Every year, understanding of climate science grows stronger.

With each new research project and published paper, scientists learn more about how the Earth system responds to continuing greenhouse gas emissions.

But with many thousands of new studies on climate change being published every year, it can be hard to keep up with the latest developments.

Our annual “10 new insights in climate science” report offers a snapshot of key advances in the scientific understanding of the climate system.

Produced by a team of scientists from around the world, the report summarises influential, novel and policy-relevant climate research published over the previous 18 months.

The insights presented in the latest edition, published in the journal Global Sustainability, are as follows:

- Questions remain about the record warmth in 2023-24

- Unprecedented ocean surface warming and intensifying marine heatwaves are driving severe ecological losses

- The global land carbon sink is under strain

- Climate change and biodiversity loss amplify each other

- Climate change is accelerating groundwater depletion

- Climate change is driving an increase in dengue fever

- Climate change diminishes labour productivity

- Safe scale-up of carbon dioxide removal is needed

- Carbon credit markets come with serious integrity challenges

- Policy mixes outperform stand-alone measures in advancing emissions reductions

In this article, we unpack some of the key findings.

A strained climate system

The first three insights highlight how strains are growing across the climate system, from indications of an accelerating warming and record-breaking marine heatwaves, to faltering carbon sinks.

Between April 2023 and March 2024, global temperatures reached unprecedented levels – a surge that cannot be fully explained by the long-term warming trend and typical year-to-year fluctuations of the Earth’s climate. This suggests other factors are at play, such as declining sulphur emissions and shifting cloud cover.

(For more, Carbon Brief’s in-depth explainer of the drivers of recent exceptional warmth.)

Ocean heat uptake has climbed as well. This has intensified marine heatwaves, further stressing ecosystems and livelihoods that rely on fisheries and coastal resources.

The exceptional warming of the ocean has driven widespread impacts, including massive coral bleaching, fish and shellfish mortality and disruptions to marine food chains.

The map below illustrates some of the impacts of marine heatwaves from 2023-24, highlighting damage inflicted on coral reefs, fishing stocks and coastal communities.

Land “sinks” that absorb carbon – and buffer the emissions from human activity – are under increasing stress, too. Recent research shows a reduction in carbon stored in boreal forests and permafrost ecosystems.

The weakening carbon sinks means that more human-caused carbon emissions remain in the atmosphere, further driving up global temperatures and increasing the chances that warming will surpass the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C limit.

This links to the fourth insight, which shows how climate change and biodiversity loss can amplify each other by leading to a decrease in the accumulation of biomass and reduced carbon storage, creating a destabilising feedback loop that accelerates warming.

New evidence demonstrates that climate change could threaten more than 3-6 million species and, as a result, could undermine critical ecosystem functions.

For example, recent projections indicate that the loss of plant species could reduce carbon sequestration capacity in the range of 7-145bn tonnes of carbon over the coming decades. Similarly, studies show that, in tropical systems, the extinction of animals could reduce carbon storage capacity by up to 26%.

Human health and livelihoods

Growing pressure on the climate system is having cascading consequences for human societies and natural systems.

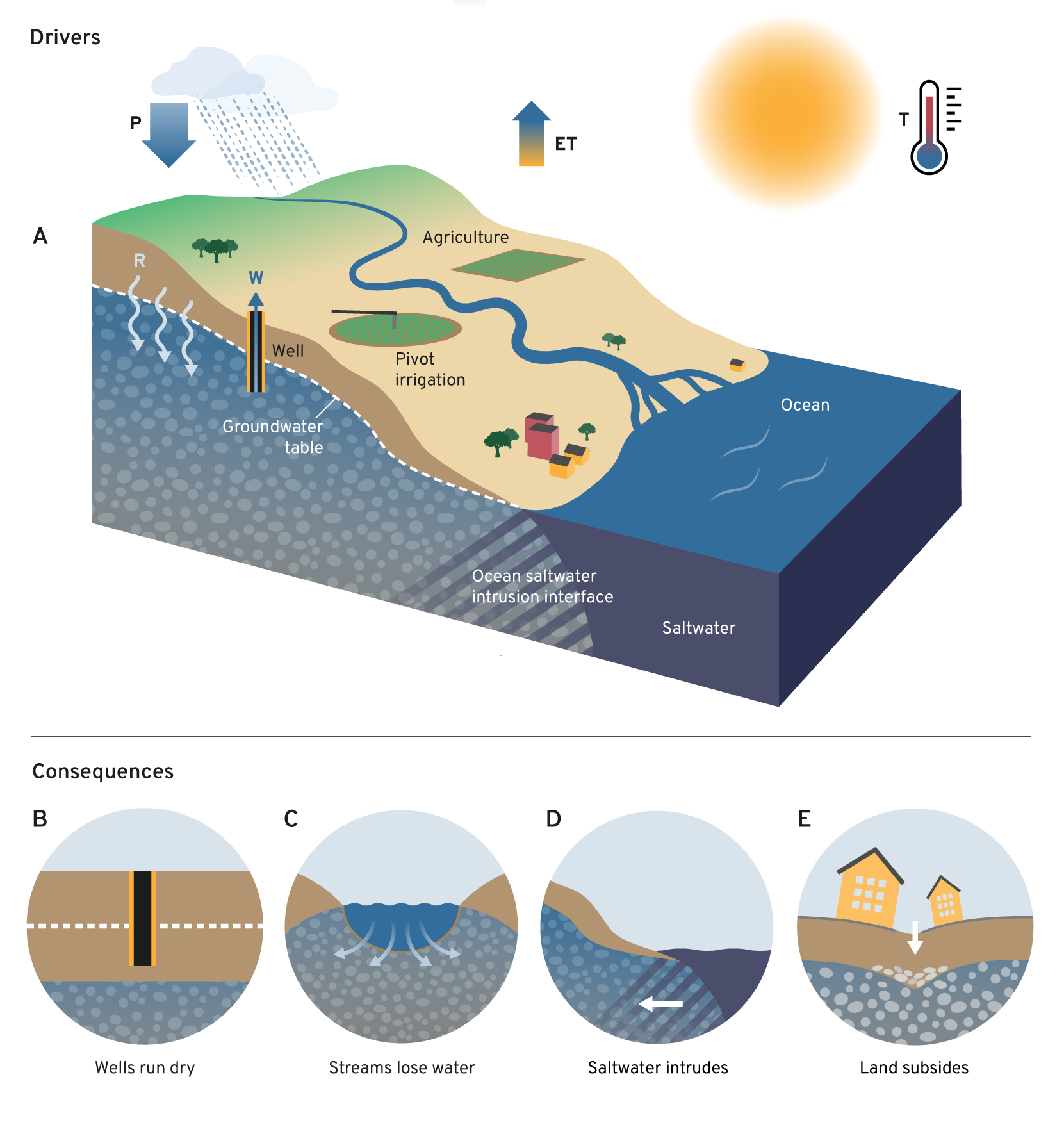

Our fifth insight highlights how groundwater supplies are increasingly at risk.

More than half the global population depends on groundwater – the second largest source of freshwater after polar ice – for survival.

But groundwater levels are in decline around the world. A 2025 Nature paper found that rapid groundwater declines, exceeding 50cm each year, have occurred in many regions in the 21st century, especially in arid areas dominated by cropland. The analysis also showed that groundwater losses accelerated over the past four decades in about 30% of regional aquifers.

Changes in rainfall patterns due to climate change, combined with increased irrigation demand for agriculture, are depleting groundwater reserves at alarming rates.

The figure below illustrates how climate-driven reductions in rainfall, combined with increased evapotranspiration, are projected to significantly reduce groundwater recharge in many arid regions – contributing to widespread groundwater-level declines.

These losses threaten food security, amplifying competition for scarce resources and undermining the resilience of entire communities.

Human health and livelihoods are also being affected by changes to the climate.

Our sixth insight spotlights the ongoing and projected expansion of the mosquito-borne disease dengue fever.

Dengue surged to the largest global outbreak on record in 2024, with the World Health Organization reporting 14.2m cases, which is an underestimate because not all cases are counted.

Rising temperatures are creating more favourable conditions for the mosquitoes that carry dengue, driving the disease’s spread and increasing its intensity.

The chart below shows the regions climatically suitable for Aedes albopictus (blue line) and Aedes aegypti (green line) – the primary mosquitoes species that carry the virus – increased by 46.3% and 10.7%, respectively, between 1951-60 and 2014-23.

The maps on the right reveal how dengue could spread by 2030 and 2050 under an emissions scenario broadly consistent with current climate policies. It shows that the climate suitable for the mosquito that spreads dengue could expand northwards in Canada, central Europe and the West Siberian Plain by 2050.

The ongoing proliferation of these mosquito species is particularly alarming given their ability to transmit the zika, chikungunya and yellow fever viruses.

Heat stress is also a growing threat to labour productivity and economic growth, which is the seventh insight in our list.

For example, an additional 1C of warming is projected to expose more than 800 million people in tropical regions to unsafe heat levels – potentially reducing working hours by up to 50%.

At 3C warming, sectors such as agriculture, where workers are outdoors and exposed to the sun, could see reductions in effective labour of 25-33% across Africa and Asia, according to a recent Nature Reviews Earth & Environment paper.

Meanwhile, sectors where workers operate in shaded or indoor settings could also face meaningful losses. This drain on productivity compounds socioeconomic issues and places a strain on households, businesses and governments.

Low-income, low-emitting regions are set to shoulder a greater relative share of the impacts of extreme heat on economic growth, exacerbating existing inequalities.

Action and policy

Our report illustrates not only the scale of the challenges facing humanity, but also some of the pathways toward solutions.

The eighth insight emphasises the critical role of carbon dioxide removal (CDR) in stabilising the climate, especially in “overshoot” scenarios where warming temporarily surpasses 1.5C and is then brought back down.

Scaling these CDR solutions responsibly presents technical, ecological, justice, equity and governance challenges.

Nature-based approaches for pulling carbon out of the air – such as afforestation, peatland rewetting and agroforestry – could have negative consequences for food security, biodiversity conservation and resource provision if deployed at scale.

Yet, research has suggested that substantially more CDR may be needed than estimated in the scenarios used in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC’s) last assessment report.

Recent findings showed that a pathway where temperatures remain below 1.5C with no overshoot would require up to 400Gt of cumulative CDR by 2100 in order to buffer against the effect of complex geophysical processes that can accelerate climate change. This figure is roughly twice the amount of CDR assessed by the IPCC.

This underscores the need for robust international coordination on the responsible scaling of CDR technologies, as a complement to ambitious efforts to reduce emissions. Transparent carbon accounting frameworks that include CDR will be required to align national pledges with international goals.

Similarly, voluntary carbon markets – where carbon “offsets” are traded by corporations, individuals and organisations that are under no legal obligation to make emission cuts – face challenges.

Our ninth insight shows how low-quality carbon credits have undermined the credibility of these largely unregulated carbon markets, limiting their effectiveness in supporting emission reductions.

However, emerging standards and integrity initiatives, such as governance and quality benchmarks developed by the Integrity Council for Voluntary Carbon Markets, could address some of the concerns and criticism associated with carbon credit projects.

High-quality carbon credits that are verified and rigorously monitored can complement direct emission reductions.

Finally, our 10th insight highlights how a mix of climate policies typically have greater success than standalone measures.

Research published in Science in 2024 shows how carefully tailored policy packages – including carbon pricing, regulations, and incentives – could consistently achieve larger and more durable emission reductions than isolated interventions.

For example, in the buildings sector, regulations that ban or phase out products or activities achieve an average effect size of 32% when included in a policy package, compared with 13% when implemented on their own.

Importantly, policy mixes that are tailored to the country context and with attention to distributional equity are more likely to gain public support.

These 10 insights in our latest edition highlight the urgent need for an integrated approach to tackling climate change.

The science is clear, the risks are escalating – but the tools to act are available.

The post Guest post: 10 key climate science ‘insights’ from 2025 appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Judge Rejects Trump Administration’s Plan to End NYC Congestion Pricing

A federal court ruled that the Trump administration’s efforts to end the program are unlawful. The federal government is reviewing its legal options, including an appeal.

A federal judge ruled Tuesday that the Trump administration’s efforts to shut down New York’s congestion pricing program are unlawful.

Judge Rejects Trump Administration’s Plan to End NYC Congestion Pricing

Climate Change

Gulf oil and gas crisis sparks calls for renewable investment

As well as claiming more than 550 lives, the war between the United States and Israel and Iran threatens to inflict severe economic damage across the world, by pushing up the oil, gas and energy prices.

About a fifth of the world’s oil and liquefied natural gas (LNG) passes on ships through the Strait of Hormuz, a narrow stretch of water separating Iran from the Gulf countries.

With Iranian missiles hitting oil and gas sites in the Gulf – including the world’s largest LNG export facility Ras Laffan – and fears that ships may be targeted, Qatar has halted its LNG production and traffic through the Strait has slowed drastically.

The disruption has sent oil and LNG prices surging, raising costs for households and businesses worldwide that rely on fossil fuels for electricity, transport, heating and manufacturing.

In two online briefings – focused on Europe and Asia, respectively – energy analysts warned journalists that prolonged disruption could trigger a global economic crisis. Governments should seek to reduce their reliance on oil and gas – through investments in clean energy and energy efficiency – rather than just seeking non-Gulf oil and gas suppliers, they said.

Seb Kennedy, founding editor of EnergyFlux.News, said the war is “a bonanza for US LNG exporters and a catastrophe for everyone else.” He added that “if this goes on for months and months then [the energy crisis] could be on the scale we saw in 2022”.

Asia hit hardest

Asian economies are expected to bear the brunt as the largest buyers of Qatari LNG. Research by ZeroCarbon Analytics suggests that Japan and South Korea, which get over three-fifths of their energy from oil and gas imports, are among the most vulnerable.

Sam Reynolds, a researcher from the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis said that Japan’s definition of energy security prioritises diversifying fossil fuel supply over promoting domestic renewables and, while Reynolds said this crisis could change that, he doubts that it will. Both Japan and South Korea are likely to speed up their pursuit of nuclear energy though, he added.

Nuclear comeback? Japan’s plans to restart reactors hit resistance over radioactive waste

Several South-East Asian nations – like Vietnam, the Philippines and Thailand – have invested in infrastructure to import LNG over the last few years in an attempt to gain energy security by diversifying supply routes beyond natural gas pipelines.

But ZeroCarbon Analytics researcher Amy Kong said that these countries were “seeing the same problems with new dealers” as “all the cards are held by a few LNG suppliers”. As these countries have huge untapped renewable potential, she said that “clean energy – not LNG – would be the key to avoiding impacts from these crises”.

Khondaker Golam, research director at Bangladesh’s Centre for Policy Dialogue, said Bangladesh’s already strained energy system will come under further pressure. In the short term, the government is likely to ration supply and seek LNG cargoes from outside the Gulf. Over time, however, the crisis could accelerate implementation of the country’s rooftop solar programme and other renewable projects.

China and India are also reliant on Gulf oil and gas and are now exploring alternative suppliers like Russia and, at least in India’s case, Canada and Norway. Over the longer term, Oxford University energy and climate professor Jan Rosenow said that China is also likely to double down on moving away from oil and gas by promoting electric vehicles, batteries and electrifying industries.

Although Europe imports a smaller share of its energy from the Gulf than Asia, it will not be insulated from price shocks. As Asian buyers compete for LNG cargoes – particularly from the US – gas prices will rise across the world, Kennedy added, with Europe already seeing increases.

Europe suffers too

Rosenow said that he was experiencing “deja vu” from when Russia restricted gas supplies to Europe, sparking a global energy crisis. Following that, he said, Europe had “not really managed to scale up the alternatives fast enough”, adding that “now we pay the price for that”.

He cited the example of Germany, where the government last week weakened requirements for buildings to install electric heat pumps instead of gas boilers. “We [in Europe] just haven’t made enough progress in terms of rolling out heat pumps, decarbonising industry and scaling up electric mobility,” he said.

Some in non-Gulf oil and gas producing countries have argued that this disruption justifies more production. Kennedy said the industry would “do everything it can to make that case”, but warned that new projects must consider demand decades ahead. By then, he said, “this conflict has probably long been forgotten about and we’re on to the next one”.

Uganda may see lower oil revenues than expected as costs rise and demand falls

In the United Kingdom, the government is under pressure from the right-wing opposition and US President Donald Trump to reverse its ban on licenses for new oil and gas fields in the North Sea.

But business secretary Peter Kyle said the crisis showed the UK must “double down” on renewables to protect its “sovereignty” as the crisis has exposed the country’s reliance on fossil fuels “from parts of the world which are fundamentally unstable”.

“We keep on seeing these lived examples of how instability, through regional instability, is creeping into our energy prices for which the British government has no agency”, he said.

Interest rates stymie renewables

But in the short term and without government policy intervention, Morningstar equity analyst Tancrède Fulop told Climate Home News that the crisis is likely to hold back the development of renewables.

This is because rising inflation from higher energy costs is likely to prompt governments to raise the cost of borrowing, he said. As renewables projects typically require large upfront capital investment, higher borrowing costs can undermine profitability.

Gas-fired power plants, by contrast, typically require lower initial investment than solar, wind or hydro, but higher operating costs over time, as fuel must be continuously purchased.

“What we saw between 2022 and 2024 with high inflation, high gas and power prices – a bit similar to today – renewable companies materially underperformed because of those high interest rates,” he said, “so all in all it won’t be as simple as oil and gas prices are surging so it’s good for renewables”.

The post Gulf oil and gas crisis sparks calls for renewable investment appeared first on Climate Home News.

Gulf oil and gas crisis sparks calls for renewable investment

Climate Change

US set to exit UN climate convention in February 2027

The United States is set to quit the world’s landmark climate convention next February, after the Trump administration formally notified the UN of its previously announced decision to withdraw.

UN Secretary-General António Guterres communicated last Friday that the UN treaty depository had received Washington’s formal notice to leave the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

Adopted in 1992 at the Rio Earth Summit, the climate treaty is the cornerstone of global efforts to curb climate change and tackle its impacts.

The US withdrawal will take effect on 27 February 2027 – one year after the formal notification – as required by the terms of the convention.

The US, the world’s second-largest emitter, will be the first nation to formally exit the treaty and the only one recognised by the UN outside of it.

‘Colossal own goal’

In January, President Donald Trump, who has called climate change a “con job”, announced his administration’s intention to quit the UNFCCC and 65 other international organisations and instruments, including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the most authoritative global voice on climate science, and the Green Climate Fund (GCF), the world’s largest multilateral climate fund.

A White House factsheet said President Trump was ending US participation in international organisations that “undermine America’s independence and waste taxpayer dollars on ineffective or hostile agendas”.

“Many of these bodies promote radical climate policies, global governance, and ideological programmes that conflict with US sovereignty and economic strength,” it added.

At the time, the UNFCCC chief Simon Stiell called the US decision to leave the convention “a colossal own goal which will leave the US less secure and less prosperous”.

“While all other nations are stepping forward together, this latest step back from global leadership, climate cooperation and science can only harm the US economy, jobs and living standards, as wildfires, floods, mega-storms and droughts get rapidly worse,” he added.

Relinquishing obligations

At the end of January 2026, the US already formally left the Paris Agreement, under which countries agreed in 2015 to try to limit global warming to “well below” 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to issue regular emissions-reduction plans. Trump pulled the US out of the accord in 2020 before President Biden re-joined it in 2021.

While the Trump administration had effectively already disengaged from global climate action immediately after its inauguration, its formal departure from the UNFCCC will free it from formal obligations, including reporting detailed greenhouse gas emissions inventories and providing funding for the convention.

The US already stopped funding the UNFCCC and failed to submit its emissions data last year. The federal administration also sent no delegates to the COP30 summit in Brazil last November.

Washington remains involved in other international negotiations with climate implications – including talks on a UN treaty to curb plastics pollution and efforts to price emissions in the shipping sector – where it has sought to slow progress and block binding global measures.

A route back in?

The US could potentially rejoin the UNFCCC in future, likely under a different administration, but there are different views on how complicated that process would be.

The US Senate ratified the UN climate convention – with no opposition – in 1992 and some experts believe a future president could rejoin the UNFCCC within 90 days of a formal decision based on the original “advice and consent” of the Senate.

But other legal experts told Carbon Brief that theory has never been tested in court and a new two-third majority vote in the Senate might be required, which would be challenging with the vast majority of Republican Senators currently opposed to membership.

The post US set to exit UN climate convention in February 2027 appeared first on Climate Home News.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits