Sustainable Aviation Fuel

Understanding Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ) Technology

Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ) technology involves the conversion of alcohols, such as ethanol or butanol, into aviation fuel through a series of catalytic processes.

The alcohol feedstocks can be sourced from various renewable sources, including biomass, agricultural waste, or even carbon dioxide captured from industrial emissions. The resulting ATJ fuels possess similar characteristics to conventional jet fuels, making them compatible with existing aircraft and infrastructure.

As the aviation industry seeks to reduce its environmental impact and mitigate climate change, Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ) technology has emerged as a promising solution. ATJ fuels are sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) derived from alcohol feedstocks, offering a viable alternative to traditional petroleum-based jet fuels.

This article explores the concept of ATJ technology, its environmental benefits, and its potential to transform the aviation sector towards a greener future.

Definition of Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ)

Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ) is a term used to describe a process that converts alcohol-based feedstocks into aviation jet fuel. It involves the production of sustainable, renewable jet fuel from alcohols derived from various sources such as biomass, waste materials, or industrial byproducts.

The ATJ process typically begins with the production of alcohols such as ethanol or butanol through fermentation or other biochemical processes. These alcohols are then subjected to a series of chemical reactions, such as dehydration and oligomerization, to convert them into hydrocarbons resembling traditional jet fuel.

The resulting ATJ fuel has similar properties to conventional petroleum-based jet fuel, meeting the required specifications and performance standards for use in commercial and military aviation. It can be blended with fossil-based jet fuel or used as a drop-in replacement without the need for engine modifications or changes to existing infrastructure.

The development of Alcohol-to-Jet technology is aimed at reducing the carbon footprint of the aviation industry by providing a renewable alternative to fossil fuels. By utilizing sustainable feedstocks and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, ATJ fuels contribute to the overall efforts to mitigate climate change and promote environmental sustainability in aviation.

Benefit of Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ)

Environmental Benefits:

ATJ fuels offer significant environmental advantages over conventional jet fuels. The production of ATJ fuels results in significantly lower lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions, contributing to a reduction in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and addressing the aviation industry’s carbon footprint. By utilizing renewable feedstocks, ATJ technology enables the creation of a closed carbon cycle, where carbon emissions from aircraft are offset by the absorption of carbon dioxide during feedstock growth, thereby reducing net CO2 emissions.

Compatibility and Performance:

One of the key strengths of ATJ technology is its compatibility with existing aircraft and infrastructure. ATJ fuels can be seamlessly integrated into the existing aviation fuel supply chain without requiring modifications to aircraft engines or fueling infrastructure. Moreover, ATJ fuels have similar energy density and combustion characteristics to conventional jet fuels, ensuring comparable performance in terms of flight range, engine efficiency, and safety.

Energy Security and Resilience:

ATJ technology offers improved energy security and resilience for the aviation sector. By diversifying the fuel mix and reducing dependence on fossil fuels, ATJ fuels help mitigate the risks associated with price volatility and supply disruptions. Furthermore, the production of ATJ fuels from domestic and renewable sources reduces reliance on imported petroleum, strengthening the energy independence of countries and enhancing their overall energy security.

Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ) Production

Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ) production involves several steps to convert alcohol feedstocks into jet fuel.

Here’s a simplified overview of the process:

Feedstock selection: The first step is to choose a suitable alcohol feedstock, such as ethanol or butanol. These alcohols can be derived from various sources, including biomass (e.g., sugarcane, corn), waste materials (e.g., agricultural residues), or industrial byproducts.

Dehydration: The selected alcohol feedstock is subjected to a dehydration process to remove water content and produce a more concentrated alcohol. Dehydration can be achieved through various methods, including distillation, membrane separation, or molecular sieves.

Oligomerization: The dehydrated alcohol undergoes oligomerization, a chemical reaction that converts the alcohol molecules into larger hydrocarbon chains. This step typically involves the use of catalysts and heat to promote the formation of longer hydrocarbon compounds.

Hydroprocessing: The oligomerized alcohol is then subjected to hydroprocessing, which involves the introduction of hydrogen and the use of catalysts to further refine the hydrocarbon chains. This step helps improve the fuel’s properties, such as its energy density, volatility, and stability.

Fuel blending: The resulting ATJ fuel is often blended with conventional petroleum-based jet fuel to meet the required specifications and performance standards. Blending allows for a gradual transition and compatibility with existing aviation infrastructure and engines. The blend ratio can vary depending on the desired fuel characteristics and regulatory requirements.

Testing and certification: Before ATJ fuel can be used in commercial or military aviation, it must undergo rigorous testing and certification to ensure it meets the necessary quality and safety standards. These tests evaluate parameters such as combustion performance, emissions, freeze point, flash point, and material compatibility.

It’s important to note that the specific details of the ATJ production process may vary depending on the technology and company involved. Different approaches and proprietary methods exist, but the general concept revolves around converting alcohol feedstocks into a suitable jet fuel substitute through a series of chemical reactions and refining steps.

Challenges and Future Outlook:of Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ)

Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ) technology faces several challenges and opportunities in terms of its implementation and future outlook.

Here are some key considerations:

Feedstock availability: One of the main challenges is ensuring a reliable and sustainable supply of feedstocks for ATJ production. The availability, cost, and scalability of feedstock sources, such as biomass or waste materials, can impact the viability and economic feasibility of ATJ production on a large scale.

Technological advancements: Continued research and development efforts are necessary to improve the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the ATJ production process. This includes exploring innovative catalysts, refining techniques, and process optimization to enhance the overall conversion efficiency and yield of high-quality jet fuel.

Regulatory framework: The adoption and commercialization of ATJ fuels depend on supportive policy frameworks and regulations. Governments and regulatory bodies play a crucial role in incentivizing the use of sustainable aviation fuels, including ATJ, through mandates, tax incentives, and emissions reduction targets. Clear and stable policies can provide a favorable market environment for ATJ production and deployment.

Scale-up and infrastructure: Scaling up ATJ production to meet the demand of the aviation industry requires significant investment in infrastructure and production facilities. Building or retrofitting refineries, transportation and distribution networks, and storage facilities for ATJ fuels present logistical and financial challenges that need to be addressed.

Cost competitiveness: ATJ fuels currently face cost competitiveness challenges compared to conventional petroleum-based jet fuels. However, as technology advances, economies of scale are achieved, and production processes become more efficient, the cost gap is expected to narrow. Ongoing research and development efforts, as well as increased production volumes, are essential for cost reduction and improved market competitiveness.

Environmental sustainability: ATJ fuels offer the potential to significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and contribute to the decarbonization of the aviation sector. However, ensuring the environmental sustainability of ATJ production requires considering factors such as the lifecycle carbon footprint of feedstocks, land use impacts, water usage, and minimizing the use of non-renewable resources in the production process.

The future outlook for Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ) technology is promising. As the aviation industry strives to reduce its carbon footprint and meet sustainability goals, there is growing interest and support for the development and deployment of sustainable aviation fuels, including ATJ. Continued advancements in technology, supportive policies, and collaboration between industry, government, and research institutions can help overcome the challenges and accelerate the adoption of ATJ fuels as a viable and environmentally friendly alternative to conventional jet fuels.

While ATJ technology holds great promise, several challenges need to be addressed to facilitate its widespread adoption. These challenges include ensuring a sustainable and scalable supply of alcohol feedstocks, developing cost-effective conversion processes, and establishing regulatory frameworks and incentives to support the commercialization of ATJ fuels. Continued research and development efforts, along with collaboration between industry stakeholders and policymakers, are crucial to overcoming these challenges and unlocking the full potential of ATJ technology.

Conclusion for Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ) Production

Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ) production is a promising technology that enables the conversion of alcohol-based feedstocks into sustainable jet fuel.

It offers the potential to reduce the carbon footprint of the aviation industry and contribute to environmental sustainability. However, several challenges need to be addressed for widespread adoption.

The availability of reliable and sustainable feedstocks, technological advancements, supportive regulatory frameworks, and cost competitiveness are critical factors that will shape the future of ATJ production. Additionally, scaling up production, building necessary infrastructure, and ensuring environmental sustainability throughout the production process are key considerations.

Despite these challenges, the future outlook for ATJ production is optimistic. The aviation industry’s increasing focus on sustainability, coupled with research and development efforts, policy support, and collaboration between stakeholders, is driving the advancement and commercialization of ATJ fuels. As the technology matures, costs decrease, and production scales up, ATJ has the potential to play a significant role in reducing greenhouse gas emissions from aviation and promoting a more sustainable and low-carbon future.

Alcohol-to-Jet (ATJ) technology represents a significant step towards achieving sustainable aviation and reducing the environmental impact of the aviation sector. With its environmental benefits, compatibility with existing infrastructure, and potential to enhance energy security, ATJ fuels offer a viable pathway to decarbonize aviation and meet ambitious climate targets. By fostering innovation, promoting supportive policies, and encouraging industry collaboration, ATJ technology can play a pivotal role in transitioning the aviation industry to a greener and more sustainable future.

https://www.exaputra.com/2023/05/alcohol-to-jet-atj-production.html

Renewable Energy

Remembering G.W. Bush

In 2001, I remembered being deeply disappointed that G.W. Bush had become our 43rd U.S president, on the basis that he was clearly unintelligent, and that the Republicans were already climate deniers.

In 2001, I remembered being deeply disappointed that G.W. Bush had become our 43rd U.S president, on the basis that he was clearly unintelligent, and that the Republicans were already climate deniers.

That said, Bush was not criminally insane, and about half of all American voters would not support a psychotic in the White House.

Now, the vast majority of U.S. voters would be thrilled to trade out Donald Trump for the good old days of being led by a sane imbecile.

Renewable Energy

Understanding (or Failing to) Climate Denialism

I can’t understand how a young history/poli-sci major who has become a social media “influencer” has superior credibility to tens of thousands of climate scientists, many of whom I know personally, who have been studying this subject since the 1970s.

I can’t understand how a young history/poli-sci major who has become a social media “influencer” has superior credibility to tens of thousands of climate scientists, many of whom I know personally, who have been studying this subject since the 1970s.

Can someone help me here?

Renewable Energy

Sorry, Trump Couldn’t Care Less about Anyone but Himself

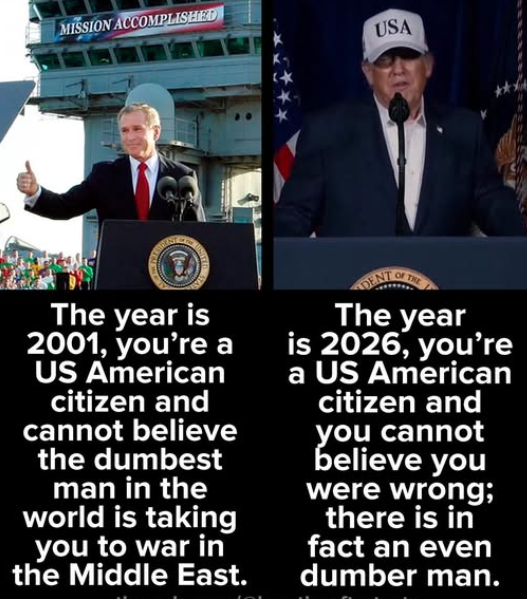

At first, I thought the meme at left was a joke, but upon further reflection, I realized that it was not.

At first, I thought the meme at left was a joke, but upon further reflection, I realized that it was not.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

.jpg)