I’ve been thinking a lot about futurism these past few weeks. And wondering what it is that makes dreaming without bounds so dang difficult. I participated in a strategic planning session for an org that I love recently. We were invited to imagine the organization 20 years in the future and folks struggled to actually think beyond the current ecosystems. I recalled another brainstorming session I found myself in a few years ago where the facilitator asked us to dream our greatest wishes for the neighborhood. My colleague and I drew an image of beloved community with collectively owned businesses, cooperative child care, and locally grown food. The state government representative at the table’s deepest desire for the neighborhood was an additional 100 section 8 vouchers. Why is it so hard for us to creatively imagine the future in expansive ways?

I care about this because I know that we need to creatively and collectively imagine, in detail, the world we want to see post climate crisis in order to build the path to that future. As Ayana Elizabeth Johnson, author of What If We Get It Right?, reminds us, “Addressing the climate crisis requires… a rethinking of the fundamental systems that we rely on.”

We live in a state of collective shock these days, full of grief and anger as we navigate from one unimaginable or unthinkable current event to the next. I know I am often just thinking about how to survive the day and the week. No wonder it is a challenge to imagine the future with optimism and creativity. I began to wonder what might be the scaffolding of conversation and thinking prompts that could open up our minds to possibility, to dreaming.

Futurist and game designer Jane McGonigal talks about mental time travel as a useful experiment and practice. She starts by asking us to imagine walking up tomorrow morning in vivid detail: where will you be, what will you be wearing, what will the temperature and the light be like, how will you be awakened, how will you feel physically and emotionally, what will be the first thing you do? Then imagine yourself walking up on a morning 10 years from tomorrow. Fill in all the same vivid details like you did before.

In the future scenarios we have to choose the details, choose what to imagine. And as we project ourselves into that future, we carry with us our hopes, our values, and all that we care about. This scenario building is exactly what we must do to build a just and abundant world beyond the climate crisis. As we build out the details of the world we want, we get to ask ourselves, ‘Is this the world I want to wake up in?’, ‘What do I need to be ready for this world?’, and ‘Should I try to change what I am doing today to make this future more or less likely?’.

We can only build what we can imagine. We can decide how the future will be different.

McGonigal invites us to engage in social mental time travel, to do this together, with the challenge to open our calendars and scroll 10 years ahead to the future. Put something in that calendar in 2035 — an event, a celebration, something. Then invite 4 or 5 others to that event, begin imagining together what that future day might hold. Invite me, I would love to be part of imagining the future with you.

Friends, life out here for climate justice non-profits is hard. Unlike during the first time the chief climate change denier was in office, support for our important work is shrinking. We are in the midst of an End of Fiscal Year fundraising campaign. Your gift enables us to continue inspiring educators and young people to dream about the future and co-create the solutions that bring us there. Thanks.

Susan Phillips

Executive Director

Illustration: João Queiroz

The post To Build a Beautiful World, You First Have to Imagine It appeared first on Climate Generation.

Climate Change

Environmental Groups Challenge Air Permit for Natural Gas Expansion at Atlanta Plant

The Sierra Club and Southern Environmental Law Center are suing over state regulators’ approval of new gas turbines at Plant Bowen, citing concerns about worsening air quality.

Atlanta has spent decades battling smog and air pollution. Now, state regulators have cleared the way for a major natural gas expansion at Georgia Power’s Plant Bowen, a massive coal-fired power plant roughly 40 miles northwest of downtown that could add hundreds of tons of new air pollution each year to a region already struggling with unhealthy air.

Environmental Groups Challenge Air Permit for Natural Gas Expansion at Atlanta Plant

Climate Change

War in Iran Could Have ‘Historic’ Disruptions on Energy Markets

Oil prices jumped after the United States and Israel attacked Iran. Experts say the effects on oil and gas prices will depend on how long the war lasts and whether Iran damages energy infrastructure.

The U.S. and Israeli war against Iran is disrupting energy markets and driving oil and gas prices higher in the United States and globally. While those increases are modest so far, experts say the war has the potential to cause more severe and lasting impacts if Iran damages the region’s energy infrastructure or restricts shipping through the Strait of Hormuz.

War in Iran Could Have ‘Historic’ Disruptions on Energy Markets

Climate Change

Analysis: Half of nations meet UN deadline for nature-loss reporting

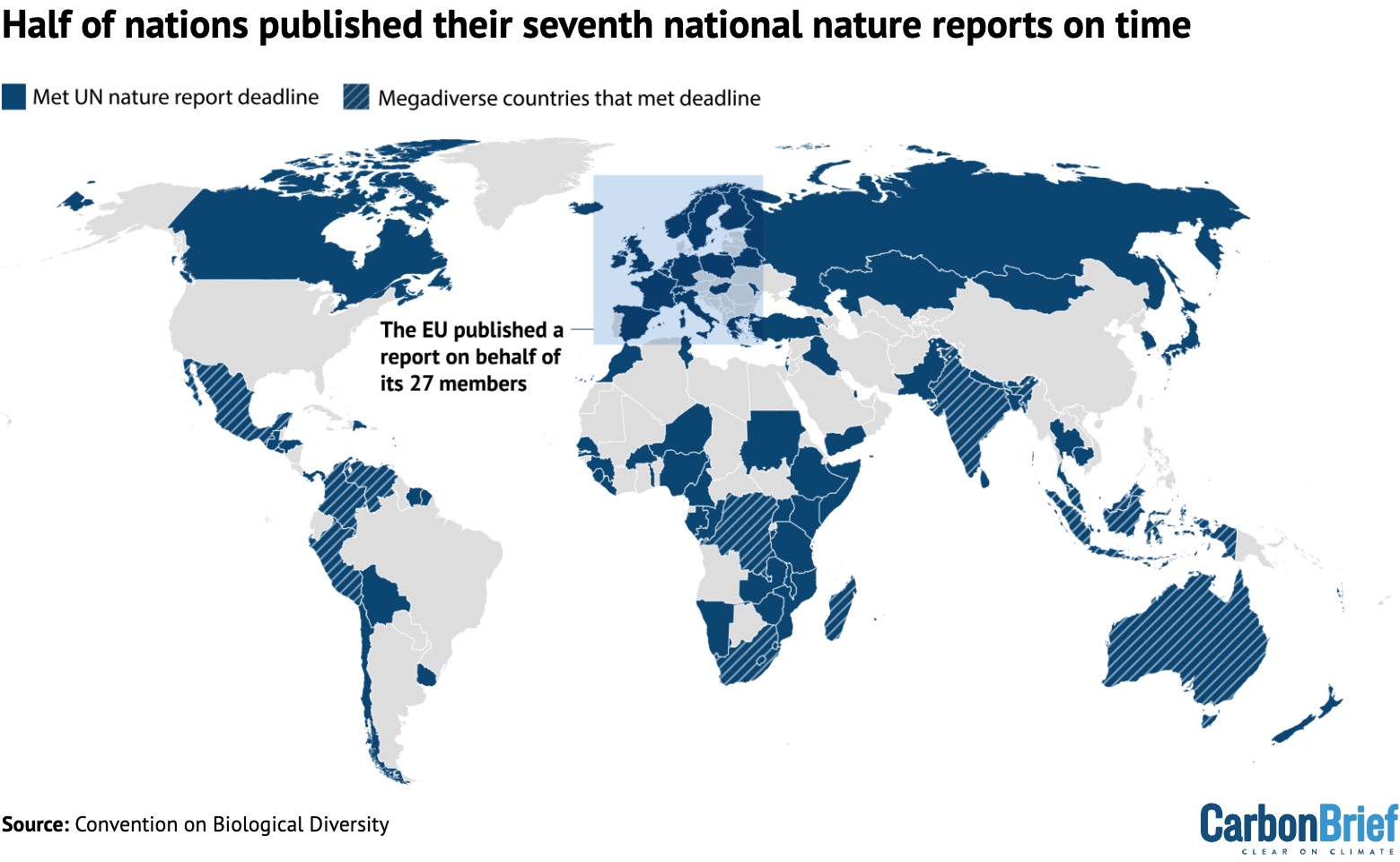

Half of nations have met a UN deadline to report on how they are tackling nature loss within their borders, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

This includes 11 of the 17 “megadiverse nations”, countries that account for 70% of Earth’s biodiversity.

It also includes all of the G7 nations apart from the US, which is not part of the world’s nature treaty.

All 196 countries that are part of the UN biodiversity treaty were due to submit their seventh “national reports” by 28 February, of which 98 have done so.

Their submissions are supposed to provide key information for an upcoming global report on actions to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030, in addition to a global review of progress due to be conducted by countries at the COP17 nature summit in Armenia in October this year.

At biodiversity talks in Rome in February, UN officials said that national reports submitted late will not be included in the global report due to a lack of time, but could still be considered in the global review.

Tracking nature action

In 2022, nations signed a landmark deal to halt and reverse nature loss by 2030, known as the “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework” (GBF).

In an effort to make sure countries take action at the domestic level, the GBF included an “implementation schedule”, involving the publishing of new national plans in 2024 and new national reports in 2026.

The two sets of documents were to inform both a global report and a global review, to be conducted by countries at COP17 in Armenia later this year. (This schedule mirrors the one set out for tackling climate change under the Paris Agreement.)

The deadline for nations’ seventh national reports, which contain information on their progress towards meeting the 23 targets of the GBF based on a set of key indicators, was 28 February 2026.

According to Carbon Brief’s analysis of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity’s online reporting platform, 98 out of the 196 countries that are part of the nature convention (50%) submitted on time.

The map below shows countries that submitted their seventh national reports by the UN’s deadline.

This includes 11 of the 17 “megadiverse nations” that account for 70% of Earth’s biodiversity.

The megadiverse nations to meet the deadline were India, Venezuela, Indonesia, Madagascar, Peru, Malaysia, South Africa, Colombia, Mexico, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Australia.

It also includes all of the G7 nations (France, Germany, the UK, Japan, Italy and Canada), excluding the US, which has never ratified the Convention on Biological Diversity.

The UK’s seventh national report shows that it is currently on track to meet just three of the GBF’s 23 targets.

This is according to a LinkedIn post from Dr David Cooper, former executive secretary of the CBD and current chair of the UK’s Joint Nature Conservation Committee, which coordinated the UK’s seventh national report,

The report shows the UK is not on track to meet one of the headline targets of the GBF, which is to protect 30% of land and sea for nature by 2030.

It reports that the proportion of land protected for nature is 7% in England, 18% in Scotland and 9% in Northern Ireland. (The figure is not given for Wales.)

National plans

In addition to the national reports, the upcoming global report and review will draw on countries’ national plans.

Countries were meant to have submitted their new national plans, known as “national biodiversity strategies and action plans” (NBSAPs), by the start of COP16 in October 2024.

A joint investigation by Carbon Brief and the Guardian found that only 15% of member countries met that deadline.

Since then, the percentage of countries that have submitted a new NBSAP has risen to 39%.

According to the GBF and its underlying documents, countries that were “not in a position” to meet the deadline to submit NBSAPs ahead of COP16 were requested to instead submit national targets. These submissions simply list biodiversity targets that countries will aim for, without an accompanying plan for how they will be achieved.

As of 2 March, 78% of nations had submitted national targets.

At biodiversity talks in Rome in February, UN officials said that national reports submitted late will not be included in the global report due to a lack of time, but could still be considered in the global review.

Funding ‘delays’

At the Rome talks, some countries raised that they had faced “difficulties in submitting [their national reports] on time”, according to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin.

Speaking on behalf of “many” countries, Fiji said that there had been “technical and financial constraints faced by parties” in the preparation of their seventh national reports.

In a statement to Carbon Brief, a spokesperson for the Global Environment Facility, the body in charge of providing financial and technical assistance to countries for the preparation of their national reports, said “delays in fund disbursement have occurred in some cases”, adding:

“In 2023, the GEF council approved support for the development of NBSAPs and the seventh national reports for all 139 eligible countries that requested assistance. This includes national grants of up to $450,000 per country and $6m in global technical assistance delivered through the UN Development Programme and UN Environment Programme.

“As of the end of January 2026, all 139 participating countries had benefited from technical assistance and 93% had accessed their national grants, with 11 countries yet to receive their funds. Delays in fund disbursement have occurred in some cases, compounded by procurement challenges and limited availability of technical expertise.”

The spokesperson added that the fund will “continue to engage closely with agencies and countries to support timely completion of NBSAPs and the seventh national reports”.

The post Analysis: Half of nations meet UN deadline for nature-loss reporting appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Half of nations meet UN deadline for nature-loss reporting

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits