The UK government has secured a record 7.4 gigawatts (GW) of solar, onshore wind and tidal power in its latest auction for new renewable capacity.

It is the second and final part of the seventh auction round for “contracts for difference” (CfDs), known as AR7a.

In the first part, held in January 2026, the government agreed contracts for a record 8.4GW of new offshore wind capacity.

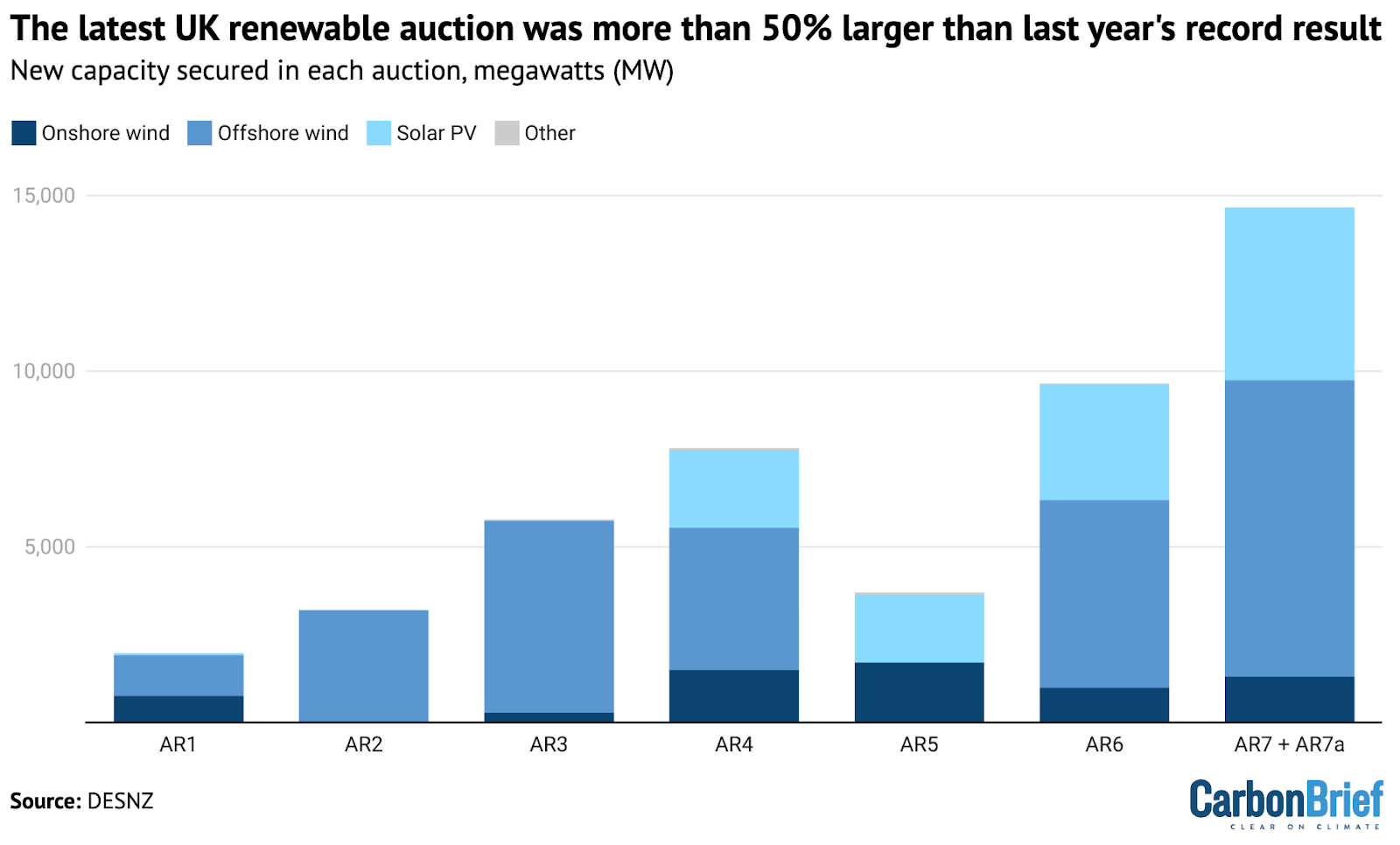

This makes AR7 the UK’s single-largest auction round overall, with its 14.7GW of new renewable capacity being 50% larger than the previous record set by AR6 in 2024.

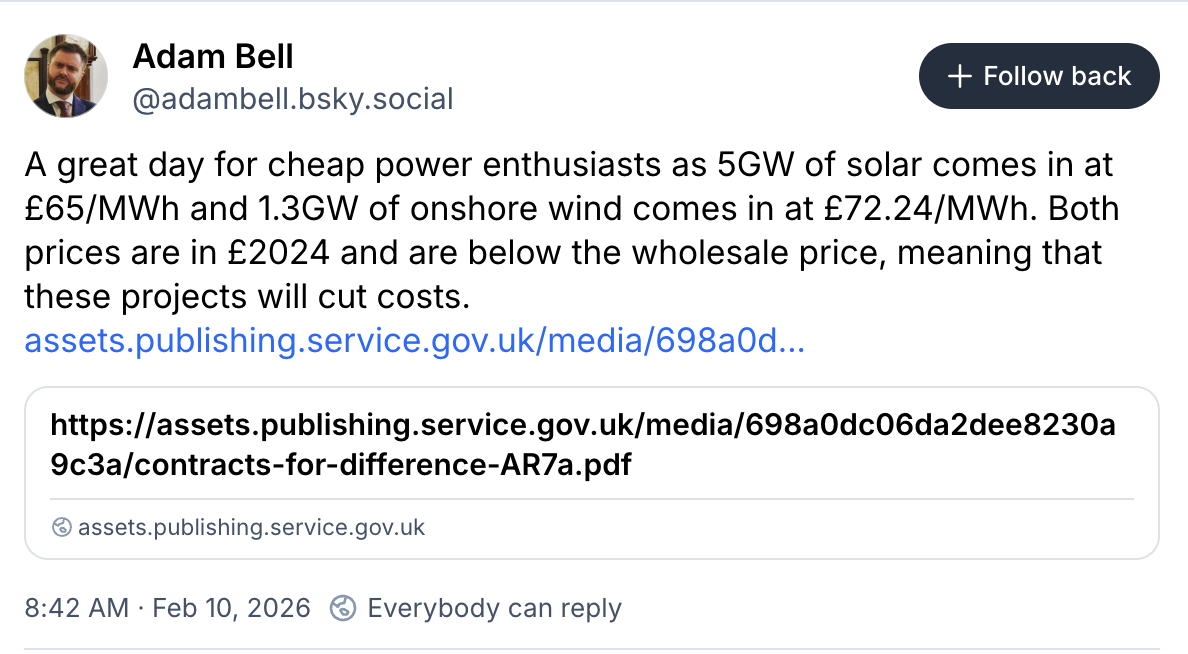

In AR7a, 157 solar projects secured contracts to supply electricity for £65 per megawatt hour (MWh) and 28 onshore wind projects were contracted at £72/MWh.

This means they will help cut consumer bills, according to multiple analysts.

Energy secretary Ed Miliband welcomed the outcome of the auction, saying in a statement that the new projects would be “50% cheaper” than new gas:

“These results show once again that clean British power is the right choice for our country, agreeing a price for new onshore wind and solar that is over 50% cheaper than the cost of building and operating new gas”.

In addition to cutting costs, the new projects will help reduce gas imports.

In total, AR7 will cut UK gas demand by around 90 terawatt hours (TWh) per year, enough to cut liquified natural gas (LNG) imports by two-thirds, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Below, Carbon Brief looks at the seventh auction results for onshore wind, solar and tidal, what they mean energy for bills and the impact of the UK’s target of “clean power by 2030”.

- What happened in the latest UK renewable auction?

- What does the solar and onshore wind auction mean for bills?

- What does it mean for energy security, jobs and investment?

- What does the auction mean for clean power by 2030?

What happened in the latest UK renewable auction?

The latest UK government auction for new renewable capacity is the second and final part of the seventh auction round, known as AR7a.

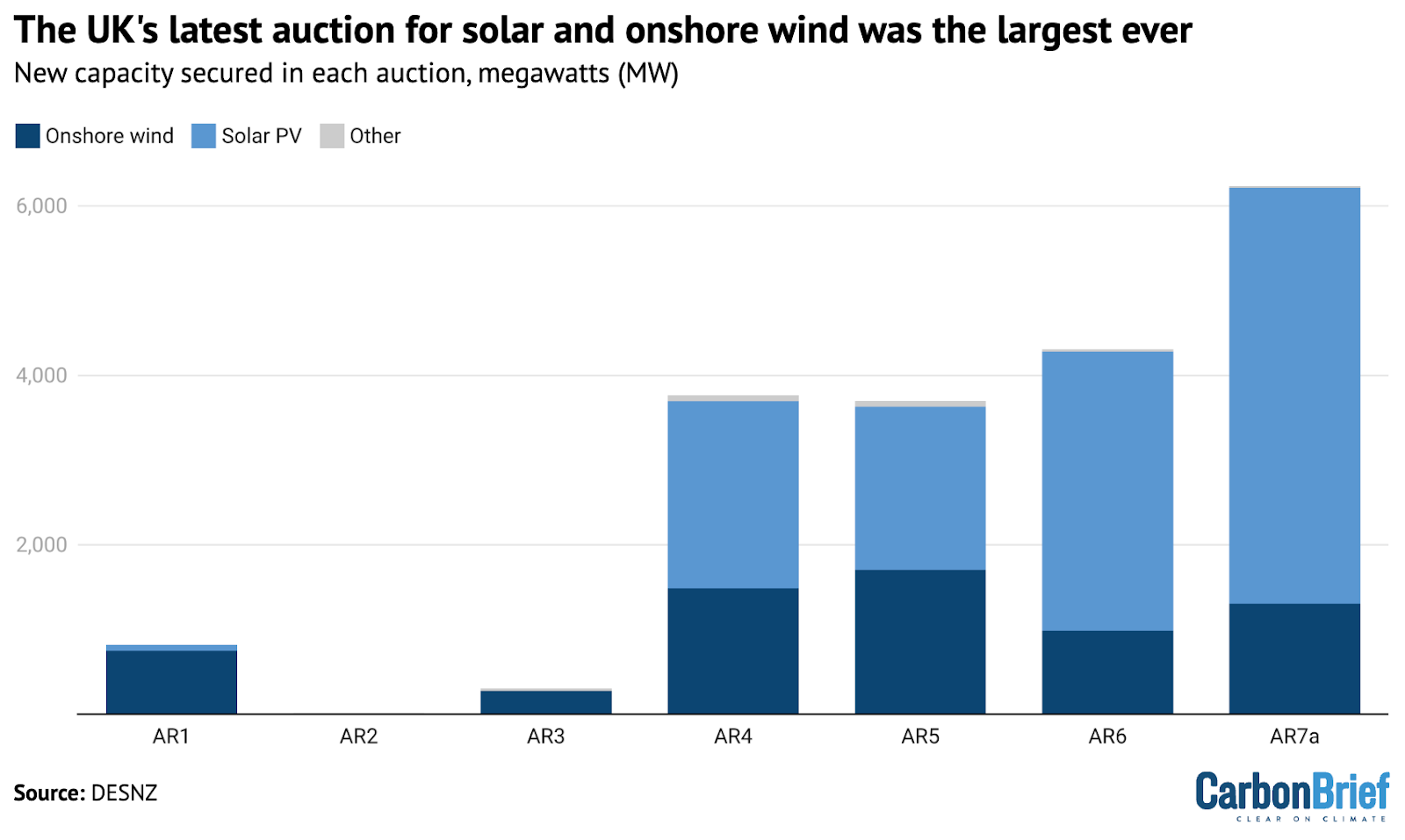

It secured a record 4.9GW of new solar capacity across 157 projects, as shown in the figure below, as well as 1.3GW of onshore wind across 28 projects.

In addition, four tidal energy projects totalling 21 megawatts (MW) secured contracts, included within “other” in the figure below.

Most of the solar that secured a contract has a capacity of less than 50MW. This is the cut-off point for projects to be approved by the local council. Larger schemes must instead go through the “nationally significant infrastructure project” (NSIP) process, subject to approval by the secretary of state for energy.

For the first time, one 480MW solar project – approved via this NSIP process – won a CfD in AR7a. The West Burton Solar NSIP is being developed in Lincolnshire and Nottinghamshire by Island Green Power. It is named after the grid connection it will use, freed up by the shuttering of the coal-powered West Burton plant.

However, Nick Civetta, project leader at Aurora Energy Research notes on LinkedIn that this site was only one of four eligible solar NSIPs to secure a contract.

Civetta adds that “wrangling these large projects into fruition is proving more painful than expected”.

Solar projects secured a “strike price” of £65/MWh in 2024 prices, some 7% cheaper than the £70/MWh agreed in the previous auction round.

In previous auction rounds CfD contracts were expressed in 2012 prices. For comparison, AR6 and AR7a solar contracts stand at £50/MWh and £47/MWh in 2012 prices, respectively.)

Alongside solar, 28 onshore wind projects secured contracts in the latest CfD auction, with a total capacity of 1.3GW.

This includes the Imerys windfarm in Cornwall, which at nearly 20MW is the largest onshore wind farm in England to secure a contract in a decade.

(Shortly after taking office in 2024, the current Labour government lifted a decade-long de facto ban on onshore wind in England.)

Overall, Scotland still dominated the auction for onshore wind, with 1,093MW of projects in the country in comparison to 38MW in England and 185MW in Wales.

This includes the Sanquhar II windfarm in Dumfries and Galloway in Scotland, which will become the fourth-largest onshore wind farm in the UK at 269MW.

In total, Wales secured contracts for 20 renewables projects in AR7a, with a capacity of more than 530MW. This is the largest ever number of Welsh projects to get backing in a CfD auction, according to a statement from the Welsh government.

Onshore wind secured a strike price of £72/MWh, up slightly from £71/MWh in the previous auction in 2024.

The prices for solar and onshore wind were 13% and 21% below the price cap set by Department of Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) for the auction, respectively.

In its press release announcing the results, the government noted that the results for solar and onshore wind were less than half of the £147/MWh cost of building and operating new gas power stations.

Finally, four tidal energy projects secured contracts with a total capacity of 21MW at a strike price of £265/MWh, up from £240/MWh in 2024.

In total, taken together with the 8.4GW of offshore wind secured in the first part of the auction, AR7 secured a total of 14.7GW of new clean power, as shown in the chart below.

This is enough to power the equivalent of 16 million homes, according to the government. It also makes AR7 the single-largest auction round by far, at more than 50% larger than the previous record set by AR6 in 2024.

This means that the two auction rounds held since the Labour government took office in July 2024 – AR6 and AR7 – have secured a total of 24GW of new renewable capacity. This is more than the 22GW from all previous auction rounds put together.

However, several analysts noted that the AR7a results did not include any old onshore windfarms looking to replace their ageing turbines with new equipment – so-called “repowering projects” – despite the auction being open to them for the first time.

What does the solar and onshore wind auction mean for bills?

Onshore wind and solar are widely recognised as the cheapest sources of new electricity generation in almost every part of the world.

The latest auction shows that the UK is no exception, despite its northerly location.

The prices for onshore wind and solar in the latest auction, at £72/MWh and £65/MWh respectively, are comfortably below recent wholesale power prices, which averaged £81/MWh in 2025 and £92/MWh in January 2026.

This means that the new projects will cut costs for UK electricity consumers, according to multiple analysts commenting on the auction outcome.

The government lauded the results of AR7a for securing “homegrown energy at good value for billpayers – once again proving that clean power is the right choice for energy security and to meet rising electricity demand”.

In a statement, Miliband added:

“By backing solar and onshore wind at scale, we’re driving bills down for good and protecting families, businesses, and our country from the fossil fuel rollercoaster controlled by petrostates and dictators. This is how we take back control of our energy and deliver a new era of energy abundance and independence.”

As noted in Carbon Brief’s coverage of the offshore wind results under AR7 in January, electricity demand is starting to rise as the economy electrifies and many of the UK’s existing power plants are nearing the end of their lives.

Therefore, new sources of electricity generation will be needed, whether from renewables, gas-fired power stations or from other sources.

In his statement, quoted above, Miliband said that the prices for onshore wind and solar were less than half the £147/MWh cost of electricity from new gas-fired power stations.

(This is based on recently published government estimates and assumes that gas plants would only be operating during 30% of hours each year, in line with the current UK fleet.)

Trade association RenewableUK also pointed to the cost of new gas, as well as the £124/MWh cost of the Hinkley C new nuclear plant, in its response to the auction results.

In a statement, Dr Doug Parr, policy director for Greenpeace UK, said:

“These new onshore wind and solar projects will supply energy at less than half the cost of new gas plants. Together with the new offshore wind contracts agreed last month, these cheaper renewables will lower energy bills as they come online.”

Strike prices for solar dropped by 6% compared to last year and while onshore wind prices rose, this was by less than 2% despite a “difficult environment for wind generation”, according to Bertalan Gyenes, consultant at LCP Delta.

In a post on LinkedIn, he noted that “extending the contract length [for onshore wind projects] by five years seems to have helped keep this increase low”.

The January offshore wind round secured 8.4 GW at £91/MWh, as such, the onshore and solar projects are 25% cheaper per unit of generation.

(The offshore wind projects secured in January are nevertheless expected to cut consumer bills relative to the alternative, or at worst to be cost neutral.)

Parr added that while the AR7a auction results “show we’re getting up to speed” ahead of the clean power 2030 target (see below), “an even faster way for the government to make a really big dent in bills would be to change the system that allows gas to set the overall energy price in this country”. He adds:

“That would allow us to unshackle our bills from unreliable petrostates and get off the rollercoaster of volatile gas markets once and for all.”

What does it mean for energy security, jobs and investment?

The onshore wind and solar projects secured in the latest auction round will generate an estimated 9 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

This is equivalent to roughly 3% of current UK electricity demand.

Combined with the estimated 37TWh from offshore wind secured during the first part of the auction, AR7 projects will be able to generate 46TWh of electricity, 14% of current demand.

If this electricity were to be generated by gas-fired power plants, then it would require around 90TWh of fuel, because much of the energy in the gas is lost during combustion.

This is several times more than the 25TWh of extra gas that could be produced in 2030 if new drilling licenses are issued, according to thinktank the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU). As such, AR7 will significantly cut UK gas imports, ECIU says, reducing exposure to volatile international gas markets.

Furthermore, ECIU says that the impact of renewables in driving down gas demand – and subsequently electricity prices – is already being seen in the UK.

Five years ago, gas was setting the wholesale price of power in the UK 98% of the time due to the way the electricity market operates.

This price-setting dominance is being eroded by renewables, with recent analysis from the UK Energy Research Centre showing that gas set power prices 90% of the time in 2025.

A further effect of new renewables is that they push the most expensive gas-fired power plants out of the system, reducing prices. This is known as the “merit-order effect”.

Recent analysis from ECIU found that large windfarms cut wholesale electricity prices by a third in 2025.

Lucy Dolton, renewable generation lead at Cornwall Insight, said in a statement that the AR7a results will provide a “surge in momentum as [the UK] pushes toward secure, homegrown energy”, adding:

“These investments ultimately strengthen the UK’s position against volatile gas markets. If the past few years have shown us anything, it’s that remaining tied to international energy markets comes with consequences.”

The projects that secured CfDs will help the UK avoid burning significant quantities of gas, “the bulk of which would have been imported at a cost which the UK cannot control”, said RenewableUK in its statement.

Together with previous CfD auction rounds, the latest new renewable projects are expected to generate some 155TWh of electricity once they are all operating, according to Carbon Brief analysis. This is around half of current UK demand.

Generating the same electricity from gas would require some 316TWh of fuel, which is similar to the 339TWh of gas produced by the UK’s North Sea operations in the most recent 12-month period for which data is available. This figure can also be compared with the 130TWh of gas that was imported by ship as liquified natural gas (LNG) in the same period.

The government added that the AR7a projects will support up to 10,000 jobs and bring £5bn in private investment to the UK.

(In total, the new projects secured via AR7 are expected to bring investments worth around £20-23bn to the UK, according to Aurora.)

Additionally, the onshore wind projects are expected to generate over £6.5m in “community benefit” funds for people living near them, according to RenewableUK.

The AR7a results were released alongside the publication of the Local Power Plan by the government and Great British Energy.

This is designed to provide £1bn in funding for communities to own and control their own clean energy projects across the UK.

What does the auction mean for clean power by 2030?

The AR7a results put the UK “on track for its 2030 clean power target”, according to the government.

Over AR6 and AR7, several changes have been made to the CfD process to help facilitate more projects to secure contracts.

A total of 24GW has been secured over the last two auction rounds – which have taken place under the current Labour government – compared to 22GW across the five auction rounds previously.

As part of its goal for clean power to meet 100% of electricity demand by 2030 and to account for at least 95% of electricity generation, the UK government is aiming for 27-29GW of onshore wind and 45-47GW of solar by the end of the decade.

As of September 2025, the UK had 16.3GW of installed onshore wind capacity and more than 21GW of solar capacity. Taken together, the onshore technologies therefore need to double in operational capacity over the next four years to reach the 2030 targets.

Analysis by RenewableUK suggests that the government will need to procure between 3.85GW to 4.85GW of onshore wind in the next two auctions for the 2030 goal to remain possible.

Writing on LinkedIn, Aurora’s Civetta said that the onshore clean power 2030 targets “remain a long way off”.

He continued that the gap for solar to reach its 45-47GW target is still a “whopping 18GW”, but added that there may be other ways for new capacity to be secured, beyond the CfD auctions.

He said these included a growing market for corporate “power purchase agreements” (PPAs), economic incentives for homes and businesses to install solar and the government’s recently released “warm homes plan”, all of which “should drive further procurement”.

Dolton from Cornwall Insight adds that “the challenge now is delivery”, continuing:

“2.5GW of the winners have a delivery year of 2027/28, and over half – 3.7GW – have a delivery year of 2028/29, which brings them very close to the government’s 2030 clean power target.

“Historically, renewable projects in the UK have faced delays, often due to grid connection backlogs and planning holdups. With AR7 and some of AR8 representing the only realistic pipeline for pre-2030 capacity, keeping to schedule will be essential.”

When built, the projects announced today will help to bring the total capacity of CfD-supported wind and solar to 50.6GW, according to Ember.

While solar and onshore wind are expected to play an important role in decarbonising the electricity system, offshore wind is set to be the “backbone”.

The government is targeting 43-50GW of offshore wind by 2030, up from around 17GW of installed capacity today.

This leaves a gap of 27-34GW to the government’s target range.

Prior to the AR7 auction, a further 10GW had already secured CfD contracts, excluding the cancelled Hornsea 4 project.

The 8.4GW secured in January brings the gap to reach the minimum of 43GW over the four years to just 7GW.

The post Q&A: New UK onshore wind and solar is ‘50% cheaper’ than new gas appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: New UK onshore wind and solar is ‘50% cheaper’ than new gas

Greenhouse Gases

Cropped 11 February 2026: Aftershocks of US withdrawals | Biodiversity and business risks | Deep-sea mining tensions

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter. Subscribe for free here. This is the last edition of Cropped for 2025. The newsletter will return on 14 January 2026.

Key developments

Economic risks from nature loss

RISKY BUSINESS: The “undervaluing” of nature by businesses is fuelling its decline and putting the global economy at risk, according to a new report covered by Carbon Brief. The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) “business and biodiversity” report “urg[ed] companies to act now or potentially face extinction themselves”, Reuters wrote.

BUSINESS ACTION: The report was agreed at an IPBES meeting in Manchester last week. Speaking to Carbon Brief at the meeting, IPBES chair, Dr David Obura, said the findings showed that “all sectors” of business “need to respond to biodiversity loss and minimise their impacts”. Bloomberg quoted Prof Stephen Polasky, co-chair of the report, as saying: “Too often, at present, what’s good for business is bad for nature and vice-versa.”

Tensions in deep-sea mining

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “Cropped” email newsletter. A fortnightly digest of food, land and nature news and views. Sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

JAPAN’S TAKEOFF: Japan’s prime minister, Sanae Takaichi, announced on 2 February that the country became the first in the world to extract rare earths from the deep seabed after successful retrievals near Minamitori Island, in the central Pacific Ocean, according to Asia Financial. The country hailed the move as a “first step toward industrialisation of domestically produced rare earth” metals, Takaichi said.

URGENT CALL: On 5 February, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) secretary general, Leticia Reis de Carvalho, called on EU officials to “quickly agree on an international rule book on the extraction of critical minerals in international waters”, due to be finalised later this year, Euractiv reported. The bloc has supported a proposed moratorium on deep-sea mining. However, the US has “taken the opposite approach”, fast-tracking a single permit for exploration and exploitation of seabed resources, and “might be pushing the EU – and others” to follow suit, the outlet added.

CAUTIONARY COMMENT: In the Inter Press Service, the former president of the Seychelles and a Swiss philanthropist highlighted the important role of African leadership in global ocean governance. It called for a precautionary pause on deep-sea mining due to the potential harmful effects of this extractive activity on biodiversity, food security and the economy. They wrote: “The accelerating push for deep-sea mining activities also raises concerns about repeating historic patterns seen in other extractive sectors across Africa.”

News and views

- ARGENTINE AUSTERITY: The Argentinian government’s response to the worst wildfires to hit Patagonia “in decades” has been hindered by president Javier Milei’s “gutting” of the country’s fire-management agency, the Associated Press reported. Carbon Brief covered a new rapid-attribution analysis of the fires, which found that climate change made the hot, dry conditions that preceded the fires more than twice as likely.

- CRISIS IN SOMALIA: The Somali government has begun “emergency talks” to address the drought that is gripping much of the country, according to Shabelle Media. The outlet wrote that the “crisis has reached a critical stage” amid “worsening shortages of water, food and pasture threatening both human life and livestock”.

- FOOD PRICES FALL: The UN Food and Agriculture Organization’s “food price index” – a measure of the costs of key food commodities around the world – fell in January for the fifth month in a row. The fall was driven by decreases in the price of dairy, meat and sugar, which “more than offset” increasing prices of cereals and vegetable oil, according to the FAO.

- HIGH STANDARDS: The Greenhouse Gas Protocol launched a new standard for companies to measure emissions and carbon removals from land use and emerging technologies. BusinessGreen said that the standard is “expected to provide a boost to the expanding carbon removals and carbon credit sectors by providing an agreed measurement protocol”.

- RUNNING OUT OF TIME: Negotiators from the seven US states that share the Colorado River basin met in Washington DC ahead of a 14 February deadline for agreeing a joint plan for managing the basin’s reservoirs. The Colorado Sun wrote: “The next agreement will impact growing cities, massive agricultural industries, hydroelectric power supplies and endangered species for years to come.”

- CORAL COVER: Malaysia has lost around 20% of its coral reefs since 2022, “with reef conditions continuing to deteriorate nationwide”, the Star – a Malaysian online news outlet – reported. The ongoing decline has many drivers, it added, including a global bleaching event in 2024, pollution and unsustainable tourism and development.

Spotlight

Aftershocks of US exiting major nature-science body

This week, Carbon Brief reports on the impacts of the US withdrawal from the global nature-science panel, IPBES.

The Trump administration’s decision to withdraw the US from the world’s main expert panel that advises policymakers on biodiversity and ecosystem science “harms everybody, including themselves”.

That’s according to Dr David Obura, chair of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, or IPBES.

IPBES is among the dozens of international organisations dealing with the fallout from the US government’s announcement last month.

The panel’s chief executive, Dr Luthando Dziba, told Carbon Brief that the exit impacts both the panel’s finances and the involvement of important scientists. He said:

“The US was one of the founding members of IPBES…A lot of US experts contribute to our assessments and they’ve led our assessments in various capacities. They’ve also served in various official bodies of the platform.”

Obura told Carbon Brief that “it’s very important to try and keep pushing through with the knowledge and keep doing the work that we’re doing”. He said he hopes the US will rejoin in future.

Carbon Brief attended the first IPBES meeting since Trump’s announcement, held last week in Manchester. At the meeting, countries finalised a new “business and biodiversity” report.

For the first time in the 14-year history of IPBES, there was no US government delegation present at the meeting, although some US scientists attended in other roles.

Cashflow impacts

Dziba is still waiting for official confirmation of the US withdrawal, but impacts were being felt even before last month’s announcement.

Budget information [pdf] from last October shows that the US contributed the most money to IPBES of any country in 2024 – around $1.2m. In 2025, when Trump took office, it sent $0, as of October.

Despite this, IPBES actually received around $1.2m extra funding from countries in 2025, compared to 2024, as other nations filled the gap.

The UK, for example, increased its contribution from around $367,000 in 2024 to more than $1.7m in 2025. The EU, which did not contribute in 2024 but tends to make multi-year payments, paid around $2.7m last year. These two payments made up the bulk of the increase in overall funding.

Wider effects of US exit

Dziba said IPBES is looking at other ways of boosting funds in future, but noted that lost income is not the only concern:

“For us, the withdrawal of the US is actually much larger than just the budgetary implications, because you can find somebody who can come in and increase the contribution and close that gap.

“The US has got thousands of leading experts in the fields where we undertake assessments. We know that some of them work for [the] government and maybe [for] those it will be more challenging for them to continue…But there are many other experts that we hope, in some way, will still be able to contribute to the work of the platform.”

One person trying to keep US scientists involved is Prof Pam McElwee, a professor of human ecology at Rutgers University. She told Carbon Brief that “there are still a tonne of American scientists and other civil society organisations that want to stand up”.

McElwee and others have looked at ways for US scientists to access funding to continue working with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which the US has also withdrawn from. She said they will try and do the same at IPBES, adding:

“It’s basically a bottom-up initiative…to make the message clear that scientists in the US still support these institutions and we still are part of them.

“Climate science is what it is and we can’t deny or withdraw from it. So we’ll just keep trying to represent it as best we can.”

Watch, read, listen

UNDER THE SEA: An article in bioGraphic explored whether the skeletons of dead corals “help or hinder recovery” on bleached reefs.

MOSSY MOORS: BBC News covered how “extinct moss” is being reintroduced in some English moors in an effort to “create diverse habitats for wildlife”.

RIBBIT: Scientists are “racing” to map out Ecuador’s “unique biological heritage of more than 700 frog species”, reported Dialogue Earth.

MEAT COMEBACK: Grist examined the rise and fall of vegan fine dining.

New science

- Areas suitable for grazing animals could shrink by 36-50% by 2100 due to continued climate change, with areas of extreme poverty and political fragility experiencing the highest losses | Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- The body condition of Svalbard polar bears increased after 2000, in a period of rapid loss of ice cover | Scientific Reports

- Studies projecting the possibility of reversing biodiversity loss are scarce and most do not account for additional drivers of loss, such as climate change, according to a meta-analysis of more than 55 papers | Science Advances

In the diary

- 9-12 February: Climate and cryosphere open science conference | Wellington, New Zealand

- 18 February: International conservation technology conference | Lima, Peru

- 22-27 February: American Geophysical Union’s ocean sciences meeting | Glasgow, UK

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz. Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 11 February 2026: Aftershocks of US withdrawals | Biodiversity and business risks | Deep-sea mining tensions appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

IPBES chair Dr David Obura: Trump’s US exit from global nature panel ‘harms everybody’

The Trump administration’s decision to withdraw the US from the intergovernmental science panel for nature “harms everybody, including them”, according to its chair.

Dr David Obura is a leading coral reef ecologist from Kenya and chair of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), the world’s authority on the science of nature decline.

In January, Donald Trump announced intentions to withdraw the US from IPBES, along with 65 other international organisations, including the UN climate science panel and its climate treaty.

In an interview with Carbon Brief, Obura says the warming that humans have already caused means “coral reefs are very likely at a tipping point” and that it is now inevitable that Earth “will lose what we have called coral reefs”.

A global goal to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030 will not be possible to achieve for every ecosystem, he continues, noting that a lack of action from countries means “we won’t be able to do it fast enough at this point”.

Despite this, it is still possible to reverse the “enabling drivers” of biodiversity decline within the next four years, he adds, warning that leaders must act as “our economies and societies fully depend on nature”.

The interview was conducted at the sidelines of an IPBES meeting in Manchester, UK, where governments agreed to a new report detailing how the “undervaluing” of nature by businesses is fuelling biodiversity decline and putting the global economy at risk.

- On US leaving IPBES: “Any major country not being part of it harms everybody, including themselves.”

- On reversing nature loss by 2030: “We won’t be able to do it fast enough at this point.”

- On the value of biodiversity: “Nature is really the life support system for people. Our economies and societies fully depend on nature.”

- On coral reefs: “We will lose what we have called coral reefs up until this point.”

- On nature justice: “The places that are most vulnerable don’t have the income, or the assets, to conserve biodiversity.”

- On IPBES’s latest report: “One of the key findings is all businesses have impacts and dependencies on nature.”

- On the next UN nature summit: “We need acceleration of activities and impact and effectiveness, more than anything else.”

Carbon Brief: Last month Trump announced plans for the US to exit IPBES and dozens of other global organisations. You described this at the time as “deeply disappointing”. What are your thoughts on the decision now and what will be the main impacts of the US leaving IPBES?

David Obura: Well, part of the reason that I’ve come to IPBES is because, of course, I believe in the multilateral process, because we bring 150 countries together, we’re part of the UN and the multilateral system and we’re based on knowledge [that provides] inputs to policymaking. We have a conceptual framework that looks from the bottom up on how people depend on nature. I’m also doing a lot of science on Earth systems at the planetary level, how our footprint is exceeding the scale of the planet. We have to make decisions together. We need the multilateral system to work to help facilitate that. It has never been perfect. Of course, I come from a region [Kenya] that hasn’t been, you know, powerful in the multilateral process.

But we need countries to come together, so any major country not being part of it harms everybody, including themselves. It’s very important to try and keep pushing through with the knowledge and keep doing the work that we’re doing, so that, over time, hopefully [the US will] rejoin. Because, in the end, we will really need that to happen.

CB: This is the first IPBES meeting since Trump made the announcement. Has it had an impact so far on these proceedings and is there any kind of US presence here?

DO: This plenary is like every plenary that we have had. The current members are here. Some members are not. And, of course, we have some states here as observers working out if they’re going to join or not. And then we have a lot of private sector observers and universities and so on. The impact of a country leaving – the US in this case – has no impact on the plenary itself, because they’re not here making decisions on the things that we do.

We, of course, don’t have US government members attending in technical areas, but we do have institutions and universities and academics here attending as they have in the past. So, in that sense, the plenary goes on as it goes on – the science and the knowledge is the same. The decision-making processes we have here are the same. And, as I said earlier, what has an impact is the actual action that takes place afterwards, because a lot of the recommendations that we make are based on enabling conditions that governments put in place, to bring in place sustainability actions and so on. When governments are not doing that, especially major economic drivers, then the whole system suffers.

CB: When you were appointed as chair of IPBES more than two years ago, you said that your aim was to strengthen cohesion and impact and also get the findings of IPBES in front of more people. So how would you rate your progress on this now that it’s been about a couple of years?

DO: Well, like any intergovernmental process, we have a certain amount of inertia in what we do and it takes a few years to consult on topics for assessments and then to do them and to improve them and get them out.

One of the main things we’re discussing right now is we have had a rolling work programme from when IPBES started until 2030 and we need to decide on the last few deliverables and how we work in that period. We are asking for a mandate to spend the next year really considering the multiple options that we have in proposing a way forward for the last few years of this work programme. I feel that the countries are very aligned. We have done a lot of work, produced a lot of outputs. It is challenging for governments and other stakeholders to read our assessments and reach into them to find what’s useful to them. They make constant calls for more support, in uptake, in capacity building and in policy support.

The second global assessment in 2028 will be our 17th assessment [overall]. We would like to focus on really bringing all this knowledge together across assessments in ways that are relevant to different governments, different stakeholder groups, different networks to help them reach into the knowledge that’s in the assessments. And I think the governments, of course, want that as well, because many of them are calling for it. Many of the governments that support us financially, of course, want to see a return of investment on the money that they have put in.

CB: Nations agreed to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. Back in 2023 we had a conversation for Carbon Brief and you said that you were “highly doubtful” this goal could be achieved for every ecosystem by that date. Where do you stand on this now?

DO: I work on coral reefs and part of the reason I’ve come to IPBES platform is because the amount of climate change we’re committed to with current fossil fuel emissions and the focus on economic growth means that corals will continue to decline 20, 30, 40 years into the future. I think of that there’s no real doubt. The question is how soon we put in place the right actions to halt climate change. That will then have a lag on how long it takes for corals to cope with that amount of climate change.

We can’t halt and reverse the decline of every ecosystem. But we can try and bend the curve to halt and reverse the drivers of decline. So, that’s some of the economic drivers that we talk about in the nexus and transformative change assessment, the indirect drivers and the value shifts we need to have. What the Global Biodiversity Framework [GBF, a global nature agreement made in 2022] aspires to do in terms of halting and reversing biodiversity decline – we absolutely need to do that. We can do it and we can put in place the enabling conditions for that by 2030 for sure. But we won’t be able to do it fast enough at this point to halt [the loss of] all ecosystems.

We’re now in 2026, so this is three years plus after the GBF was adopted. We still need greater action from all countries and all stakeholders and businesses and so on. That’s what we’re really pushing for in our assessments.

CB: Biodiversity loss has historically been underappreciated by world leaders. As the world continues to be gripped by geopolitical uncertainty, conflict and financial pressures, what are your thoughts on the chances of leaders addressing the issue of biodiversity loss in a meaningful way?

DO: What are the chances of addressing biodiversity loss? I mean, we have to do it. It’s really our life support system and if we only focus on immediate crises and threats and don’t pay attention to the long-term threats and crises, that only creates more short-term crises down the line, we make it harder and harder to do that. I hope that what I’m hoping we get to understand better through IPBES science, as well as others, is that we’re not just reporting on the state of biodiversity because it’s nice to have it, but it’s [because] diversity of nature is really the life support system for people. Our economies and societies fully depend on nature. If we want them to prosper and be secure into the long-term future, we have to learn how to bring the impact and dependencies of business, which is a focus of this assessment, in line with nature. And until we do that, we will just continue to magnify the potential for future crises and their impacts.

CB: You mentioned already that your expertise is in coral reefs. A report last year warned that the world has reached its first climate tipping point, that of widespread dying of warm water coral reefs. Do you agree with that statement and can you discuss the wider state of coral reefs across the world at this present moment?

DO: The report that came out last year in 2025 was a global tipping point report and it’s actually in 2023 the first one of those [was published]. I was involved in that one and we basically took what the IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] has produced, which [is] compiled from the [scientific] literature [which said] that 1.5-2C was the critical range for coral reefs, where you go from losing 70-90% to 90-99% of coral reefs around the world. [It is] a bit hard to say exactly what that means. What we did was we actually reduced that range from 1.5C-2C to 1-1.5C, based on observations we’ve already made about loss of corals. In 2024, the world was 1.5C above historical conditions for one year. The IPCC number requires a 20-year average [for 1.5C to be crossed]. So, we’re not quite at the IPCC limit, but we’re very close. Also, with not putting in place fast enough emission reductions, warming will continue.

Coral reefs are very likely at a tipping point. And, so, I do agree with the statement. It means that we lose the fully connected regional, global system that coral reefs have been in the past. There will still be some coral reefs in places that have some natural protection mechanisms, whether it’s oceanographic or some levels of sedimentation in green water from rivers can help. And there’s resilience of corals as well. Some corals will be able to adapt somewhat, but not all – and not all the other species too. We will lose what we have called coral reefs up until this point. We’ll still continue to have simpler coral ecosystems into the future, but they won’t be quite the same.

It is a crisis point and my hope is that, in coming out from the coral reef world, I can communicate that this is, this has been a crisis for coral reefs. It’s a very important ecosystem, but we don’t want it to happen to more and more and more ecosystems that support more [than] hundreds of millions and billions of people as well. Because, if we let things go that far, then, of course, we have much bigger crises on our hands.

CB: Something else you’ve spoken about before is around equity being one of the big challenges when it comes to responding to biodiversity loss. Can you explain why you think that biodiversity loss should be seen as a justice issue?

DO: Well, biodiversity loss is a justice issue because we are a part of biodiversity and – just like the loss of ecosystems and habitats and species – people live locally as well. People experience biodiversity loss in their surroundings.

The places that are most vulnerable and don’t have the income, or the assets, to either conserve biodiversity, or need to rely on it too much so they degrade it – they feel the impacts of that loss much more directly than those who do have more assets. Also, the more assets you have, the more you can import biodiversity products and benefits from somewhere else.

So, it’s very much a justice issue, both from local levels experiencing it directly, but then also at global levels. We are part of it [biodiversity], we don’t own it. It’s a global good, or a common public good, so we need to be preserving it for all people on the planet. In that sense, there are many, many justice issues that are involved in both loss of biodiversity and how you deal with that as well.

CB: How would you say IPBES is working towards achieving greater equity in biodiversity science?

DO: One of the headline findings of our values assessment in 2022, which looked at multiple values different cultures have and different worldviews around the planet, [was that] by accommodating or considering different worldviews and different perspectives, you achieve greater equity because you’re already considering other worldviews in making decisions.

So, that’s an important first step – just making it much more apparent and upfront that we can’t just make decisions, especially global ones, from a single worldview and the dominant one is the market economic worldview that we have. That’s very important.

But, then, also in how we do our assessments and the knowledge systems that are incorporated in them. We integrate different knowledge systems together and try and juxtapose – or if they can be integrated, we do that, sometimes you can’t – but you just need to illustrate different worldviews and perspectives on the common issue of biodiversity loss or livelihoods or something like that.

We hope that our conceptual framework and our values framework really help bring in this awareness of multiple cultures and multiple perspectives in the multilateral system.

CB: When this interview is published, IPBES will have released its report on business and biodiversity. What are some of the key takeaways from this?

DO: Our assessments integrate so much information that the key messages are actually, in retrospect, quite obvious in a way. One of the key findings it will say is that all businesses have impacts and dependencies on nature.

Of course, when you think about it, of course they do. We often think, “oh, well ecotourism is dependent on nature”, but even a supermarket is dependent on nature because a lot of the produce comes from a natural system somewhere, maybe in a greenhouse or enhanced by fertiliser, but it still comes from natural systems. Any other business will have either impacts on the nature around it, or it needs tree shade outside so people can walk in and things like that.

So, that’s one of the main findings. It’s not just certain sectors that need to respond to biodiversity loss and minimise their impacts. All sectors need to. Another finding, of course, is that it’s very differentiated depending on the type of business and type of sector.

It’s also very differentiated in different parts of the world in terms of responsibilities and also capabilities. So small businesses, of course, have much less leeway, perhaps, to change what they’re doing, whereas big businesses do and they have more assets, so they can deal with shifts and changes much better.

It’s a methodological assessment, rather than assessing the state of businesses, or the state of nature in relation to businesses [and] they pull together a huge list of methodologies and tools and things that businesses can access and do to understand their impacts and dependencies and act on them. Then [there is] also guidance and advice for governments on how to enable businesses to do that with the right incentives and regulations and so on. In that sense, it helps bring knowledge together into a single place.

It has been fantastic to see the parallel programme that the UK government has organised [at the IPBES meeting in Manchester]. It has brought together a huge range of British businesses and consultancies and so on that help businesses understand their impacts on nature. There’s a huge thirst.

To some extent, I would have thought, with so much capacity already in some of these organisations, what would they learn from our assessments? But they’re really hungry to see the integration. They really want to see that this really does make a big difference, that others will do the same, that the government will really support moving in these directions. There’s a huge amount of effort in the findings coming out and I’m sure that that will be felt all around the world and in different countries in different ways.

CB: As we’re speaking now, you’re still in the midst of figuring out exactly what the report will say and going through line-by-line to figure this out. Something we’ve seen at other negotiations…has been these entrenched views from countries on certain key issues. And one thing I did notice in the Earth Negotiations Bulletin discussion of yesterday’s [4 February] negotiations was that it said that some delegations wanted to remove mentions of climate change from the report. Has this been a key sticking point here or have there been any difficulties from countries during these negotiations?

DO: The nature of these multilateral negotiations is that the science is, in a way, a central body of work that is built through consensus of bringing all this knowledge together. It’s almost like a centralising process. And, yes, different countries have different perspectives on what their priorities are and the messages they want to see or not.

We still, of course, deal with different positions from countries. What we hope to do is to be able to convene it so that we see that we serve the countries best by having the most unbiased reporting of what the science is saying in language that is accessible to and useful to policymakers, rather than not having language or not having mention of things in in the agreed text.

How it’ll work out, I don’t know. Each time is different from the others. I think one of the key things that’s really important for us is that you do have different governance tracks on different aspects of the world we deal in. So, the [UN] Sustainable Development Goals, as well [as negotiations] on climate change – the UNFCCC, the climate convention, is the governing body for that. There’s two goals on nature – the Convention on Biological Diversity and other multilateral agreements are the institutions that govern that part.

We have come from a nature-based perspective, with nature’s contributions to a good quality of life for people…We start in the nature goals, but we actually have content that relates to all the other goals. We need to consider climate impacts on nature, or climate impacts on people that affect how they use nature. The nexus assessment was, in a way, a mini SDG report. It looked at six different Sustainable Development Goals.

We try and make sure that while on the institutional mechanisms, certain countries may try and want us to report within our mandate on nature, we do have findings that relate to climate change that relate to income and poverty and food production and health systems [and] that we need to report [outwardly] so that people are aware of those and they can use those in decision-making contexts.

That’s a difficult discussion and every time it comes out a little bit differently. But we hope we move the agenda further towards 2030 in the SDGs. We have an indivisible system that we need to report on.

CB: The next UN biodiversity summit COP17 is taking place later this year. What are the main outcomes you’re hoping to see at that summit?

DO: The main outcomes I would hope to see from the biodiversity summit is greater alignment across the countries. We really need to move forward on delivering on the GBF as part of the sustainable development agenda as well. So there will be a review of progress. We need acceleration of activities and impact and effectiveness, more than anything else.

That means, of course, addressing all of the targets in the GBF. Not equally, necessarily, but they all need progress to support one another in the whole. We work to provide the science inputs that can help deliver that through the CBD [Convention on Biological Diversity] mechanisms as well. We hope they use our assessments to the fullest and that we see good progress coming out.

CB: Great, thank you very much for your time.

The post IPBES chair Dr David Obura: Trump’s US exit from global nature panel ‘harms everybody’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

IPBES chair Dr David Obura: Trump’s US exit from global nature panel ‘harms everybody’

Greenhouse Gases

Climate change made ‘fire weather’ in Chile and Argentina three times more likely

The hot, dry and windy weather preceding the wildfires that tore through Chile and Argentina last month was made around three times more likely due to human-caused climate change.

This is according to a rapid attribution study by the World Weather Attribution (WWA) service.

Devastating wildfires hit multiple parts of South America throughout January.

The fires claimed the lives of 23 people in Chile and displaced thousands of people and destroyed vast areas of native forests and grasslands in both Chile and Argentina.

The authors find that the hot, dry and windy conditions that drove the “high fire danger” are expected to occur once every five years, but that these conditions would have been “rarer” in a world without climate change.

In today’s climate, rainfall intensity during the “fire season” is around 20-25% lower in the areas covered by the study than it would be in a world without human-caused emissions, the study adds.

Study author Prof Friederike Otto, professor of climate science at Imperial College London, told a press briefing:

“We’re confident in saying that the main driver of this increased fire risk is human-caused warming. These trends are projected to continue in the future as long as we continue to burn fossil fuels.”

‘Significant’ damage

The recent wildfires in Chile and Argentina have been “one of the most significant and damaging events in the region”, the report says.

In the lead-up to the fires, both countries were gripped by intense heatwaves and droughts.

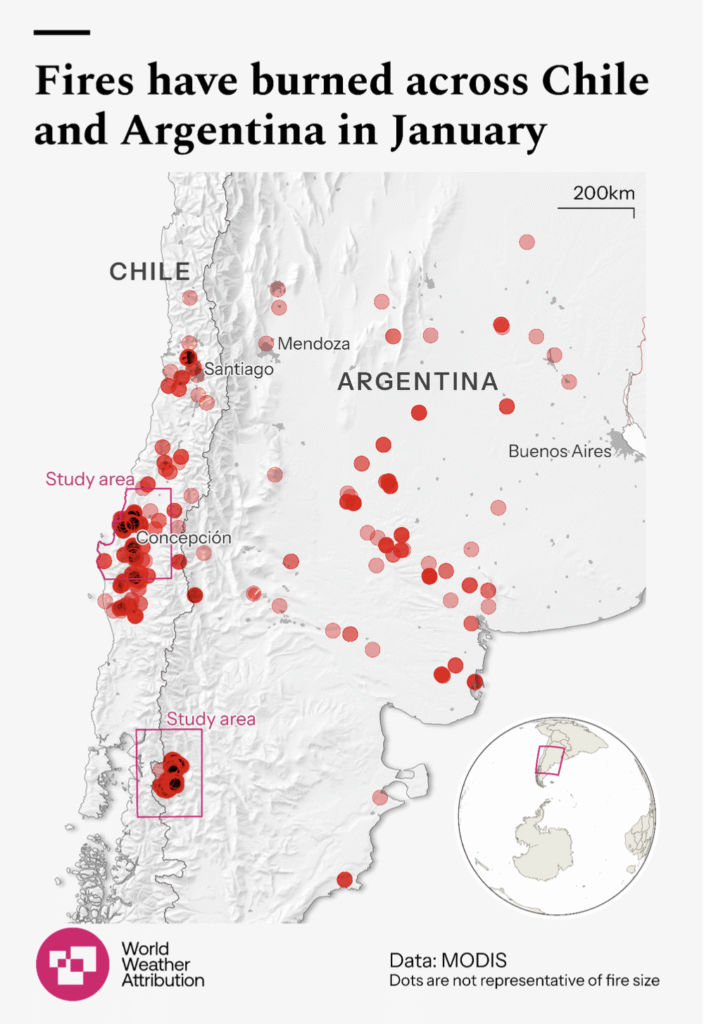

The authors analysed two regions – one in central Chile and the other in Argentine Patagonia, along the border between Argentina and Chile.

For example, in Argentina’s northern Patagonian Andes, the last recorded rainfall was in mid-November of 2025, according to the report. It adds that in early January, the region recorded 11 consecutive days of “extreme maximum temperatures”, marking the “second-longest warm spell in the past 65 years”.

Dr Juan Antonio Rivera, a researcher at the Argentine Institute of Snow Science, Glaciology and Environmental Sciences, told a WWA press briefing that these weather conditions dried out vegetation and decreased soil moisture, which meant that the fires “found abundant fuel to continue over time”.

In the northern Patagonian Andes of Argentina, wildfires started on 6 January in Puerto Patriada and spread over two national parks of Los Alerces and Lago Puelo and nearby regions. These fires remained active into the first week of February.

The fires engulfed more than 45,000 hectares of native and planted forest, shrublands and grasslands, including 75% of native forests in the village of Epuyén, notes the study.

At least 47 homes were burned, according to El País. La Nación reported that many families evacuated themselves to prevent any damage.

In south-central Chile, wildfires occurred from 17 to 19 January, affecting the Biobío, Ñuble and Araucanía regions.

They started near Concepción city, the capital of the Biobío region, where maximum temperatures reached 26C. In the nearby city of Chillán, temperatures reached 37C.

From there, the fires spread southwards to the coastal towns of Penco-Lirquen and Punta Parra, in the Biobío region.

The event left 23 people dead, 52,000 people displaced and more than 1,000 homes destroyed in the country, according to the study.

These wildfires burnt more than 40,000 hectares of forests, “tripling the amount of land burned in 2025” across the country, reported La Tercera.

The study adds that more than 20,000 hectares of non-native forest plantations, including Monterey pine and Eucalyptus trees, were consumed by the blaze and critical infrastructure was affected.

A WWA press release points out that the expansion of non-native pines and invasive species “has created highly flammable landscapes in Chile”.

Hot, dry and windy

Wildfires are complex events that are influenced by a wide range of factors, such as atmospheric moisture, wind speed and fuel availability.

To assess the impact of climate change on wildfires, the authors chose a “fire weather” metric called the “hot dry windy index” (HDWI). This combines maximum temperature, relative humidity and wind speed.

While this metric does not include every component that could contribute to intense wildfires, such as land-use change and fuel load data, study author Dr Claire Barnes from Imperial College London told a press briefing that HDWI is “a very good predictor of short-term, extreme, dry, fire-prone conditions”.

The authors chose to analyse two separate regions. The first lies along the coast and the foothills of the Andes around the Ñuble, Biobío and La Araucanía regions in central Chile. The second sits across the Chilean and Argentine border in Patagonia.

These regions are shown on the map below, where red circles indicate the wildfires recorded in January 2026 and pink boxes represent the study areas.

The authors also selected different time periods for the two study regions, to reflect the “different lengths of peak wildfire activity associated with the fires in each region”.

For the central Chilean study area, the authors focus their analysis on the two most severe days of HDWI, 17-18 January. For the Patagonian region, they focus on the most severe five-day period, which took place over 2-6 January.

To put the wildfire into its historical context, the authors analyse data on temperature, wind and rainfall to assess how HDWI over the two regions has changed since the year 1980.

They find that in both study regions, the high HWDI recorded in January is not “particularly extreme” in today’s climate and would typically be expected roughly once every five years. However, they add that the event would have been “rarer” in a world without climate change, in which average global temperatures are 1.3C cooler.

The authors also use a combination of observations and climate models to carry out an “attribution” analysis, comparing the world as it is today to a “counterfactual” world without human-caused climate change.

They find that climate change made the high HDWI three-times more likely in the central Chilean region and 2.5-times more likely in the Patagonian region.

The authors also conduct analysis focused solely on November-January rainfall.

Both study regions experienced “very low rainfall” in the months leading up to the fires, the authors say. They find that fire-season rainfall intensity is around 25% lower in the central Chilean region and 20% lower in the Patagonia region in today’s climate than it would have been in a world without climate change.

Finally, the authors considered the influence of climatic cycles such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), a naturally occurring phenomenon that affects global temperatures and regional weather patterns.

They find that a combination of La Niña – the “cool” phase of ENSO – combined with another natural cycle called the Southern Annular Mode, led to atmospheric circulation patterns that “favoured the hot and dry conditions that enhanced fire persistence and severity in parts of the region”.

However, they add that this has a comparably small effect on the overall intensity of the wildfires, with climate change standing out as the main driver.

(These findings are yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal. However, the methods used in the analysis have been published in previous attribution studies.)

Vulnerable communities

The wildfires affected native forests, national parks and small rural and tourist communities in both countries.

A 2025 study conducted in Chile, cited in the WWA analysis, found that 74% of survey respondents did not have appropriate education and awareness on wildfires.

This suggests that insufficient preparedness on early warning signs, response measures and prevention can “exacerbate the severity and frequency of these events”, the WWA authors say.

Aynur Kadihasanoglu, senior urban specialist at the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Center, said in the WWA press release that many settlements in Chile are close to flammable pine plantations, which “puts lives and livelihoods at risk”.

Additionally, the head of Chile’s National Forest Corporation pointed to “structural shortcomings” in fire prevention, such as lack of regulation in lands without management plans, reported BioBioChile.

In Argentina, the response to the fires has been hampered by large budget cuts and reductions in forest rangers, according to the WWA press release. Experts have criticised Argentina’s self-styled “liberal-libertarian” president Javier Milei for the cuts and the delay to declaring a state of emergency in Patagonia.

According to the Associated Press, “Milei slashed spending on the National Fire Management Service by 80% in 2024 compared to the previous year”. The service “faces another 71% reduction in funds” in its 2026 budget, the newswire adds.

Argentinian native forests and grasslands are experiencing “intense pressure” from wildfires, according to the study. Many vulnerable native animal species, such as the huemul and the pudú, are losing critical habitat, while birds, such as the Patagonian black woodpecker, are losing nesting sites.

The post Climate change made ‘fire weather’ in Chile and Argentina three times more likely appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate change made ‘fire weather’ in Chile and Argentina three times more likely

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Renewable Energy2 years ago

GAF Energy Completes Construction of Second Manufacturing Facility