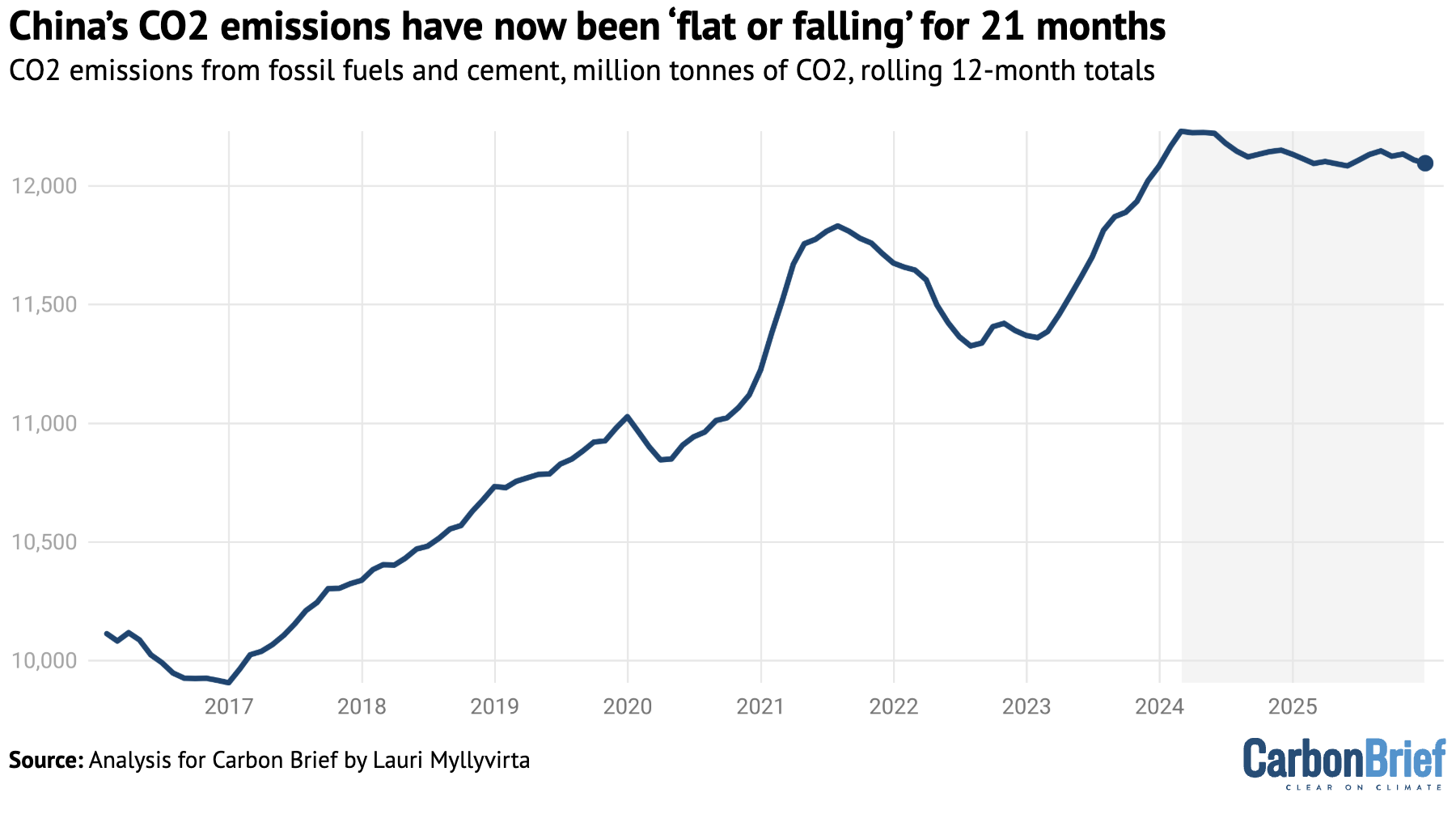

China’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions fell by 1% in the final quarter of 2025, likely securing a decline of 0.3% for the full year as a whole.

This extends a “flat or falling” trend in China’s CO2 emissions that began in March 2024 and has now lasted for nearly two years.

The new analysis for Carbon Brief shows that, in 2025, emissions from fossil fuels increased by an estimated 0.1%, but this was more than offset by a 7% decline in CO2 from cement.

Other key findings include:

- CO2 emissions fell year-on-year in almost all major sectors in 2025, including transport (3%), power (1.5%) and building materials (7%).

- The key exception was the chemicals industry, where emissions grew 12%.

- Solar power output increased by 43% year-on-year, wind by 14% and nuclear 8%, helping push down coal generation by 1.9%.

- Energy storage capacity grew by a record 75 gigawatts (GW), well ahead of the rise in peak demand of 55GW.

- This means that growth in energy storage capacity and clean-power output topped the increases in peak and total electricity demand, respectively.

The CO2 numbers imply that China’s carbon intensity – its fossil-fuel emissions per unit of GDP – fell by 4.7% in 2025 and by 12% during 2020-25.

This is well short of the 18% target set for that period by the 14th five-year plan.

Moreover, China would now need to cut its carbon intensity by around 23% over the next five years in order to meet one of its key climate commitments under the Paris Agreement.

Whether Chinese policymakers remain committed to this target is a key open question ahead of the publication of the 15th five-year plan in March.

This will help determine if China’s emissions have already passed their peak, or if they will rise once again and only peak much closer to the officially targeted date of “before 2030”.

‘Flat or falling’

The latest analysis shows China’s CO2 emissions have now been flat or falling for 21 months, starting in March 2024. This trend continued in the final quarter of 2025, when emissions fell by 1% year-on-year.

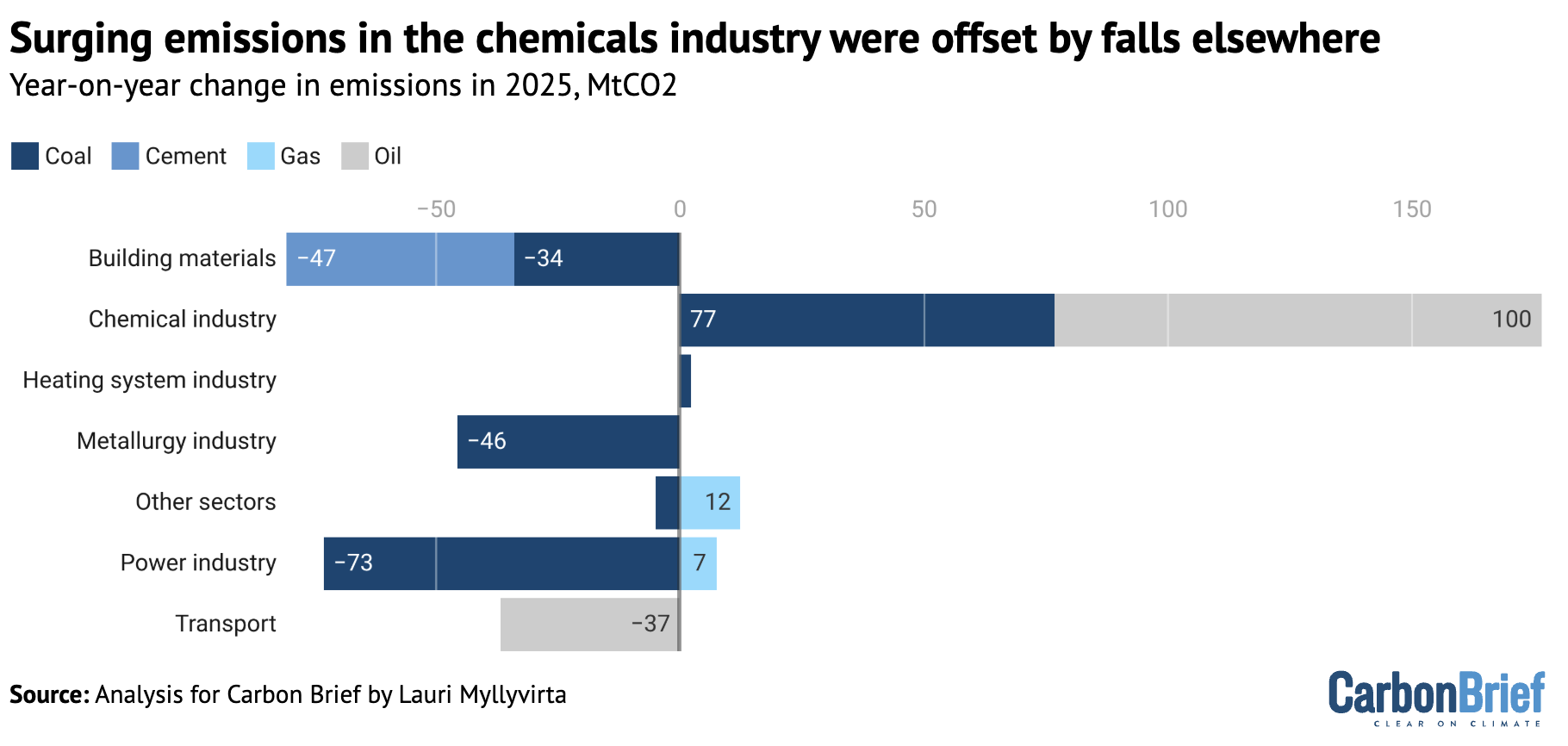

The picture continues to be finely balanced, with emissions falling in all major sectors – including transport, power, cement and metals – but rising in the chemicals industry.

This combination of factors means that emissions continue to plateau at levels slightly below the peak reached in early 2024, as shown in the figure below.

Power sector emissions fell by 1.5% year-on-year in 2025, with coal use falling 1.7% and gas use increasing 6%. Emissions from transportation fell 3% and from the production of cement and other building materials by 7%, while emissions from the metal industry fell 3%.

These declines are shown in the figure below. They were partially offset by rising coal and oil use in the chemical industry, up 15% and 10% respectively, which pushed up the sector’s CO2 emissions by 12% overall.

In other sectors – largely other industrial areas and building heat – gas use increased by 2%, more than offsetting the reduction in emissions from a 3% drop in their coal consumption.

Clean power covers electricity demand growth

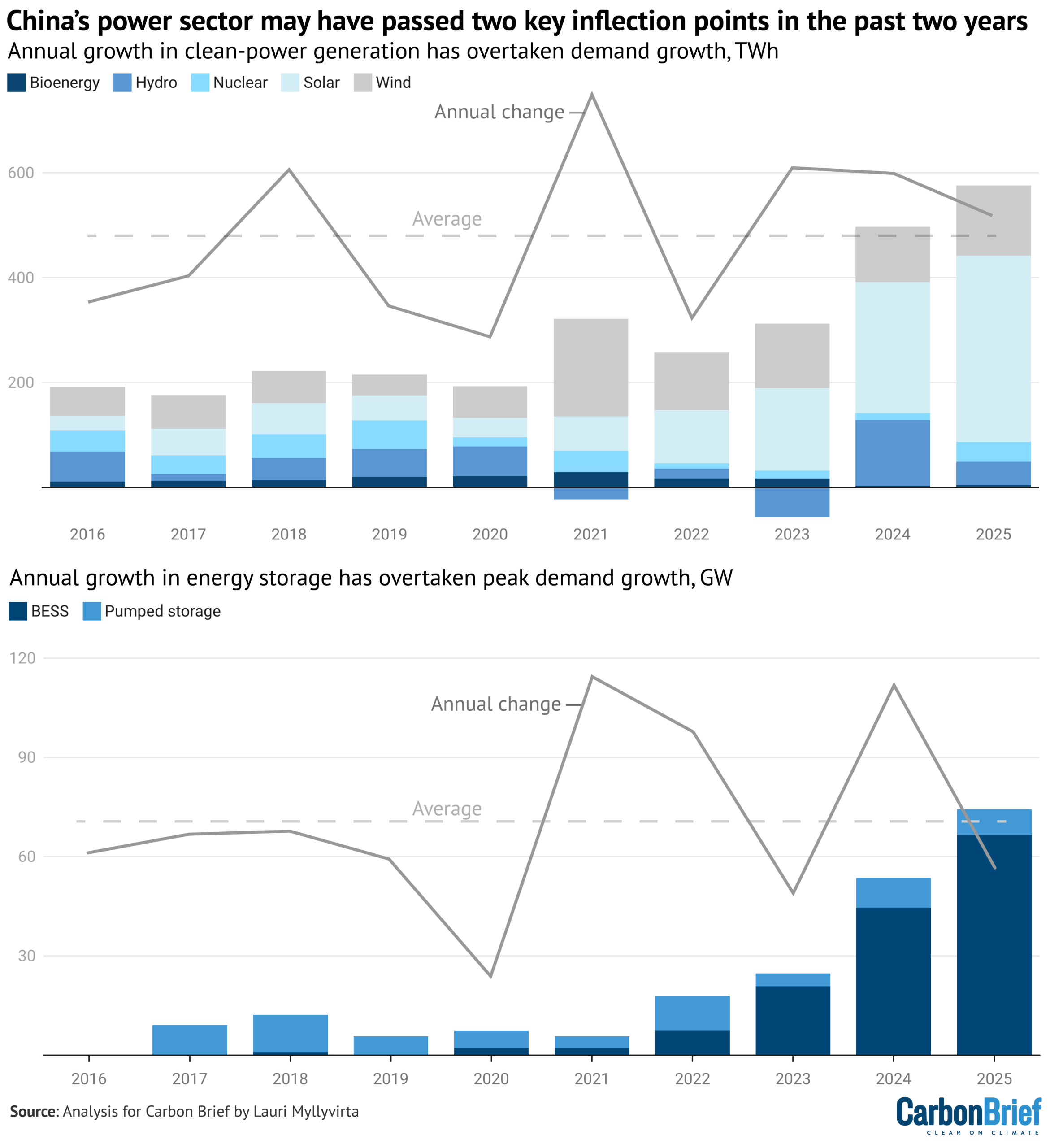

In the power sector, which is China’s largest emitter by far, electricity demand grew by 520 terawatt hours (TWh) in 2025.

At the same time, power generation from solar increased by 43% and wind power generation by 14%, delivering 360TWh and 130TWh of additional clean electricity. Nuclear power generation grew 8%, supplying another 40TWh. The increased generation from these three sources – some 530TWh – therefore met all of the growth in demand.

Hydropower generation also increased by 3% and bioenergy by 3%, helping push power generation from fossil fuels down by 1%. Gas-fired power generation increased by 6% and, as a result, power generation from coal fell by 1.9%.

Furthermore, the surge in additions of new wind and solar capacity at the end of 2025 will only show up as increased clean-power generation in 2026.

On the other hand, the growth in solar and wind power generation has fallen short of the growth in capacity, implying a fall in capacity utilisation – a measure of actual output relative to the maximum possible. This is highly likely due to increased, unreported curtailment, where wind and solar sites are switched off because the electricity grid is congested.

If these grid issues are resolved over the next few years, then generation from existing wind and solar capacity will increase over time.

Developments in 2025 extended the trend of clean-power generation growing faster than power demand overall, as shown in the top figure below. This trend started in 2023 and is the key reason why China’s emissions have been stable or falling since early 2024.

In addition, 2025 saw another potential inflection point, shown in the bottom figure below. It was the first year ever that energy storage capacity – mainly batteries – grew faster than peak electricity demand in 2025 and faster than the average growth in the past decade.

China’s energy storage capacity increased by 75GW year-on-year in 2025, while peak demand only increased by 55GW. The rise in storage capacity in 2025 is also larger than the three-year average increase in peak loads, some 72GW per year.

Peak demand growth matters, because power systems have to be designed to reliably provide enough electricity supply at the moment of highest demand.

Moreover, the increase in peak loads is a key driver of continued additions of coal and gas-fired power plants, which reached the highest level in a decade in 2025.

The growth in energy storage could provide China with an alternative way to meet peak loads without relying on increased fossil fuel-based capacity.

The growth in storage capacity is set to continue after a new policy issued by China’s top economic planner the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) in January.

This policy means energy storage sites will be supported by so-called “capacity payments”, which to date have only been available to coal- and gas-fired power plants and pumped hydro storage.

Concerns about having sufficient “firm” power capacity in the grid – that which can be turned on at will – led the government to promote new coal and gas-fired power projects in recent years, leading to the largest fossil-fuel based capacity additions in a decade in 2025, with another 290GW of coal-fired capacity still under construction.

Reforming the power system and increasing storage capacity would enable the grid to accommodate much higher shares of solar and wind, while reducing the need for new coal or gas capacity to meet rising peaks in demand.

This would both unlock more clean-power generation from existing capacity and improve the economics and risk profiles of new projects, stimulating more growth in capacity.

Peaking power CO2 requires more clean-energy growth

China’s key climate commitments for the next five-year period until 2030 are to peak CO2 emissions and to reduce carbon intensity by more than 65% from 2005 levels. The latter target requires limiting CO2 emissions at or below their 2025 level in 2030.

The record clean-energy additions in 2023-25 have barely sufficed to stabilise power-sector emissions, showing that if rapid growth in power demand continues, meeting the 2030 targets requires keeping clean-energy additions close to 2025 levels over the next five years.

China’s central government continues to telegraph a much lower level of ambition, with the NDRC setting a target of “around” 30% of power generation in 2030 coming from solar and wind, up from around 22% in 2025.

If electricity demand grows in line with the State Grid forecast of 5.6% per year, then limiting the share of wind and solar to 30% would leave space for fossil-fuel generation to grow at 3% per year from 2025 to 2030, even after increases from nuclear and hydropower.

Such an increase would mean missing China’s Paris commitments for 2030.

Alternatively, in order to meet the forecast increase in electricity demand without increasing generation from fossil fuels would require wind and solar’s share to reach 37% in 2030.

Similarly, China’s target of a non-fossil energy share of 25% in 2030 will not be sufficient to meet its carbon-intensity reduction commitment for 2030, unless energy demand growth slows down sharply.

This target is unlikely to be upgraded, since it is already enshrined in China’s Paris Agreement pledge, so in practice the target would need to be substantially overachieved if the country is to meet its other commitments.

If energy demand growth continues at the 2025 rate and the share of non-fossil energy only rises from 22% in 2025 to 25% in 2030, then the consumption of fossil fuels would increase by 3% per year, with a similar rise in CO2 emissions.

Still, another recent sign that clean-energy growth could keep exceeding government targets came in early February when the China Electricity Council projected solar and wind capacity additions of more than 300GW in 2026 – well beyond the government goal of “over 200GW”.

Chemical industry

The only significant source of growth in CO2 emissions in 2025 was the chemical industry, with sharp increases in the consumption of both coal and oil.

This is shown in the figure below, which illustrates how CO2 emissions appear to have peaked from cement production, transport, the power sector and others, whereas the chemicals industry is posting strong increases.

Even though chemical-industry emissions are small relative to other sectors – at roughly 13% of China’s total – the pace of expansion is creating an outsize impact.

Without the increase from the chemicals sector, China’s total CO2 emissions would have fallen by an estimated 2%, instead of the 0.3% reported here.

Without changes to policy, emission growth is set to continue, as the coal-to-chemicals industry is planning major increases in capacity.

Whether these expansion plans receive backing in the upcoming five-year plan for 2026-30 will have a major impact on China’s emission trends.

Another key factor is the development of oil and gas prices. Production in the coal-based chemical industry is only profitable when coal is significantly cheaper than crude oil.

The current coal-to-chemicals capacity in China is dominated by plants producing higher-value – and therefore less price-sensitive – chemicals such as olefins and aromatics, as feedstocks for the production of plastics.

In contrast, the planned expansion of the sector is expected to be largely driven by plants producing oil products and synthetic gas to be used for energy. For these products, electrification and clean-electricity generation provide a direct alternative, meaning they are even more sensitive to low oil and gas prices than chemicals production.

Outlook for China’s emissions

This is the latest analysis for Carbon Brief to show that China’s CO2 emissions have now been stable or falling for seven quarters or 21 months, marking the first such streak on record that has not been associated with a slowdown in energy demand growth.

Notably, while emissions have stabilised or begun a slow decline, there has not yet been a substantial reduction from the level reached in early 2024. This means that a small jump in emissions could see them exceed the previous peak level.

China’s official plans only call for peaking emissions shortly before 2030, which would allow for a rebound from the current plateau before the ultimate emissions peak.

If China is to meet its 2030 carbon intensity commitment – a 65% reduction on 2005 levels – then emissions would have to fall from the peak back to current levels by 2030.

Whether China’s policymakers are still committed to meeting this carbon intensity pledge, after the setbacks during the previous five-year period, is a key open question. The 2030 energy targets set to date have fallen short of what would be required.

The most important signal will be whether the top-level five-year plan for 2026-30, due in March, sets a carbon intensity target aligned with the 2030 Paris commitment.

Officially, China is sticking to the timeline of peaking CO2 emissions “before 2030”, which was announced by president Xi Jinping in 2020.

According to an authoritative explainer on the recommendations of the Central Committee of the Communist Party for the upcoming five-year plan, published by state-backed news agency Xinhua, coal consumption should “reach its peak and enter a plateau” from 2027.

It says that continued increases in demand for coal from electricity generators and the chemicals industry would be offset by reductions elsewhere. This is despite the fact that China’s coal consumption overall has already been falling for close to two years.

The reference to a “plateau” in coal consumption indicates that in official plans, meaningful absolute reductions in emissions would have to wait until after 2030. Any increase in coal consumption from 2025 to 2027, before the targeted plateau, would need to be offset by reductions in oil consumption, to meet the carbon intensity target.

Moreover, allowing coal consumption in the power sector to grow beyond the peak of overall coal use and emissions implies slowing down China’s clean-energy boom. So far, the boom has continued to exceed official targets by a wide margin.

In addition, the explainer’s expectation of further growth in coal use by the chemicals industry indicates a green light for at least a part of its sizable expansion plans.

The Xinhua article recognises that oil product consumption has already peaked, but says that oil use in the chemicals industry has kept growing. It adds that overall oil consumption should peak in 2026.

Elsewhere, the article speaks of “vigorously” developing non-fossil energy and “actively” developing “distributed” solar, which has slowed down due to recent pricing policies.

Yet it also calls for “high-quality development” of fossil fuels and increased efforts in domestic oil and gas production, suggesting that China continues to take an “all of the above” approach to energy policy.

The outcome of all this depends on how things turn out in reality. The past few years show it is possible that clean energy will continue to overperform its targets, preventing growth in energy consumption from fossil fuels despite this policy support.

The key role of the clean-energy boom in driving GDP growth and investments is one key motivator for policymakers to keep the boom going, even when central targets would allow for a slowdown. It is also possible that the five-year plans of provinces and state-owned enterprises could play a key role in raising ambition, as they did in 2022.

About the data

Data for the analysis was compiled from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, National Energy Administration of China, China Electricity Council and China Customs official data releases, as well as from industry data provider WIND Information and from Sinopec, China’s largest oil refiner.

Electricity generation from wind and solar, along with thermal power breakdown by fuel, was calculated by multiplying power generating capacity at the end of each month by monthly utilisation, using data reported by China Electricity Council through Wind Financial Terminal.

Total generation from thermal power and generation from hydropower and nuclear power were taken from National Bureau of Statistics monthly releases.

Monthly utilisation data was not available for biomass, so the annual average of 52% for 2023 was applied. Power-sector coal consumption was estimated based on power generation from coal and the average heat rate of coal-fired power plants during each month, to avoid the issue with official coal consumption numbers affecting recent data.

CO2 emissions estimates are based on National Bureau of Statistics default calorific values of fuels and emissions factors from China’s latest national greenhouse gas emissions inventory, for the year 2021. The CO2 emissions factor for cement is based on annual estimates up to 2024.

For oil, apparent consumption of transport fuels – diesel, petrol and jet fuel – is taken from Sinopec quarterly results, with monthly disaggregation based on production minus net exports. The consumption of these three fuels is labeled as oil product consumption in transportation, as it is the dominant sector for their use.

Apparent consumption of other oil products is calculated from refinery throughput, with the production of the transport fuels and the net exports of other oil products subtracted. Fossil-fuel consumption includes non-energy use such as plastics, as most products are short-lived and incineration is the dominant disposal method.

The post Analysis: China’s CO2 emissions have now been ‘flat or falling’ for 21 months appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: China’s CO2 emissions have now been ‘flat or falling’ for 21 months

Greenhouse Gases

Analysis: Half of nations meet UN deadline for nature-loss reporting

Half of nations have met a UN deadline to report on how they are tackling nature loss within their borders, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

This includes 11 of the 17 “megadiverse nations”, countries that account for 70% of Earth’s biodiversity.

It also includes all of the G7 nations apart from the US, which is not part of the world’s nature treaty.

All 196 countries that are part of the UN biodiversity treaty were due to submit their seventh “national reports” by 28 February, of which 98 have done so.

Their submissions are supposed to provide key information for an upcoming global report on actions to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030, in addition to a global review of progress due to be conducted by countries at the COP17 nature summit in Armenia in October this year.

At biodiversity talks in Rome in February, UN officials said that national reports submitted late will not be included in the global report due to a lack of time, but could still be considered in the global review.

Tracking nature action

In 2022, nations signed a landmark deal to halt and reverse nature loss by 2030, known as the “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework” (GBF).

In an effort to make sure countries take action at the domestic level, the GBF included an “implementation schedule”, involving the publishing of new national plans in 2024 and new national reports in 2026.

The two sets of documents were to inform both a global report and a global review, to be conducted by countries at COP17 in Armenia later this year. (This schedule mirrors the one set out for tackling climate change under the Paris Agreement.)

The deadline for nations’ seventh national reports, which contain information on their progress towards meeting the 23 targets of the GBF based on a set of key indicators, was 28 February 2026.

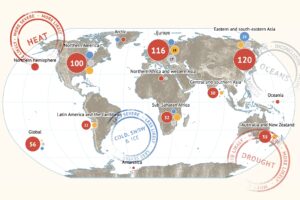

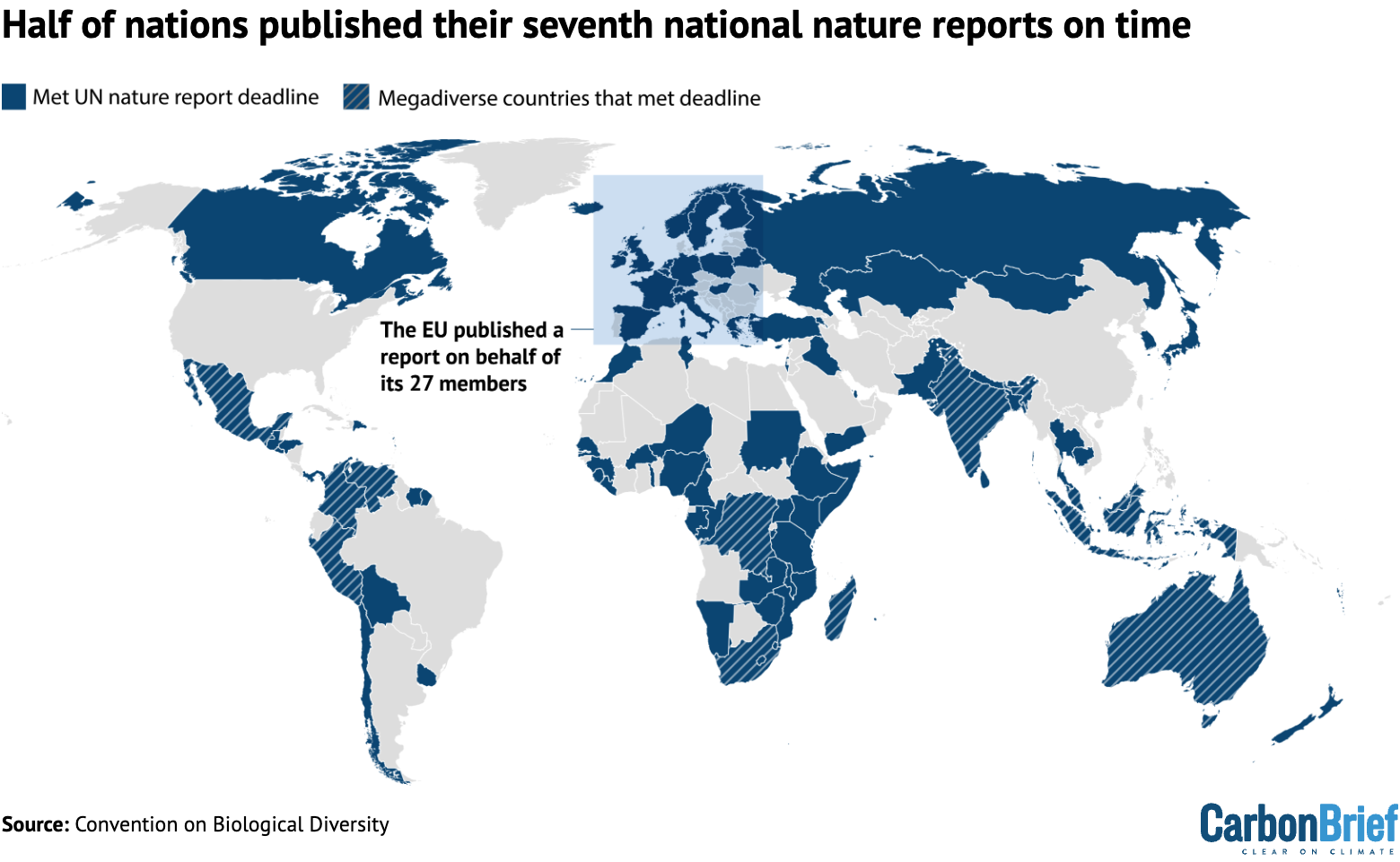

According to Carbon Brief’s analysis of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity’s online reporting platform, 98 out of the 196 countries that are part of the nature convention (50%) submitted on time.

The map below shows countries that submitted their seventh national reports by the UN’s deadline.

This includes 11 of the 17 “megadiverse nations” that account for 70% of Earth’s biodiversity.

The megadiverse nations to meet the deadline were India, Venezuela, Indonesia, Madagascar, Peru, Malaysia, South Africa, Colombia, Mexico, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Australia.

It also includes all of the G7 nations (France, Germany, the UK, Japan, Italy and Canada), excluding the US, which has never ratified the Convention on Biological Diversity.

The UK’s seventh national report shows that it is currently on track to meet just three of the GBF’s 23 targets.

This is according to a LinkedIn post from Dr David Cooper, former executive secretary of the CBD and current chair of the UK’s Joint Nature Conservation Committee, which coordinated the UK’s seventh national report,

The report shows the UK is not on track to meet one of the headline targets of the GBF, which is to protect 30% of land and sea for nature by 2030.

It reports that the proportion of land protected for nature is 7% in England, 18% in Scotland and 9% in Northern Ireland. (The figure is not given for Wales.)

National plans

In addition to the national reports, the upcoming global report and review will draw on countries’ national plans.

Countries were meant to have submitted their new national plans, known as “national biodiversity strategies and action plans” (NBSAPs), by the start of COP16 in October 2024.

A joint investigation by Carbon Brief and the Guardian found that only 15% of member countries met that deadline.

Since then, the percentage of countries that have submitted a new NBSAP has risen to 39%.

According to the GBF and its underlying documents, countries that were “not in a position” to meet the deadline to submit NBSAPs ahead of COP16 were requested to instead submit national targets. These submissions simply list biodiversity targets that countries will aim for, without an accompanying plan for how they will be achieved.

As of 2 March, 78% of nations had submitted national targets.

At biodiversity talks in Rome in February, UN officials said that national reports submitted late will not be included in the global report due to a lack of time, but could still be considered in the global review.

Funding ‘delays’

At the Rome talks, some countries raised that they had faced “difficulties in submitting [their national reports] on time”, according to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin.

Speaking on behalf of “many” countries, Fiji said that there had been “technical and financial constraints faced by parties” in the preparation of their seventh national reports.

In a statement to Carbon Brief, a spokesperson for the Global Environment Facility, the body in charge of providing financial and technical assistance to countries for the preparation of their national reports, said “delays in fund disbursement have occurred in some cases”, adding:

“In 2023, the GEF council approved support for the development of NBSAPs and the seventh national reports for all 139 eligible countries that requested assistance. This includes national grants of up to $450,000 per country and $6m in global technical assistance delivered through the UN Development Programme and UN Environment Programme.

“As of the end of January 2026, all 139 participating countries had benefited from technical assistance and 93% had accessed their national grants, with 11 countries yet to receive their funds. Delays in fund disbursement have occurred in some cases, compounded by procurement challenges and limited availability of technical expertise.”

The spokesperson added that the fund will “continue to engage closely with agencies and countries to support timely completion of NBSAPs and the seventh national reports”.

The post Analysis: Half of nations meet UN deadline for nature-loss reporting appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Half of nations meet UN deadline for nature-loss reporting

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Absolute State of the Union

‘DRILL, BABY’: US president Donald Trump “doubled down on his ‘drill, baby, drill’ agenda” in his State of the Union (SOTU) address, said the Los Angeles Times. He “tout[ed] his support of the fossil-fuel industry and renew[ed] his focus on electricity affordability”, reported the Financial Times. Trump also attacked the “green new scam”, noted Carbon Brief’s SOTU tracker.

COAL REPRIEVE: Earlier in the week, the Trump administration had watered down limits on mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants, reported the Financial Times. It remains “unclear” if this will be enough to prevent the decline of coal power, said Bloomberg, in the face of lower-cost gas and renewables. Reuters noted that US coal plants are “ageing”.

OIL STAY: The US Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments brought by the oil industry in a “major lawsuit”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper said the firms are attempting to head off dozens of other lawsuits at state level, relating to their role in global warming.

SHIP-SHILLING: The Trump administration is working to “kill” a global carbon levy on shipping “permanently”, reported Politico, after succeeding in delaying the measure late last year. The Guardian said US “bullying” could be “paying off”, after Panama signalled it was reversing its support for the levy in a proposal submitted to the UN shipping body.

Around the world

- RARE EARTHS: The governments of Brazil and India signed a deal on rare earths, said the Times of India, as well as agreeing to collaborate on renewable energy.

- HEAT ROLLBACK: German homes will be allowed to continue installing gas and oil heating, under watered-down government plans covered by Clean Energy Wire.

- BRAZIL FLOODS: At least 53 people died in floods in the state of Minas Gerais, after some areas saw 170mm of rain in a few hours, reported CNN Brasil.

- ITALY’S ATTACK: Italy is calling for the EU to “suspend” its emissions trading system (ETS) ahead of a review later this year, said Politico.

- COOKSTOVE CREDITS: The first-ever carbon credits under the Paris Agreement have been issued to a cookstove project in Myanmar, said Climate Home News.

- SAUDI SOLAR: Turkey has signed a “major” solar deal that will see Saudi firm ACWA building 2 gigawatts in the country, according to Agence France-Presse.

$467 billion

The profits made by five major oil firms since prices spiked following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine four years ago, according to a report by Global Witness covered by BusinessGreen.

Latest climate research

- Claims about the “fingerprint” of human-caused climate change, made in a recent US Department of Energy report, are “factually incorrect” | AGU Advances

- Large lakes in the Congo Basin are releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere from “immense ancient stores” | Nature Geoscience

- Shared Socioeconomic Pathways – scenarios used regularly in climate modelling – underrepresent “narratives explicitly centring on democratic principles such as participation, accountability and justice” | npj Climate Action

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

The constituency of Richard Tice MP, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of Reform UK, is the second-largest recipient of flood defence spending in England, according to new Carbon Brief analysis. Overall, the funding is disproportionately targeted at coastal and urban areas, many of which have Conservative or Liberal Democrat MPs.

Spotlight

Is there really a UK ‘greenlash’?

This week, after a historic Green Party byelection win, Carbon Brief looks at whether there really is a “greenlash” against climate policy in the UK.

Over the past year, the UK’s political consensus on climate change has been shattered.

Yet despite a sharp turn against climate action among right-wing politicians and right-leaning media outlets, UK public support for climate action remains strong.

Prof Federica Genovese, who studies climate politics at the University of Oxford, told Carbon Brief:

“The current ‘war’ on green policy is mostly driven by media and political elites, not by the public.”

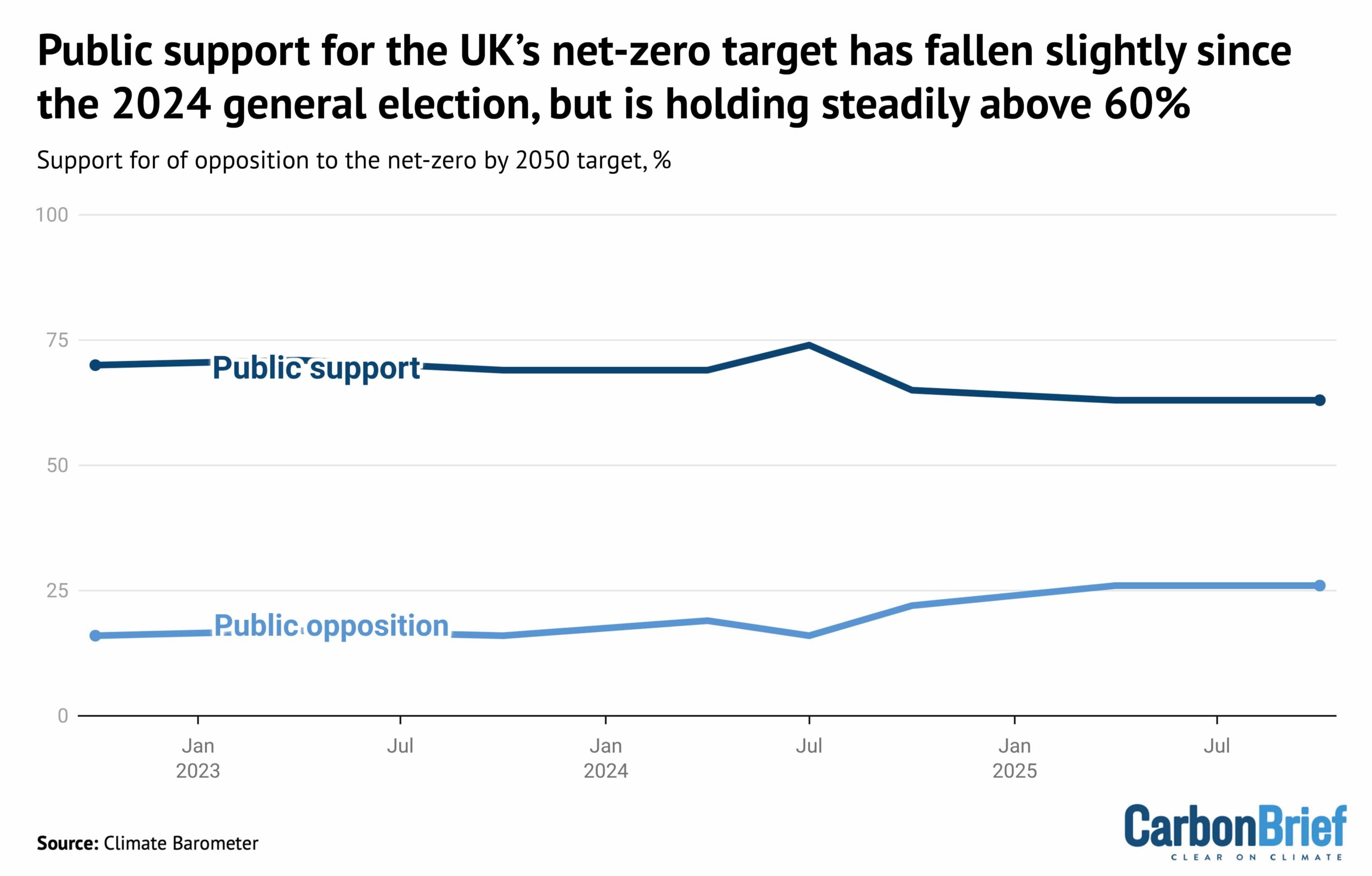

Indeed, there is still a greater than two-to-one majority among the UK public in favour of the country’s legally binding target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, as shown below.

Steve Akehurst, director of public-opinion research initiative Persuasion UK, also noted the growing divide between the public and “elites”. He told Carbon Brief:

“The biggest movement is, without doubt, in media and elite opinion. There is a bit more polarisation and opposition [to climate action] among voters, but it’s typically no more than 20-25% and mostly confined within core Reform voters.”

Conservative gear shift

For decades, the UK had enjoyed strong, cross-party political support for climate action.

Lord Deben, the Conservative peer and former chair of the Climate Change Committee, told Carbon Brief that the UK’s landmark 2008 Climate Change Act had been born of this cross-party consensus, saying “all parties supported it”.

Since their landslide loss at the 2024 election, however, the Conservatives have turned against the UK’s target of net-zero emissions by 2050, which they legislated for in 2019.

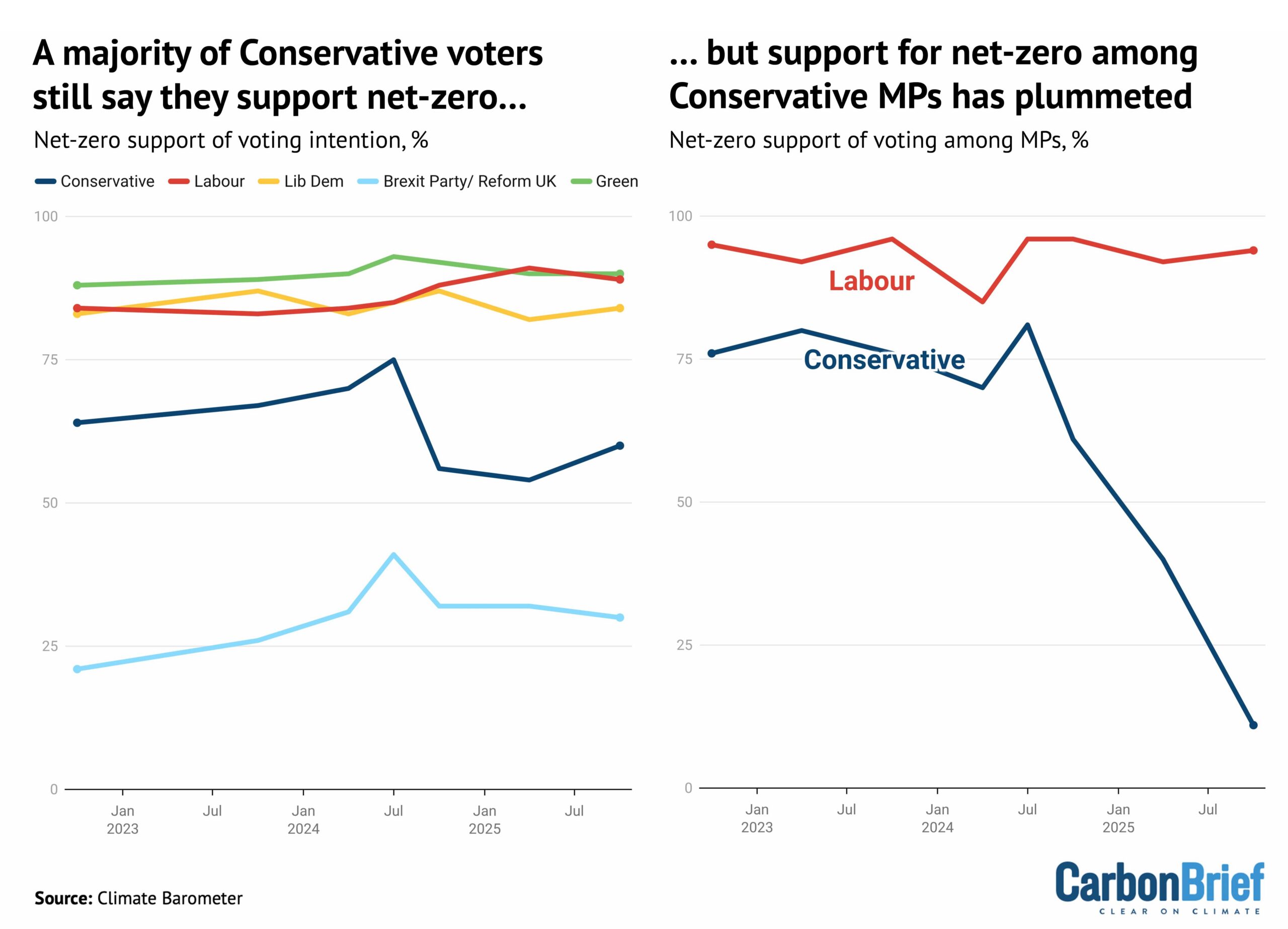

Curiously, while opposition to net-zero has surged among Conservative MPs, there is majority support for the target among those that plan to vote for the party, as shown below.

Dr Adam Corner, advisor to the Climate Barometer initiative that tracks public opinion on climate change, told Carbon Brief that those who currently plan to vote Reform are the only segment who “tend to be more opposed to net-zero goals”. He said:

“Despite the rise in hostile media coverage and the collapse of the political consensus, we find that public support for the net-zero by 2050 target is plateauing – not plummeting.”

Reform, which rejects the scientific evidence on global warming and campaigns against net-zero, has been leading the polls for a year. (However, it was comfortably beaten by the Greens in yesterday’s Gorton and Denton byelection.)

Corner acknowledged that “some of the anti-net zero noise…[is] showing up in our data”, adding:

“We see rising concerns about the near-term costs of policies and an uptick in people [falsely] attributing high energy bills to climate initiatives.”

But Akehurst said that, rather than a big fall in public support, there had been a drop in the “salience” of climate action:

“So many other issues [are] competing for their attention.”

UK newspapers published more editorials opposing climate action than supporting it for the first time on record in 2025, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Global ‘greenlash’?

All of this sits against a challenging global backdrop, in which US president Donald Trump has been repeating climate-sceptic talking points and rolling back related policy.

At the same time, prominent figures have been calling for a change in climate strategy, sold variously as a “reset”, a “pivot”, as “realism”, or as “pragmatism”.

Genovese said that “far-right leaders have succeeded in the past 10 years in capturing net-zero as a poster child of things they are ‘fighting against’”.

She added that “much of this is fodder for conservative media and this whole ecosystem is essentially driving what we call the ‘greenlash’”.

Corner said the “disconnect” between elite views and the wider public “can create problems” – for example, “MPs consistently underestimate support for renewables”. He added:

“There is clearly a risk that the public starts to disengage too, if not enough positive voices are countering the negative ones.”

Watch, read, listen

TRUMP’S ‘PETROSTATE’: The US is becoming a “petrostate” that will be “sicker and poorer”, wrote Financial Times associate editor Rana Forohaar.

RHETORIC VS REALITY: Despite a “political mood [that] has darkened”, there is “more green stuff being installed than ever”, said New York Times columnist David Wallace-Wells.

CHINA’S ‘REVOLUTION’: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast reported from China on the “green energy revolution” taking place in the country.

Coming up

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean, Brasília

- 3 March: UK spring statement

- 4-11 March: China’s “two sessions”

- 5 March: Nepal elections

Pick of the jobs

- The Guardian, senior reporter, climate justice | Salary: $123,000-$135,000. Location: New York or Washington DC

- China-Global South Project, non-resident fellow, climate change | Salary: Up to $1,000 a month. Location: Remote

- University of East Anglia, PhD in mobilising community-based climate action through co-designed sports and wellbeing interventions | Salary: Stipend (unknown amount). Location: Norwich, UK

- TABLE and the University of São Paulo, Brazil, postdoctoral researcher in food system narratives | Salary: Unknown. Location: Pirassununga, Brazil

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding

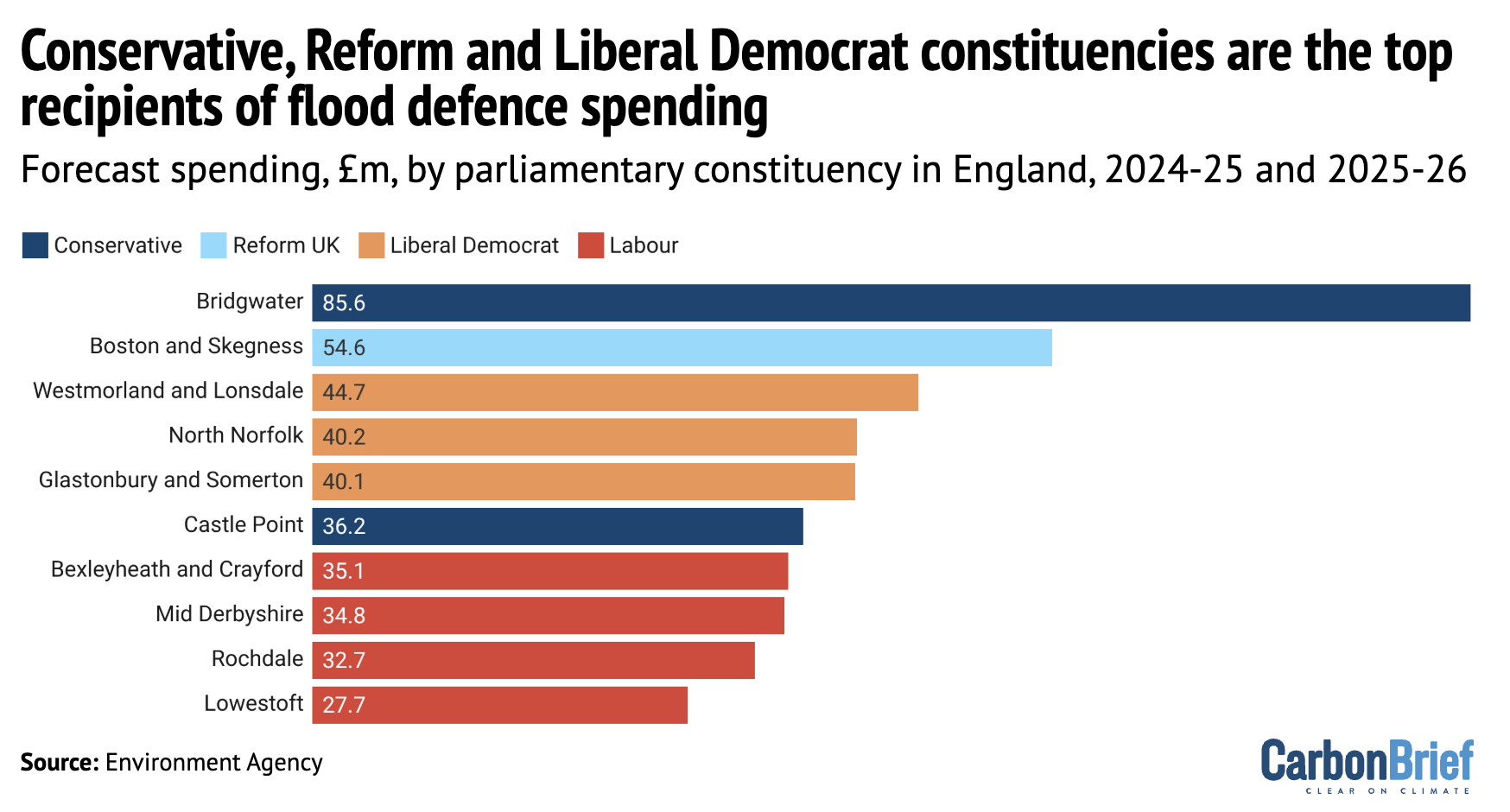

The Lincolnshire constituency held by Richard Tice, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of the hard-right Reform party, has been pledged at least £55m in government funding for flood defences since 2024.

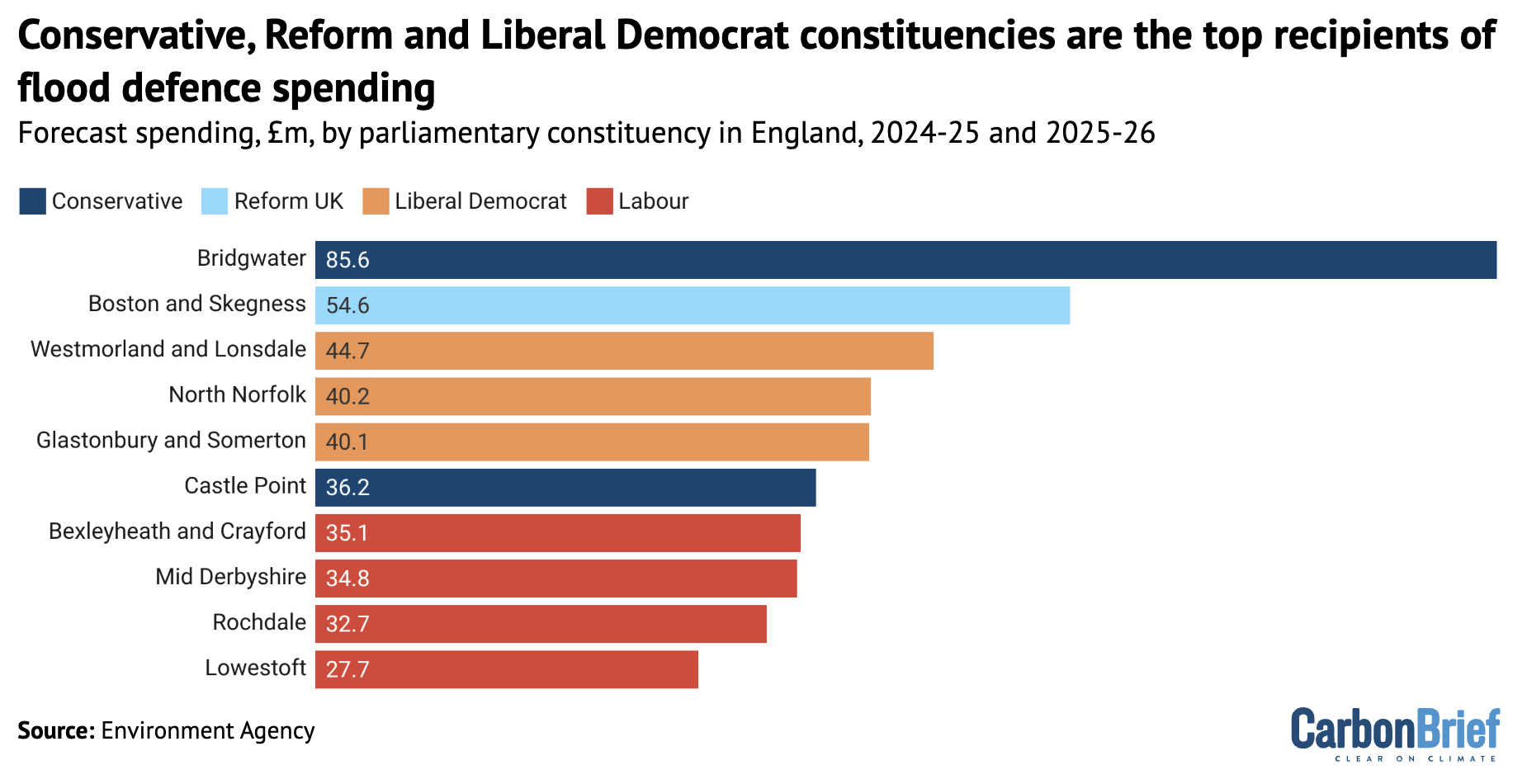

This investment in Boston and Skegness is the second-largest sum for a single constituency from a £1.4bn flood-defence fund for England, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

Flooding is becoming more likely and more extreme in the UK due to climate change.

Yet, for years, governments have failed to spend enough on flood defences to protect people, properties and infrastructure.

The £1.4bn fund is part of the current Labour government’s wider pledge to invest a “record” £7.9bn over a decade on protecting hundreds of thousands of homes and businesses from flooding.

As MP for one of England’s most flood-prone regions, Tice has called for more investment in flood defences, stating that “we cannot afford to ‘surrender the fens’ to the sea”.

He is also one of Reform’s most vocal opponents of climate action and what he calls “net stupid zero”. He denies the scientific consensus on climate change and has claimed, falsely and without evidence, that scientists are “lying”.

Flood defences

Last year, the government said it would invest £2.65bn on flood and coastal erosion risk management (FCERM) schemes in England between April 2024 and March 2026.

This money was intended to protect 66,500 properties from flooding. It is part of a decade-long Labour government plan to spend more than £7.9bn on flood defences.

There has been a consistent shortfall in maintaining England’s flood defences, with the Environment Agency expecting to protect fewer properties by 2027 than it had initially planned.

The Climate Change Committee (CCC) has attributed this to rising costs, backlogs from previous governments and a lack of capacity. It also points to the strain from “more frequent and severe” weather events, such as storms in recent years that have been amplified by climate change.

However, the CCC also said last year that, if the 2024-26 spending programme is delivered, it would be “slightly closer to the track” of the Environment Agency targets out to 2027.

The government has released constituency-level data on which schemes in England it plans to fund, covering £1.4bn of the 2024-26 investment. The other half of the FCERM spending covers additional measures, from repairing existing defences to advising local authorities.

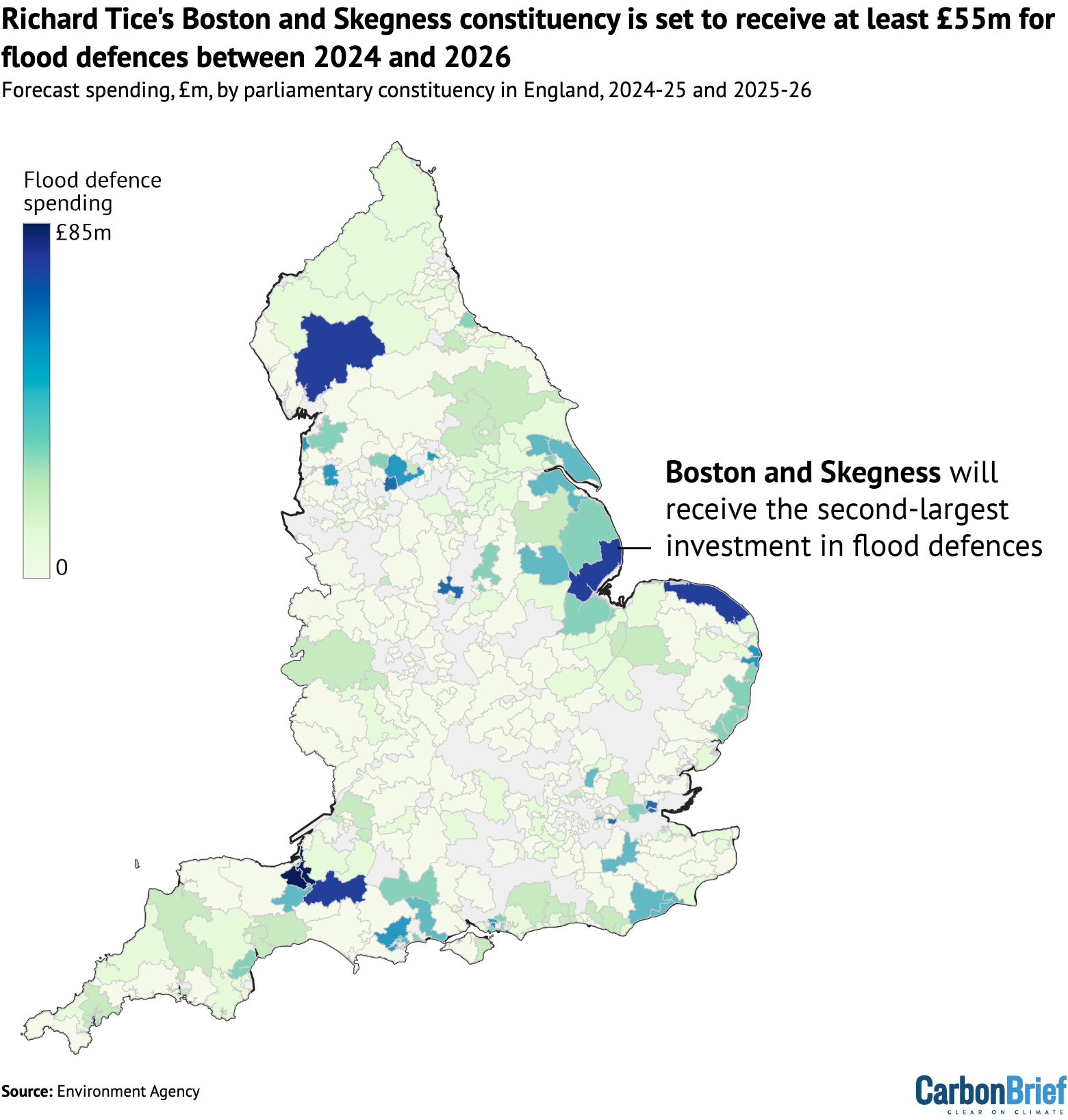

The map below shows the distribution of spending on FCERM schemes in England over the past two years, highlighting the constituency of Richard Tice.

By far the largest sum of money – £85.6m in total – has been committed to a tidal barrier and various other defences in the Somerset constituency of Bridgwater, the seat of Conservative MP Ashley Fox.

Over the first months of 2026, the south-west region has faced significant flooding and Fox has called for more support from the government, citing “climate patterns shifting and rainfall intensifying”.

He has also backed his party’s position that “the 2050 net-zero target is impossible” and called for more fossil-fuel extraction in the North Sea.

Tice’s east-coast constituency of Boston and Skegness, which is highly vulnerable to flooding from both rivers and the sea, is set to receive £55m. Among the supported projects are beach defences from Saltfleet to Gibraltar Point and upgrades to pumping stations.

Overall, Boston and Skegness has the second-largest portion of flood-defence funding, as the chart below shows. Constituencies with Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs occupied the other top positions.

Overall, despite Labour MPs occupying 347 out of England’s 543 constituencies – nearly two-thirds of the total – more than half of the flood-defence funding was distributed to constituencies with non-Labour MPs. This reflects the flood risk in coastal and rural areas that are not traditional Labour strongholds.

Reform funding

While Reform has just eight MPs, representing 1% of the population, its constituencies have been assigned 4% of the flood-defence funding for England.

Nearly all of this money was for Tice’s constituency, although party leader Nigel Farage’s coastal Clacton seat in Kent received £2m.

Reform UK is committed to “scrapping net-zero” and its leadership has expressed firmly climate-sceptic views.

Much has been made of the disconnect between the party’s climate policies and the threat climate change poses to its voters. Various analyses have shown the flood risk in Reform-dominated areas, particularly Lincolnshire.

Tice has rejected climate science, advocated for fossil-fuel production and criticised Environment Agency flood-defence activities. Yet, he has also called for more investment in flood defences, stating that “we cannot afford to ‘surrender the fens’ to the sea”.

This may reflect Tice’s broader approach to climate change. In a 2024 interview with LBC, he said:

“Where you’ve got concerns about sea level defences and sea level rise, guess what? A bit of steel, a bit of cement, some aggregate…and you build some concrete sea level defences. That’s how you deal with rising sea levels.”

While climate adaptation is viewed as vital in a warming world, there are limits on how much societies can adapt and adaptation costs will continue to increase as emissions rise.

The post Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits