Weather Guard Lightning Tech

Revolutionizing Wind Turbine Blade Inspections: Romotioncam Does it With No Downtime

Romotioncam is redefining the way operators inspect wind turbine blades—while the blades keep spinning.

In a recent Spotlight podcast , René Harendt, CTO of Romotioncam, and Dr. Michael Stamm, a researcher at Germany’s Federal Institute for Materials Research and Testing (BAM), spoke with Weatherguard Lightning Tech CEO Allen Hall and CCO Joel Saxum about the company’s unique inspection system.

By combining cutting-edge photographic technology, thermal diagnostics, and structural analysis, Romotioncam’s inspection system delivers accurate, in-depth, actionable data, while eliminating the need to shut down turbines.

How does it work? Read on.

The full interview – which includes a little more physics and some discussions about a blade’s unique thermal signature – was recorded in December, 2024. It can be found here.

A New Lens on Blade Inspections

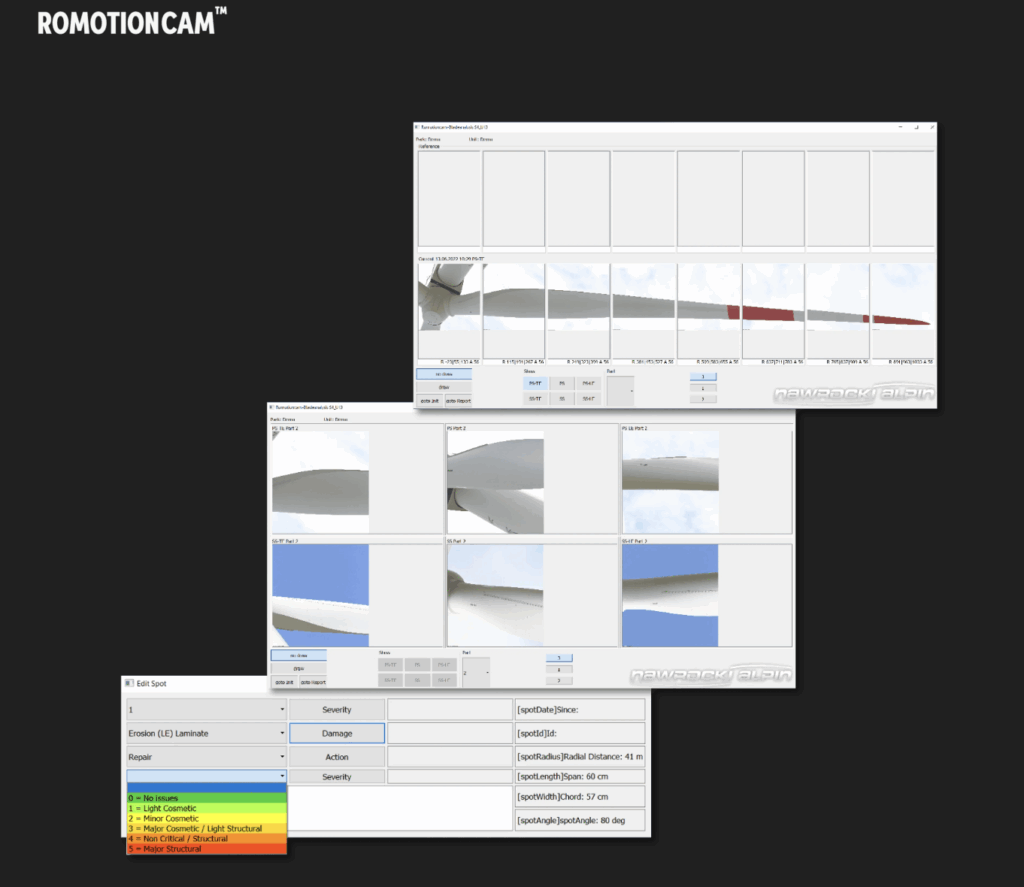

With a single camera mounted on a pan-tilt head, Romotioncam’s patented tracking system follows wind turbine blades as they rotate, even at high tip speeds. The system tracks the rotor and blade tips in real-time, capturing detailed images that allow inspectors to spot early-stage defects such as cracks, erosion, and structural deformations.

“Our camera system calculates the blade position and rotor speed and adjusts accordingly,” Harendt explained. “Even at high speeds, we can follow the tip, delivering stable, high-resolution imagery, without stopping the turbine.”

The patented process solves long-standing challenges of motion blur and incomplete data during traditional inspections that require turbines to be shut down.

“The information from this is remarkable,” Hall said.

Seeing Beneath the Surface: Thermal Imaging in Action

Research from BAM’s Dr. Stamm has added another dimension to the innovation: the thermal imaging of turbines while in operation—a practice historically limited by technology constraints.

“We needed synchronized, high-resolution visual imagery to make accurate interpretations of our thermal data,” Stamm said. “That’s where Romotioncam was the perfect match.”

By integrating both thermal and visual data into a single system, Romotioncam can detect aerodynamic inefficiencies and internal blade defects that were previously undetectable without physical access.

“Thermal signatures can tell us about laminar versus turbulent airflow, which in turn highlights surface erosion or leading-edge damage,” Stamm explained. “We can also detect structural anomalies—like delamination—due to variations in heat capacity across different blade materials.”

Need a refresher? Laminar vs. Turbulent Airflow, and Why It Matters

No Downtime Turbine Blade Inspections

For operators, Romotioncam’s biggest advantage may be that inspections can be done without lockout/tagout, and without field crews.

“You give us the location and specs. We capture the data remotely, independently, and you get a full report. You might not even know we were there,” Harendt said.

This remote, approach is a game-changer—especially during winter, when turbine downtime comes at a particularly high cost.

And while “no downtime” blade inspections has an undeniable appeal, the data is uniquely actionable.

“It helps operators assess not only structural safety, but also performance efficiency, which informs decisions on repair timing and can improve operational ROI,” Harendt noted.

From Research to Real-World Impact

The partnership between Romotioncam and BAM has already generated compelling data. Stamm reports that about 30 turbines have been analyzed using thermal imaging, with results publicly available. (link below) Stamm said the images clearly show how minor defects lead to turbulent airflow and energy losses.

“The visual overlay of turbulence and structural damage is remarkable,” Stamm. “We’re starting to see patterns that weren’t clear before. Sometimes, we find turbulence without visible damage, which raises new research questions.”

As wind farms globally find downtime becoming more expensive, Romotioncam’s fast, remote, intelligent inspections have tremendous appeal, providing high-quality, actionable data without equipment downtime.

What’s Next: Dual-Camera Systems, Deeper Insights – and a US project?

Romotioncam’s next milestone will be to integrate both thermal and visual cameras into a single, compact inspection unit to allow one-shot diagnostics with layered image analysis, providing a fuller picture of both external and internal blade health—potentially up to 10 cm deep.

“It’s not just about seeing damage,” Harendt said. “It’s about confirming that if you don’t see anything, there’s truly nothing there. And that requires understanding the right conditions for inspection.”

While Romotioncam is headquartered in Germany, and works primarily on European wind projects, Harendt said the company continues to look at expanding into the US.

Listen to the full interview here: Romotioncam: Inspections in Motion

See the Romotioncam system at work here

To learn more about the company and its services, call +49-30-443181-75, visit romotioncam.com, or email office@romotioncam.com

To see BAM’s research data and thermal imaging analysis, visit KI-Visir Project or Thermal Imaging Dataset on the BAM website.

https://weatherguardwind.com/revolutionizing-wind-turbine-blade-inspections-romotioncam-does-it-with-no-downtime/

Renewable Energy

Homeschooling

Decent and intelligent people respect the rights of parents to homeschool their children, but there are two reasons for concern: a) socialization, failure to expose children to their peers, so that they may make friends and come to understand the norms of society, and b) the quality of the education itself.

Almost all homeschooling in the United States is conducted on the basis of a radical rightwing viewpoint, normally a blend of evangelical Christianity and Trumpism.

Renewable Energy

The Positive Effects We’ve Had on Others Are Profound, Whether We Know It or Not

There’s a theory that most people underestimate the positive effects they’ve had on other people.

There’s a theory that most people underestimate the positive effects they’ve had on other people.

Yes, that’s the theme of “It’s a Wonderful Life,” but it’s also the core of the 1995 film “Mr. Holland’s Opus,” in which a music teacher who deemed that his life had been a failure because he never completed writing a great symphony, is gently and beautifully corrected. Please see below.

The Positive Effects We’ve Had on Others Are Profound, Whether We Know It or Not

Renewable Energy

Renewable Energy Concepts Can’t Violate the Laws of Physics

In the early days of 2GreenEnergy, my people and I were vigorously engaged in finding solid ideas in cleantech that needed funding in order to move forward.

In the early days of 2GreenEnergy, my people and I were vigorously engaged in finding solid ideas in cleantech that needed funding in order to move forward.

I vividly remember a conversation with a guy in Maryland who was trying to explain the (ostensible) breakthrough that he and his team had made in hydrokinetics. When I was having trouble visualizing what we was talking about, he asked me to “think of it as a river in a box.”

“Oh!” I exclaimed. “You mean you take a box full of standing water, add energy to it get it moving, then extract that energy, leaving you with more energy that you added to it.”

“Exactly.”

I politely explained that the laws of physics, specifically the first and second laws of thermodynamics, make this impossible.

He wasn’t through, however, and insisted that, in his office, his people had constructed a “working model.”

Here’s where my tone descended into something less than 100% polite. I told him that he may think he has a working model, but he’s wrong; if he believes this, he’s ignorant; if he doesn’t, but is conducting this conversation anyway, he’s a fraud.

“But don’t you want to come see it?” he implored.

“No. Not only would not fly across the country to see whatever it is you claim to have built, I wouldn’t walk across the street to a “working model” of something that is theoretically impossible.”

—

I tell this story because the claim made at the upper left is essentially identical. You’re pumping water up out of a stream, and then claiming to extract more energy when the water flows back into the stream.

Of course, social media today is rife with complete crap like this. We’ve devolved to a point where defrauding money out of idiots is rapidly replacing baseball as our national pastime.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits