addis summit gets behind adaptation

Brazil’s Amorim told the Africa climate summit in Ethiopia last week that the need for adaptation “is clear and tangible” on the continent. What is missing, however, are the conditions to drive it in a much wider and faster way, she added.

Adapting to climate change by shoring up defences against negative impacts such as extreme heat, floods and food insecurity remains a priority for African countries. Leaders at the summit made it clear in their final declaration – yet to be published – that the continent needs scaled-up, grant-based and concessional finance for adaptation, whose delivery should avoid loading countries with more debt.

Since 2017, most adaptation finance flows to the continent have come as loans, with little private sector investment, raising fears over rising debt burdens on the continent. While Africa needs about $70 billion annually for adaptation, it received only $14.8 billion in 2023, according to an analysis by the Global Center on Adaptation (GCA) and Climate Policy Initiative (CPI) released during the summit.

The analysis showed that since most adaptation finance comes from international public sources such as donor governments and multilateral development banks, cuts in bilateral aid mean capital flows to sub-Saharan Africa are projected to decline in 2025.

“Public health emergency”: Report shows fossil fuel impacts on every stage of life

Reacting to the report’s findings, Macky Sall, former president of Senegal and chair of the GCA, said the aid cuts from major donor countries would be “unprecedented – and unacceptable – precisely when resilience spending must rise”.

To enable African countries to build resilient infrastructure without piling on unsustainable debt, Sall called on developed-country partners “to reverse planned reductions, ring-fence adaptation within aid budgets, and expand guarantees and local-currency facilities”.

Tadeous Chifamba, permanent secretary of environment, climate and wildlife in Zimbabwe, said COP30 should focus attention on increasing adaptation finance flows to Africa, drive a restructuring of the global financial architecture and ensure developed countries, which are responsible for historical emissions, play their part in mobilising funds for adaptation.

“It has become a moral obligation on their part to ensure that there is fairness, justice and that they assume responsibility just as we are doing as the first-line defenders,” Chifamba told an event on the sidelines of the Addis summit.

Mobilising African money too

While African leaders need developed countries to help deliver finance for adaptation, they made it clear at the summit that the continent is not asking for charity, but is championing local solutions and will also mobilise resources from African financial institutions to respond to climate shocks.

At the summit, the second phase of the Africa-led Adaptation Acceleration Program (AAAP)- a joint initiative of the African Development Bank and the GCA – was launched with a goal to mobilise $50 billion by 2030 to climate-proof Africa and build resilience in different sectors including agriculture, infrastructure, food systems and urban areas, as well as creating jobs.

This is a boost to the program’s initial target of $25 billion and will be achieved through a convergence of private-sector leadership, innovation and resilient economic growth, according to the GCA.

COP observers invited to reveal who is bank-rolling their participation at climate talks

Bernadette Arakwiye, Rwanda’s environment minister, told the summit that Africa needs to shift from a position of deficit to opportunity, and start leveraging its assets by unlocking domestic capital. “Africa’s financial institutions hold trillions in assets and yet only a fraction is flowing to climate resilience – we need to change this,” she added.

Investing for resilient growth

Unlocking private finance would scale up adaptation investments to equip countries to quickly respond to climate shocks, Arakwiye emphasised, adding that private capital can move the continent away from small and fragmented initiatives to large-scale bankable projects.

The Baku-to-Belém Roadmap for boosting climate finance to $1.3 trillion a year by 2035, to be presented at COP30, will go some way in showing how more funds can be raised for adaptation, including through multilateral development banks, private investment and country platforms for investment, Melanie Robinson, global climate director at the World Resources Institute (WRI), told journalists this week.

Comment: How COP30 could deliver an ambitious outcome on global finance flows

Citing WRI’s research, she noted that every dollar invested in adaptation can generate more than ten times its value in economic, social and environmental benefits.

In addition to finance, policy and regulatory changes such as insurance systems, land zoning and business incentives are also needed to support adaptation on the ground, she said.

“COP30 will be an opportunity to focus more on adaptation and resilience – and this is about investing, not just to save lives, although that’s very important, but actually to drive resilient growth and enable communities and businesses to thrive in a changing climate,” she added.

The post Can COP30 turn adaptation talks into real-world investments? appeared first on Climate Home News.

Can COP30 turn adaptation talks into real-world investments?

Climate Change

North Carolina Regulators Nix $1.2 Billion Federal Proposal to Dredge Wilmington Harbor

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers failed to explain how it would mitigate environmental harms, including PFAS contamination.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers can’t dredge 28 miles of the Wilmington Harbor as planned, after North Carolina environmental regulators determined the billion-dollar proposal would be inconsistent with the state’s coastal management policies.

North Carolina Regulators Nix $1.2 Billion Federal Proposal to Dredge Wilmington Harbor

Climate Change

Australia’s renewable energy opportunity

Australia has some of the largest areas of high volume, consistent solar and wind energy anywhere in the world. It is a natural advantage that many countries in our region and across Europe will envy as they ramp up their efforts to reduce carbon pollution.

Australia has an amazing opportunity to utilise this abundance of reliable energy not only to transform our own energy systems but also that of our neighbours – if we get the policy settings right.

We are, in fact, already seeing the benefits of renewable energy flowing into our electricity grids. With all the inflation pressures on our bank accounts it looks like electricity pricing may be one cost that could be turning a corner – largely thanks to cheap solar and wind energy.

Renewables are Bringing Down the Cost of Producing Electricity

Here at Greenpeace, while we think there are some important questions to ask about renewable energy, it is clear that solar and wind are certainly the cheapest energy options available.

In contrast, coal, oil and gas are not only big on pollution, they are also proving costlier as they struggle to cope with the changing nature of our electricity systems. Plus, fossil fuels are much more exposed to international price fluctuations – as we all experienced when our electricity bills rapidly rose following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Wouldn’t it be great if we instead had energy independence, sourced from an infinite supply of clean energy?

Solar and wind (backed by batteries) can do just that and the reality is that they are already out-competing the old guard of gas and coal simply because they are quicker and cheaper to deploy. Which is good news for electricity prices!

Although whether energy retailers are passing on those savings to customers is another question. Short answer: no, they’re not – but it is a bit complex.

Why are my electricity bills still high?

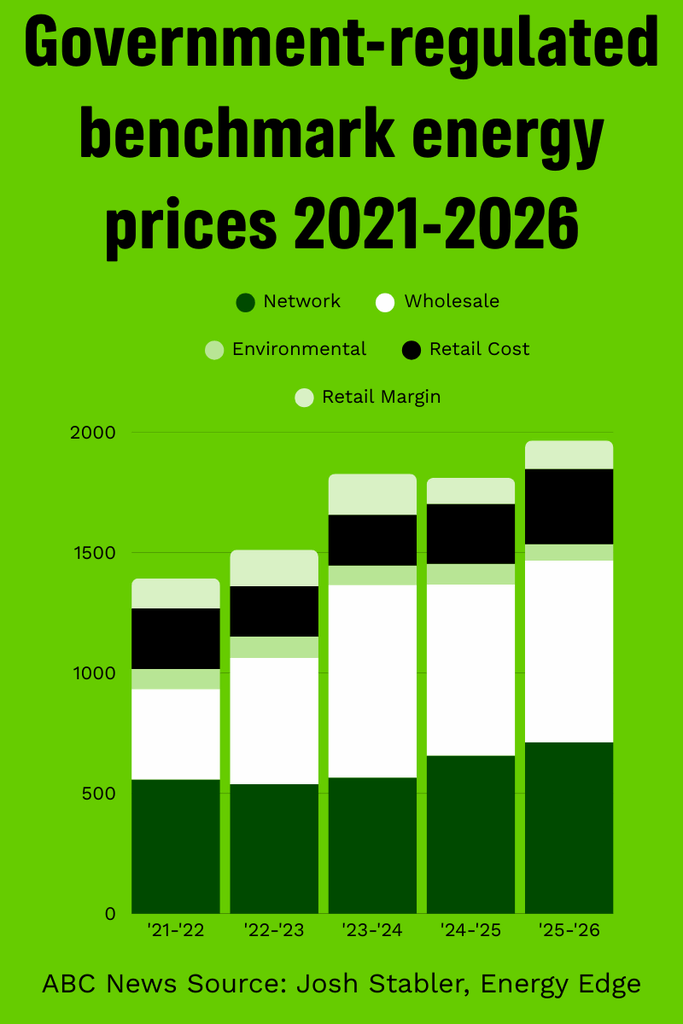

There are a number of elements that make up the final amount we see on our bills. The graph below shows the breakdown of energy costs covered by our bills.

You will see roughly a third (36.2% in 2025-26) of the cost goes to maintenance and build out of the electricity grid. This includes the transmission lines needed to connect to new renewable energy sites and to connect states so they can better share their energy resources. The ‘network’ costs have been increasing but so have other components of our bill, most notably the ‘wholesale’ cost of producing electricity.

Thankfully, the cost of producing the electricity is now starting to go down (thanks to renewables and batteries), but they are coming off record highs thanks to the exorbitant cost of gas and the unreliability of coal power stations that are old and no longer fit for purpose.

During high demand times (eg, when we all get home from work on a hot day and turn on the air conditioning) spot prices can quickly jump. Add to that a couple of coal power plants breaking down (as they increasingly do), and expensive gas fired power use spikes in the system. This can quickly cancel out any of the cost savings solar power may have created during the day when prices can actually go negative.

The good news is that this is exactly the problem batteries can solve. Batteries are great at soaking up the surplus supply of solar during the middle of the day, which creates a more efficient system, and then rapidly pumping out that power during the evening peak at a cheaper rate than gas.

How much have costs come down?

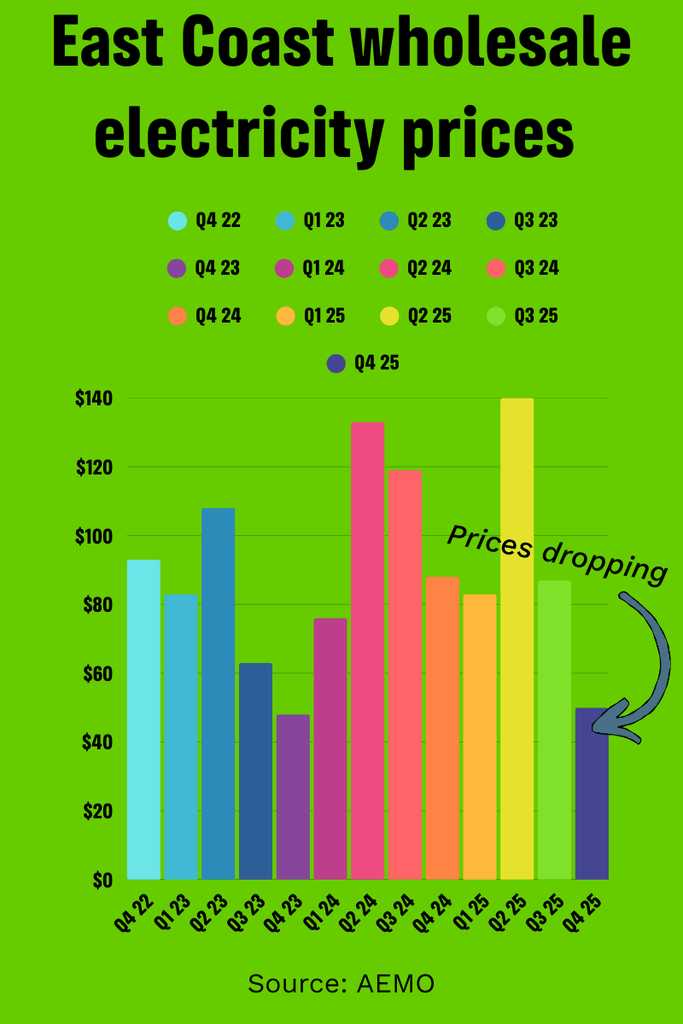

According to the Australian energy regulator (AEMO), wholesale electricity prices across the east coast have dropped by 44% when comparing prices in quarter 4 of 2025 to the same period in 2024.

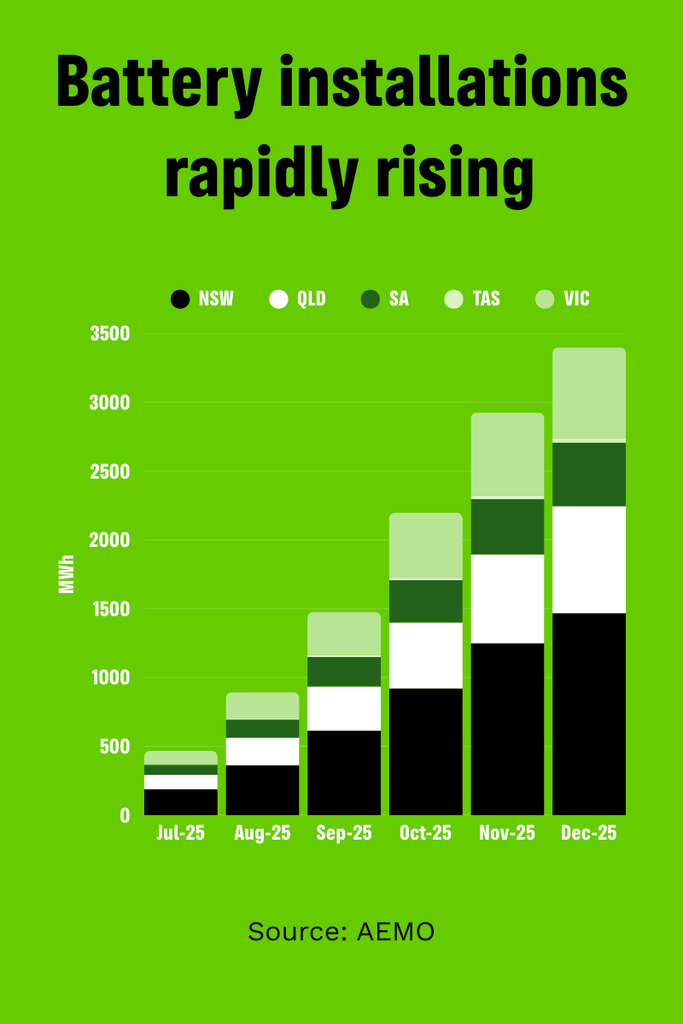

AEMO directly attributes the change to the significant growth in wind (up 29%), solar (up 15%), and batteries (3,796 MW of new battery capacity added). This influx of cheap renewable energy has seen a corresponding decrease in the use of polluting fossil fuels to power the grid. Coal fired power dropped by 4.6% and gas fired power fell by a staggering 27%.

The same trend can be seen in the world’s largest standalone grid in WA where renewable energy and storage supplied a record 52.4% of the grid’s energy across the final 3 months of 2025. That is an impressive result given there is no interstate connection to borrow energy from and there is no hydroelectric power in the system.

As a result, WA has seen a 13% drop in wholesale electricity prices thanks to a 5.8% reduction in coal fired power and a 16.4% reduction in gas fired power.

Australian Households Lead the Way on Solar and Batteries

Despite all the attempts to discredit clean energy by Trump and other conservative politicians, Aussie households have long known the value of renewable energy. In fact, Australia now holds the title for the highest rate of solar energy per capita in the world.

This is now being followed by the rapid takeup of household batteries with the Clean Energy Regulator being overwhelmed with interest in the Cheaper Home Batteries Program. They now expect to receive “around 175,000 valid battery applications corresponding to a total usable capacity of 3.9 GWh by the end of 2025.”’

All these extra batteries storing the surplus solar energy across our neighbourhoods during the day is not only creating drastic bill reductions for those households who are installing them, it is helping the whole grid. Which eventually will help everyone’s electricity bills.

If Australia as a whole follows the lead of suburban families by switching to cheap solar (plus wind) backed-up by batteries, it has an unparalleled opportunity to build its economy on the back of unlimited, local, clean energy harnessed from the sun and wind.

Powering our Future Economy

If there was ever something Australia has a natural advantage in, its sun and wind. But given the growing demand for electricity from data centres and the electrification of heavy industry, we are going to need more than just rooftop solar panels.

That’s where Australia has the potential, more than almost any other country, to become a renewable energy powerhouse and punch above our weight in the fight against climate change. See for example the unique opportunity to enter into the production and export of green iron.

While there is still quite a way to go before our electricity is fully sourced from solar and wind, we are well on the way. The clean energy charge is gathering pace – and our communities, oceans, wildlife and bank balances will be the better for it.

Climate Change

Whale Entanglements in Fishing Gear Surge Off U.S. West Coast During Marine Heatwaves

New research finds that rising ocean temperatures are shrinking cool-water feeding grounds, pushing humpbacks into gear-heavy waters near shore. Scientists say ocean forecasting tool could help fisheries reduce the risk.

Each spring, humpback whales start to feed off the coast of California and Oregon on dense schools of anchovies, sardines and krill—prey sustained by cool, nutrient-rich water that seasonal winds draw up from the deep ocean.

Whale Entanglements in Fishing Gear Surge Off U.S. West Coast During Marine Heatwaves

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits