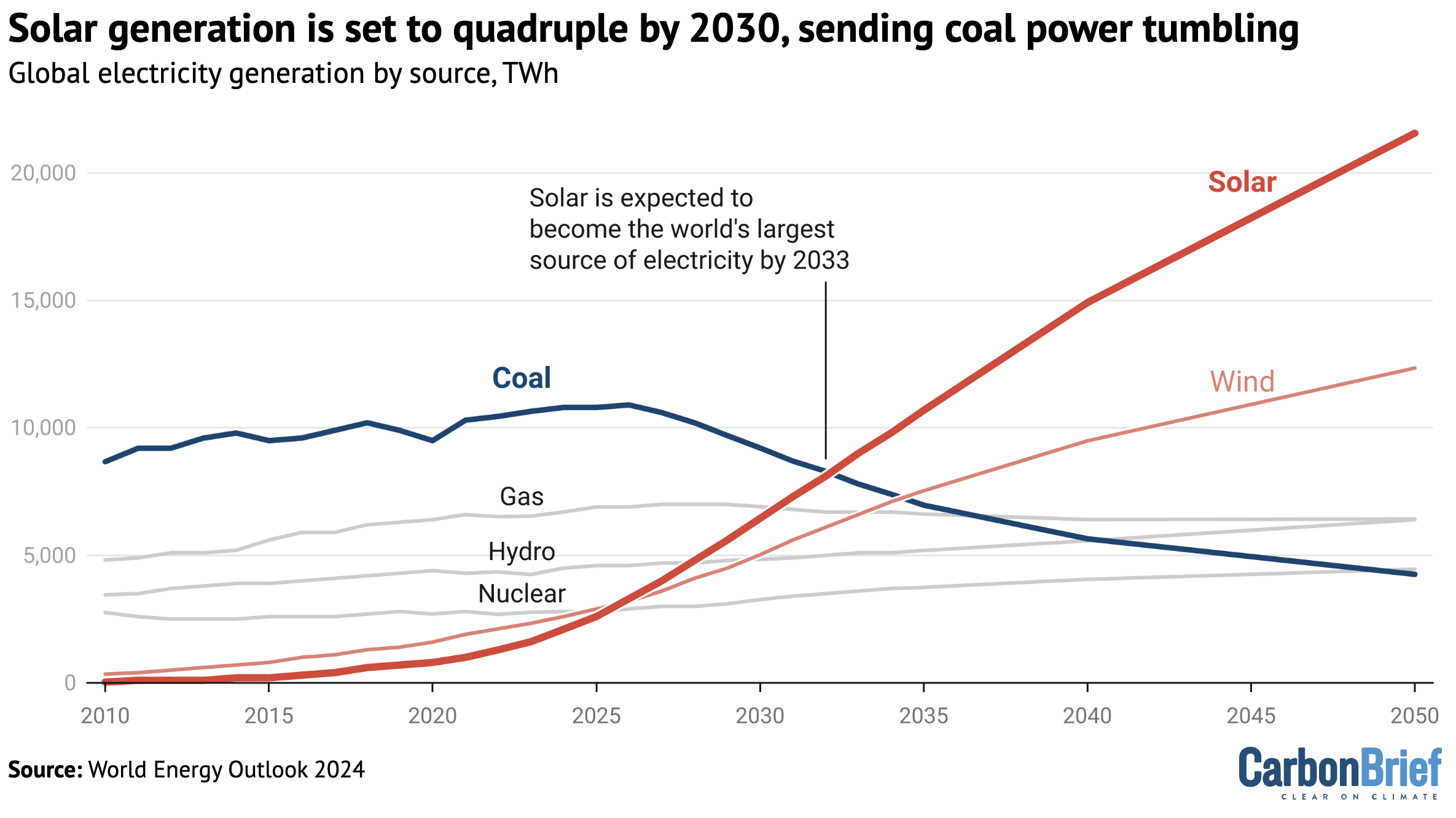

Global electricity generation from solar will quadruple by 2030 and help to push coal power into reverse, according to Carbon Brief analysis of data from the International Energy Agency (IEA).

The IEA’s latest World Energy Outlook 2024 shows solar overtaking nuclear, wind, hydro, gas and, finally, coal, to become the world’s single-largest source of electricity by 2033.

This solar surge will help kickstart the “age of electricity”, the agency says, where rapidly expanding clean electricity and “inherently” greater efficiency will push fossil fuels into decline.

As a result, the world’s energy-related carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions will reach a peak “imminently”, the IEA says, with its data indicating a turning point in 2025.

Other highlights from Carbon Brief’s in-depth examination of the IEA’s latest outlook include:

- Renewables will grow 2.7-fold by 2030, short of the “tripling” goal set at COP28.

- Still, clean energy is growing at an “unprecedented rate”, and will overtake coal, gas and then oil, to become the world’s largest source of energy “in the mid-2030s”.

- Low-carbon energy, including renewables and nuclear, will grow 44% by 2030, adding 48 exajoules (EJ) to global energy supplies.

- Global energy demand will only rise by 34EJ (5%) over the same period.

- This means clean energy will push each of the fossil fuels past their peak by 2030.

- Electric vehicles (EVs) are now expected to displace 6m barrels of oil per day (mb/d) by 2030, up from a figure of 4mb/d by 2030 in last year’s outlook.

Despite these changes, the world is on track to cut CO2 emissions to just 4% below 2023 levels by 2030, the agency warns, resulting in warming of 2.4C above pre-industrial temperatures.

It says there is an “increasingly narrow, but still achievable” path to staying below 1.5C, which would need more clean electricity, faster electrification and a 33% cut in emissions by 2030.

This year, in light of heightened geopolitical risks and uncertainties, the IEA explores “sensitivities” around its core outlook. These include slower (or faster) uptake of electric vehicles (EVs), as well as faster growth in data-centre loads and more heatwave-driven demand for air conditioning.

The agency maintains that, even when these sensitivities are combined, global demand for coal, oil and gas – as well as CO2 emissions – would peak no more than a few years later than expected.

(See Carbon Brief’s coverage of previous IEA world energy outlooks from 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016 and 2015.)

World energy outlook

The IEA’s annual World Energy Outlook (WEO) is published every autumn. It is widely regarded as one of the most influential annual contributions to the understanding of climate and energy trends.

The outlook explores a range of scenarios, representing different possible futures for the global energy system. These are developed using the IEA’s “Global Energy and Climate Model”.

The 1.5C-compatible “net-zero emissions by 2050” (NZE) scenario was introduced in 2021 and updated in September 2023. The NZE is revised again in the WEO 2024 to reflect the fact that global CO2 emissions reached another record high last year, rather than falling.

The report says that the path to 1.5C is “increasingly narrow, but still achievable”. However, it adds:

“Every year in which global emissions rise and actions fall short of what is needed for the future makes this pathway steeper and harder to climb.”

Alongside the NZE is the “announced pledges scenario” (APS), in which governments are given the benefit of the doubt and assumed to meet all of their climate goals on time and in full.

Finally, the “stated policies scenario” (STEPS) represents “the prevailing direction of travel for the energy system, based on a detailed assessment of current policy settings”. Here, the IEA looks not at what governments are saying, but what they are actually doing.

Annex B of the report breaks down the policies and targets included in each scenario. In effect, the IEA is judging the seriousness of each target and whether it will be followed through.

For example, the provisions of the European Green Deal are included in the STEPS. But the EU target to cut emissions to 55% below 1990 levels by 2030 is only met under the APS.

Since last year’s report, some 38 countries responsible for a third of global energy-related CO2 emissions have introduced new clean-energy measures, the IEA says.

It mentions South Korea’s 11th electricity plan, which “includes a significant expansion of nuclear, wind and solar”, and the new UK government “lift[ing] the de-facto ban on new onshore wind”.

(It says there have also been “some rollbacks” of climate policy over the past year, such as Javier Milei’s reforms in Argentina, but the global impact of these is “relatively small”.)

The report emphasises that “none of the scenarios should be viewed as a forecast”. It adds:

“Our scenario analysis is designed to inform decisionmakers as they consider options, not to predict how they will act.”

Earlier this year, some US politicians and analysts criticised the IEA’s work, in particular, its suggestion in WEO 2023 that demand for oil, coal and gas would each peak before 2030. They also argued that the IEA was straying from its core focus on energy security.

At the time, the agency defended its approach in a response to Senate Republicans.

This year’s edition goes on to reiterate the IEA’s view that fossil fuels will peak this decade – and pushes back on the idea that climate change and clean energy are outside its mission.

It says that “more efficient, cleaner energy systems can reduce energy security risks” and that a “comprehensive approach to energy security…needs to extend beyond traditional fuels”.

In his foreword to the report, IEA executive director Fatih Birol adds:

“The concept of energy security goes well beyond safeguarding against traditional risks to oil and natural gas supplies, as important as that remains for the global economy.”

He says that, in addition to those issues, energy security includes access to affordable energy supplies, secure supply chains for clean-energy technologies and dealing with the rising threat of extreme weather disruption to energy systems. Birol’s foreword continues:

“The analysis in this year’s outlook reinforces my long-held conviction that energy security and climate action go hand-in-hand…This is because deploying cost-competitive clean energy technologies represents a lasting solution not only for bringing down emissions, but also for reducing reliance on fuels that have been prone to volatility and disruption.”

Discussing the controversy over fossil-fuel peaking in a press briefing to launch this year’s report, Birol said that the latest data – and the outlooks of several major international oil and gas companies – had “confirmed and reconfirmed” the IEA’s position on oil demand.

Birol said press reports had described the latest data as “vindication” for the IEA’s forecast of minimal growth in oil demand this year. But he added: “It’s not a vindication of the IEA, it’s a vindication of numbers and objective analysis.”

Nevertheless, this year’s outlook puts extra emphasis on the uncertainty surrounding its scenarios. It devotes an entire chapter to exploring “sensitivities”, such as slower growth in EV sales or a more rapid escalation of heatwaves driving demand for air conditioning.

Even when these sensitivities are combined in ways that would slow climate action, however, the IEA says that oil demand still peaks and begins to decline by 2035. Similarly, global CO2 emissions would be less than 2% higher in 2030 and 1% in 2035 than in the core outlook.

‘Age of electricity’

A central theme of this year’s outlook is the idea that the global energy system is entering a new era, defined by rapid growth in electricity demand and a surge in clean electricity supplies.

In a press release accompanying the report, Birol calls this new era the “age of electricity”, in contrast to the earlier “age of coal” and “age of oil”. (The “golden age of gas”, predicted by the IEA in 2012, was prematurely brought to an end by the global energy crisis, driven by high gas prices.)

Birol says “the future of the energy system is electric” and that it is “moving at speed” towards “increasingly be[ing] based on clean sources of electricity”. In the report foreword he adds:

“The latest outlook also confirms that the contours of a new, more electrified energy system are becoming increasingly evident, with major implications on how we meet rising demand for energy services. Clean electricity is the future, and one of the striking findings of this outlook is how fast demand for electricity is set to rise, with the equivalent of the electricity use of the world’s ten largest cities being added to global demand each year.”

The IEA says that electricity demand is set to rise six times faster than global energy demand overall, in the years out to 2035, having only been twice as fast since 2010.

Moreover, despite a rapid acceleration in recent years, clean electricity has not yet grown fast enough to meet rising demand, leaving space for fossil-fueled power to continue expanding.

Global solar capacity is now 40-times larger than it was in 2010 and wind six times larger, the outlook notes, and a record 560 gigawatts (GW) of renewables were added in 2023.

Yet growth in clean electricity supplies has still fallen short of rising demand, meaning coal power has climbed 23% since 2010 and gas by 36%, raising emissions in the sector by 20%.

This is now set to change. The report says:

“It is now cheaper to build onshore wind and solar power projects than new fossil-fuel plants almost everywhere around the world, and the economic arguments remain strong even when considering the accompanying investment required to cope with their variability of generation.”

Renewables are only on track to expand 2.7-fold from 2022 to 2030 – short of the tripling target set at COP28 – but clean electricity will still outstrip rising demand, out to 2030 and beyond.

The IEA data shows that the amount of electricity generated from solar power alone is set to quadruple from 2023 levels by 2030 – and to climb more than nine-fold by 2050.

This means that solar will overtake nuclear, hydro and wind in 2026, gas in 2031 – and then coal by 2033 – to become the world’s largest source of electricity, as shown in the figure below.

Along with a doubling of wind generation and more modest gains for nuclear and hydro by 2030, clean electricity will push coal power into reverse, declining 13% by 2030 and 34% by 2035.

(The outlook sees modest growth of 6% by 2030 for gas power, but most of this would be erased by 2035 as clean electricity supplies continue to expand.)

The IEA says that China was responsible for 60% of worldwide renewable installations last year – and will add 60% of new capacity out to 2030. This means that by the early 2030s, solar generation in China alone is set to exceed the US’ current total electricity demand.

Notably, this year’s report includes another significant boost to the outlook for solar under current policy settings.

The IEA now sees global solar capacity exceeding 16,000GW by 2050, some 30% higher than expected last year and nearly 11-times higher than it thought in 2015, as shown in the figure below.

By 2023, the world had already installed 1,610GW of solar capacity. This comfortably exceeded the 1,405GW of capacity that the IEA had expected in 2050, under prevailing policy settings in its 2015 world energy outlook, released before the Paris Agreement later that year.

Similarly, this year’s outlook says battery storage capacity will reach 1,630GW by 2030. Only two years ago, it had said battery capacity would reach just 1,296GW by 2050.

In addition to raising the outlook for solar and storage, however, this year’s report also includes significantly higher global electricity demand, which has been revised upwards by 5% in 2030.

This 1,700 terawatt-hour (TWh) revision to global demand in 2030 – nearly equivalent to current electricity use in India – is much larger than the 1,000TWh adjustment for solar.

As a result, the IEA has also raised its outlook for coal power in 2030 by nearly 900TWh.

The IEA says that higher electricity demand is “mainly” down to “increased light industry activity, notably in China, much of it associated with a rapid rise in clean-technology manufacturing”.

Other factors include faster-than-expected adoption of EVs, more rapid electrification in industry in developing countries and the rise of data centres.

(The IEA, nevertheless, pours cold water on over-hyped reporting of AI-driven growth in data-centre electricity demand, which it sees accounting for barely 3% of growth to 2030, overall.)

Alongside growth in wind and solar, the report stresses the need for “a wide set of dispatchable low-emissions sources, including hydropower, bioenergy and nuclear power”.

It also emphasises the need for rising investment in electricity grids and storage. Spending in these areas is currently only two-thirds of investment in renewables, whereas parity will be needed to facilitate clean electricity expansion and ensure resilience to extreme weather and cyberattacks.

Fossil fuels peak by 2030

The “age of electricity” will have important implications for the current fossil-fuelled energy system, the report says. These include a reduction in the rate of global energy demand growth, even as demand for “energy services” – such as heat and mobility – rises rapidly in the developing world.

Explaining this apparent paradox, the IEA says that much of the energy released by burning fossil fuels is lost as waste heat. In contrast, a “more electrified, renewables-rich system is inherently more efficient”. This means less energy will be required to deliver the same energy services.

For example, electric technologies such as EVs and heat pumps deliver mobility and heat much more efficiently than internal combustion engines or fossil fuel boilers, the report says.

As the “age of electricity” gains pace, sources of energy demand across all sectors of the economy will be increasingly electrified, including heating, cooling, mobility and industrial processes.

This means the share of final energy consumption met by electricity will rise from 17% in 2010 and 20% in 2023 to 24% by 2030 and 32% by 2050, the outlook says – a more than 50% rise on current levels of electrification.

(Earlier this year, the Rocky Mountain Institute said China had “leapfrogged” other major countries in terms of rapid electrification, becoming what it termed the “first major electrostate”. Electricity already accounts for 26% of its energy consumption and will reach nearly 45% by 2050.)

Notably, the IEA has also been edging up its outlook for electrification, reflecting repeated boosts to its view on the deployment of electric technologies such as EVs and heat pumps. In 2015, it only expected electricity to meet 26% of final demand in 2050.

The rise of electrification, fed by expanding clean electricity sources, is now on the cusp of sending fossil fuels into decline, the outlook shows. As noted above, this year’s report reiterates the agency’s view that coal, oil and gas will each reach a peak this decade. It says:

“In the STEPS, coal demand begins to decline around 2025, while oil and natural gas demand both peak towards the end of the decade.”

Indeed, the outlook data shows global energy supply growing 34EJ (5%) by 2030, with this growth easily outpaced by clean-energy expansion of 48EJ (44%). As a result, fossil fuels in aggregate will be pushed into decline, as shown in the figure below.

The chart above shows how shifts in the global policy and technology landscape since the 2015 Paris Agreement have transformed the outlook for fossil-fuel growth.

Instead of the continuation of historical growth rates expected before Paris, the IEA has in recent years shifted its outlook, to a peak and increasingly steep decline in fossil-fuel demand.

Indeed, this year’s report points to fossil-fuel demand under current policy settings declining at a rate that is nearly in line with the climate pledges countries had made in 2021.

For example, the report says that China’s rapid uptake of EVs is spurring a “major slowdown” in oil demand growth globally, which is “wrong-footing oil producers”. It explains:

“China has been the engine of oil-market growth in recent decades, but that engine is now switching over to electricity.”

Indeed, the rise of electric mobility around the world is set to displace 6mb/d of oil demand by 2030, the outlook says, up from the 4mb/d it expected last year.

It notes that despite negative reporting, global EV sales were up 25% in the first half of 2024, with China accounting for 80% of the increase, but the rest of the world’s market also up 10%.

Nevertheless, the chart above illustrates the large gap between the current trajectory of the global energy system and what would be needed to meet existing national climate pledges, let alone the Paris Agreement target of limiting warming to “well-below” 2C or 1.5C.

Insufficient progress on emissions

This year’s outlook puts the gap between climate ambition and the world’s current trajectory into stark relief, saying that prevailing policy settings would likely see warming reach 2.4C this century.

Reflecting the marginally higher outlook for coal use in the short term, but more rapid fossil fuel declines in the medium and longer terms, this 2.4C assessment is the same as last year’s report.

This combination of changes is illustrated in the figure below, showing how the outlook for global energy-related CO2 emissions (grey line) has changed since 2015 (dashes). The IEA now says CO2 emissions will peak “imminently”, with its data pointing towards a peak in 2025.

(Last year, the outlook said emissions would peak by 2025 at the latest.)

The chart above illustrates how new policies and technological progress since the Paris Agreement are bending the curve of global CO2 emissions away from the 3.5C of warming expected in 2015.

Still, it also shows the massive gap that would need to be bridged in order to meet national climate pledges for 2030 and for reaching net-zero emissions by mid-century (blue line). And it shows the huge scale of the gap to the “increasingly narrow, but still achievable” path to 1.5C.

While current policy settings would cut global CO2 emissions to 4% below 2023 levels by 2030, according to the IEA, a far larger 33% reduction would be needed for 1.5C.

A separate report from the IEA, published last month, shows how countries could close most of this gap “by fully implementing the 2030 goals they agreed at COP28”.

These goals included doubling the rate of energy efficiency improvements and tripling global renewable capacity by 2030. Together, these two elements “could provide larger emissions reductions by 2030 than anything else”, the outlook says.

It reinforces the key changes that would be needed to get on track for current climate pledges – which would limit warming in 2100 to around 1.7C – or to limit warming to 1.5C.

In broad terms, this would mean even faster electrification and deployment of clean-energy technologies, as well as taking rapid action to cut methane emissions from the oil and gas industry.

(Instead of electricity’s share of final energy use increasing from 20% to 32% by 2050, as under current policy settings, electrification rates would double to 42% by 2050, if climate pledges are met, and would nearly triple to 55%, if the world gets on track for 1.5C.)

More specifically, the IEA points to “seven key clean-energy technologies”: solar; wind; nuclear; EVs; heat pumps; low-emissions hydrogen; and carbon capture and storage.

The report says the world has “the need and the capacity to go much faster” in these areas, which – unlike the current trajectory – would bring global emissions into a “meaningful decline”.

Spotlighting the need for a positive outcome in upcoming climate-finance discussions at the COP29 UN summit in November in Baku, Azerbaijan, the IEA says that high financing costs and project risks are limiting the spread of these clean-energy technologies in developing countries.

Concluding his report foreword, the IEA’s Birol emphasises the choices facing governments, investors and consumers. He writes:

“This WEO highlights, once again, the choices that can move the energy system in a safer and more sustainable direction. I urge decision makers around the world to use this analysis to understand how the energy landscape is changing, and how to accelerate this clean energy transformation in ways that benefit people’s lives and future prosperity.”

The outlook warns that decisionmakers “too often entrench the flaws in today’s energy system, rather than pushing it towards a cleaner and safer path”. It adds: “[L]ocking in fossil fuel use has consequences…the costs of climate inaction…grow higher by the day.”

The post Analysis: Solar surge will send coal power tumbling by 2030, IEA data reveals appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Solar surge will send coal power tumbling by 2030, IEA data reveals

Climate Change

The Farming Industry Has Embraced ‘Precision Agriculture’ and AI, but Critics Question Its Environmental Benefits

Why have tech heavyweights, including Google and Microsoft, become so deeply integrated in agriculture? And who benefits from their involvement?

Picture an American farm in your mind.

Climate Change

With Love: Living consciously in nature

I fell flat on my backside one afternoon this January and, weirdly, it made me think of you. Okay, I know that takes a bit of unpacking—so let me go back and start at the beginning.

For the last six years, our family has joined with half a dozen others to spend a week or so up at Wangat Lodge, located on a 50-acre subtropical rainforest property around three hours north of Sydney. The accommodation is pretty basic, with no wifi coverage—so time in Wangat really revolves around the bush. You live by the rhythm of the sun and the rain, with the days punctuated by swimming in the river and walking through the forest.

An intrinsic part of Wangat is Dan, the owner and custodian of the place, and the guide on our walks. He talks about time, place, and care with great enthusiasm, but always tenderly and never with sanctimony. “There is no such thing as ‘the same walk’”, is one of Dan’s refrains, because the way he sees it “every day, there is change in the world around you” of plants, animals, water and weather. Dan speaks of Wangat with such evident love, but not covetousness; it is a lightness which includes gentle consciousness that his own obligations arise only because of the historic dispossession of others. He inspires because of how he is.

One of the highlights this year was a river walk with Dan, during which we paddled or waded through most of the route, with only occasional scrambles up the bank. Sometimes the only sensible option is to swim. Among the life around us, we notice large numbers of tadpoles in the water, which is clean enough to drink. Our own tadpoles, the kids in the group, delight in the expedition. I overhear one of the youngest children declaring that she’s having ‘one of the best days ever’. Dan looks content. Part of his mission is to reintroduce children to nature, so that the soles of their feet may learn from the uneven ground, and their muscles from the cool of the water.

These moments are for thankfulness in the life that lives.

It is at the very end of the walk when I overbalance and fall on my arse—and am reminded of the eternal truth that rocks are hard. As I gingerly get up, my youngest daughter looks at me, caught between amusement and concern, and asks me if I’m okay.

I have to think before answering, because yes, physically I’m fine. But I feel too, an underlying sense of discomfort; it is that omnipresent pressure of existential awareness about the scale of suffering and ecological damage now at large in the world, made so much more immediately acute after Bondi; the dissonance that such horrors can somehow exist simultaneously with this small group being alive and happy in this place, on this earth-kissed afternoon.

How is it okay, to be “okay”? What is it to live with conscience in Wangat? Those of us who still have access to time, space, safety and high levels of volition on this planet carry this duality all the time, as our gift and obligation. It is not an easy thing to make sense of; but for me, it speaks to the question of ‘why Greenpeace’? Because the moral and strategic mission-focus of campaigning provides a principled basis for how each of us can bridge that interminable gulf.

The essence of campaigning is to make the world’s state of crisis legible and actionable, by isolating systemic threats to which we can rise and respond credibly, with resources allocated to activity in accordance with strategy. To be part of Greenpeace, whether as an activist, volunteer supporter or staff member, is to find a home for your worries for the world in confidence and faith that together we have the power to do something about it. Together we meet the confusion of the moment with the light of shared purpose and the confidence of direction.

So, it was as I was getting back up again from my tumble and considering my daughter’s question that I thought of you—with gratitude, and with love–-because we cross this bridge all the time, together, everyday; to face the present and the future.

‘Yes, my love’, I say to my daughter, smiling as I get to my feet, “I’m okay”. And I close my eyes and think of a world in which the fires are out, and everywhere, all tadpoles have the conditions of flourishing to be able to grow peacefully into frogs.

Thank you for being a part of Greenpeace.

With love,

David

Climate Change

Without Weighing Costs to Public Health, EPA Rolls Back Air Pollution Standards for Coal Plants

The federal Mercury and Air Toxics Standards for coal and oil-fired power plants were strengthened during the Biden administration.

Last week, when the Environmental Protection Agency finalized its repeal of tightened 2024 air pollution standards for power plants, the agency claimed the rollback would save $670 million.

Without Weighing Costs to Public Health, EPA Rolls Back Air Pollution Standards for Coal Plants

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits