President Xi Jinping has personally pledged to cut China’s greenhouse gas emissions to 7-10% below peak levels by 2035, while “striving to do better”.

This is China’s third pledge under the Paris Agreement, but is the first to put firm constraints on the country’s emissions by setting an “absolute” target to reduce them.

China’s leader spoke via video to a UN climate summit in New York organised by secretary general António Guterres, making comments seen as a “veiled swipe” at US president Donald Trump.

The headline target, with its undefined peak-year baseline, falls “far short” of what would have been needed to help limit warming to well-below 2C or 1.5C, according to experts.

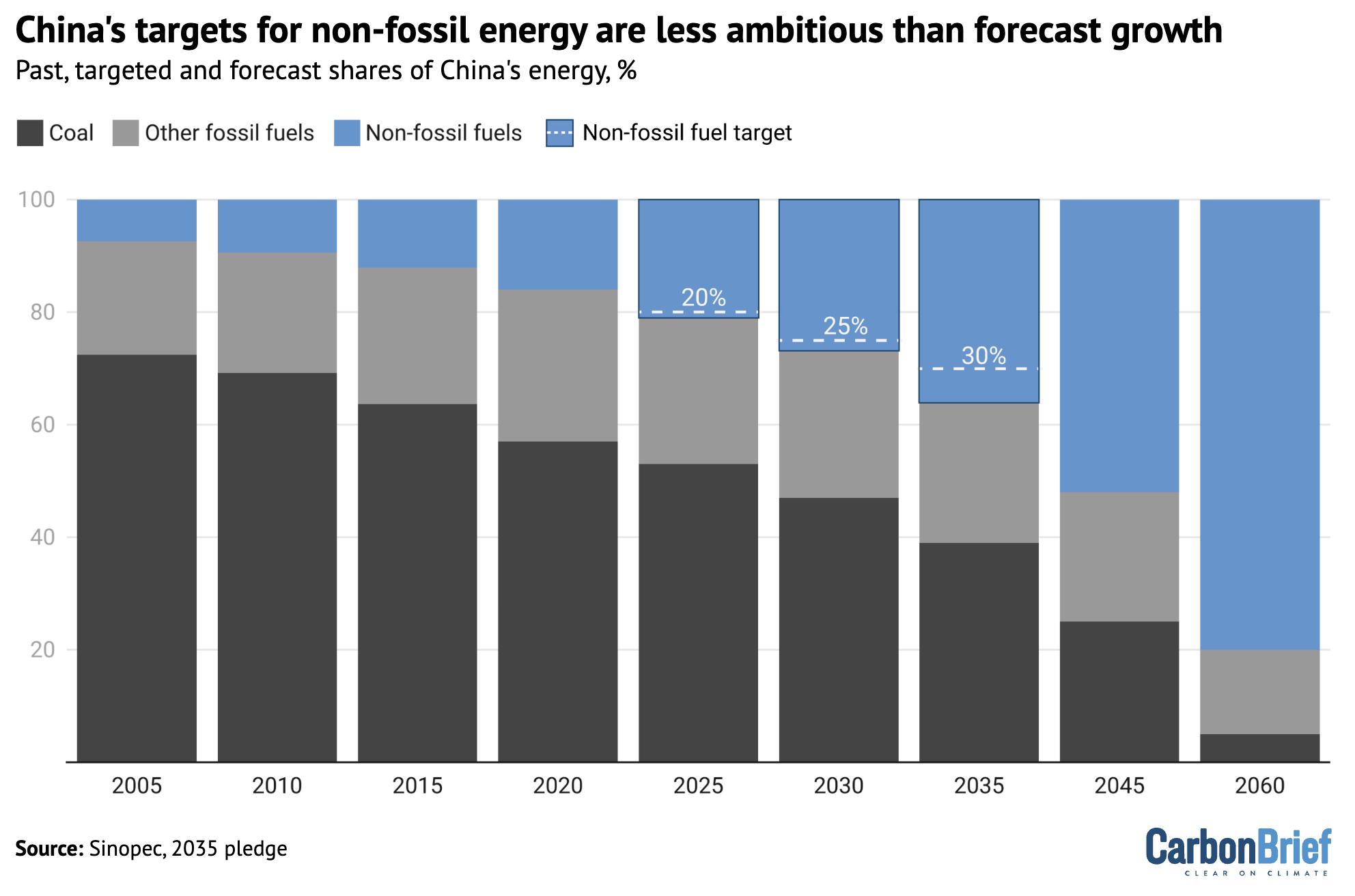

Moreover, Xi’s pledge for non-fossil fuels to make up 30% of China’s energy is far below the latest forecasts, while his goal for wind and solar capacity to reach 3,600 gigawatts (GW) implies a significant slowdown, relative to recent growth.

Overall, the targets for China’s new 2035 “nationally determined contribution” (NDC) under the Paris Agreement have received a lukewarm response, described as “conservative”, “too weak” and as not reflecting the pace of clean-energy expansion on the ground.

Nevertheless, Li Shuo, director of the China Climate Hub at the Asia Society Policy Institute (ASPI), tells Carbon Brief that the pledge marks a “big psychological jump for the Chinese”, shifting from targets that constrained emissions growth to a requirement to cut them.

Below, Carbon Brief unpacks what China’s new targets mean for its emissions and energy use, pending further details once its full NDC is formally published in full.

Carbon Brief is hosting a webinar about China’s new climate goals on Monday. Register here.

- What is in China’s new climate pledge?

- What is China’s first ‘absolute’ emissions reduction target?

- What has China pledged on non-fossil energy, coal and renewables?

- What does China say about non-CO2 emissions?

What is in China’s new climate pledge?

For now, the only available information on China’s 2035 NDC is the short series of pledges in Xi’s speech to the UN.

(This article will be updated once the NDC itself is published on the UN’s website.)

Xi’s speech is the first time his country has promised to place an absolute limit on its greenhouse gas emissions, marking a significant shift in approach.

Xi had previously pledged that China would peak its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions “before 2030”, without defining at what level, reaching “carbon neutrality” by 2060.

He also outlined a handful of other key targets for 2035, shown in the table below against the goals set in previous NDCs.

| Indicators | Targets for 2035 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| First NDC (2016) | NDC 2.0 (2021) | NDC 3.0 (2025) | |

| Emissions target | Peak CO2 “around 2030”, “making best efforts to peak early” | Peak CO2 “before 2030” and “achieve carbon neutrality before 2060” | Cut GHGs to 7-10% below peak levels by 2035 |

| CO2 intensity reduction (compared to 2005) | 60-65% | >65% | – |

| Non-fossil share in primary energy mix | Around 20% | Around 25% | 30% |

| Forest stock volume increase (compared to 2005) | Around 4.5bn cubic metres | 6bn cubic metres | 11bn cubic metres |

| Installed capacity of wind and solar power | – | >1,200GW | >3,600GW |

In his speech, Xi also said that, by 2035, “new energy vehicles” would be the “mainstream” for new vehicle sales, China’s national carbon market would cover all “major high-emission industries” and that a “climate-adaptive society” would be “basically established”.

This is the first time that China’s targets will cover the entire economy and all greenhouse gases (GHGs), a move that has been long signalled by Chinese policymakers.

In 2023, the joint China-US Sunnylands statement, released during the Biden administration, had said that both countries’ 2035 NDCs “will be economy-wide, include all GHGs and reflect…[the goal of] holding the increase in global average temperature to well-below 2C”.

Subsequently, the world’s first global stocktake, issued at COP28 in Dubai, “encourage[d]” all countries to submit “ambitious, economy-wide emission reduction targets, covering all GHGs, sectors and categories…aligned with limiting global warming to 1.5C”.

Responding to this the following year, executive vice-premier and climate lead Ding Xuexiang stated at COP29 in Baku that China’s 2035 climate pledge would be economy-wide and cover all GHGs. (His remarks did not mention alignment with 1.5C.)

This was reiterated by Xi at a climate meeting between world leaders in April 2025.

The absolute target for all greenhouse gases marks a turning point in China’s emissions strategy. Until now, China’s emissions targets have largely focused on carbon intensity, the emissions per unit of GDP, a metric that does not directly constrain emissions as a whole.

The change aligns with China’s broader shift from “dual control of energy” towards “dual control of carbon”, a policy that replaces China’s current tradition of setting targets for energy intensity and total energy consumption, with carbon intensity and carbon emissions.

Under the policy, in the 15th five-year plan period (2026-2030), China will continue to centre carbon intensity as its main metric for emissions reduction. After 2030, an absolute cap on carbon emissions will become the predominant target.

What is China’s first ‘absolute’ emissions reduction target?

In his UN address, Xi pledged to cut China’s “economy-wide net greenhouse gas emissions” to 7-10% below peak levels by 2035, while “striving to do better”.

This means the target includes not just CO2, but also methane, nitrous oxide (N2O) and F-gases, all of which make significant contributions to global warming. (See: What does China say about non-CO2 emissions?)

The reference to “economy-wide net” emissions means that the target refers to the total of China’s emissions, from all sources, minus removals, which could come from natural sources, such as afforestation, or via “carbon dioxide removal” technologies.

Outlining the targets, Xi told the UN summit that they represented China’s “best efforts, based on the requirements of the Paris Agreement”. He added:

“Meeting these targets requires both painstaking efforts by China itself and a supportive and open international environment. We have the resolve and confidence to deliver on our commitments.”

China has a reputation for under-promising and over-delivering.

Prof Wang Zhongying, director-general of the Energy Research Institute, a Chinese government-affilitated thinktank, told Carbon Brief in an interview at COP26 that China’s policy targets represent a “bottom line”, which the policymakers are “definitely certain” about meeting. He views this as a “cultural difference”, relative to other countries.

The headline target announced by Xi this week has, nevertheless, been seen as falling far short of what was needed.

A series of experts had previously told Carbon Brief that a 30% reduction from 2023 levels was the absolute minimum contribution towards a 1.5C global limit, with many pointing to much larger reductions in order to be fully aligned with the 1.5C target.

The figure below illustrates how China’s 2035 target stacks up against these levels.

(Note that the timing and level of peak emissions is not defined by China’s targets. The pledge trajectory is constrained by China’s previous targets for carbon intensity and expected GDP growth, as well as the newly announced 7-10% range. It is based on total emissions, excluding removals, which are more uncertain.)

Analysis by the Asia Society Policy Institute also found that China’s GHG emissions “must be reduced by at least 30% from the peak through 2035” in order to align with 1.5C warming.

It said that this level of ambition was achievable, due to China’s rapid clean-energy buildout and signs that the nation’s emissions may have already reached a peak.

Similarly, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said last October that implementing the collective goals of the first stocktake – such as tripling renewables by 2030 – as well as aligning near-term efforts with long-term net-zero targets, implied emissions cuts of 35-60% by 2035 for emerging market economies, a grouping that includes China.

In response to these sorts of numbers, Teng Fei, deputy director of Tsinghua University’s Institute of Energy, Environment and Economy, previously described a 30% by 2035 target as “extreme”, telling Agence France-Presse that this would be “too ambitious to be achievable”, given uncertainties around China’s current development trajectory.

In contrast, a January 2025 academic study, co-authored by researchers from Chinese government institutions and top universities and understood to have been influential in Beijing’s thinking, argued for a pledge to cut energy-related CO2 emissions “by about 10% compared with 2030”, estimating that emissions would peak “between 2028 and 2029”.

(Other assessments have pegged relevant indicators, such as emissions and coal consumption, as peaking in 2028 at the earliest.)

The relatively modest emissions reduction range pledged by Xi, as well as the uncertainty introduced by avoiding a definitive baseline year, has disappointed analysts.

In a note responding to Xi’s pledges, Li Shuo and his ASPI colleague Kate Logan write that he has “misse[d] a chance at leadership”.

Li tells Carbon Brief that factors behind the modest target include the “domestic economic slowdown and uncertain economic prospects, the weakening global climate momentum and the turbulent geopolitical environment”. He adds:

“I also think it is a big psychological jump for the Chinese, shifting for the first time after decades of rapid growth, from essentially climate targets that meant to contain further increase to all of a sudden a target that forces emissions to go down.”

Instead of a target consistent with limiting warming to 1.5C, China’s 2035 pledge is more closely aligned with 3C of warming, according to analysis by CREA’s Lauri Myllyirta.

Climate Action Tracker says that China’s target is “unlikely to drive down emissions”, because it was already set to achieve similar reductions under current policies.

What has China pledged on non-fossil energy, coal and renewables?

In addition to a headline emissions reduction target, Xi also pledged to expand non-fossil fuels as a share of China’s energy mix and to continue the rollout of wind and solar power.

This continues the trend in China’s previous NDC.

Notably, however, Xi made no mention of efforts to control coal in his speech.

In its second NDC, focused on 2030, China had pledged to “strictly control coal-fired power generation projects”, as well as “strictly limit” coal consumption between 2021-2025 and “phase it down” between 2026-2030. It also said China “will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad”.

It remains to be seen if coal is addressed in China’s full NDC for 2035.

The 2030 NDC also stated that China would “increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 25%” – and Xi has updated this to 30% by 2035.

These targets are shown in the figure below, alongside recent forecasts from the Sinopec Economics and Development Research Institute, which estimated that non-fossil fuel energy could account for 27% of primary energy consumption in 2030 and 36% in 2035.

As such, China’s targets for non-fossil energy are less ambitious than the levels implied by current expectations for growth in low-carbon sources.

In a recent meeting with the National People’s Congress Standing Committee – the highest body of China’s state legislature – environment minister Huang Runqiu said that progress on China’s earlier target for increasing non-fossil energy’s share of energy consumption was “broadly in line” with the “expected pace” of the 2030 NDC.

On wind and solar, China’s 2030 NDC had pledged to raise installed capacity to more than 1,200GW – a target that analysts at the time told Carbon Brief was likely to be beaten. It was duly met six years early, with capacity standing at 1,680GW as of the end of July 2025.

Xi has set a 2035 target of reaching 3,600GW of wind and solar capacity.

This looks ambitious, relative to other countries and global capacity of around 3,000GW in total as of 2024, but represents a significant slowdown from the recent pace of growth.

Given its current capacity, China would need to install around 200GW of new wind and solar per year and 2,000GW in total to reach the 2035 target. Yet it installed 360GW in 2024 and 212GW of solar alone in the first half of this year.

Myllyvirta tells Carbon Brief this pace of additions is “not enough to even peak emissions [in the power sector] unless energy demand growth slows significantly”.

While the pace of demand growth is a key uncertainty, a recent study by Michael R Davidson, associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, with colleagues at Tsinghua University, suggested that deploying 2,910-3,800GW of wind and solar by 2035 would be consistent with a 2C warming pathway.

Davidson tells Carbon Brief that “most experts within China do not see the [recent] 300+GW per year growth as sustainable”. Still, he adds that the lower levels outlined in his study could be consistent with cutting power-sector emissions 40% by 2035, subject to caveats around whether new capacity is well-sited and appropriately integrated:

“We found that 40% emissions reductions in the power sector can be supported by 3,000-3,800GW wind and solar capacity [by 2035]. Most of the capacity modeling really depends on integration and quality of resources.”

Renewable energy’s share of consumption in China has lagged behind its record capacity installations, largely due to challenges with updating grid infrastructure and economic incentives that lock in coal-fired power.

In Davidson’s study, capacity growth of up to 3,800GW would see wind and solar reaching around 40% of total power generation by 2030 and 50% by 2035.

Meanwhile, China will need to install around 10,000GW of wind and solar capacity to reach carbon neutrality by 2060, according to a separate report by the Energy Research Institute, a Chinese government-affilitated thinktank.

What does China say about non-CO2 emissions?

This is the first time that one of China’s NDC pledges has explicitly covered the emissions from non-CO2 GHGs.

However, while Xi’s speech made clear that China’s headline emissions goal for 2035 will cover non-CO2 gases, such as methane, nitrous oxide and F-gases, he did not give further details on whether the NDC would set specific targets for these emissions.

In China’s 2030 NDC, the country stated it would “step up the control of key non-CO2 GHG emissions”, including through new control policies, but did not include a quantitative emissions reduction target.

In preparation for a comprehensive greenhouse gas emissions target, China has issued action plans for methane, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs, one type of F-gas) and nitrous oxide.

The nitrous oxide action plan, published earlier this month, called for emissions per unit of production for specific chemicals to decrease to a “world-leading level” by 2030, but did not set overarching limits.

Similarly, the overarching methane action plan, issued in late 2023, listed several key tasks for reducing emissions in the energy, agriculture and waste sectors, but lacked numerical targets for emissions reduction.

A subsequent rule change in December 2024 tightened waste gas requirements for coal mines. Under the new rules, Reuters reports, any coal mine that releases “emissions with methane content of 8% or higher” must capture the gas, and either use or destroy it – down from a previous threshold of 30%.

But analysts believe that the true challenge of coal-mine methane emissions may come from abandoned mines, which, one study found, have surged in the past 10 years and will likely overtake emissions from active coal mines to become the prime source of methane emissions in the coal sector.

As the demand for coal could be facing a “structural decline”, the number of abandoned mines is expected to grow significantly.

Meanwhile, the HFC plan did set quantitative targets. The country aims to lower HFC production by 2029 by 10% from a 2024 baseline of 2GtCO2e, while consumption would also be reduced 10% from a baseline of 0.9gtCO2e in this timeframe – in line with China’s obligations under the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol on ozone protection.

From 2026, China will “prohibit” the production of fridges and freezers using HFC refrigerants.

However, the action plan does not govern China’s exports of products that use HFCs – a significant source of emissions.

The post Q&A: What does China’s new Paris Agreement pledge mean for climate action? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: What does China’s new Paris Agreement pledge mean for climate action?

Greenhouse Gases

Analysis: Half of nations meet UN deadline for nature-loss reporting

Half of nations have met a UN deadline to report on how they are tackling nature loss within their borders, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

This includes 11 of the 17 “megadiverse nations”, countries that account for 70% of Earth’s biodiversity.

It also includes all of the G7 nations apart from the US, which is not part of the world’s nature treaty.

All 196 countries that are part of the UN biodiversity treaty were due to submit their seventh “national reports” by 28 February, of which 98 have done so.

Their submissions are supposed to provide key information for an upcoming global report on actions to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030, in addition to a global review of progress due to be conducted by countries at the COP17 nature summit in Armenia in October this year.

At biodiversity talks in Rome in February, UN officials said that national reports submitted late will not be included in the global report due to a lack of time, but could still be considered in the global review.

Tracking nature action

In 2022, nations signed a landmark deal to halt and reverse nature loss by 2030, known as the “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework” (GBF).

In an effort to make sure countries take action at the domestic level, the GBF included an “implementation schedule”, involving the publishing of new national plans in 2024 and new national reports in 2026.

The two sets of documents were to inform both a global report and a global review, to be conducted by countries at COP17 in Armenia later this year. (This schedule mirrors the one set out for tackling climate change under the Paris Agreement.)

The deadline for nations’ seventh national reports, which contain information on their progress towards meeting the 23 targets of the GBF based on a set of key indicators, was 28 February 2026.

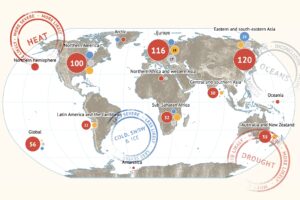

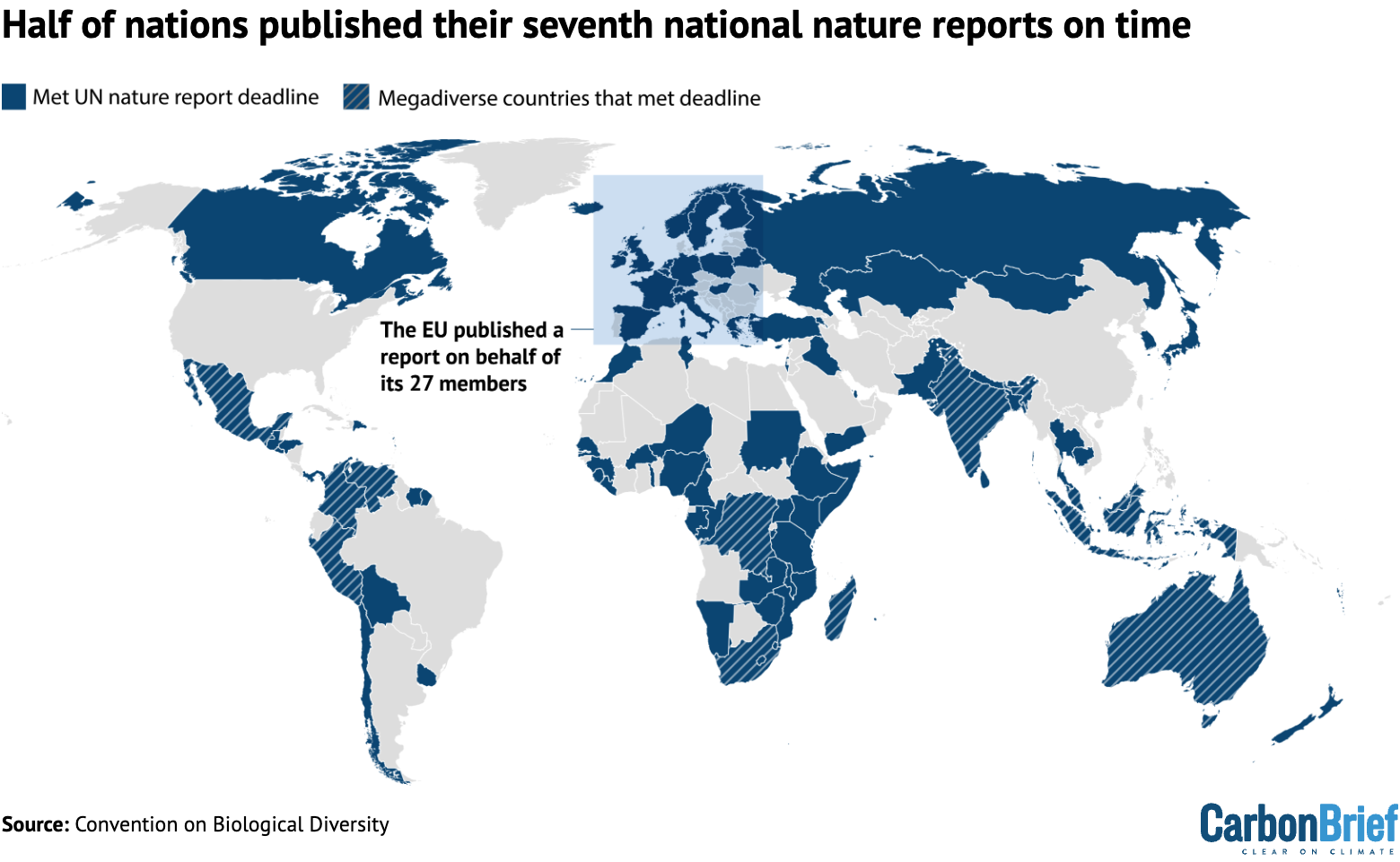

According to Carbon Brief’s analysis of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity’s online reporting platform, 98 out of the 196 countries that are part of the nature convention (50%) submitted on time.

The map below shows countries that submitted their seventh national reports by the UN’s deadline.

This includes 11 of the 17 “megadiverse nations” that account for 70% of Earth’s biodiversity.

The megadiverse nations to meet the deadline were India, Venezuela, Indonesia, Madagascar, Peru, Malaysia, South Africa, Colombia, Mexico, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Australia.

It also includes all of the G7 nations (France, Germany, the UK, Japan, Italy and Canada), excluding the US, which has never ratified the Convention on Biological Diversity.

The UK’s seventh national report shows that it is currently on track to meet just three of the GBF’s 23 targets.

This is according to a LinkedIn post from Dr David Cooper, former executive secretary of the CBD and current chair of the UK’s Joint Nature Conservation Committee, which coordinated the UK’s seventh national report,

The report shows the UK is not on track to meet one of the headline targets of the GBF, which is to protect 30% of land and sea for nature by 2030.

It reports that the proportion of land protected for nature is 7% in England, 18% in Scotland and 9% in Northern Ireland. (The figure is not given for Wales.)

National plans

In addition to the national reports, the upcoming global report and review will draw on countries’ national plans.

Countries were meant to have submitted their new national plans, known as “national biodiversity strategies and action plans” (NBSAPs), by the start of COP16 in October 2024.

A joint investigation by Carbon Brief and the Guardian found that only 15% of member countries met that deadline.

Since then, the percentage of countries that have submitted a new NBSAP has risen to 39%.

According to the GBF and its underlying documents, countries that were “not in a position” to meet the deadline to submit NBSAPs ahead of COP16 were requested to instead submit national targets. These submissions simply list biodiversity targets that countries will aim for, without an accompanying plan for how they will be achieved.

As of 2 March, 78% of nations had submitted national targets.

At biodiversity talks in Rome in February, UN officials said that national reports submitted late will not be included in the global report due to a lack of time, but could still be considered in the global review.

Funding ‘delays’

At the Rome talks, some countries raised that they had faced “difficulties in submitting [their national reports] on time”, according to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin.

Speaking on behalf of “many” countries, Fiji said that there had been “technical and financial constraints faced by parties” in the preparation of their seventh national reports.

In a statement to Carbon Brief, a spokesperson for the Global Environment Facility, the body in charge of providing financial and technical assistance to countries for the preparation of their national reports, said “delays in fund disbursement have occurred in some cases”, adding:

“In 2023, the GEF council approved support for the development of NBSAPs and the seventh national reports for all 139 eligible countries that requested assistance. This includes national grants of up to $450,000 per country and $6m in global technical assistance delivered through the UN Development Programme and UN Environment Programme.

“As of the end of January 2026, all 139 participating countries had benefited from technical assistance and 93% had accessed their national grants, with 11 countries yet to receive their funds. Delays in fund disbursement have occurred in some cases, compounded by procurement challenges and limited availability of technical expertise.”

The spokesperson added that the fund will “continue to engage closely with agencies and countries to support timely completion of NBSAPs and the seventh national reports”.

The post Analysis: Half of nations meet UN deadline for nature-loss reporting appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Half of nations meet UN deadline for nature-loss reporting

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Absolute State of the Union

‘DRILL, BABY’: US president Donald Trump “doubled down on his ‘drill, baby, drill’ agenda” in his State of the Union (SOTU) address, said the Los Angeles Times. He “tout[ed] his support of the fossil-fuel industry and renew[ed] his focus on electricity affordability”, reported the Financial Times. Trump also attacked the “green new scam”, noted Carbon Brief’s SOTU tracker.

COAL REPRIEVE: Earlier in the week, the Trump administration had watered down limits on mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants, reported the Financial Times. It remains “unclear” if this will be enough to prevent the decline of coal power, said Bloomberg, in the face of lower-cost gas and renewables. Reuters noted that US coal plants are “ageing”.

OIL STAY: The US Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments brought by the oil industry in a “major lawsuit”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper said the firms are attempting to head off dozens of other lawsuits at state level, relating to their role in global warming.

SHIP-SHILLING: The Trump administration is working to “kill” a global carbon levy on shipping “permanently”, reported Politico, after succeeding in delaying the measure late last year. The Guardian said US “bullying” could be “paying off”, after Panama signalled it was reversing its support for the levy in a proposal submitted to the UN shipping body.

Around the world

- RARE EARTHS: The governments of Brazil and India signed a deal on rare earths, said the Times of India, as well as agreeing to collaborate on renewable energy.

- HEAT ROLLBACK: German homes will be allowed to continue installing gas and oil heating, under watered-down government plans covered by Clean Energy Wire.

- BRAZIL FLOODS: At least 53 people died in floods in the state of Minas Gerais, after some areas saw 170mm of rain in a few hours, reported CNN Brasil.

- ITALY’S ATTACK: Italy is calling for the EU to “suspend” its emissions trading system (ETS) ahead of a review later this year, said Politico.

- COOKSTOVE CREDITS: The first-ever carbon credits under the Paris Agreement have been issued to a cookstove project in Myanmar, said Climate Home News.

- SAUDI SOLAR: Turkey has signed a “major” solar deal that will see Saudi firm ACWA building 2 gigawatts in the country, according to Agence France-Presse.

$467 billion

The profits made by five major oil firms since prices spiked following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine four years ago, according to a report by Global Witness covered by BusinessGreen.

Latest climate research

- Claims about the “fingerprint” of human-caused climate change, made in a recent US Department of Energy report, are “factually incorrect” | AGU Advances

- Large lakes in the Congo Basin are releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere from “immense ancient stores” | Nature Geoscience

- Shared Socioeconomic Pathways – scenarios used regularly in climate modelling – underrepresent “narratives explicitly centring on democratic principles such as participation, accountability and justice” | npj Climate Action

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

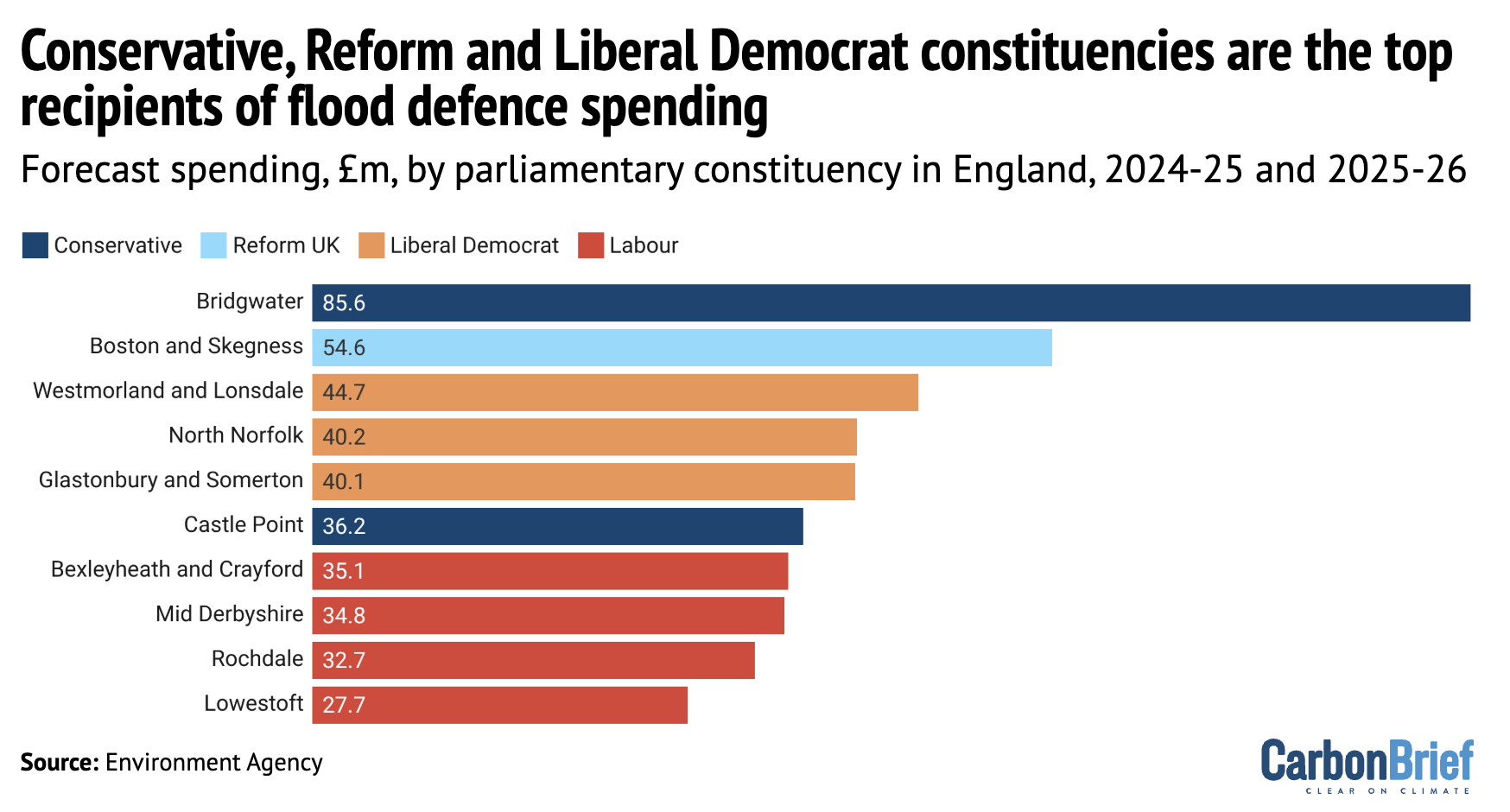

The constituency of Richard Tice MP, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of Reform UK, is the second-largest recipient of flood defence spending in England, according to new Carbon Brief analysis. Overall, the funding is disproportionately targeted at coastal and urban areas, many of which have Conservative or Liberal Democrat MPs.

Spotlight

Is there really a UK ‘greenlash’?

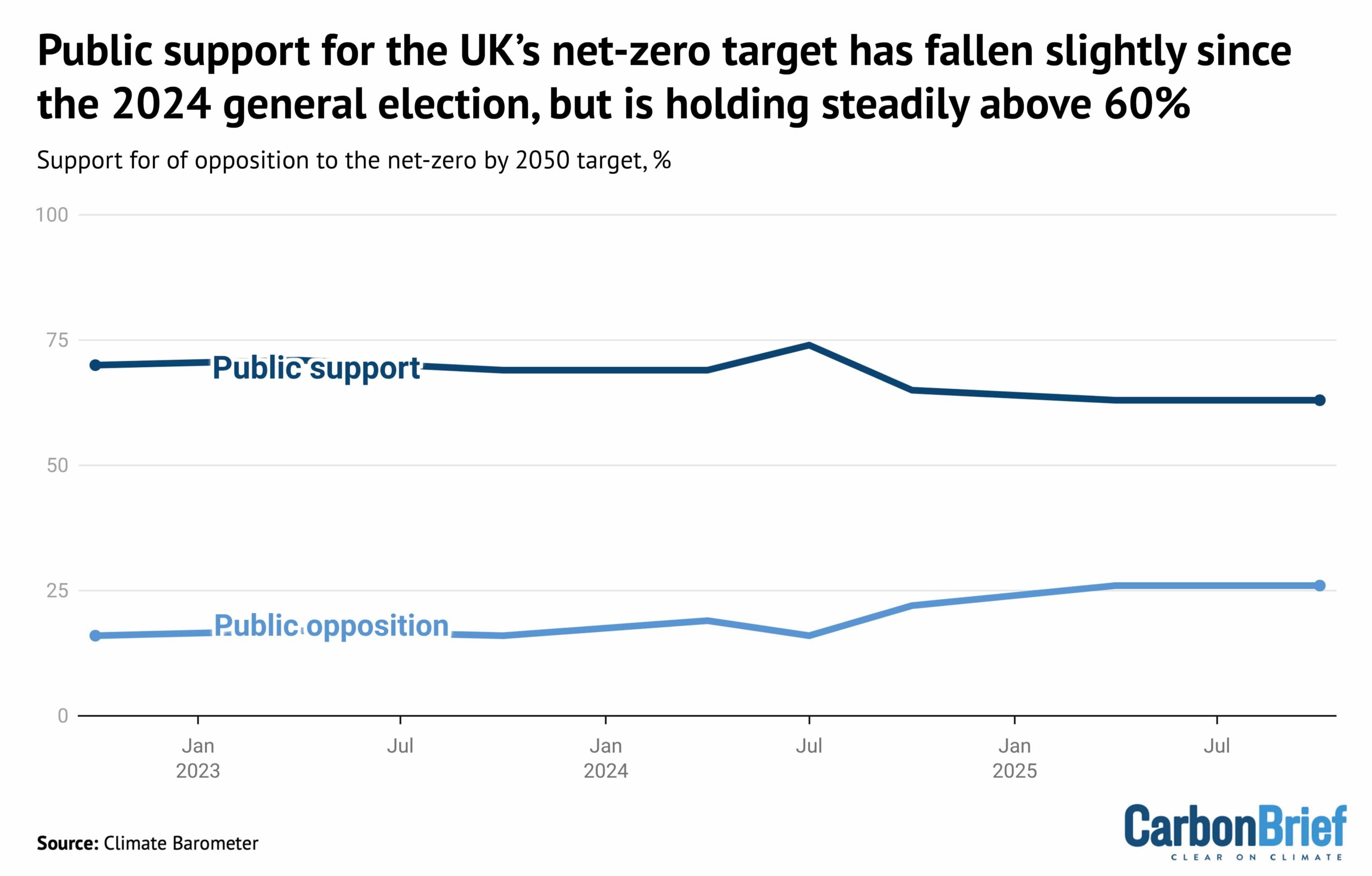

This week, after a historic Green Party byelection win, Carbon Brief looks at whether there really is a “greenlash” against climate policy in the UK.

Over the past year, the UK’s political consensus on climate change has been shattered.

Yet despite a sharp turn against climate action among right-wing politicians and right-leaning media outlets, UK public support for climate action remains strong.

Prof Federica Genovese, who studies climate politics at the University of Oxford, told Carbon Brief:

“The current ‘war’ on green policy is mostly driven by media and political elites, not by the public.”

Indeed, there is still a greater than two-to-one majority among the UK public in favour of the country’s legally binding target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, as shown below.

Steve Akehurst, director of public-opinion research initiative Persuasion UK, also noted the growing divide between the public and “elites”. He told Carbon Brief:

“The biggest movement is, without doubt, in media and elite opinion. There is a bit more polarisation and opposition [to climate action] among voters, but it’s typically no more than 20-25% and mostly confined within core Reform voters.”

Conservative gear shift

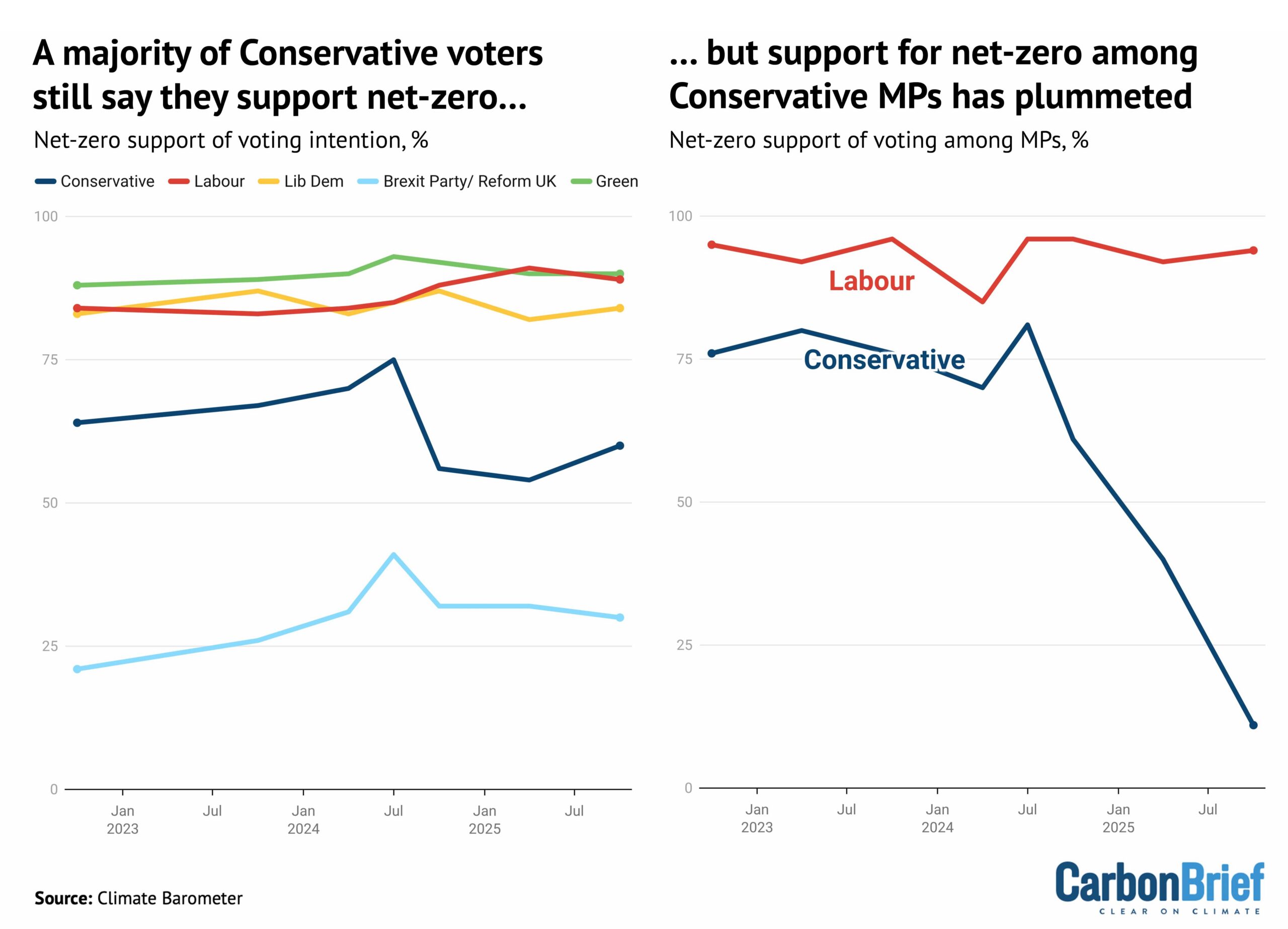

For decades, the UK had enjoyed strong, cross-party political support for climate action.

Lord Deben, the Conservative peer and former chair of the Climate Change Committee, told Carbon Brief that the UK’s landmark 2008 Climate Change Act had been born of this cross-party consensus, saying “all parties supported it”.

Since their landslide loss at the 2024 election, however, the Conservatives have turned against the UK’s target of net-zero emissions by 2050, which they legislated for in 2019.

Curiously, while opposition to net-zero has surged among Conservative MPs, there is majority support for the target among those that plan to vote for the party, as shown below.

Dr Adam Corner, advisor to the Climate Barometer initiative that tracks public opinion on climate change, told Carbon Brief that those who currently plan to vote Reform are the only segment who “tend to be more opposed to net-zero goals”. He said:

“Despite the rise in hostile media coverage and the collapse of the political consensus, we find that public support for the net-zero by 2050 target is plateauing – not plummeting.”

Reform, which rejects the scientific evidence on global warming and campaigns against net-zero, has been leading the polls for a year. (However, it was comfortably beaten by the Greens in yesterday’s Gorton and Denton byelection.)

Corner acknowledged that “some of the anti-net zero noise…[is] showing up in our data”, adding:

“We see rising concerns about the near-term costs of policies and an uptick in people [falsely] attributing high energy bills to climate initiatives.”

But Akehurst said that, rather than a big fall in public support, there had been a drop in the “salience” of climate action:

“So many other issues [are] competing for their attention.”

UK newspapers published more editorials opposing climate action than supporting it for the first time on record in 2025, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Global ‘greenlash’?

All of this sits against a challenging global backdrop, in which US president Donald Trump has been repeating climate-sceptic talking points and rolling back related policy.

At the same time, prominent figures have been calling for a change in climate strategy, sold variously as a “reset”, a “pivot”, as “realism”, or as “pragmatism”.

Genovese said that “far-right leaders have succeeded in the past 10 years in capturing net-zero as a poster child of things they are ‘fighting against’”.

She added that “much of this is fodder for conservative media and this whole ecosystem is essentially driving what we call the ‘greenlash’”.

Corner said the “disconnect” between elite views and the wider public “can create problems” – for example, “MPs consistently underestimate support for renewables”. He added:

“There is clearly a risk that the public starts to disengage too, if not enough positive voices are countering the negative ones.”

Watch, read, listen

TRUMP’S ‘PETROSTATE’: The US is becoming a “petrostate” that will be “sicker and poorer”, wrote Financial Times associate editor Rana Forohaar.

RHETORIC VS REALITY: Despite a “political mood [that] has darkened”, there is “more green stuff being installed than ever”, said New York Times columnist David Wallace-Wells.

CHINA’S ‘REVOLUTION’: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast reported from China on the “green energy revolution” taking place in the country.

Coming up

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean, Brasília

- 3 March: UK spring statement

- 4-11 March: China’s “two sessions”

- 5 March: Nepal elections

Pick of the jobs

- The Guardian, senior reporter, climate justice | Salary: $123,000-$135,000. Location: New York or Washington DC

- China-Global South Project, non-resident fellow, climate change | Salary: Up to $1,000 a month. Location: Remote

- University of East Anglia, PhD in mobilising community-based climate action through co-designed sports and wellbeing interventions | Salary: Stipend (unknown amount). Location: Norwich, UK

- TABLE and the University of São Paulo, Brazil, postdoctoral researcher in food system narratives | Salary: Unknown. Location: Pirassununga, Brazil

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding

The Lincolnshire constituency held by Richard Tice, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of the hard-right Reform party, has been pledged at least £55m in government funding for flood defences since 2024.

This investment in Boston and Skegness is the second-largest sum for a single constituency from a £1.4bn flood-defence fund for England, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

Flooding is becoming more likely and more extreme in the UK due to climate change.

Yet, for years, governments have failed to spend enough on flood defences to protect people, properties and infrastructure.

The £1.4bn fund is part of the current Labour government’s wider pledge to invest a “record” £7.9bn over a decade on protecting hundreds of thousands of homes and businesses from flooding.

As MP for one of England’s most flood-prone regions, Tice has called for more investment in flood defences, stating that “we cannot afford to ‘surrender the fens’ to the sea”.

He is also one of Reform’s most vocal opponents of climate action and what he calls “net stupid zero”. He denies the scientific consensus on climate change and has claimed, falsely and without evidence, that scientists are “lying”.

Flood defences

Last year, the government said it would invest £2.65bn on flood and coastal erosion risk management (FCERM) schemes in England between April 2024 and March 2026.

This money was intended to protect 66,500 properties from flooding. It is part of a decade-long Labour government plan to spend more than £7.9bn on flood defences.

There has been a consistent shortfall in maintaining England’s flood defences, with the Environment Agency expecting to protect fewer properties by 2027 than it had initially planned.

The Climate Change Committee (CCC) has attributed this to rising costs, backlogs from previous governments and a lack of capacity. It also points to the strain from “more frequent and severe” weather events, such as storms in recent years that have been amplified by climate change.

However, the CCC also said last year that, if the 2024-26 spending programme is delivered, it would be “slightly closer to the track” of the Environment Agency targets out to 2027.

The government has released constituency-level data on which schemes in England it plans to fund, covering £1.4bn of the 2024-26 investment. The other half of the FCERM spending covers additional measures, from repairing existing defences to advising local authorities.

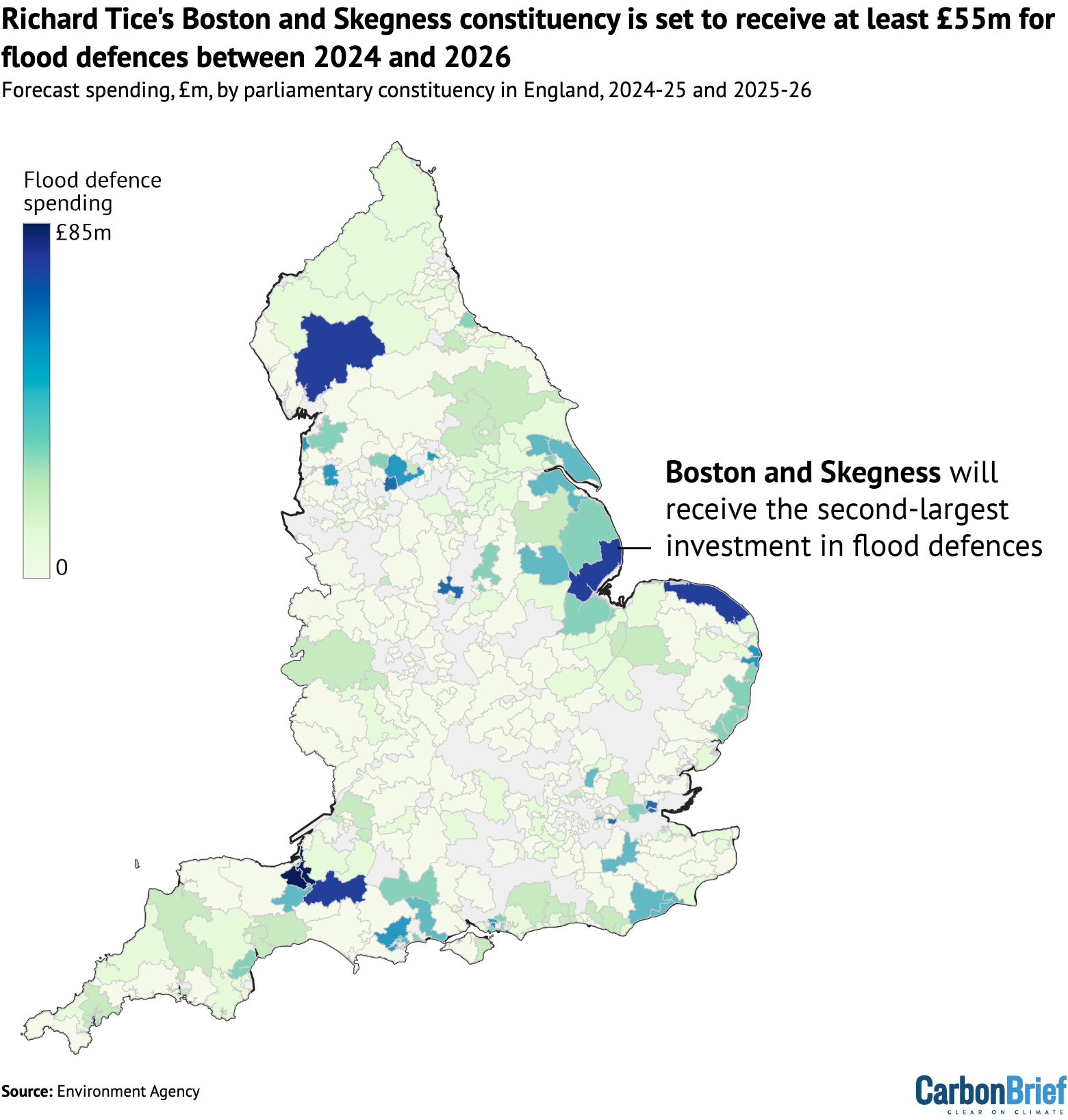

The map below shows the distribution of spending on FCERM schemes in England over the past two years, highlighting the constituency of Richard Tice.

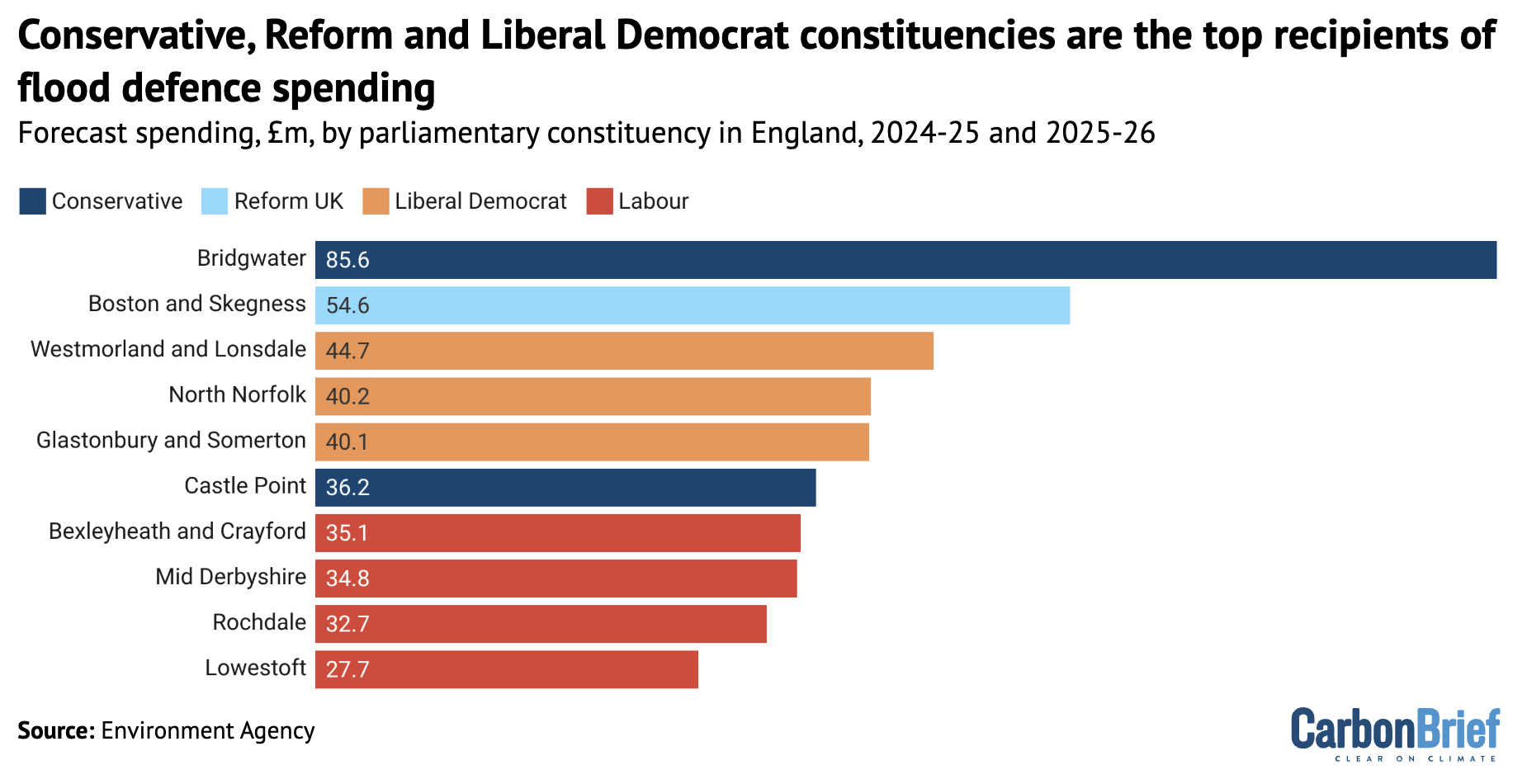

By far the largest sum of money – £85.6m in total – has been committed to a tidal barrier and various other defences in the Somerset constituency of Bridgwater, the seat of Conservative MP Ashley Fox.

Over the first months of 2026, the south-west region has faced significant flooding and Fox has called for more support from the government, citing “climate patterns shifting and rainfall intensifying”.

He has also backed his party’s position that “the 2050 net-zero target is impossible” and called for more fossil-fuel extraction in the North Sea.

Tice’s east-coast constituency of Boston and Skegness, which is highly vulnerable to flooding from both rivers and the sea, is set to receive £55m. Among the supported projects are beach defences from Saltfleet to Gibraltar Point and upgrades to pumping stations.

Overall, Boston and Skegness has the second-largest portion of flood-defence funding, as the chart below shows. Constituencies with Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs occupied the other top positions.

Overall, despite Labour MPs occupying 347 out of England’s 543 constituencies – nearly two-thirds of the total – more than half of the flood-defence funding was distributed to constituencies with non-Labour MPs. This reflects the flood risk in coastal and rural areas that are not traditional Labour strongholds.

Reform funding

While Reform has just eight MPs, representing 1% of the population, its constituencies have been assigned 4% of the flood-defence funding for England.

Nearly all of this money was for Tice’s constituency, although party leader Nigel Farage’s coastal Clacton seat in Kent received £2m.

Reform UK is committed to “scrapping net-zero” and its leadership has expressed firmly climate-sceptic views.

Much has been made of the disconnect between the party’s climate policies and the threat climate change poses to its voters. Various analyses have shown the flood risk in Reform-dominated areas, particularly Lincolnshire.

Tice has rejected climate science, advocated for fossil-fuel production and criticised Environment Agency flood-defence activities. Yet, he has also called for more investment in flood defences, stating that “we cannot afford to ‘surrender the fens’ to the sea”.

This may reflect Tice’s broader approach to climate change. In a 2024 interview with LBC, he said:

“Where you’ve got concerns about sea level defences and sea level rise, guess what? A bit of steel, a bit of cement, some aggregate…and you build some concrete sea level defences. That’s how you deal with rising sea levels.”

While climate adaptation is viewed as vital in a warming world, there are limits on how much societies can adapt and adaptation costs will continue to increase as emissions rise.

The post Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits