Governments are set to take a decisive step at Cop28 towards making a long-awaited global carbon market governed by the UN a reality.

The Paris Agreement establishes ways for countries to “voluntarily cooperate” to meet their climate targets by allowing emission reductions and removals to be traded.

In Dubai, negotiators will finalise the architecture of a new mechanism allowing countries to sell offsets to other governments, companies and individuals under Article 6.4.

It comes at a pivotal time. The voluntary carbon market has faced more intense scrutiny than ever this year with report after report casting doubt over its integrity. But for many, carbon credits remain a valuable tool to channel much-needed finance to developing countries.

The stakes are high for the new system to get it right and correct problems with existing systems. We outline four critical questions for the outcome from Dubai.

Which activities are eligible?

Deciding which activities can produce credits is an important and fraught question.

If the criteria are too restrictive, countries may struggle to obtain any meaningful financial support from the mechanism. Too broad and projects with questionable climate credentials, or other significant environmental and social concerns, will undermine their credibility.

Over the last year, the UN’s Article 6.4 supervisory body has been evaluating the eligibility of carbon removals: activities that take carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and store it. These can be nature-based, such as planting trees, or engineering-based, like machines to suck CO2.

Tensions emerged last May when an internal briefing note drafted by the UNFCCC secretariat advised against including technological solutions describing them as “unproven” and potentially risky.

While the supervisory body distanced itself from the document, it angered the industry which responded by flooding the consultation process with submissions putting their case forward.

It worked. The final recommendations, agreed upon after several extended meetings, do not directly encourage or discriminate against any type of activity.

Ministers still need to approve the package in Dubai. While a broad agreement is expected, certain groups may still have issues with it.

Papua New Guinea, representing the Coalition for Rainforest Nations, could be a blocker. It has long argued that credits issued for forest conservation under the Redd+ framework should automatically qualify for the new mechanism.

Most countries and experts disagree. “The intention of the Redd+ framework was never to generate credits”, says Pedro Martins Barata, a carbon markets expert at EDF and a former negotiator. “That mechanism is much less stringent. They should go through the same process of methodology submission and independent evaluation as all the other activities.”

Are the reductions additional and permanent?

As credits are used by governments or companies to compensate for their polluting activities, each unit must represent a real emission reduction. This has been a fundamental and long-standing issue with many carbon offsetting projects.

Among other things, rules need to make sure the activities would have not happened anyways without the carbon finance (additionality) and that any CO2 removed does not re-enter the atmosphere in a short amount of time (permanence).

The Supervisory Body has tackled those policy issues in the recommendations sent to Cop28 for approval.

On additionality, the document says that projects will have to take into account all relevant legislation and produce a detailed analysis of investment barriers to demonstrate that emission-cutting activities would have not occurred without the mechanism.

Experts told Climate Home these provisions should be stringent enough.

A community ranger standing in a mangrove forest restored as part of a nature protection project in Kenya. Photo: Anthony Ochieng / Climate Visuals Countdown

On permanence, concerns have been raised.

“The text leaves open the question of for how many years a credit is guaranteed to correspond to an actual removal without giving specific thresholds,” says Martins Barata, adding this should be established in further work.

Another contentious point is the possibility of relieving project developers of the duty to carry out permanence monitoring after they stop issuing credits. The risk is that, for example, protected trees could burn in a fire unleashing the stored carbon into the atmosphere.

The recommendations indicate this exemption can apply when a “negligible” risk of the emission removals being reversed is demonstrated.

Jonathan Crook of Carbon Market Watch argued the text could be tightened. “How do you define negligible risk? What sources will be accepted as evidence? These are all open questions that may cause potential issues,” he added.

What happens if a country wants to take back credits?

Article 6 has a provision to ensure that emission reduction activities are not counted twice, by both the seller and buyer, towards their respective climate plans. When a country transfers a credit to a government or a company it needs to deduct that from its greenhouse gas inventory.

As a result, countries need to strike a balance between attracting revenues and being able to meet their own climate plans.

But a contested rule could give struggling governments a way out. In Dubai, negotiators will be discussing whether countries may be allowed to withdraw any credits that have been previously authorised. This could also apply in cases where the projects are causing environmental and human rights violations.

Carbon Market Watch’s Crook said this provision poses a substantial threat. “If a country can revoke credits that have already been traded, and potentially used, then you have a serious risk of double counting,” he told Climate Home. “If revocations are allowed, at the very least they shouldn’t apply to credits already sold.”

Will the new market rescue the reputation of carbon credits?

A lot is riding on the Article 6.4 mechanism because of the impact it can have on the wider carbon offsetting world.

Crook said it needs to set a “high bar”, sending a strong message to the voluntary market that there needs to be improvements.

The new mechanism is set to include some positive elements that currently don’t exist in carbon markets used by corporations.

Already agreed rules have established that 2% of any credits traded in the new market will be automatically cancelled. This means that offsetting will not just be a zero-sum game, shifting emissions cuts from one place to another.

But when it comes to individual projects, experts said it was too early to say if they will have high integrity.

“You can have the best rules but it all comes down to implementation,” said Martins Barata. “They’re off to a good start. But come back to me when they start approving projects”.

If the recommendations are approved in Dubai, the new mechanism may start issuing credits towards the end of 2024.

Paradoxically, the first batch of credits to be traded may pose some of the biggest integrity risks. A process to transition credits created under the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM), the now-defunct UN carbon market established through the Kyoto Protocol, into the new mechanism is well underway.

CDM credits have been widely criticised for failing to contribute to real emissions reductions and causing human rights violations.

The post Four questions for Cop28 to settle about a global carbon market appeared first on Climate Home News.

https://www.climatechangenews.com/2023/11/29/four-questions-for-cop28-to-settle-about-a-global-carbon-market/

Climate Change

IPBES: Four key takeaways on how nature loss threatens the global economy

The “undervaluing” of nature by businesses is fuelling its decline and putting the global economy at risk, according to a major new report.

An assessment from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) outlines more than 100 actions for measuring and reducing impacts on nature across business, government, financial institutions and civil society.

A co-chair of the assessment says that nature loss is one of the most “serious threats” to businesses, but the “twisted reality is that it often seems more profitable to businesses to degrade biodiversity than to protect it”.

The “business and biodiversity” report says that global “finance flows” of more than $7tn (£5.1tn) had “direct negative impacts on nature” in 2023.

The new findings were put together by 79 experts from around the world over the course of three years, in what IPBES described as a “fast-track” assessment.

IPBES is an independent body that gives scientific advice to policymakers about biodiversity and ecosystems.

This is the “first report of its kind” to provide guidance on how businesses can contribute to 2030 nature goals, says IPBES executive secretary Dr Luthando Dziba in a statement.

Below, Carbon Brief explains four key findings from the “summary for policymakers” (SPM), which outlines the main messages of the report.

The full report is due to be released in the coming months after final edits are made.

- Businesses both depend on, and harm, nature

- Current practices ‘do not support’ efforts to halt and reverse biodiversity loss

- Businesses can act now to address their impacts on nature

- Government policies can drive a ‘just and sustainable future’ for nature and people

1. Businesses both depend on, and harm, nature

Businesses of all sizes rely on nature in one way or another, says the report.

The SPM outlines that biodiversity provides many of the goods and services businesses need, such as raw materials from the environment or controlled water flows to reduce flooding during wet seasons and provide water in dry seasons.

Biodiversity also “underpins genetic diversity” that informs the development of products in many industries, including pharmaceuticals and cosmetics.

Individual businesses often do not address their impacts and dependencies on nature, “in part due to their lack of awareness”, the SPM says.

They also often do not have the data or knowledge to “quantify their impacts on dependencies on biodiversity and much of the relevant scientific literature is not written for a business audience”, the report claims. It adds:

“Lack of transparency across value chains, including of the risks and opportunities related to the sustainability of resource extraction, use, reuse and waste management, is a further barrier to action.”

The report says it is well established that businesses depend on biodiversity, but also that the actions of businesses “continue to drive declines in biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people”.

It adds that the size of a business “does not always reflect the magnitude of its impacts”, with companies in sectors such as agriculture, forestry, fishing, electricity, energy and mining having “relatively high” direct impacts on nature.

A “failure” to account for nature as the economy has expanded over the past two centuries has “led to its degradation and unprecedented rates of biodiversity loss”, the SPM says. It adds:

“The decline in biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people has become a critical systemic risk threatening the economy, financial stability and human wellbeing with implications for human rights.”

It is well established that nature loss as a result of “unsustainable use” threatens the “ability of businesses, local economies and whole sectors to function”, the report details.

These risks and others – such as extreme weather events and critical changes to Earth systems – are “among the highest-ranked global risks over the next 10 years”, it adds.

The SPM notes further that it is well established that risks around climate change and biodiversity loss “may interact to amplify social and economic impacts”.

These risks have “disproportionate impacts on developing countries whose economies are more reliant on biodiversity and have more limited technical and financial capacity to absorb shocks”, the report adds.

2. Current practices ‘do not support’ efforts to halt and reverse biodiversity loss

The SPM says that it is well established that current political and economic practices “perpetuate business as usual and do not support the transformative change required to halt and reverse biodiversity loss”.

These practices have “commonly ignored or undervalued biodiversity, creating tension between business actions and the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity”, the report continues.

For example, the report says there is established but incomplete evidence that “time pressures on decision-making and timescales for investment returns and reporting by businesses – with an emphasis on quarterly earnings or annual reporting – are shorter than many ecological cycles”.

This prevents businesses from “adequately” considering nature loss in decision-making, says the SPM.

There is well established evidence that businesses fail to assign adequate value to “biodiversity and many of nature’s contributions to people, such as filtration of pollutants, climate regulation and pollination”, it continues.

As a result, “businesses bear little or no financial cost for negative impacts and may not generate revenue from positive impacts on biodiversity”, leading to “insufficient incentives for businesses to act to conserve, restore or sustainably use biodiversity”.

Prof Stephen Polasky, co-chair of the assessment and a professor of ecological and environmental economics at the University of Minnesota, said in a statement:

“The loss of biodiversity is among the most serious threats to business. Yet the twisted reality is that it often seems more profitable to businesses to degrade biodiversity than to protect it. Business as usual may once have seemed profitable in the short term, but impacts across multiple businesses can have cumulative effects, aggregating to global impacts, which can cross ecological tipping points.”

It is well established that policies from governments can “further accelerate biodiversity decline”, the SPM says.

It notes that, in 2023, global public and private financial spending with direct negative impacts on nature was estimated at $7.3tn.

This figure includes public subsidies that are harmful to nature (around $2.4tn) and private investment in high-impact sectors ($4.9tn), says the report.

Industries harmful to nature include fossil-fuel extraction, mining, deforestation and large-scale meat farming and fishing.

In contrast, just $220bn in public and private finance was directed to activities that contribute to protecting and sustainably using nature in 2023, adds the report.

(In recognition of the need to address public spending on activities that are destructive to nature, countries agreed to reduce biodiversity-harming subsidies by at least $500bn by 2030 as part of a global pact made in 2022.)

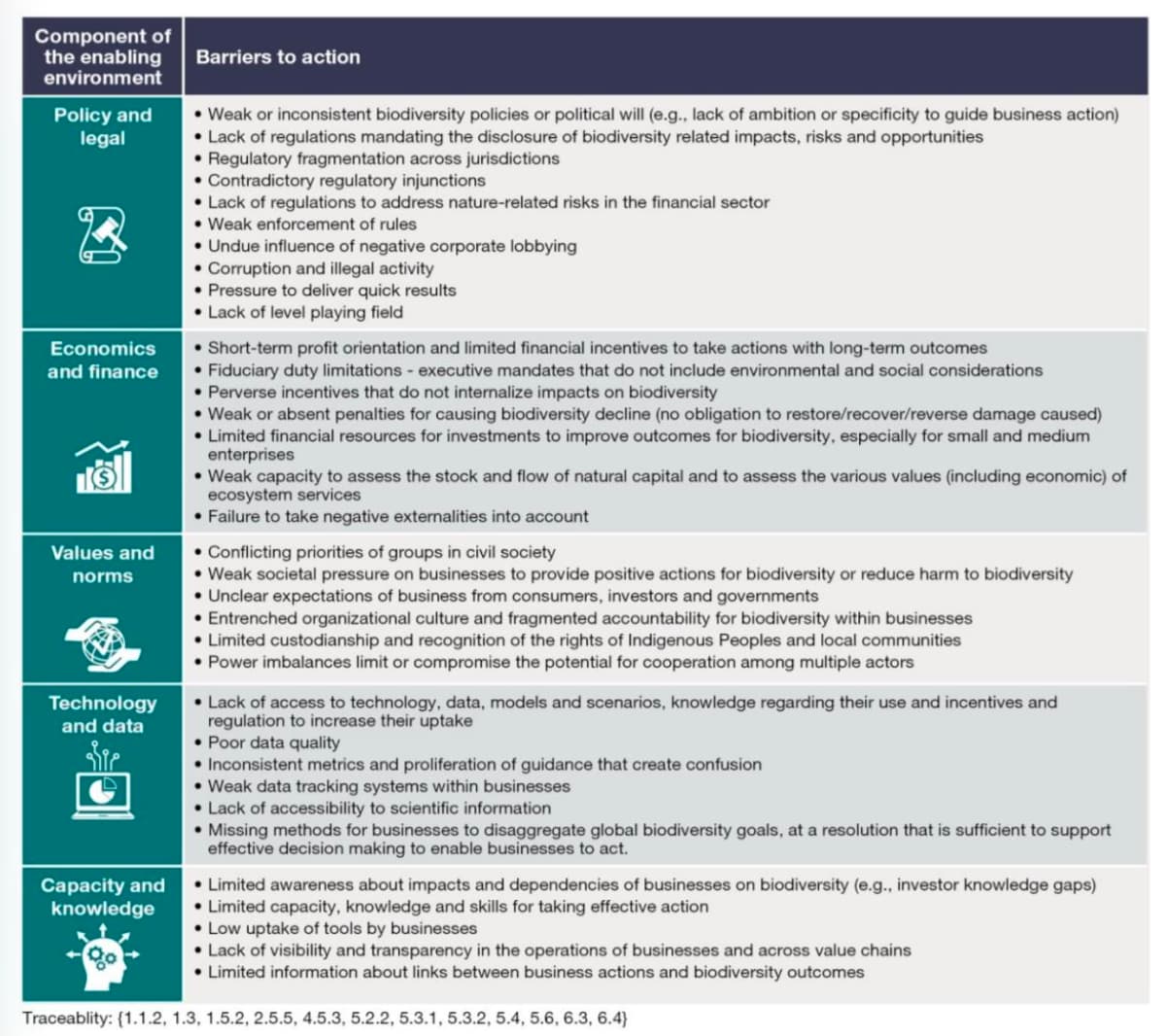

There are additional “barriers to action” facing businesses, ranging from challenging social norms to a lack of capacity, data or technology. These are summarised in the table below.

“These barriers do not affect all actors equally and may disproportionately affect small and medium-sized businesses and financial institutions in developing countries,” adds the report.

3. Businesses can act now to address their impacts on nature

The SPM says it is well established that the “transformative change” required to halt and reverse biodiversity loss requires action from “all businesses”.

However, the report continues that it is also well established that the current level of business action is “insufficient” to deliver this “transformative change”. This is, in part, because the “enabling environment is missing”, it says.

IPBES says all businesses have a responsibility to act, even if this responsibility is not shared “evenly”.

“Priority actions” that businesses should take differ depending on the size of the firm, the sector in which it operates in, as well as the company structure and its “relationship with biodiversity”, the report notes.

The exact actions businesses should pursue also depends on companies’ “degree of control and influence over stakeholders”, it says.

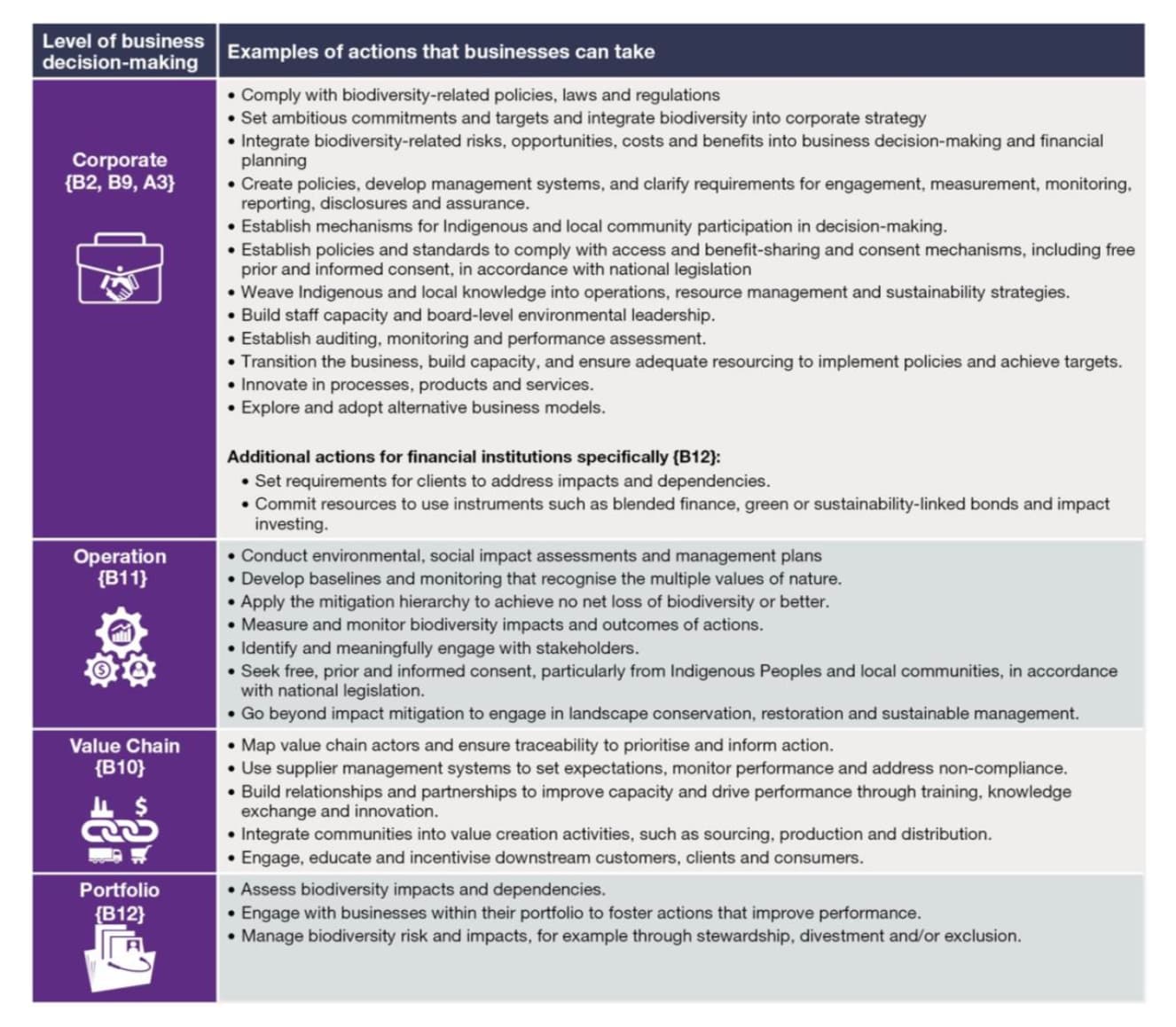

According to the report, firms can act across four “decision-making levels” – corporate, operations, value chain and portfolio – to measure and address impacts on biodiversity.

(“Corporate” refers to decisions focused on overarching strategy, governance and direction of the business; “operations” to day-to-day activities; “value chain” to the system and resources required to move a product or service from supplier to customer; and “portfolio” to investments and business assets).

The SPM sets out a series of examples for how businesses can act across all four levels. These are summarised in the table below.

At a corporate level, the report notes that firms can establish ambitious governance and frameworks that can then have a ripple effect across the other levels, according to the report. This includes the integration of biodiversity commitments and targets into corporate strategy.

The SPM says that corporate biodiversity targets are “most effective” when they are aligned with “national and global biodiversity objectives” and “take into consideration a business’s impacts and dependencies on biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people”.

At an operations level, businesses should focus on ensuring that their operations are located and managed in a way that benefits biodiversity, IPBES says. Environmental and social impact assessments and management plans that are supported by “credible monitoring of both actions and biodiversity outcomes” can underpin this effort, the SPM notes.

It says it is well established that using the “mitigation hierarchy” framework can help businesses deliver “lasting outcomes on the ground”. (The framework guides users towards limiting as far as possible the negative impacts on biodiversity from development projects by first avoiding, then minimising, restoring and offsetting impacts.)

Next, the report notes there are actions businesses can take to drive change within its broader spheres of influence, including suppliers, retailers, consumers and peers within industry. This is important, the SPM notes, as significant impacts and dependencies on biodiversity and nature “accrue” across the lifecycle of products or services, especially those that rely on raw materials.

The report notes there is established but incomplete evidence that efforts to “map” company value chains and improve traceability by linking products and materials to suppliers, locations and impacts can help “identify risks and prioritise actions”.

While noting that “mapping” beyond direct suppliers “often remains challenging” for businesses, the report adds:

“Examples at the corporate and value chain levels exist, such as companies in the chocolate industry that have made advances in recording biodiversity dependencies to improve business decisions through full traceability of materials and improved supplier control mechanisms.”

Elsewhere, the SPM notes that there is also established but incomplete evidence that consumer-focused measures – such as product labelling, education and incentives – can “shape behaviour and improve transparency”. However, it cautions that the effectiveness of these strategies is “constrained by consumer scepticism, certification costs and business models reliant on unsustainable consumption”.

The SPM also highlights that, at a “portfolio” level, financial institutions can shift finance away from harmful activities – for instance, companies whose products drive deforestation – and towards business activities with positive impacts for biodiversity and nature.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Matt Jones, co-chair of the report, explains the rationale behind including options for how businesses can address biodiversity impacts in the document:

“Businesses and governments in different countries are coming at this from a very different perspective. So we can’t present a set of really prescriptive ‘how tos’…but we can present a huge number of options for action that businesses, governments, financial institutions and civil society and other actors can all take.”

Elsewhere, the report says it is well established that “robust, transparent and credible reporting of actions and outcomes” is required to “inspire others”.

4. Government policies can drive a ‘just and sustainable future’ for nature and people

Both governments and financial institutions can set policies and create incentives to protect biodiversity and stem its decline, says the SPM.

According to the report, the types of policies that governments can put in place that have an influence over business include:

- Fiscal policies, such as subsidies and taxes.

- Land use or marine spatial planning and zoning, such as designating new national parks or areas protected for nature.

- Permitting for business activities that affect nature – for example, by requiring environmental impact assessments.

- Public procurement policy (rules for how governments purchase goods and services).

- Controls on advertising and the creation of standards to prevent “greenwashing”.

Governments can also promote action through paying for ecosystem services, creating environmental markets and through “multilateral benefit-sharing mechanisms”, which set out rules for ensuring profits from nature are shared equally, says the SPM.

It says this includes the Cali Fund, a fund that businesses can voluntarily pay into after reaping benefits from genetic resources found in biodiverse countries.

(The fund was agreed in 2024 with expectations that it could generate up to billions of dollars for conservation, but it has so far only attracted $1,000.)

Governments could also promote action by phasing out or reforming subsidies that are harmful for nature, as well as fostering positive incentives, according to the report.

Overall, governments can work with other actors to create an “enabling environment” to “incentivise actions that are beneficial for businesses, biodiversity and society for a just and sustainable future”, says the SPM. It adds:

“Creation of an enabling environment that provides incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people could align what is profitable with what is good for biodiversity and society.

“Creating this enabling environment would result in businesses and financial institutions being positive agents of change in transforming to a just and sustainable economic system, by addressing their impacts on biodiversity loss, climate change and pollution, which are all interconnected.”

The post IPBES: Four key takeaways on how nature loss threatens the global economy appeared first on Carbon Brief.

IPBES: Four key takeaways on how nature loss threatens the global economy

Climate Change

Vanuatu pushes new UN resolution demanding full climate compensation

Countries responsible for climate change could be required to pay “full and prompt reparation” for the damage they have caused, under a new United Nations resolution being pursued by the Pacific island state of Vanuatu, an initial draft shows.

The resolution seeks to turn into action last year’s landmark advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which found that states have a legal obligation to prevent climate harm and that breaches of this duty could expose them to compensation claims from affected countries.

Under the “zero draft” of the resolution seen by Climate Home News, the UN’s General Assembly, its main policy-making body, would also demand that countries stop any “wrongful acts” contributing to rising emissions, which may include the production and licensing of planet-heating fossil fuels.

Gas flaring soars in Niger Delta post-Shell, afflicting communities

‘Demand’ is the strongest verb calling for an obligation to comply in UN language, but it is rarely used in a resolution.

Countries would also be called upon to respect their legal obligations by enacting national climate plans consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5C and by adopting appropriate policies, including measures to “ensure a rapid, just and quantified phase-out of fossil fuel production and use”, the document shows.

End of March vote targeted

The draft, meant as a starting point for negotiations, was circulated last week by the government of Vanuatu following discussions with a dozen nations, including the Netherlands, Colombia and Kenya.

Countries are expected to take part in informal consultations between February 13-17 aimed at agreeing on wording that would secure broad support among UN member states, according to a statement from Vanuatu, which also led the diplomatic drive for the ICJ’s advisory opinion. A vote on the follow-up resolution could take place by the end of March, it added.

Ralph Regenvanu, Vanuatu’s climate minister, said respecting the court’s decision is “essential for the credibility of the international system and for effective collective action”.

“At a time when respect for international law is under pressure globally, this initiative affirms the central role of the International Court of Justice and the importance of multilateral cooperation,” he added in written comments.

New damage register and reparation mechanism

If adopted in its current form, the draft resolution would also create an “International Register of Damage”, which is described as a comprehensive and transparent record of evidence on loss and damage linked to climate change.

It would also ask the UN secretary-general to put forward proposals for a climate reparation mechanism that could coordinate and facilitate the resolution of compensation claims and promote financial models to help cover climate-related damage.

The fledgling Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD) – set up under the UN climate change regime – is set to hand out money to the first set of initiatives aimed at addressing climate-driven destruction later this year. However, the just-over $590 million currently in the fund’s coffers is dwarfed by the scale of need in developing countries, with loss and damage costs estimated to reach up to $400 billion a year by 2030.

Like other small island nations, Vanuatu is among the world’s most vulnerable countries to the effects of climate change, while having contributed the least to global warming. Last year’s ICJ decision stemmed from a March 2023 resolution led by the Pacific nation asking the world’s top court to define countries’ legal obligations in relation to climate change.

Regenvanu said in September 2025 that it was important to follow up the ICJ ruling with a new UNGA resolution because it could be approved by a majority vote, while progress can be blocked in other fora like the UN climate negotiations that require consensus for decisions.

The post Vanuatu pushes new UN resolution demanding full climate compensation appeared first on Climate Home News.

Vanuatu pushes new UN resolution demanding full climate compensation

Climate Change

China maximises battery recycling to shore up critical mineral supplies

Even the busiest streets of Shanghai have become noticeably quieter as sales of electric vehicles (EVs) skyrocketed in China, with charging points mushrooming in residential compounds, car parks and service stations across the megacity.

Many Chinese drivers have upgraded their conventional vehicles to electric ones – or already replaced old EVs with newer models – incentivised by the government’s generous trade-in policies, or tempted by the latest hi-tech features such as controls powered by artificial intelligence (AI).

“Different from conventional cars, EVs are more like fast-moving consumer goods, like smartphones,” explained Mo Ke, founder and chief analyst of Tianjin-based battery-research firm, RealLi Research. Their digital systems can become outdated quickly, so Chinese people typically change their EVs after five or six years while a conventional car can be driven much longer, he told Climate Home News.

EV sales surpassed 16 million in China last year. Roughly 10% of all vehicles on the road were electric, and half of all new vehicles sold carried a green EV number plate, with an average of 45,000 EVs rolling off the production lines each day.

But while fast-growing EV uptake is good news for Chinese EV and battery manufacturers, it is creating a huge volume of spent batteries.

Tsunami of spent batteries

Last year, China generated nearly 400,000 tonnes of old or damaged power batteries, largely consisting of vehicle batteries, according to government data. That is projected to rise to one million tonnes per year in 2030, officials forecast.

The growing waste problem has spurred the government to launch a series of new policies aimed at regulating the country’s battery recycling industry, which though well-established is marked by a high degree of informality – especially in the lucrative repurposing sector where discarded EV batteries are given a new lease of life in less energy-intensive uses, such as power storage.

China is determined to build a “standardised, safe and efficient” recycling system for batteries, Wang Peng, a director at China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, told a press conference as the government launched a recycling industry push in mid-January.

A policy paper published by the government last month detailed Beijing’s plans to mandate end-of-life recycling for EVs together with their batteries to prevent them from entering the grey, informal market, and establish a digital system to track the lifecycle of every battery manufactured in the country. Under the plans, EV and battery makers will be held responsible for recycling the batteries they produce and sell.

“The volume of the Chinese market is too big, so it has to take actions ahead of other countries,” Mo said, adding that he expected the government to release more details about implementation of the plans in the near future.

Critical minerals choke point

China’s strategy for the battery recycling sector could also prove a boon for the world’s largest battery producer by bolstering its supply of minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel and manganese.

Along with the looming large-scale battery retirement, policymakers’ focus on battery recycling also reflects concern about critical minerals supplies, said Li Yifei, assistant professor of environmental studies at New York University Shanghai. “The government also felt the increasing pressure of securing resources,” he told Climate Home News.

“When you set up an efficient battery-recycling system, you essentially secure a new source for critical minerals, and that can help you enhance economic security. That’s why the industry is so important,” Lin Xiao, chief executive of Botree Recycling Technologies, a Chinese company offering battery-recycling solutions, told Climate Home News.

Cobalt and nickel-free electric car batteries boom in “good news” for rainforests

China dominates global refining of several minerals critical for producing EV batteries, but it still relies on imports of the raw materials – a choke point Beijing is acutely aware of, industry experts say.

China imports more than 90% of its cobalt, nickel and manganese, which are important ingredients for EV batteries, Hu Song, a senior researcher with the state-run China Automotive Technology and Research Centre, told China’s CCTV state broadcaster in June 2025. For lithium, the figure was around 60% in 2024, according to a separate report.

“If [those] resources cannot be recycled, then we will keep facing strangleholds in the future,” Hu said.

Big players gain ground

Spent EV batteries can be reused in settings that have lower energy requirements, such as in two-wheelers or energy-storage systems. When they become too depleted for repurposing, they can be scrapped and shredded into “black mass”, a powdery mixture containing valuable metals that can be recovered.

Reflecting the size of China’s EV market, the country already dominates global battery recycling capacity. It is home to 78% of the world’s battery pre-treatment capacity, which is for scrapping and shredding, and 89% of the capacity for refining black mass, according to 2025 forecasts by Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, a UK firm tracking battery supply chains.

A number of large corporate players have emerged in the sector in recent years.

Huayou Cobalt, a major producer of battery minerals, has built a business model for recycling, repurposing and shredding old batteries, as well as refining black mass and making new batteries using recovered materials.

It recently signed a deal with Encory, a joint venture between BMW and Berlin-based environmental service provider Interzero, to develop cutting-edge battery-recycling technologies, with their first joint factory set to open in China this year.

Suzhou-based Botree Recycling Technologies has developed various solutions to turn retired power batteries into new ones. Meanwhile, Brunp Recycling, the recycling arm of Chinese battery giant CATL, has built large factories to recycle lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries, a type of lithium battery that does not use nickel or cobalt, as well as nickel manganese cobalt (NMC) batteries, which are more popular outside of China.

But Mo, of RealLi Research, said much remains to be done to regulate and formalise the battery recycling industry.

Underground workshops

Across China, small underground workshops plague the repurposing sector, rebundling depleted batteries for sale without following industry standards or complying with health and safety requirements.

Because these operators have lower operational costs, they are able to offer higher prices to EV owners to buy their old batteries, undercutting formal recycling companies.

“This creates distortions in the market where legitimate players, who invest in proper detection, hazardous waste treatment and compliance, struggle to compete purely on price,” a spokesperson at CATL, the world’s largest battery manufacturer, told Climate Home News.

Despite such challenges, CATL’s Brunp subsidiary produced 17,100 tonnes of lithium in 2024 from the 128,700 tonnes of depleted batteries it recycled that year, according to CATL’s annual report.

Recycling expertise in demand

Since it was founded in 2019, Botree has formed partnerships with several major clients, which together recycle about half of China’s power batteries, the company’s CEO Lin said.

As other countries grapple with rising volumes of spent batteries, Chinese recyclers are also finding new foreign markets for their know-how.

Botree has joined forces with Spanish consulting firm ILUNION and renewable energy company EFT-Systems to build a factory to recycle LFP batteries in Valladolid.

The plant, scheduled to start operation in 2027, will be able to recycle 6,000 tonnes of LFPs annually when it opens, accounting for roughly 15% of demand in the Spanish market.

“(The companies) tell us what batteries they recycle and what battery materials they want to regenerate,” Lin said. “We can design a complete process for them.”

The post China maximises battery recycling to shore up critical mineral supplies appeared first on Climate Home News.

China maximises battery recycling to shore up critical mineral supplies

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Renewable Energy2 years ago

GAF Energy Completes Construction of Second Manufacturing Facility