The retreat of sea ice in the Arctic has long been a prominent symbol of climate change.

Observations reveal that Arctic sea ice extent at the end of summer has halved, since satellite records began in the late 1970s.

Yet, since the late 2000s, the pace of Arctic sea ice loss has slowed markedly, with no statistically significant decline for about 20 years.

In new research, published in Geophysical Research Letters, my colleagues and I explore the reasons for the recent slowdown of Arctic sea ice – and turn to climate models to understand what might happen next.

Our findings show that, rather than being an unexpected or rare event, climate model simulations suggest we should expect periods like this to occur relatively frequently.

This current slowdown is likely caused by natural fluctuations of the climate system – just as they played a part in an acceleration of sea ice loss in the decades prior.

Were it not for human-caused warming, it is likely that sea ice would have increased over this period.

According to our simulations, the slowdown could even last for another five or 10 years – even as the world continues to warm.

Widespread slowdown

The changes in the Arctic are one of the most clear and well-known indicators of a warming climate.

With the Arctic warming up to four times the rate of the global average, the region has lost more than 10,000 cubic kilometres of sea ice since the 1980s. (The volume of ice lost is roughly equivalent to 4bn Olympic swimming pools).

Arctic sea ice reached its smallest extent on record in September 2012, dwindling to 3.41m square kilometres (km2). This triggered discussions of when the Arctic might see its first “ice-free” summer, where sea ice extent drops below 1m km2.

Research has shown that human-caused warming is responsible for up to two-thirds of this decline, with the remainder down to natural fluctuations in the climate system, also known as “internal climate variability”.

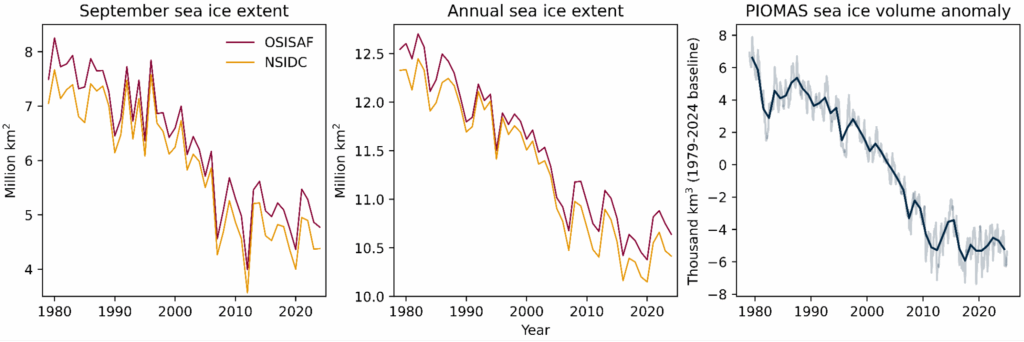

Despite the record low of 2012, satellite data reveals a widespread slowdown in Arctic sea ice loss over the past two decades.

Climate model simulations of Arctic sea ice thickness and volume further reinforce these observations, indicating little or no significant decline over the past 15 years.

This data is laid out in the charts below, which show average sea ice extent in September (left) and for the whole year (middle), as well as how annual average sea ice volume differs from the long-term average (right).

(September is typically the point in the year where sea ice reaches its annual minimum, at the end of the Arctic summer.)

The coloured lines indicate that the data originates from the National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC, orange), the Ocean and Sea Ice Satellite Application Facility (OSISAF, red) and the Pan-Arctic Ice Ocean Modeling and Assimilation System (PIOMAS, blue).

These observational records show how the precipitous decline in sea ice seen over much of the satellite data has slowed since the late 2000s.

It also shows that the slowdown is not limited to summer months, but is occurring year-round.

Our study is not the first to highlight this slowdown – several recent studies have also examined various aspects of this phenomenon. Meanwhile, a 2015 paper was remarkably prescient in suggesting such a slowdown could occur.

Is the slowdown surprising?

The loss of sea ice around the north pole is both a cause and effect of Arctic amplification – the term given to the rapid warming in the region.

Melting snow and ice reduces the reflectiveness, or “albedo”, of the Arctic’s surface, meaning less incoming sunlight is reflected back out to space. This causes greater warming and even more melting of ice and snow.

This “surface-albedo feedback” is one of several drivers of Arctic amplification.

Given global warming is caused by the continued rise in greenhouse gas emissions, it might seem puzzling – or even impossible – that Arctic sea ice loss could slow down.

However, the recent generations of climate models used for the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) – the international modelling effort that feeds into the influential reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – illustrate why this might be happening.

Models from CMIP5 and CMIP6, which simulate the historical period and explore different future warming scenarios, indicate that slowdowns in Arctic sea ice loss lasting multiple decades are relatively common – happening in roughly 20% of model runs.

This is due to natural variability in the climate system, which can temporarily counteract decline of sea ice – even under high-emission scenarios.

One way that climate scientists investigate natural variability is by running multiple simulations of a model, each with identical levels of human-caused emissions of carbon dioxide, aerosols and methane. These are known as “ensembles”.

Due to the chaotic nature of the climate system, which results in different phases of natural variability, the different model runs produce different outcomes – even if the long-term climate change signal from human activity remains constant.

Large ensembles help us to understand how to interpret the Earth’s observed climate record, which has been influenced by both human-induced climate change and natural variations.

In our research, we examine how many individual model runs within the ensemble exhibit a similar or greater slowdown in sea ice loss than the observed record over 2005-24.

The models show that natural climate variability can accelerate sea ice loss, as seen during the dramatic record-lows in 2007 and 2012. However, this natural variability can also temporarily slow the longer-term downward trend.

The primary suspects behind this multi-decade variability are natural fluctuations linked to the tropical Pacific and the North Atlantic, although the precise causes are yet to be quantified.

For example, a shift from the positive, warm phase to the negative, cool phase of a natural cycle in the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation is associated with bringing much cooler waters close to the North American coastline and into the Arctic. This could potentially lead to sea ice growth.

What might happen to Arctic sea ice cover next?

So how long could this current slowdown persist?

Climate model simulations suggest the current slowdown might continue for another five or 10 years.

However, there is an important caveat: slowdowns like this often set the stage for faster declines later.

Climate models suggest that when the slowdown inevitably ends, the rate of sea ice loss could rapidly accelerate.

Thousands of simulations analysed in our research reveal that September sea ice loss ramps up at a rate of more than 500,000km2 per decade after prolonged periods of minimal sea ice loss.

This would equate to more than 10% of current sea ice cover in September.

An analogy of Arctic sea ice extent behaving like a ball bouncing downhill – set out in a 2015 Carbon Brief article by Prof Ed Hawkins – is particularly apt here.

Just like the ball – which eventually reaches the bottom due to gravity, despite an erratic journey – Arctic sea ice loss may temporarily seem to defy expectations at present.

Ultimately, however, sea ice loss will resume, reflecting the underlying human-induced warming trend.

While it may seem contradictory that Arctic sea ice loss can slow even as global temperatures climb, climate models clearly show that such periods are expected parts of climate variability.

As a result, the recent slowdown in Arctic sea ice does not signal an end to climate change or lessen the urgency of cutting greenhouse gas emissions, if global goals are to be met.

While the current slowdown might persist for some years to come, when sea ice loss resumes, it could do so with renewed intensity.

The post Guest post: Why the recent slowdown in Arctic sea ice loss is only temporary appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Guest post: Why the recent slowdown in Arctic sea ice loss is only temporary

Climate Change

Greenpeace Australia Pacific response to the Middle-East crisis

Like so many people around the world, I am experiencing a sense of horror at the escalating violence in Iran and the Middle East. Greenpeace has called for all parties to immediately halt further military action, for international law to be fully upheld, and for a return to diplomacy to stop the suffering of civilians. The people of Iran, and all people, everywhere, have the inalienable right to live free of violence, fear and coercion. As humans we grieve for lives lost, and for all those who suffer.

But while countless people experience the consequences of this latest mass violence, some interests will no doubt attempt to benefit from the crisis. We can expect that fossil fuel corporations and lobbyists will cynically use the closure of the Strait of Hormuz-a major shipping route for oil and gas-to propagandise for increased fossil fuel production.

The practical reality is that a country as rich in renewable sources of energy as Australia should not be hostage to the global fossil fuel trade. The pursuit of fossil fuels–coal, oil and gas–have been the source of vast scale conflict, violence and geopolitical volatility for far too long. This will only accelerate as the climate crisis–itself driven primarily by fossil fuel extraction and burning–continues to put greater pressure on natural and social systems.

The truth is that the only absolute way to provide true energy security for the world is to phase out fossil fuels rapidly and deliberately, at emergency speed and scale, and to accelerate the shift to modern, renewable energy.

It’s in the strategic interest of all countries, including Australia, to unhook from volatile sources of energy. As long as our world runs on oil and gas, our peace, security and our pockets will always be at the mercy of geopolitics. As Professor Hussein Dia argued in The Conversation yesterday, this latest war in the Middle East shows why quitting oil is more important than ever.

These events are another jarring reminder that Australia doesn’t need more fossil fuel investment–we need less.

Locally controlled renewables are the best way to address the structural vulnerability at the heart of this recurring crisis. Ultimately, our freedom and security, prosperity and sustainability, are all best served by shifting from fossil fuels to renewable energy.

Dependence on fossil fuels makes all of us hostage to geopolitics and the whims of tyrants.

Greenpeace Australia Pacific response to the Middle-East crisis

Climate Change

Environmental Groups Challenge Air Permit for Natural Gas Expansion at Atlanta Plant

The Sierra Club and Southern Environmental Law Center are suing over state regulators’ approval of new gas turbines at Plant Bowen, citing concerns about worsening air quality.

Atlanta has spent decades battling smog and air pollution. Now, state regulators have cleared the way for a major natural gas expansion at Georgia Power’s Plant Bowen, a massive coal-fired power plant roughly 40 miles northwest of downtown that could add hundreds of tons of new air pollution each year to a region already struggling with unhealthy air.

Environmental Groups Challenge Air Permit for Natural Gas Expansion at Atlanta Plant

Climate Change

War in Iran Could Have ‘Historic’ Disruptions on Energy Markets

Oil prices jumped after the United States and Israel attacked Iran. Experts say the effects on oil and gas prices will depend on how long the war lasts and whether Iran damages energy infrastructure.

The U.S. and Israeli war against Iran is disrupting energy markets and driving oil and gas prices higher in the United States and globally. While those increases are modest so far, experts say the war has the potential to cause more severe and lasting impacts if Iran damages the region’s energy infrastructure or restricts shipping through the Strait of Hormuz.

War in Iran Could Have ‘Historic’ Disruptions on Energy Markets

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits