Mental health problems induced, in part, by climate change are becoming increasingly common as the world warms, including the number of people experiencing “ecological grief”.

Ecological grief is one of the emotional responses seen in those living with the impacts of climate change-induced extreme weather events, such as floods, droughts or heatwaves.

In addition to crop failures due to extreme weather, individuals can experience ecological grief in response to declining yields and other changes, particularly where this directly impacts their lives and livelihoods.

This is particularly true of those in the global south, who are disproportionately affected by climate change, despite historically contributing less to the problem.

In a recent study of farmers in the Upper West Region of Ghana, I looked at how the grief caused by ecological loss can manifest in multiple ways, including causing mental health and psychosocial problems ranging from emotional distress to anxiety, depression, helplessness, hopelessness and sadness.

This research shows the potential for including ecological grief and other mental health impacts in the strategies of countries – especially those in the global south – looking for ways to adapt to climate change.

What is ecological grief?

As people increasingly live with the impact of climate change, research has tried to identify the impact it has on people’s lives.

For example, people who have been exposed to life-threatening extreme climate events are at a considerable risk of developing post-traumatic stress disorder as a result. Symptoms of this include flashbacks of the event, increased reactivity and avoidance of cues to the memory of the event.

In addition to this, several new concepts for climate change-induced distress have been introduced, to describe the long-term emotional consequences of anticipated or actual environmental changes.

Ecological grief refers to the mourning of ecological losses, including loss of species, ecosystems and meaningful landscapes, often shaped by acute or chronic ecological change.

The concept explains grief experienced in response to actual or anticipated losses in the natural world. This mourning of the loss of ecosystems, landscapes, species and ways of life has become a frequent lived experience for people around the world.

In 2018, a study published in Nature provided a conceptual clarification and understanding of climate change-induced ecological grief. It highlighted the implications of climate change-induced ecological loss on the mental health and wellbeing of people, as well as how people respond to ecological change that has both direct and indirect effects on the natural environment.

Ecological grief provides a conceptual understanding of the lived experiences of people who retain close living, working and cultural relationships to the natural environment.

Most of these people depend almost exclusively on the natural environment for livelihood needs, such as smallholder farmers who live in poor communities in the global south.

Research gap

Despite the effects of climate change on people in the global south, there is a dearth of understanding of ecological grief within the context of developing countries.

As such, paying closer attention to climate change-driven ecological grief within the context of developing countries could inform the design of climate change response strategies, decision-making, policies and interventions at the local level.

My current research aims to understand the lived experiences of climate change-induced ecological grief in the Upper West Region, Ghana’s most climate-vulnerable region.

It identifies climate change-induced ecological losses and how farmers in the region emotionally respond to those losses. The work highlights different non-economic experiences of climate change effects, focusing on emotional and mental health dimensions, which remain a relatively unexplored area.

Ecological grief in Ghana

Farmers’ understanding of ecological grief revolves around their emotional response to the loss of their livelihoods. This reaffirms farmers’ strong connection to their environment, on which their livelihoods are predicated.

First, farmers grieve the loss of their crops to extreme climate events, such as floods, droughts, heatwaves and climate-induced pests. The grief associated with the loss of crops has almost become perennial, as these extreme climate events have become more frequent.

In interviews undertaken as part of the research, farmers compared the feeling of losing their crops with the emotional pain of losing a loved one.

Second, farmers grieve the disappearance of their indigenous seeds and genetic resources.

Local seeds have been replaced with drought-resistant seed varieties, which farmers are encouraged to adopt to provide resilience in the face of the increasing impact of climate change.

Interview responses demonstrate that the adoption of the new seeds is causing the loss of farmers’ own seed varieties, which can be freely saved, exchanged and reused yearly. With the adoption of new seed varieties, farmers are losing their genetic resources and the culture associated with it. This is becoming a great source of worry and grief for farmers in the Upper West Region of Ghana, the research shows.

Third, farmers grieve the loss of their traditional ecological knowledge that was passed down to them by previous generations. This knowledge includes their ability to predict weather patterns, know farming seasons, determine soil types, know crop varieties and select seeds, among many other areas.

Without this knowledge system, farmers cannot practice agriculture as they have done in previous generations. The culture, values, norms and beliefs of farmers are tied to their traditional ecological knowledge, which often manifests through practice.

My research suggests that farmers are no longer able to predict weather patterns and farming seasons, an emerging trend that makes them feel as though they have lost their wisdom. This makes them worry.

Another source of grief for farmers is their inability to pass on their traditional ecological knowledge to their children, the research shows. This is because their ecological knowledge is becoming worthless as a result of climate change.

Way forward

My research explored ecological grief, an under-explored area of climate change-induced mental health problems in developing countries.

Indeed, farmers in developing countries are vulnerable to prolonged mental health problems if extreme climate events continue.

Moreover, a lack of alternative livelihoods and access to mental health services greatly increases farmers’ vulnerability to climate change-induced mental health problems.

This is compounded by a social culture that prohibits help-seeking.

Further research within these spaces would enable the design of targeted strategies and the provision of mental health services in rural areas.

The post Guest post: How climate change is causing ‘ecological grief’ for farmers in Ghana appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Guest post: How climate change is causing ‘ecological grief’ for farmers in Ghana

Climate Change

Analysis: EVs just outsold petrol cars in EU for first time ever

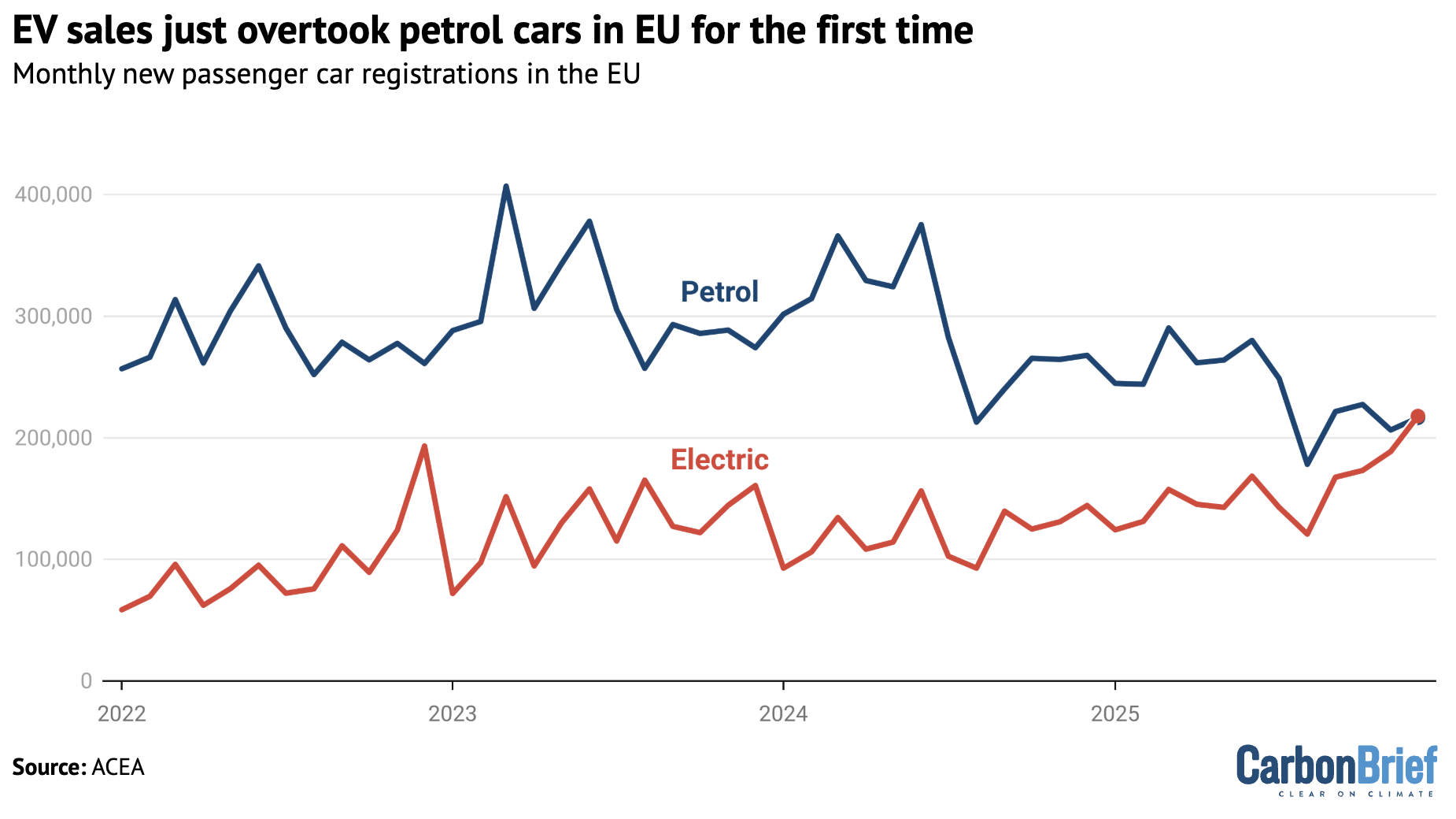

Sales of electric vehicles (EVs) overtook petrol cars in the EU for the first time in December 2025, according to new figures released by industry group the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA).

The figures show that registrations of battery EVs – sometimes referred to as BEVs, or “pure EVs” – reached 217,898, up 51% year-on-year from December 2024, as shown in the chart below.

Meanwhile, sales of petrol cars in the bloc fell 19% year-on-year, from 267,834 in December 2024 to 216,492 in December 2025.

Overall in 2025, EVs reached 17.4% of the market share in the bloc, up from 13.6% the previous year.

(EVs run purely from a battery that is charged from an external source, plug-in hybrids have both a battery that can be charged and an internal combustion engine, whilst regular hybrids cannot be plugged in, they have a smaller battery that is charged from the engine or braking.)

According to ACEA, 1,880,370 new battery-electric cars were registered last year, with the four biggest markets – Germany (+43.2%), the Netherlands (+18.1%), Belgium (+12.6%), and France (+12.5%) – accounting for 62% of registrations.

In a release setting out the figures, ACEA described this as “still a level that leaves room for growth to stay on track with the transition”.

Meanwhile, registrations of petrol cars fell by 18.7% across 2025, with all major markets seeing a decrease.

France accounted for the steepest decline in petrol registrations at 32% year-on-year, followed by Germany (-21.6%), Italy (-18.2%), and Spain (-16%).

Overall, 2,880,298 new petrol cars were registered in 2025, a drop in market share from 33.3% in December 2024 to 26.6%.

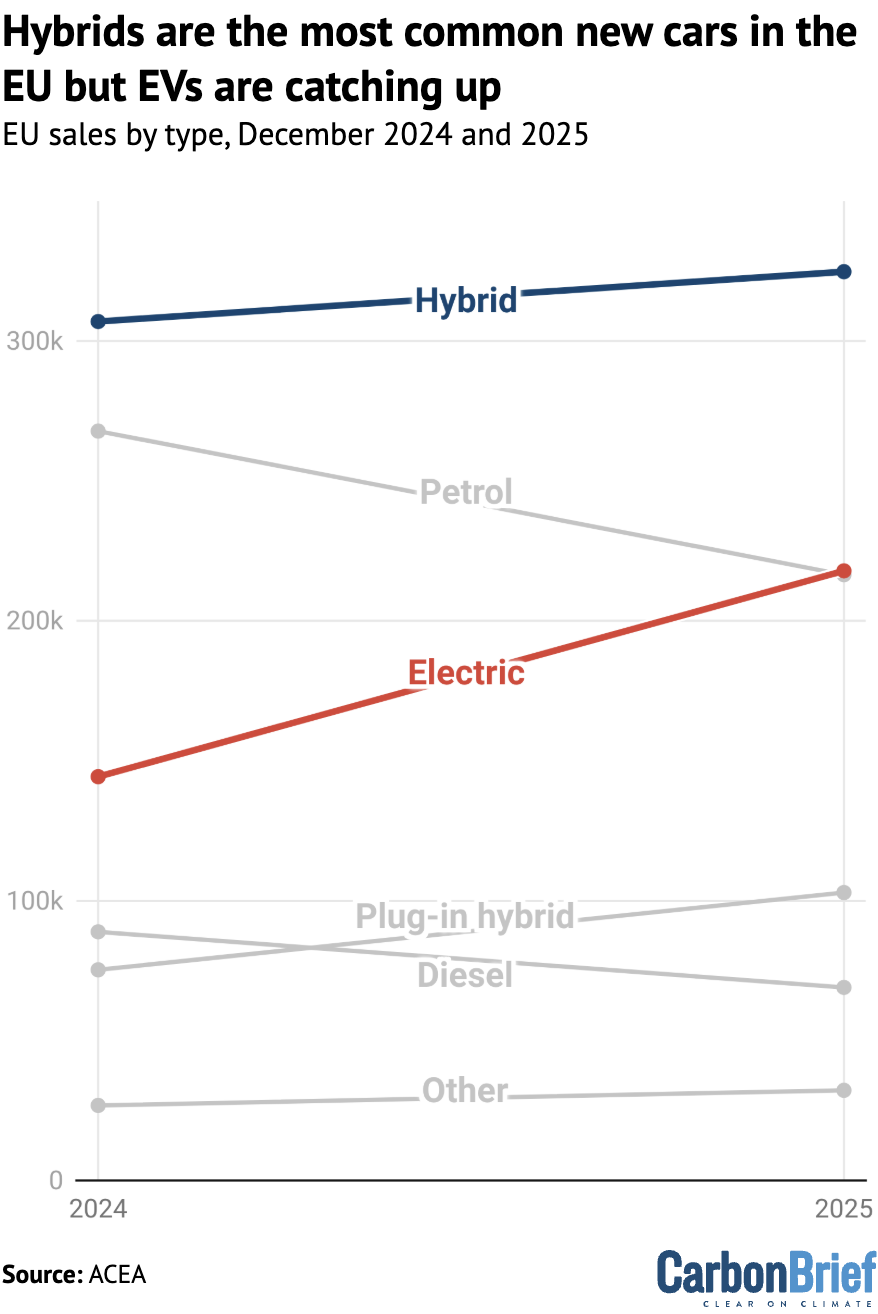

Hybrid vehicles, which are entirely fuelled by petrol or diesel, remain the largest segment of the EU car market, with sales jumping 5.8% from 307,001 in December 2024 to 324,799 a year later, as shown in the chart below.

However, cars that can run on electricity – battery EVs and plug-in hybrids – are growing even faster, with sales up 51% and 36.7% in December 2025, respectively.

The registration figures follow the EU’s automotive package, released in December to “support the automotive sector’s efforts in the transition to clean mobility”.

It includes a proposed shift from banning the sale of new combustion-engine cars from 2035 to reducing their tailpipe emissions.

Under the proposals, the EU will target a 90% cut in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from 2021 levels by 2035, rather than all vehicle sales having to be zero-emissions.

If approved, the package would require that the remaining 10% of emissions be compensated through the use of low-carbon steel made in the EU or from e-fuels and biofuels.

This would allow for plug-in hybrids (PHEVs), “range extenders”, hybrids and pure internal combustion engine vehicles to “still play a role beyond 2035”.

There has been repeated pushback from the automotive sector in Europe against the introduction of “clean car rules”, which has led to targets being shifted more than once.

For example, the head of Stellantis, one of the largest car manufacturers in Europe, recently claimed that there was no “natural” demand for EVs.

Automakers have argued that EU targets for cleaner cars should be eased in the face of competition from Chinese producers and US tariffs.

ACEA figures show Volkswagen continued to claim the largest market share in the EU, accounting for 26.7% of new registrations in December, up from 25.6% a year earlier.

It was followed by Stellantis, Renault, Hyundai, Toyota and BMW.

EV giant Tesla saw its market share drop from 3.5% in December 2024 to 2.2% in December 2025. Over the course of 2025, the brand saw its market share in the EU fall 37.9% from 2024, following controversy around its owner, Elon Musk.

Meanwhile, Chinese EV brand BYD tripled its market share from 0.7% in December 2024 to 1.9% in December 2025.

The post Analysis: EVs just outsold petrol cars in EU for first time ever appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: EVs just outsold petrol cars in EU for first time ever

Climate Change

For proof of the energy transition’s resilience, look at what it’s up against

Al-Karim Govindji is the global head of public affairs for energy systems at DNV, an independent assurance and risk management provider, operating in more than 100 countries.

Optimism that this year may be less eventful than those that have preceded it have already been dealt a big blow – and we’re just weeks into 2026. Events in Venezuela, protests in Iran and a potential diplomatic crisis over Greenland all spell a continuation of the unpredictability that has now become the norm.

As is so often the case, it is impossible to separate energy and the industry that provides it from the geopolitical incidents shaping the future. Increasingly we hear the phrase ‘the past is a foreign country’, but for those working in oil and gas, offshore wind, and everything in between, this sentiment rings truer every day. More than 10 years on from the signing of the Paris Agreement, the sector and the world around it is unrecognisable.

The decade has, to date, been defined by a gritty reality – geopolitical friction, trade barriers and shifting domestic priorities – and amidst policy reversals in major economies, it is tempting to conclude that the transition is stalling.

Truth, however, is so often found in the numbers – and DNV’s Energy Transition Outlook 2025 should act as a tonic for those feeling downhearted about the state of play.

While the transition is becoming more fragmented and slower than required, it is being propelled by a new, powerful logic found at the intersection between national energy security and unbeatable renewable economics.

A diverging global trajectory

The transition is no longer a single, uniform movement; rather, we are seeing a widening “execution gap” between mature technologies and those still finding their feet. Driven by China’s massive industrial scaling, solar PV, onshore wind and battery storage have reached a price point where they are virtually unstoppable.

These variable renewables are projected to account for 32% of global power by 2030, surging to over half of the world’s electricity by 2040. This shift signals the end of coal and gas dominance, with the fossil fuel share of the power sector expected to collapse from 59% today to just 4% by 2060.

Conversely, technologies that require heavy subsidies or consistent long-term policy, the likes of hydrogen derivatives (ammonia and methanol), floating wind and carbon capture, are struggling to gain traction.

Our forecast for hydrogen’s share in the 2050 energy mix has been downgraded from 4.8% to 3.5% over the last three years, as large-scale commercialisation for these “hard-to-abate” solutions is pushed back into the 2040s.

Regional friction and the security paradigm

Policy volatility remains a significant risk to transition timelines across the globe, most notably in North America. Recently we have seen the US pivot its policy to favour fossil fuel promotion, something that is only likely to increase under the current administration.

Invariably this creates measurable drag, with our research suggesting the region will emit 500-1,000 Mt more CO₂ annually through 2050 than previously projected.

China, conversely, continues to shatter energy transition records, installing over half of the world’s solar and 60% of its wind capacity.

In Europe and Asia, energy policy is increasingly viewed through the lens of sovereignty; renewables are no longer just ‘green’, they are ‘domestic’, ‘indigenous’, ‘homegrown’. They offer a way to reduce reliance on volatile international fuel markets and protect industrial competitiveness.

Grids and the AI variable

As we move toward a future where electricity’s share of energy demand doubles to 43% by 2060, we are hitting a physical wall, namely the power grid.

In Europe, this ‘gridlock’ is already a much-discussed issue and without faster infrastructure expansion, wind and solar deployment will be constrained by 8% and 16% respectively by 2035.

Comment: To break its coal habit, China should look to California’s progress on batteries

This pressure is compounded by the rise of Artificial Intelligence (AI). While AI will represent only 3% of global electricity use by 2040, its concentration in North American data centres means it will consume a staggering 12% of the region’s power demand.

This localized hunger for power threatens to slow the retirement of fossil fuel plants as utilities struggle to meet surging base-load requirements.

The offshore resurgence

Despite recent headlines regarding supply chain inflation and project cancellations, the long-term outlook for offshore energy remains robust.

We anticipate a strong resurgence post-2030 as costs stabilise and supply chains mature, positioning offshore wind as a central pillar of energy-secure systems.

Governments defend clean energy transition as US snubs renewables agency

A new trend is also emerging in behind-the-meter offshore power, where hybrid floating platforms that combine wind and solar will power subsea operations and maritime hubs, effectively bypassing grid bottlenecks while decarbonising oil and gas infrastructure.

2.2C – a reality check

Global CO₂ emissions are finally expected to have peaked in 2025, but the descent will be gradual.

On our current path, the 1.5C carbon budget will be exhausted by 2029, leading the world toward 2.2C of warming by the end of the century.

Still, the transition is not failing – but it is changing shape, moving away from a policy-led “green dream” toward a market-led “industrial reality”.

For the ocean and energy sectors, the strategy for the next decade is clear. Scale the technologies that are winning today, aggressively unblock the infrastructure bottlenecks of tomorrow, and plan for a future that will, once again, look wholly different.

The post For proof of the energy transition’s resilience, look at what it’s up against appeared first on Climate Home News.

For proof of the energy transition’s resilience, look at what it’s up against

Climate Change

Post-COP 30 Modeling Shows World Is Far Off Track for Climate Goals

A new MIT Global Change Outlook finds current climate policies and economic indicators put the world on track for dangerous warming.

After yet another international climate summit ended last fall without binding commitments to phase out fossil fuels, a leading global climate model is offering a stark forecast for the decades ahead.

Post-COP 30 Modeling Shows World Is Far Off Track for Climate Goals

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits