Weather Guard Lightning Tech

HeliService USA: Efficient Offshore Wind Transportation

Allen and Joel speak with Michael Tosi, founder and CEO of HeliService USA, which is providing helicopter transportation for the offshore wind industry. HeliService USA provides efficient, safe, and environmentally-friendly transport for technicians and equipment to offshore wind farms, providing an advantage over marine vessels. With the highest safety standards, cost-effectiveness, and speed, HeliService is making offshore wind travel better.

Sign up now for Uptime Tech News, our weekly email update on all things wind technology. This episode is sponsored by Weather Guard Lightning Tech. Learn more about Weather Guard’s StrikeTape Wind Turbine LPS retrofit. Follow the show on Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, Linkedin and visit Weather Guard on the web. And subscribe to Rosemary Barnes’ YouTube channel here. Have a question we can answer on the show? Email us!

Pardalote Consulting – https://www.pardaloteconsulting.com

Weather Guard Lightning Tech – www.weatherguardwind.com

Intelstor – https://www.intelstor.com

Allen Hall: Welcome to the Uptime Wind Energy Podcast. I’m your host, Allen Hall, along with my co host, Joel Saxum. As offshore wind continues to develop in the U. S., transportation of technicians and equipment is becoming a big issue for developers and operators to tackle. HeliService USA provides helicopter transportation and support services for the offshore wind industry in the U.

S. Based in Rhode Island, the company is utilizing the unique capabilities of helicopters to deliver personnel, cargo, and equipment. and conduct maintenance operations efficiently. Our guest is Michael Tosi, founder and CEO of HeliService USA. Michael is a helicopter pilot and also served in the U S air force.

Michael, welcome to the show.

Michael Tosi: Thank you, Allen. Really appreciate you having me today and look forward to chatting more.

Allen Hall: You’re in a really busy place right now because the pace of construction on U. S. offshore projects has really picked up. And you’re flying technicians back and forth. How many flights are you conducting right now a week?

Michael Tosi: So it, it varies. There’s two big scopes that we cover. So the first scope we cover is actually the construction of the wind farm. For the construction of the wind farm, we’re typically flying offshore workers who are going to be on vessels for, two, three, four, five, six weeks, depending on what their shift schedule is.

So that involves flying out to an installation vessel, a heavy lift vessel S. O. V. potentially, depositing those passengers we usually bring folks back to the other direction. And so those flights go on per vessel, sometimes once a week, twice a week, per vessel in the field. And now, of course, because they have several turbines up, more than several at this stage we’re also helping with operations and maintenance even prior to the wind farms being completed.

We are actually going to be commissioning flights as well. To certain turbines. I think that’s the first time at least that I’m familiar with that certainly has probably occurred in Europe. But at least from what our customers tell us that some of the first times they’ve used helicopters for commissioning were as well on the turbine.

It can be a bit cyclical on the demand, depending on when the vessels are here or not. But just for some numbers, I think it’s a good thing. We’ve been in operation for about a year and transported over 6, 000 people offshore during that time. To my knowledge, I think we transported certainly more than any other with just 16 folks offshore.

So it’s been a busy year.

Joel Saxum: Let me ask you a question, Michael. What does it look like for a technician that’s going to go Fly out to a turbine for work. Do they arrive at your facility with all their gear ready to go? And five minutes later, they’re in a helicopter or how, what does that look like?

Michael Tosi: It’s a pretty quick process. It’s a little bit different for the folks who go offshore to construction vessels. They’re they use helicopters, not necessarily less, but there’s less flights. So a technician may go out every single day of his hitch. So if he has a 14 day schedule, you may go offshore with the helicopter 14 times out 14 times back.

Plus sometimes intra field work, so turbine to turbine, or SOV to turbine, you name it. So they may do, in a 14 day span, they could do over 30 flights, over 40 flights, depending on how you look at it. So they get very accustomed to working with our crews. I don’t want to say they’re part of the crew, they’re not technically part of the crew, but a lot of rapport builds up between our hoist operators, our pilots, the technicians, because they’re working with them intimately every single day which is pretty neat.

So when they show up Especially for the folks who fly with us all the time, who’ve been breathed and are ready, they have to watch a briefing video, but really, they just throw on their harness do the briefing video, which is a legality at that point, because of course, they’ve seen that many times before, but by FAA regulation, they have to watch it, get that video, head out to the helicopter, and they’re airborne pretty quick, so from the start of their day to, on a turbine is an hour or mass.

You’re talking a second team, an hour and 20 minutes or less to get them offshore. So it is extraordinarily quick from the point where they take off to the turbine depending on the project for at least the ones we serve now is about 13 minutes. So it’s an astonishingly quick. Can you, and if you’re on the helicopter, that goes really fast.

Allen Hall: And the big question, obviously, between CTVs and helicopters that always comes up is emissions and emissions are a big topic in the wind industry at the moment. Are helicopters more efficient from an emission standpoint than ship transports?

Michael Tosi: Drastically it’s not one of those things in the margins.

It’s not single digit percentages. You’re talking to orders of magnitude. The easiest way to think about it is assume exactly the same fuel burn rate, which is not necessarily the case. But assuming the exact same fuel burn rate, you’re taking 8 to 10 times as longer to do the same exact transportation.

So even if we burn twice, which we don’t, depending on the CTV, my understanding is we burn the same or less per hour of operation. And that CTV is out there potentially 24 7, certainly 12 hours that it’s running. Whereas for us, 13 minutes out, 13 minutes back. At the end of the day you’re talking collectively that helicopter rarely is going to fly for more than a couple hours a day.

Certainly not 12 depending on the busyness. So overall drastically more efficient. We expect to see as they start getting worked into bids and proposals, having to account for your missions and your O& M means is that helicopters will start to see a massive step up.

Allen Hall: There are some other training besides throwing your harness on that has to happen.

So you can go offshore. You want to describe what some of that is?

Michael Tosi: Yeah, certainly. So one of the biggest concerns that we see from folks who aren’t familiar with helicopter operations, helicopter hoist operations, it looks pretty dramatic. And you think military, you think search and rescue, you think Coast Guard.

What they do and what I’ve done in the military and what I continue to do part time in the Air Guard as a search and rescue pilot is drastically different than this kind of hoisting. This is, I don’t want to say vanilla per se, but it’s intended to be repeatable. It’s intended to be done. One of our customers looked across their entire fleet.

All of their operators do 20, 000 plus waste a year without incident. So it’s designed to work incredibly well and incredibly safely. And it does have the highest safety record or none in terms of access means to a turbine. That includes SOVs, Amplements, and CTVs. And with that, though, it is not tremendously complex to train a technician.

Even if they’ve never seen a helicopter before, they require one day of underwater egress training. So that’s if lord forbid, a helicopter were ever to ditch, how to get out of it from being upside down, anyone who’s ever worked in the Gulf. It’s probably done that before. Some people love it, some people hate it.

I will say that. Generally, 80 percent of the class thinks it’s one of the coolest things they’ve done. 20 percent never want to see that thing ever again. It can break either way, depending on your familiarity and comfort in water. I really enjoy it. The only thing I don’t enjoy is my sinuses after being upside down in a pool all day.

So that’s about one day. Very easy class to get through. Again, there’s almost no attrition in that. The next thing you need is a one day hoist course. So you come to our facility you go through the hoist course. You spend about three to four hours in the classroom. Then you go out and we hoisted the aircraft in the hangar.

So on level ground, basically, without an airborne. We then go out to a nice open area. So like a little grassy field or a taxiway, you do our voice there about three per. And then we go to, we have a little mock turban. It sounds very fancy. It’s really a context container with a turban, a nacelle basket or a hoist basket welded onto it.

Pretty basic, but it does the job really. Accurately simulates the turbine and that’s another maybe four hours. So you’re talking two days to become a hoist trained and qualified technician, at least in terms of helicopter operations. It was very basic.

Allen Hall: I had the privilege of visiting your facility in Rhode Island and watching that training happen.

It is impressive. And the consistency of which you move people around and drop them on top of the simulated turbine top. That is amazing to see because it would just as an outsider, like I’ve never been dropped from a helicopter before, but it, as a technician, you would think, oh, I’m swinging around.

I’m doing all this crazy stuff. It’s not. It’s very controlled. It is. And it’s very consistent. I was amazed at the. Accuracy and the steadiness of it. We were there on a day that wasn’t the greatest day. It was sunny outside, but it was a little bit breezy and boy the amazing skills of the pilots to put technicians.

And move them around and put them on specific places was really incredible to watch. And I attribute that to a number of things. One of them, you mentioned your military background, your facilities and your aircraft are spotless and everything that technician sees. Spotless. Is that part of the military background that you’re bringing in, into your business?

Michael Tosi: It probably factors. We, I’ve always said I don’t trust getting into a helicopter unless it’s immaculately clean. Cause you can’t keep it clean and you can’t keep your facilities clean. How well are you, can you, I really trust that you’re maintaining that helicopter. It’s the easiest thing to do is keep something clean.

Certainly compared to complex maintenance. We think it’s really important for our customers. They do pay very good money for the service and we expect it, always to be a magnet, to be clean, to be very professional. Certainly appreciate the confident we try. It’s it’s always a never ending battle, especially with white helicopters, as you might imagine, to keep clean, but you certainly know when they’re clean.

In regards to the precision Yeah, there’s a couple of factors in that one is just the inherent nature of the work to we do have very skilled pilots. So many of them are former search and rescue pilots, former military or civilian pilots are all come from very diverse and impressive backgrounds of doing external load work.

So if you’ve ever seen that the folks that look like they’re dancing with the helicopter when they have those, barrels under it or firefighting those guys, so they can really place it if you, I think there’s the, I forget the exact name of it, that childhood game twister where you have to put your, your different limb on a different, different little circle.

Our crews should be able to in 40 plus not wins deposit someone exactly on one of those circles. It’s not hard to get within just a single foot. Like we can say, Hey, we’re gonna put that guy exactly there. We actually use remote hook operations so we can pick up cargo. without someone necessarily there to hook it up.

What that requires is the pilot and the hoist operator work really closely together to basically hit a spot about that big with a magnet that then latches the hook on and comes up. So that gives you an idea of the level of precision that they have to be able to do. It’s a bit like the crane game except you’re 35 feet in the air with 40 knot winds.

And, it’s all very stable, very consistent. That’s it. They’ve always to make it look as effortless as possible.

Allen Hall: What is the ratio roughly of cargo transport versus technician transport? Are you doing mostly trans transportation of technicians at the moment?

Michael Tosi: It’s that the two typically go together.

There’s a couple of things we can talk about in terms of logistic strategies. There’s been some developments in recent years that I think break towards making helicopters increasingly more usable. But typically we’re taking technicians and the cargo out. By using remote hook operations, we can actually go out and pre position cargo.

So we can go leave cargo at the top of certain missiles. To pre position it so that way when the folks go out to work via any means, they could even get out via CTV, and that saves them the up and down time in the turbine. A variety of strategies that have been looked at and developed recently, but I’d say it’s a 50 50 mix.

For every technician, there’s typically a bag.

Joel Saxum: At the end of the day here, what helicopters bring to the game, you’re doing it safely, you’re doing it with less emissions, but you’re bringing efficiency. To operations, right? Whether it’s during commissioning or during service operations or whatever it may be moving tools, moving kit, moving people, you’re doing it more efficiently, right?

So there’s an option here. So I’ve done some helicopter operations in the past. When I did helicopter operations, it was because there was no other option. Like you’re not going to get there unless you use a helicopter. In the offshore world, there is an option. You can use a CTV. You can be on an SOV, a walk to work with an Ampleman or a crew transfer with a CTV, up the ladder and whatnot.

However, what you guys are doing is we talked about earlier orders of magnitude, more efficient. Now, if I’m, if I have a technician going to work, would I rather be paying them for six to seven hours of the day to sit on their butt in a CTV or would I, and then get there and then be able to work for four to five hours?

Or do I want them in the helicopter out there and putting a 10 hour shift in on that piece of equipment. So the cost starts to really balance out just by the more efficiency of the personnel in the field. And another thing too, it’s like when we talk with 3S Lift. You’re not beating these technicians up all day long, right?

They’re getting to work, their brains are ready to go, they’re not tired, they haven’t been bouncing around in a CTV all day on the way out there. They’re, less basically tired. They’re able to focus on their job more because they’re there to do a job. They get there, boom, arrive at your site, get on the bird.

They’re out there real quick and able to get to work. So you guys are not only making, the technicians hours more workable but you’re driving efficiency for the whole operation.

Michael Tosi: Yeah. And I think increasingly as helicopters become more prevalent, I think the industry is starting to see this, particularly as they wrestle with costs with contracts is.

The inertia the preconceived notions that folks have, just because that’s what they’ve always done doesn’t necessarily work anymore, particularly in the U S with the Jones act, the price of vessels, folks have been forced to like elsewhere. And to your point, it is ultimately efficiency.

I’ve yet to see the business that can waste its labor for 50 percent of the day with its people. And continue to be effective. You just can’t do that. It’s, it’s an employer. I’m always looking for every way that I can use any employee. And also employees enjoy it more employees, at least good employees that you have on your team don’t enjoy downtime.

They enjoy working and they enjoy being productive. They enjoy being efficient. It’s just adds to a better quality of life. And your point, just not sitting on a vessel, hammering away. For four, four hours each direction, or even three you’re talking four hours time on turbine versus you go via helicopter to any relatively near shore wind farm.

I’m talking nine to ten hours minimum time on turbine per day, which is a substantial portion of the workday.

Joel Saxum: One of the things that we have in offshore projects, there are, it’s a lot different than onshore projects, whether it’s wind, oil and gas civil project, anything, is There’s items defined in the scope is critical path.

And when you talk critical path, it’s things that like, unless this milestone is hit, or unless this part is here on time, or unless this gets done on this day, everything else behind it gets extended, everything else starts to lose their, it’s foothold in the timeline of getting the project built. And a lot of these projects are based on milestones, right?

So whether it’s an investment decision, when you’re going to get money, when the PPA starts, all of these different things, these projects need to stay on. Online and on board. So you have other things in the construction process that are. Up and moving. So a specialized wind turbine installation vessel, that vessel cannot get held up.

If that vessel gets held up, they’re hundreds of thousands of dollars a day and just day rate, right? So as HeliService, as a big part of this now booming industry, When someone calls you, I’m imagining that you guys are just like, yeah, we provide rides. It’s more of you you have conversations to be a partner.

You get in, you look at the logistics. How can we optimize this thing? How does that work? When someone engages with you guys.

Michael Tosi: Online via LinkedIn, wherever else our team is always going to be available for these types of discussions. But to your point, it’s a lot more education. It’s being a partner with the customer very early on.

And. No different than vessels or any other part of the project. Helicopters aren’t Uber. You don’t just get to call them, 15 days before your project starts, and expect them to show up. They’re, very expensive. Anywhere from 12 to, low 20 millions of dollars. Per helicopter, depending on the size and the type, so it’s an expensive asset that’s finance over a long time, and it’s really important that gets integrated to a project early because there’s a lot of synergies throughout construction as you talked about O and M and also emergency rescue services, and you can use that helicopter for three.

If you really segmented and talk really quickly or speak really quickly before the project you lose a lot of the economies of scale that it costs more, and there may not be any availability. So what we like to do is speak with customers very early. Certainly more than two years out.

Hopefully, four to five years out as they’re looking at their entire logistics concept. And we’ll come in and get involved with them. We’ll do case studies where we take a look at it. Try and back up their data. It’s just to facilitate the discussion. We all know that a case study isn’t necessarily perfect.

There’s a lot of real world aspects to it, but we can talk about those with helicopters. A lot of folks in the industry almost always have green affairs or folks with vessel background in their on their teams. And a lot of them don’t necessarily have helicopter expertise on the team. And so there’s a lot of preconceived notions, be it about the safety, be it efficiency, be it lead time, the ability to call up and expect a service.

Most offshore wind has existed in an area with a built up offshore infrastructure. So in Northern Europe, where you had oil and natural gas work, you have a lot of operators. Here, there’s not just that excess capacity, and there won’t be for a long time. So folks need to have those conversations early.

And again, we like to sit there and look holistically at the project. We mentioned construction. Construction is the one where we see the least amount of debate. Almost all the tier one companies understand the need for helicopter operations. I haven’t spoken with a single one that would not prefer to use helicopters because for your, to your point, that asset is so enormous enormously expensive and also enormous size wise.

They, that goes down and it’s not just the vessel that costs the most. Four or five, six, 700, 000. It’s the entire operation, because it is all revolving around that one vessel. So if that vessel goes down, be it because the crane operator is sick, they need the 5 bolt. Gotten many of those phone calls.

Yeah, we need this now. I’ve learned about a couple professions I want to get into, because sometimes we’ll get a desperate call to get someone offshore. And they’re like, no, this is the only guy in the world who can do this. And I was like you mean the only guy in the world? I’m like, that guy sounds like he has great salary negotiating power.

Like, how do I sign up for that job?

Joel Saxum: To your point, I’ve been a part of oil and gas operations where they have to bring a tool or a part or a piece to a platform in the gulf 80 miles away. So this 100 piece now costs 10, 000 because it has to be there now. And if you were to put it on a vessel, you would keep that whatever it is, offshore drilling rig, offshore platform, you’d keep that thing on stall.

For a day. Now you’ve got a helicopter, you dispatch it out of OMA and it’s there, the parts there in a couple hours. So like the difference is amazing.

Michael Tosi: Or you just don’t have access for seven to 10 days. There’s, there was a stretch here where a couple of the jackups out there doing installation did not have the ability to get an SOV or a CTV out there for seven days straight.

And if you don’t have a helicopter to access that installation vessel the entire project, the installation vessel is. A couple hundred thousand a day, which is not a chump change, the entire operation, probably even worth the 5 million a day. And so at that point, helicopter, I was paid for itself in a single day.

I can anecdotally tell you points that every single major wind farm that we’ve worked on, which is the entire Northeast cluster, where we have single handedly paid for ourselves. It’s not hard anecdotally, let alone with the case study, but we obviously like to go through all of that start to finish.

Joel Saxum: And we’re talking, what about weather windows, right? So when you’re on a CTV there or an SOV, there’s always a wave height weather window. And I don’t know exactly what they are because they’re different for each vessel.

Michael Tosi: We, we can get out there right up to our limits our 45 knots depending on, we have some slightly different configurations, the helicopter 45, sometimes up to 60 with one of the helicopter configurations, obviously I’d get to meet the technician or The company that would like to be deployed in 60 knot winds.

However, we do frequently waste up to 40. I’ve been out there wasting technicians at 40 knot winds. And it’s again, on the pilot side, it’s a little bit of work, but that’s why we pay the pilots, the, the big bucks is to do that. Do it well and do it safely. And to answer your other question, I think this actually does hit on a key point.

I think this is a little, I don’t want to say it’s a source of friction, but for folks coming from the maritime world, they’re very used to looking at a schedule for seven days and they know. For better or worse, what that next seven days is going to look like now, the downside of it, particularly in the winter is you may not be able to go out for seven days we’ve seen on the projects in the Northeast.

I’ve seen frequent stretches of seven days or more where there hasn’t been a single S O V or CTV. This January and February, there was at least three, at least two, if not three stretches where they saw seven days with no CTV access or SUV access. And if you look at loss production and that’s where it really comes to the efficiency.

That’s where the numbers really make sense. As these turbines get bigger and bigger every hour, they’re down as an enormous amount of money. And then is it? It cascades, say you are planning a ton unscheduled per year, you got 60 turbines so you call it just to make the numbers a little easier, closer to 70.

You’re talking over the given day, you’re going to see somewhere between three to five on schedule down down turbines. Now multiply that over seven days, but in the end of seven days, you’re looking at 20 turbines that are down and not producing to the tune of Certainly six figures, but all my math suggests seven figures or more you’re losing per, yeah, per day.

Oh, it’s seven figures for sure.

Joel Saxum: Yeah, because I mean you’re looking at, okay, so if we’re, say we talk about a 10 megawatt turbine, if you’re saying it operated 24 hours at 150 an hour PPA, that’s 35, 000 ish per turbine per day.

Michael Tosi: Like you said, into the seven figures, you’re talking that in those three stretches of land here in the northeast, you could pay for, easily pay for a helicopter if not two without question.

And it’s the fact that there’s still projects that go in. And expressly say they’re not going to use helicopters for O& M is astonishing. And I don’t think that will last for long.

Joel Saxum: No. Cause if you’re talking a 30 knot sustained wind at sea, this wind flex, say some South Fork is it 35 miles offshore or so?

Michael Tosi: About it’s a little bit different from Rhode Island, Block Island, and the Vineyard. It’s equidistant, but approximately.

Joel Saxum: But when you get out that far in the ocean, you’re going to have, if you have sustained 30 knot winds, you’re going to have Fifteen to twenty foot waves? You’re not transferring on a CTV in that kind of wave height, like it, it’s just it’s unsafe.

So that’s, there’s going to be HS, safety limits on that. However, you guys could still be bringing people to work on the helicopters.

Michael Tosi: Yeah, but, and there’s also limits on SOVs. That’s another common fallacy is that SOVs are some sort of placebo. And I’m also not going to tell you helicopters run every single day of the year either.

But what you don’t see with helicopters is you almost never see, Combined stretches of more than a day without being able to fly. So you never get that cascading effect. Because for us, the only thing that really keeps us in the ground is essentially fog. Or lower cloud decks or some sort of, very significant convective activity that will keep us in the ground.

But I really don’t remember the last time that we had more than one day. And very often, it’s You know, there’s a morning you can’t fly, but for folks who are used to marine planning, I do sense that’s a little bit of, a little bit of friction there, a little consternation because they want to plan their week out before.

And with the helicopter, it could be very much like hour by hour. Now of course, what you look at, I’m sure it’s hour by hour, but you waited four hours to take off in the morning, but you still got more time in turban that had you taken the CTV. Early in the morning and your workers show up ready to work because they were able to relax for the morning and went out Really quickly.

So I think the benefits just far outweigh that and so overall accessibility rates for helicopters are well over 90 percent I’ve never seen an operator or operation where you don’t see 90 percent or greater Whereas CTV access rates in the winter 30 40 percent at best year round 60 70 even if it was 80, there’s still a substantial Delta.

Allen Hall: So I would imagine, Michael, that there’s standards for operating offshore, particularly around wind turbines versus something onshore, like helicopter delivery service, crop dusting, those kinds of things. There’s just a completely different thing. What are some of those standards that you have to meet in order to do this work?

Michael Tosi: It’s a great question. As with any industry working offshore particular but also any industry that’s Very often the regulatory standard is not sufficient for safe operations, and aviation is 100 percent that way. I could safely operate, offshore not safely, I could buy a regulatory standard.

I could take your local tour helicopter, like a very small 400, 000 helicopter powered by what sounds like a, a 65 Chevelle engine. Fire that thing up. With no floats, no life raft, no anything. Just give the guy all that’s required by regulation is that I give the passengers a little vest.

I can fly that offshore to a 300 million vessel that is completely permissible by the regulation. Needless to say, the industry cannot count on the regulations to ensure a safe operation. So a lot of the more sophisticated players have folks with an aviation background to help audit suppliers and all of the OEMs.

So bestest GE and SGRE, I’m a team that comes in audits. All of the offshore helicopter operators that are flying their personnel out to a wind service. That’s the first start. But what they audit to is a specific set of industry standards. So how the offshore. Has standards, wind recommended procedures, wind rep, and then also IOGP is not directly, it’s not directly translate, but it’s pretty close.

Those two are not very far off. And if operator is living up to IOGP standards, it’s it’s very easy to get up to the Helios for standards or vice versa. So either way you’re looking for an operator that flies to those standards and is audited by the team of OEMs, that’s the best way to do it.

And of companies in the world that meet that standard, it certainly takes less than two hands worth of fingers to list off those companies. So maybe a little over a half dozen around the world that can successfully do this. It’s a complex job. There’s an incredible safety record. I don’t like to say it because they don’t want to jinx it, but it sounds awful lot like zero in terms of fatalities.

The industry needs to keep that up. To continue to build faith in our access means and we as helicopter operators strive to do that every day. So it’s it’s critically important that operators be at, or sorry, tier ones and developers adhere to those standards.

Allen Hall: Oh, let’s touch on the safety aspect. And we have been talking on the podcast about. Offshore wind injuries, technicians getting hurt on site, particularly during the construction phase, we have a lot of big heavy equipment around big blades, tower sections, nacelles moving around and cranes people get hurt is their part of, or is there a standard or something for emergency services to fly people back and forth that may have been injured on the job?

Michael Tosi: No, unfortunately not. That’s That’s I want to say it’s short subjects for the industry, but it’s something the industry needs to look at very closely to my knowledge right now on the east coast. This is the only area in the developed world where there is offshore construction going at a substantial level.

Thousands of people offshore right now working where there is no commercial service, none. And the Gulf of Mexico has learned that the hard way. They learned that they needed to have a commercial service. They spend tens and tens of millions of dollars to run that commercial program in the Gulf.

To provide basically commercial search and rescue and EMS services for workers injured offshore. My team’s intimately acquainted with it. My director of ops and director of maintenance were very senior managers in that program as a chief pilot and SAR program manager. So they understand intimately why those exist, because they’ve done those calls.

They’ve seen those calls. And while the Coast Guard is a great backup, and it’s a wonderful organization, I have people who are alive because of the Coast Guard. Friends from my line of work in the military. Unfortunately, they’re not a commercial service, and they are not here to serve a specific industry.

And their ability to deliver high level medical care is non existent. They know it. They say it. I was at a G plus meeting and the Coast Guard District 1 rep says one covering the Northeast said that if you are counting on the Coast Guard as your primary means of medevac, you are setting yourself up for failure.

That is directly to the industry, spoken as clear as day. Fortunately, we’re starting to see some traction starting to see some discussion on it. So I think that message has been heard. And I think that will change very quickly here, which is exciting. But it is certainly something that the industry needs to take to heart.

Oil and natural gas, certainly understand is maybe I don’t want to say different core values, certainly from maybe political dispositions there’s a reticence to listen, it’s viewed as this sort of dirty oil and natural gas. Those folks knew how to do work offshore, they know how to do it extremely safely.

Yeah. There’s a lot of lessons to be learned about offshore health and safety from the oil and natural gas industry that they, they’re certainly not perfect but I would say they are, in fact, ahead of offshore wind by a substantial margin. I think the data backs that out.

Allen Hall: And Michael, you’ve chosen the Leonardo AW169 for your fleet, and the safety record of that aircraft is excellent. And what benefits does that helicopter bring to your service? And just by, just as a note. We did take a ride in the 169. That is a magnificent aircraft, by the way.

Michael Tosi: I appreciate it. No we’re I always joke, the helicopter industry is it’s a lot of fun to work in.

It’s not the best way to make money, selling software is probably a better way. It’s very capital intensive. It’s it’s a very high standard that you have to perform to. That you’re expected to because without saying aviation, you have every regulator imaginable there.

You have customers. It’s complex work. So very difficult business in general, but we do love, the fun part of the day is opening the hangar door and just looking at that, looking at the helicopters because they are certainly beautiful and extremely high performing.

And the reason that we go with the Leonardo AW169 specifically, it’s because of its hoist performance and its single engine safety margin. Just for everyone’s reference the safety margins built into this are absolutely incredible. This helicopter is able to, anytime we’re conducting a hoist with live human beings on the hoist, we’re able to have a single engine failure.

In the hover out of ground effect. I won’t go into advanced helicopter aerodynamics, but basically the higher up you go over a certain altitude, it starts to stay the same, but over about 50 to a hundred foot hover. It takes a lot more power than hovering about 10 feet off the ground. So it’s like the worst power state is you could be in.

If we have an engine failure out there at 380 feet, we can sit there for two and a half minutes and nothing changes. So you could be on the turbine, throw a wrench in the engine. Completely eats itself and the other engine will just fold it there for two and a half minutes and then you can clean up the hoist fly away just for reference cleaning up a hoist or terminating it to like quite quickly in a safe manner takes maybe five seconds.

So that two and a half minutes is an eternity. You can have an entire conversation. You could eat half a sandwich. That is a long time. So it’s an enormous amount of margin and then furthermore That margin allows me at all regimes of flight to be incredibly safe. So you always have a single engine performance to give you some reference, the military helicopters.

I fly, which are very impressive, very large, very powerful. I never have that power margin. I never had that performance. I can’t do that on the ground with no fuel. So even when I’m completely empty in the PAPOC helicopter and I’m hovering at 10 feet, by losing engine, we’re going to go right down on the ground.

So that’s the Delta in performance is pretty incredible. The 169 is really the only helicopter that has that level of power, and then it also enables us to do crew change because it has a nice big cabin with eight passengers. We can go off and also support construction during the same phase, whereas the H145 just similar, it’s over my head, I have time flying that aircraft, love the aircraft, it’s a really great aircraft, especially for EMS operations.

For offshore wind, it doesn’t allow us to do the diversity of mission stats or have the same power. Now, certain companies use it and in a certain circumstance, it can work, but the one six die is unquestionably the best civilian helicopter on the market for offshore wind without question.

Allen Hall: How many helicopters you have in service at the moment?

Michael Tosi: So right now we have three in active service supporting all of these projects they’re all pretty busy. Right now we have two separate bases. We have one on Martha’s vineyard to service the vineyard wind project. And then we also keep one, it wants it to serve as South Fork, Rev, Sunrise and Block Highlands.

Which was very excited to get pulled into that or under that umbrella because they were very excited to find out about that access meets which was, it was pretty cool. We got a very quick phone call from when they found out about it. So we’re excited to, to start working that hopefully relatively soon.

And then we keep our extra helicopter there at Quonset. So anytime we have to plus up for extra demand or we need to rotate one in for heavy maintenance, we can cycle that in.

Allen Hall: And what happens as the wind industry moves further south, like in Virginia, the offshore project there, and as we move all the way down to South Carolina, are there expansion plans?

Already in place?

Michael Tosi: For us. Absolutely. I say there isn’t a substantial project. There’s a lot so I can’t say 100%, but I’m pretty sure we’ve talked to or been involved in some fairly detailed discussions for nearly all of them. And I think. Particularly in the U. S. There is more of an aviation culture.

Europe, there’s not a general aviation culture. It’s not in the blood. If you like, obviously, people are certainly open to it there. But in the U. S. People are very receptive. It’s just part of sort of normal business in the U. S. And so I think there’s a lot more. Open mindedness.

Also, some of the all the factors we talked about, Europe grew up a smaller winter, but it’s close to shore for the U. S. It’s right in the deep end. On the intended. I don’t know. For me, maybe when they get to the West Coast and floating window will be a little more in the deep end.

But either way I think people are very open to it. And we’ve talked to nearly every project. So I wouldn’t very much expect to see helicopters and hopefully continually HeliService USA helicopters moving further south.

Allen Hall: How do companies needing to transport technicians get a hold of you?

Michael Tosi: Yeah, our website, or certainly reach out directly to you folks or anyone else. We hopefully have enough contact for our website to get a hold of us. And Very responsive sales and business development team that certainly hungry to continue growing. We’re we very much enjoy our current operation and love the area.

It’s a wonderful place to be based up here in new England. We’re certainly here to continue to grow and hopefully serve the industry for a long time to come.

Allen Hall: Michael, thank you so much for being in the podcast and thank you for allowing us to visit your facilities. They are immaculate.

Michael Tosi: Very much appreciate it.

You guys are always welcome. I know you’re pretty close neighbors up here in New England. Hopefully we’ll see you again soon.

https://weatherguardwind.com/heliservice-usa-offshore-transportation/

Renewable Energy

Homeschooling

Decent and intelligent people respect the rights of parents to homeschool their children, but there are two reasons for concern: a) socialization, failure to expose children to their peers, so that they may make friends and come to understand the norms of society, and b) the quality of the education itself.

Almost all homeschooling in the United States is conducted on the basis of a radical rightwing viewpoint, normally a blend of evangelical Christianity and Trumpism.

Renewable Energy

The Positive Effects We’ve Had on Others Are Profound, Whether We Know It or Not

There’s a theory that most people underestimate the positive effects they’ve had on other people.

There’s a theory that most people underestimate the positive effects they’ve had on other people.

Yes, that’s the theme of “It’s a Wonderful Life,” but it’s also the core of the 1995 film “Mr. Holland’s Opus,” in which a music teacher who deemed that his life had been a failure because he never completed writing a great symphony, is gently and beautifully corrected. Please see below.

The Positive Effects We’ve Had on Others Are Profound, Whether We Know It or Not

Renewable Energy

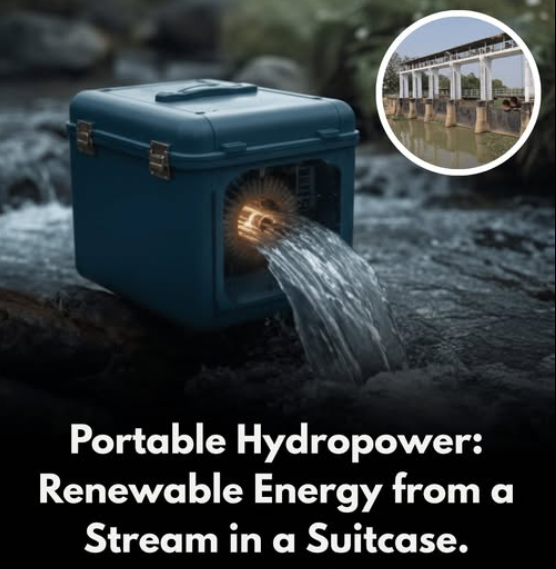

Renewable Energy Concepts Can’t Violate the Laws of Physics

In the early days of 2GreenEnergy, my people and I were vigorously engaged in finding solid ideas in cleantech that needed funding in order to move forward.

In the early days of 2GreenEnergy, my people and I were vigorously engaged in finding solid ideas in cleantech that needed funding in order to move forward.

I vividly remember a conversation with a guy in Maryland who was trying to explain the (ostensible) breakthrough that he and his team had made in hydrokinetics. When I was having trouble visualizing what we was talking about, he asked me to “think of it as a river in a box.”

“Oh!” I exclaimed. “You mean you take a box full of standing water, add energy to it get it moving, then extract that energy, leaving you with more energy that you added to it.”

“Exactly.”

I politely explained that the laws of physics, specifically the first and second laws of thermodynamics, make this impossible.

He wasn’t through, however, and insisted that, in his office, his people had constructed a “working model.”

Here’s where my tone descended into something less than 100% polite. I told him that he may think he has a working model, but he’s wrong; if he believes this, he’s ignorant; if he doesn’t, but is conducting this conversation anyway, he’s a fraud.

“But don’t you want to come see it?” he implored.

“No. Not only would not fly across the country to see whatever it is you claim to have built, I wouldn’t walk across the street to a “working model” of something that is theoretically impossible.”

—

I tell this story because the claim made at the upper left is essentially identical. You’re pumping water up out of a stream, and then claiming to extract more energy when the water flows back into the stream.

Of course, social media today is rife with complete crap like this. We’ve devolved to a point where defrauding money out of idiots is rapidly replacing baseball as our national pastime.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits