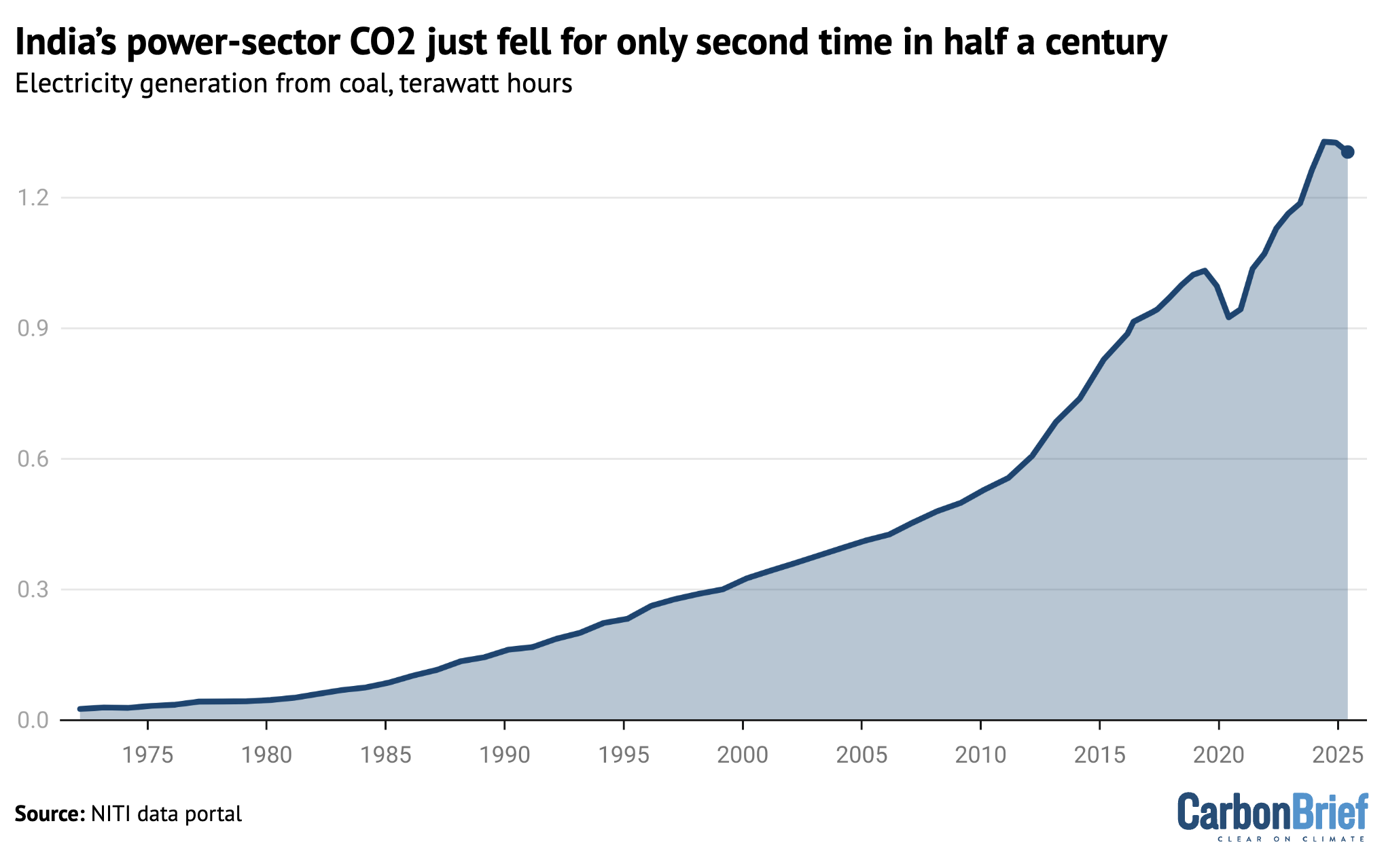

India’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from its power sector fell by 1% year-on-year in the first half of 2025 and by 0.2% over the past 12 months, only the second drop in almost half a century.

As a result, India’s CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and cement grew at their slowest rate in the first half of the year since 2001 – excluding Covid – according to new analysis for Carbon Brief.

The analysis is the first of a regular new series covering India’s CO2 emissions, based on monthly data for fuel use, industrial production and power output, compiled from numerous official sources.

(See the regular series on China’s CO2 emissions, which began in 2019.)

Other key findings on India for the first six months of 2025 include:

- The growth in clean-energy capacity reached a record 25.1 gigawatts (GW), up 69% year-on-year from what had, itself, been a record figure.

- This new clean-energy capacity is expected to generate nearly 50 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity per year, nearly sufficient to meet the average increase in demand overall.

- Slower economic expansion meant there was zero growth in demand for oil products, a marked fall from annual rates of 6% in 2023 and 4% in 2024.

- Government infrastructure spending helped accelerate CO2 emissions growth from steel and cement production, by 7% and 10%, respectively.

The analysis also shows that emissions from India’s power sector could peak before 2030, if clean-energy capacity and electricity demand grow as expected.

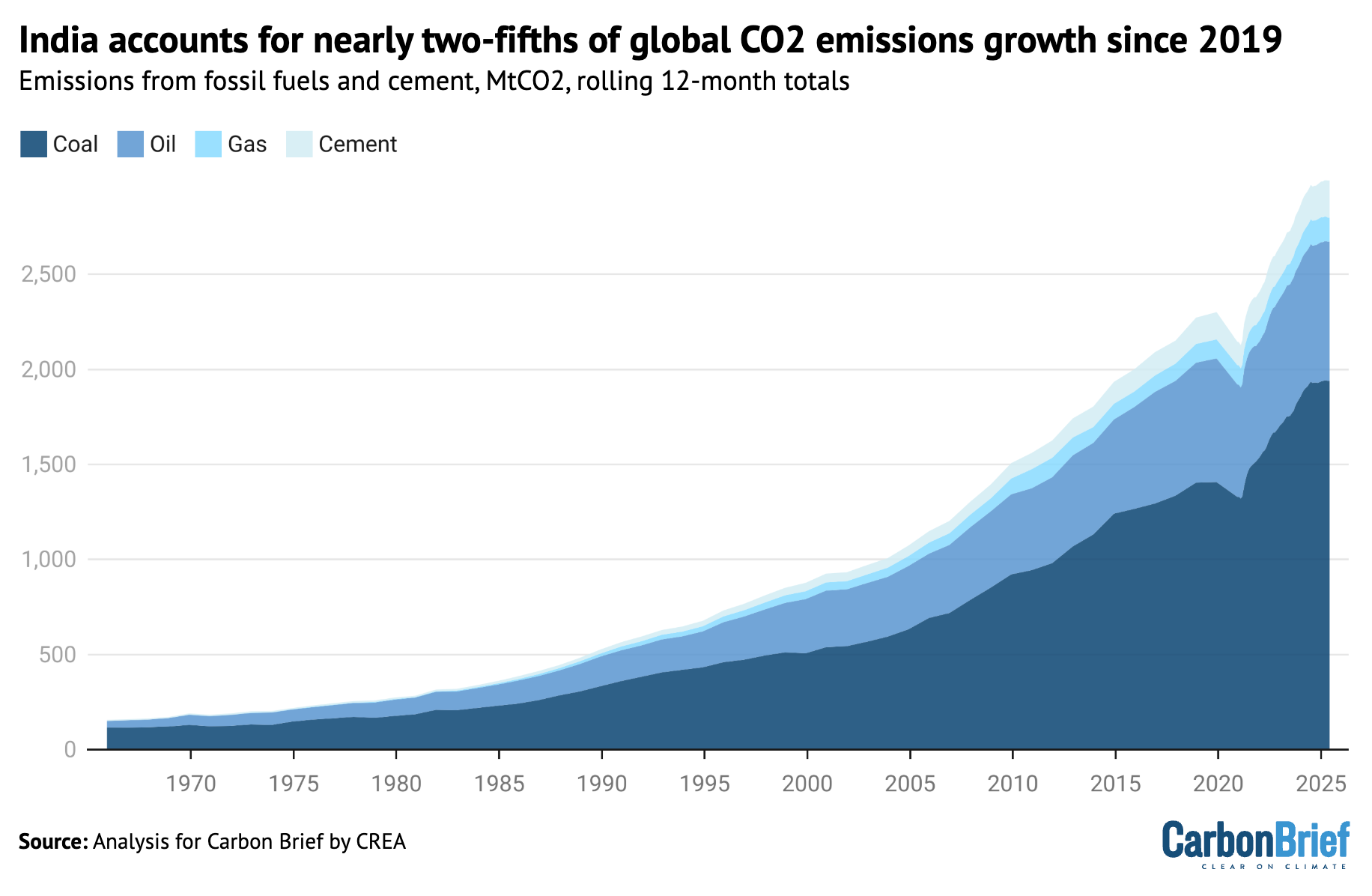

The future of CO2 emissions in India is a key indicator for the world, with the country – the world’s most populous – having contributed nearly two-fifths of the rise in global energy-sector emissions growth since 2019.

India’s surging emissions slow down

In 2024, India was responsible for 8% of global energy-sector CO2 emissions, despite being home to 18% of the world’s population, as its per-capita output is far below the world average.

However, emissions have been growing rapidly, as shown in the figure below.

The country contributed 31% of global energy-sector emissions growth in the decade to 2024, rising to 37% in the past five years, due to a surge in the three-year period from 2021-23.

More than half of India’s CO2 output comes from coal used for electricity and heat generation, making this sector the most important by far for the country’s emissions.

The second-largest sector is fossil fuel use in industry, which accounts for another quarter of the total, while oil use for transport makes up a further eighth of India’s emissions.

India’s CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and cement grew by 8% per year from 2019 to 2023, quickly rebounding from a 7% drop in 2020 due to Covid.

Before the Covid pandemic, emissions growth had averaged 4% per year from 2010 to 2019, but emissions in 2023 and 2024 rose above the pre-pandemic trendline.

This was despite a slower average GDP growth rate from 2019 to 2024 than in the preceding decade, indicating that the economy became more energy- and carbon-intensive. (For example, growth in steel and cement outpaced the overall rate of economic growth.)

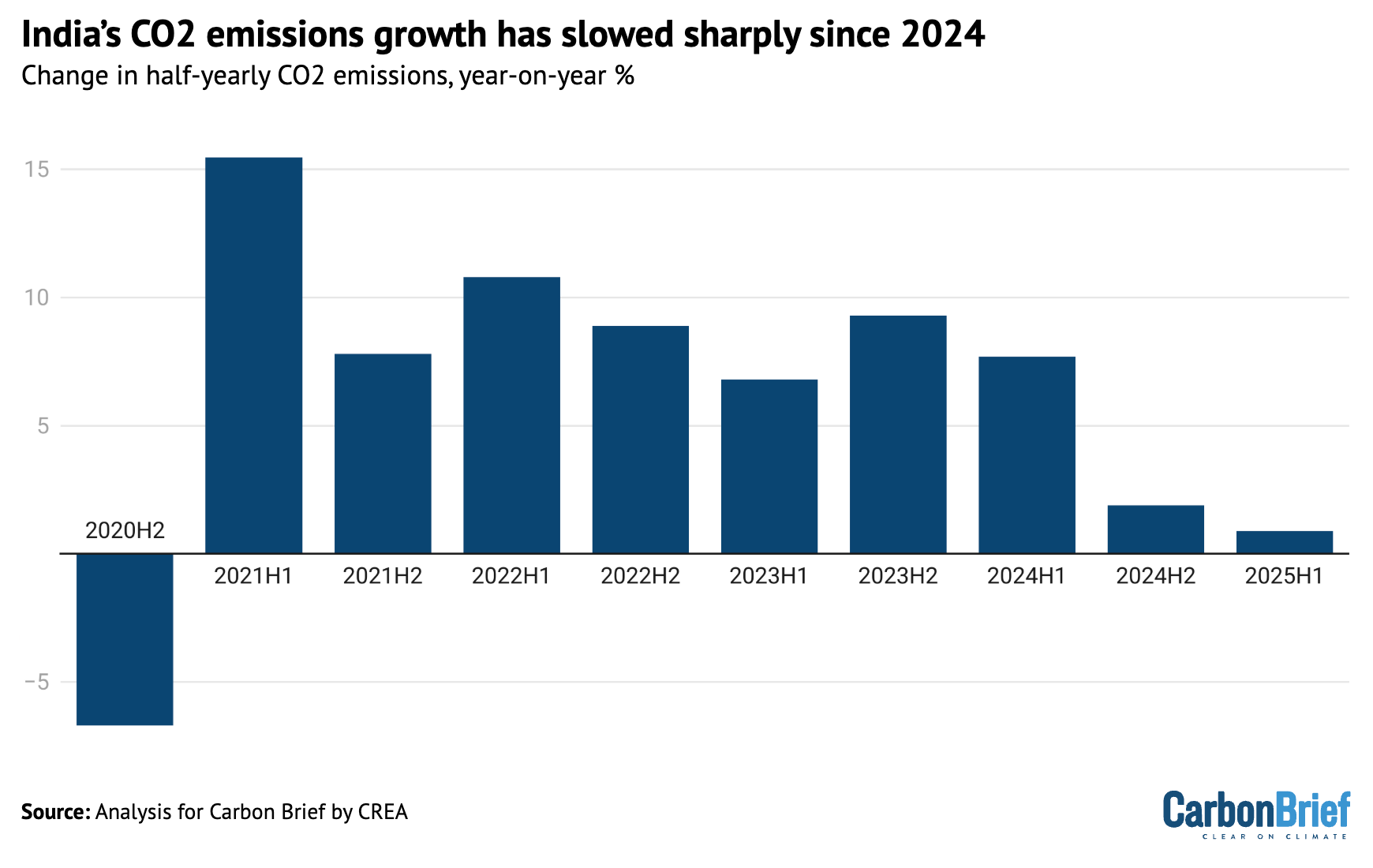

A turnaround came in the second half of 2024, when emissions only increased by 2% year-on-year, slowing down to 1% in the first half of 2025, as seen in the figure below.

The largest contributor to the slowdown was the power sector, which was responsible for 60% of the drop in emissions growth rates, when comparing the first half of 2025 with the years 2021-23.

Oil demand growth slowed sharply as well, contributing 20% of the slowdown. The only sectors to keep growing their emissions in the first half of 2025 were steel and cement production.

Another 20% of the slowdown was due to a reduction in coal and gas use outside the power, steel and cement sectors. This comprises construction, industries such as paper, fertilisers, chemicals, brick kilns and textiles, as well as residential and commercial cooking, heating and hot water.

This is all shown in the figure below, which compares year-on-year changes in emissions during the second half of 2024 and the first half of 2025, with the average for 2021-23.

Power sector emissions fell by 1% in the first half of 2025, after growing 10% per year during 2021-23 and adding more than 50m tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) to India’s total every six months.

Oil product use saw zero growth in the first half of 2025, after rising 6% per year in 2021-23.

In contrast, emissions from coal burning for cement and steel production rose by 10% and 7%, respectively, while coal use outside of these sectors fell 2%.

Gas consumption fell 7% year-on-year, with reductions across the power and industrial sectors as well as other users. This was a sharp reversal of the 5% average annual growth in 2021-23.

Power-sector emissions pause

The most striking shift in India’s sectoral emissions trends has come in the power sector, where coal consumption and CO2 emissions fell 0.2% in the 12 months to June and 1% in the first half of 2025, marking just the second drop in half a century, as shown in the figure below.

The reduction in coal use comes after more than a decade of break-neck growth, starting in the early 2010s and only interrupted by Covid in 2020. It also comes even as the country plans large amounts of new coal-fired generating capacity.

In the first half of 2025, total power generation increased by 9 terawatt hours (TWh) year-on-year, but fossil power generation fell by 29TWh, as output from solar grew 17TWh, from wind 9TWh, from hydropower by 9TWh and from nuclear by 3TWh.

Analysis of government data shows that 65% of the fall in fossil-fuel generation can be attributed to lower electricity demand growth, 20% to faster growth in non-hydro clean power and the remaining 15% to higher output at existing hydropower plants.

Slower growth in electricity usage was largely due to relatively mild temperatures and high rainfall, in contrast to the heatwaves of 2024. A slowdown in industrial sectors in the second quarter of the year also contributed.

In addition, increased rainfall drove the jump in hydropower generation. India received 42% above-normal rainfall from March to May 2025. (In early 2024, India’s hydro output had fallen steeply as a result of “erratic rainfall”.)

Lower temperatures and this abundant rainfall reduced the need for air conditioning, which is responsible for around 10% of the country’s total power demand. In the same period in 2024, demand surged due to record heatwaves and higher temperatures across the country.

The growth in clean-power generation was buoyed by the addition of a record 25.1GW of non-fossil capacity in the first half of 2025. This was a 69% increase compared with the previous period in 2024, which had also set a record.

Solar continues to dominate new installations, with 14.3GW of capacity added in the first half of the year coming from large scale solar projects and 3.2GW from solar rooftops.

Solar is also adding the majority of new clean-power output. Taking into account the average capacity factor of each technology, solar power delivered 62% of the additional annual generation, hydropower 16%, wind 13% and nuclear power 8%.

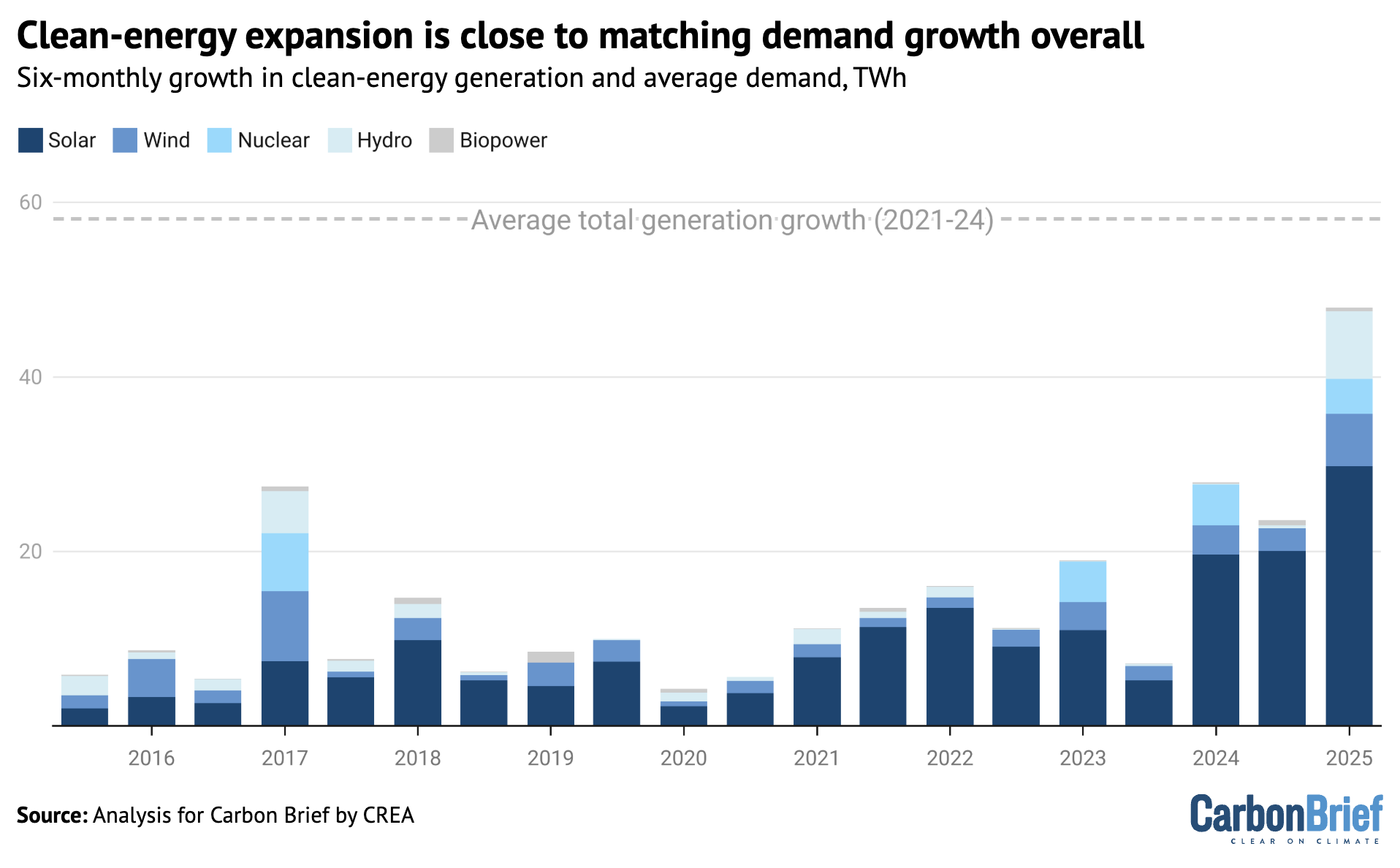

The new clean-energy capacity added in the first half of 2025 will generate record amounts of clean power. As shown in the figure below, the 50TWh per year from this new clean capacity is approaching the average growth of total power generation.

(When clean-energy growth exceeds total demand growth, generation from fossil fuels declines.)

India is expected to add another 16-17GW of solar and wind in the second half of 2025. Beyond this year, strong continued clean-energy growth is expected, towards India’s target for 500GW of non-fossil fuel capacity by 2030 (see below).

Slowing oil demand growth

The first half of 2025 also saw a significant slowdown in India’s oil demand growth. After rising by 6% a year in the three years to 2023, it slowed to 4% in 2024 and zero in the first half of 2025.

The slowdown in oil consumption overall was predominantly due to slower growth in demand for diesel and “other oil products”, which includes bitumen.

In the first quarter of 2025, diesel demand actually fell, due to a decline in industrial activity, limited weather-related mobility and – reportedly – higher uptake of vehicles that run on compressed natural gas (CNG), as well as electricity (EVs).

Diesel demand growth increased in March to May, but again declined in June because of early and unusually severe monsoon rains in India, leading to a slowdown in industrial and mining activities, disrupted supply-chains and transport of raw material, goods and services.

The severe rains also slowed down road construction activity, which in turn curtailed demand for transportation, construction equipment and bitumen.

Weaker diesel demand growth in 2024 had reflected slower growth in economic activity, as growth rates in the industrial and agricultural sectors contracted compared to previous years.

Another important trend is that EVs are also cutting into diesel demand in the commercial vehicles segment, although this is not yet a significant factor in the overall picture.

EV adoption is particularly notable in major metropolitan cities and other rapidly emerging urban centres and in the logistics sector, where they are being preferred for short haul rides over diesel vans or light commercial vehicles.

EVs accounted for only 7.6% of total vehicle sales in the financial year 2024-25, up 22.5% year-on-year, but still far from the target of 30% by 2030.

However, any significant drop in diesel demand will be a function of adoption of EV for long-haul trucks, which account for 32% of the total CO2 emissions from the transport sector. Only 280 electric trucks were sold in 2024, reported NITI Aayog.

Trucks remain the largest diesel consumers. Moreover, truck sales grew 9.2% year-on-year in the second quarter of 2025, driven in part by India’s target of 75% farm mechanisation by 2047. This sales growth may outweigh the reduction in diesel demand due to EVs. Subsidies for electric tractors have seen some pilots, but demand is yet to take off.

Apart from diesel, petrol demand growth continued in the first half of 2025 at the same rate as in earlier years. Modest year-on-year growth of 1.3% in passenger vehicle sales could temper future increases in petrol demand, however. This is a sharp decline from 7.5% and 10% growth rates in sales in the same period in 2024 and 2023.

Furthermore, EVs are proving to be cheaper to run than petrol for two- and three-wheelers, which may reduce the sale of petrol vehicles in cities that show policy support for EV adoption.

Steel and cement emissions continue to grow

As already noted, steel and cement were the only major sectors of India’s economy to see an increase in emissions growth in the first half of 2025.

While they were only responsible for around 12% of India’s total CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and cement in 2024, they have been growing quickly, averaging 6% a year for the past five years.

The growth in emissions accelerated in the first half of 2025, as cement output rose 10% and steel output 7%, far in excess of the growth in economic output overall.

Steel and cement growth accelerated further in July. A key demand driver is government infrastructure spending, which tripled from 2019 to 2024.

In the second quarter of 2025, the government’s capital expenditure increased 52% year-on-year. albeit from a low base during last year’s elections. This signals strong growth in infrastructure.

The government is targeting domestic steel manufacturing capacity of 300m tonnes (Mt) per year by 2030, from 200Mt currently, under the National Steel Policy 2017, supported by financial incentives for firms that meet production targets for high quality steel.

The government also imposed tariffs on steel imports in April and stricter quality standards for imports in June, in order to boost domestic production.

Government policies such as Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojna – a “housing for all” initiative under which 30m houses are to be built by FY30 – is further expected to lift demand for steel and cement.

The automotive sector in India is expected to grow at a fast pace, with sales expected to reach 7.5m units for passenger vehicle and commercial vehicle segments from 5.1m units in 2023, in addition to rapid growth in electric vehicles. This can be expected to be another key driver for growth of the steel sector, as 900 kg of steel is used per vehicle.

Without stringent energy efficiency measures and the adoption of cleaner fuel, the expected growth in steel and cement production could drive significant emissions growth from the sector.

Power-sector emissions could peak before 2030

Looking beyond this year, the analysis shows that CO2 from India’s power sector could peak before 2030, having previously been the main driver of emissions growth.

To date, India’s clean-energy additions have been lagging behind the growth in total electricity demand, meaning fossil-fuel demand and emissions from the sector have continued to rise.

However, this dynamic looks likely to change. In 2021, India set a target of having 500GW of non-fossil power generation capacity in place by 2030. Progress was slow at first, so meeting the target implies a substantial acceleration in clean-energy additions.

The country has been laying the groundwork for such an acceleration.

There was 234GW of renewable capacity in the pipeline as of April 2025, according to the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy. This includes 169GW already awarded contracts, of which 145GW is under construction, and an additional 65GW put out to tender. There is also 5.2GW of new nuclear capacity under construction.

If all of this is commissioned by 2030, then total non-fossil capacity would increase to 482GW, from 243GW at the end of June 2025, leaving a gap of just 18GW to be filled with new projects.

When the non-fossil capacity target was set in 2021, CREA assessed that the target would suffice to peak demand for coal in power generation before 2030. This assessment remains valid and is reinforced by the latest Central Electricity Authority (CEA) projection for the country’s “optimal power mix” in 2030, shown in the figure below.

In the CEA’s projection, the share of non-fossil power generation rises to 44% in the 2029-30 fiscal year, up from 25% in 2024-25. From 2025 to 2030, power demand growth, averaging 6% per year, is entirely covered from clean sources.

To accomplish this, the growth in non-fossil power generation would need to accelerate over time, meaning that towards the end of the decade, the growth in clean power supply would clearly outstrip demand growth overall – and so power generation from fossil fuels would fall.

While coal-power generation is expected to flatline, large amounts of new coal-power capacity is still being planned, because of the expected growth in peak electricity demand.

The post-Covid increase in electricity demand has given rise to a wave of new coal power plant proposals. Recent plans from the government target an increase in coal-power capacity by another 80-100GW by 2030-32, with 35GW already under construction as of July 2025.

The rationale for this is the increase in peak electricity loads, associated in particular with worsening heatwaves and growing use of air conditioning. The increase might yet prove unneeded.

Analysis by CREA shows that solar and wind are making an increasing contribution to meeting peak loads. This contribution will increase with the roll-out of solar power with integrated battery storage, the cost of which fell by 50-60% from 2023 to 2025.

The latest auction held in India saw solar power with battery storage bidding at prices, per unit of electricity generation, that were lower than the cost of new coal power.

This creates the opportunity to accelerate the decarbonisation of India’s power sector, by reducing the need for thermal power capacity.

The clean-energy buildout has made it possible for India to peak its power-sector emissions within the next few years, if contracted projects are built, clean-energy growth is maintained or accelerated beyond 2030 and demand growth remains within the government’s projections.

This would be a major turning point, as the power sector has been responsible for half of India’s recent emissions growth. In order to peak its emissions overall, however, India would still need to take further action to address CO2 from industry and transport.

With the end-of-September 2025 deadline nearing, India has yet to publish its international climate pledge (nationally determined contribution, NDC) for 2035 under the Paris Agreement, meaning its future emissions path, in the decades up to its 2070 net-zero goal, remains particularly uncertain.

The country is expected to easily surpass the headline climate target from its previous NDC, of cutting the emissions intensity of its economy to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030. As such, this goal is “unlikely to drive real world emission reductions”, according to Climate Action Tracker.

In July of this year, it met a 2030 target for 50% of installed power generating capacity to be from non-fossil sources, five years early.

About the data

This analysis is based on official monthly data for fuel consumption, industrial production and power generation from different ministries and government institutes.

Coal consumption in thermal power plants is taken from the monthly reports downloaded from the National Power Portal of the Ministry of Power. The data is compiled for the period January 2019 until June 2025. Power generation and capacity by technology and fuel on a monthly basis are sourced from the NITI data portal.

Coal use at steel and cement plants, as well as process emissions from cement production, are estimated using production indices from the Index of Eight Core Industries released monthly by the Office of Economic Adviser, assuming that changes in emissions follow production volumes.

These production indices were used to scale coal use by the sectors in 2022. To form a basis for using the indices, monthly coal consumption data for 2022 was constructed for the sectors using the annual total coal consumption reported in IEA World Energy Balances and monthly production data in a paper by Robbie Andrew, on monthly CO2 emission accounting for India.

Annual cement process emissions up to 2024 were also taken from Robbie Andrew’s work and scaled using the production indices. This approach better approximated changes in energy use and emissions reported in the IEA World Energy Balances, than did the amounts of coal reported to have been dispatched to the sectors, showing that production volumes are the dominant driver of short-term changes in emissions.

For other sectors, including aluminium, auto, chemical and petrochemical, paper and plywood, pharmaceutical, graphite electrode, sugar, textile, mining, traders and others, coal consumption is estimated based on data on despatch of domestic and imported coal to end users from statistical reports and monthly reports by the Ministry of Coal, as consumption data is not available.

The difference between consumption and dispatch is stock changes, which are estimated by assuming that the changes in coal inventories at end user facilities mirror those at coal mines, with end user inventories excluding power, steel and cement assumed to be 70% of those at coal mines, based on comparisons between our data and the IEA World Energy Balances.

Stock changes at mines are estimated as the difference between production at and despatch from coal mines, as reported by the Ministry of Coal.

In the case of the second quarter of the year 2025, data on domestic coal has been taken from the monthly reports by the Ministry of Coal. The regular data releases on coal imports have not taken place for the second quarter of 2025, for unknown reasons, so data was taken from commercial data providers Coal Hub and mjunction services ltd.

Product-wise petroleum product consumption data, as well as gas use by sector, was downloaded from the Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell of the Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas.

As the fuel dispatch and consumption data is reported as physical volumes, calorific values are taken from IEA’s World Energy Balance and CO2 emission factors from 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories.

Calorific values are assigned separately to different fuel types, including domestic and imported coal, anthracite and coke, as well as petrol, diesel and several other oil products.

The post Analysis: India’s power-sector CO2 falls for only second time in half a century appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: India’s power-sector CO2 falls for only second time in half a century

Greenhouse Gases

Chris Stark: The economics of clean energy ‘just get better and better’

The economics of clean energy “just get better and better”, leaving opponents of the transition looking like “King Canute”, says Chris Stark.

Stark is head of the UK government’s “mission” to deliver clean power by 2030, having previously been chief executive of the advisory Climate Change Committee (CCC).

In a wide-ranging interview with Carbon Brief, Stark makes the case for the “radical” clean-power mission, which he says will act as “huge insurance” against future gas-price spikes.

He pushes back on “super daft” calls to abandon the 2030 target, saying he has a “huge disagreement” on this with critics, such as the Tony Blair Institute.

Stark also takes issue with “completely…crazy” attacks on the UK’s Climate Change Act, warns of the “great risk” of Conservative proposals to scrap carbon pricing and stresses – in the face of threats from the climate-sceptic Reform party – the importance of being a country that respects legal contracts.

He says: “The problems and woes of this country, in terms of the cost of energy, are due to fossil fuels, not due to the Climate Change Act.”

The UK should become an “electrostate” built on clean-energy technologies, says Stark, but it needs a “cute” strategy on domestic supply chains and will have to interact with China.

Beyond the UK, despite media misinformation and the US turn against climate action, Stark concludes that the global energy transition is “heading in one direction”:

“You’ve got to see the movie, not the scene. The movie is that things are heading in one direction, towards something cleaner. Good luck if you think you can avoid that.”

- On the rationale for clean power 2030: “We’re trying to do something radical in a short space of time…It has all the characteristics of something that you can do quickly, but which has long-term benefit.”

- On grid investment: “[T]he programme of investment in infrastructure and in networks is genuinely once in a generation and we haven’t really done investment at this scale since the coal-fired generation was first planned.”

- On 88 “critical” grid upgrades: “We really need them to be on time, because the consumer will see the benefit of each one of those upgrades.”

- On electricity demand: “I think we are in the point now where we are starting to see the signal of that demand increase – and it is largely being driven by electric vehicle uptake.”

- On high electricity prices: “[I]t’s largely the product of decades of [decisions] before us. We do have high electricity prices and we absolutely need to bring them down.”

- On industrial power prices: “[W]e’ve got a whole package of things that…[will] take those energy prices down very significantly, probably below the sort of prices that you’ll see on the continent.”

- On cutting bills further: “The investments that we think we need for 2030…will add to some of those fixed costs, but…facilitate a lower wholesale price for electricity, [which] we think will at least match and probably outweigh those extra costs.”

- On insuring against the next gas price spike: “The amount of gas we’re displacing when that [new renewable capacity] comes online is a huge insurance [policy] against the next price spike that [there] will be, inevitably, [at] some point in the future for gas prices.”

- On Centrica boss Chris O’Shea’s comments on electricity bills in 2030: “I don’t think he’s right on this…I’m much more optimistic than Chris is about how quickly we can bring bills down.”

- On the need for investment: “I think there’s a hard truth to this, that any government – of any colour – would face the same challenge. You cannot have a system without that investment, unless you are dicing with a future where you’re not able to meet that future demand.”

- On the high price of gas power: “If you don’t think that offshore wind is the answer for [rising electricity demand], then you need to look to gas – and new gas is far more expensive.”

- On calls to scrap the 2030 mission: “I have a huge disagreement with the Tony Blair Institute on this…I think it’s daft – like, super daft – to step back from something that’s so clearly working.”

- On Conservative calls to scrap carbon pricing: “We absolutely have to have carbon pricing…if you want to make progress on our climate objectives. It also has been a very successful tool…I think it’s a great risk to start playing around with that system.”

- On gas prices being volatile: “[A]t the time that Russia invaded Ukraine…the global gas price spiked to an extraordinary degree…I’m afraid that is a pattern that is repeated consistently.”

- On insulating against gas price spikes: “[Y]ou cannot steer geopolitics from here in the UK. What you can do is insulate yourself from it…Clean power is largely about ensuring that.”

- On Reform threats to renewable contracts: “[A]ll this sort of threatening stuff, that is about ripping up existing contracts, has a much bigger impact than just the energy transition. This has always been a country that respects those legacy contracts.”

- On the wider benefits of the clean-power mission: “In the end, we’re bringing all sorts of benefits to the country that go beyond the climate here. The jobs that go with that transition, investment that comes with that and, of course, the energy security that we’re buying ourselves by having all of this domestic supply. It’s hard to argue that that is bad for the country.”

- On the UK’s plans for a renewable-led energy system: “[The] idea of a renewables-led system, with nuclear on the horizon, is just so clearly the obvious thing to do. I don’t really know what the alternative would be for us if we weren’t pursuing it.”

- On the UK becoming an “electrostate”: “Yes, that’s quite good for the climate…It’s also extraordinarily good for productivity, because you’re not wasting energy. Fossil fuels bring a huge amount of waste…You don’t get that with electrotech. I want us to be an electrostate.”

- On bringing supply chains and Chinese technology: “I want to see us adopt electrotech. I also want us to own a large part of the supply chain…I don’t think it’s ever going to be the case that we can…avoid the Chinese interaction…[B]ut I think it’s really important that our industrial strategy is cute about which bits of that supply chain it wants to see here.”

- On attacks on UK climate policy: “A lot of the criticism of the Climate Change Act I find completely…crazy. It has not acted as a straitjacket. It has not restricted economic growth. The problems and woes of this country, in terms of the cost of energy, are due to fossil fuels, not due to the Climate Change Act.”

- On media misinformation: “[C]limate change and probably net-zero have taken on a role in the ‘culture wars’ that they didn’t previously have.”

- On winning the argument for clean power: “Actually, it’s not to shoot down every assertion that you know to be false. It’s just to get on with trying to do this thing, to demonstrate to people that there’s a better way to go about this.”

- On net-zero: “I think we are getting beyond a period where net-zero has a slogan value. I think it’s probably moved back to being what it always should have been, really, which is a scientific target – and in this country, a statutory target that guides activity.”

- On the geopolitics of climate action: “[I]t’s striking how much it’s shifted, not least because of the US…It is slightly weird…that has happened at a time when every day, almost, the evidence is there that the cleaner alternative is the way that the world is heading.”

- On US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement: “I wish that hadn’t happened, but the economics of the cleaner alternative that we’re building just get better and better over time.”

- On watching “the movie, not the scene”: “The movie is that things are heading in one direction, towards something cleaner. Good luck if you think you can avoid that – [like] King Canute.”

Carbon Brief: Thanks very much for joining us today. Chris, you’re in charge of the government’s mission for clean power by 2030. Can you just explain what the point of that mission is?

Chris Stark: Well, we’re trying to do something radical in a short space of time. And maybe if I start with the backstory to that, Ed Miliband, as secretary of state, was looking for a project where he could make a difference quickly. And the reason that we are focused on clean power 2030 is because it is that project. It has all the characteristics of something that you can do quickly, but which has long-term benefits.

What we’re trying to do is to accelerate a process that was already underway of decarbonising the power system, but to do so in a time when we feel it’s essential that we start that journey and move it more quickly, because in the 2030s we’re expecting the demand for electricity to grow. So this is a bit of a sprint to get ourselves prepped for where we think we need to be from 2030 onwards. And it’s also, coming to my role, it’s the job I want to do, because I spent many years advising that you should decarbonise the economy by electrifying – and stage one of that is to finish the job on cleaning up the supply.

So it’s kind of the perfect project, really. And if you want to do clean power by 2030, [the] first thing is to say we’re not going to take an overly purist approach to that. So we admit and are conscious – in fact, find it useful – to have gas in the mix between now and 2030. The challenge is to run it down to, if we can, 5% of the total mix in 2030 and to grow the clean stuff alongside it. So, using gas as a flexible source, and that, we think is a great platform to grow the demand for electricity on the journey, but especially after 2030 – and that’s when the decarbonisation really kicks in.

So it’s a sort of exciting thing to try and do. And if you want to do it, here comes the interesting thing. You need the whole system, all the policies, all the institutions, all the interactions with the private sector, interactions with the consumer, to be lined up in the right way.

So clean power by 2030 is also the best expression of how quickly we want the planning system to work, how much harder we want the energy institutions like NESO [the National Energy System Operator] and energy regulator Ofgem to support it – and how we want to send a message to investors that they should come here to do their investment. Turns out, it’s a great way of advertising all of that and making it happen. And so far, it’s working great.

CB: Thanks. So do you still think it’s achievable? We’re sitting in “mission control”. You’ve got some big screens on the wall. Is there anything on those screens that’s flashing red at the moment?

CS: So, right behind you are the big screens. And it’s tremendously useful to have a room, a physical space, where we can plan this stuff and coordinate this stuff. There’s lots of things that flash red. There’s no question. And it’s an expression of it being a genuine mission. This is not business as usual. So you wouldn’t move as quickly as this, unless you’ve set your North Star around it. And it does frame all the things that, especially this department is doing, but also the rest of government, in terms of the story of where we are.

We’re approaching two years into this mission and – really important to say – if the mission is about constructing infrastructure, it’s in that timeframe that you’ll do most of the work, setting it up so that we get the things that we think we need for 2030 constructed.

We’re already reaching the end of that phase one, and we did that by first of all, going as hard and as fast as we could to establish a plan for 2030, which involved us going first to the energy system operator, NESO, to give us their independent advice. We then turned that into a plan, and the expression of that plan is largely that we need to see construction of new networks, new generation, new storage and a new set of retail models to make all of that stick together well for the consumer.

Phase one was about using that plan to try and go hard at a set of super-ambitious technology ranges for all the clean technologies, so onshore wind, offshore wind, solar [and] also the energy storage technologies. We’ve set a range that we’re trying to hit by 2030 that is right at the top end of what we think is possible. Then we went about constructing the policies to make that happen.

Behind you on the big screens, what we’re often doing is looking at the project pipeline that would deliver that [ambition]. At the heart of it is the idea that if you want to do something quickly by 2030, there is a project pipeline already in development that will deliver that for you, if you can curate it and reorder it to deliver. And therefore, the most important and radical thing that we did – alongside all the reforms to things like contracts for difference and the kind of classic policy support – is this very radical reordering of the connection queue, which allows us to put to the front of the queue the projects that we think will deliver what we need for 2030 – and into the 2030s.

Then, alongside that, the other big thing, and I think this is going to be more of a priority in the second phase of work for us, is the networks themselves. We are trying to essentially build the plane while it flies by contracting the generation whilst also building the networks, and of course, doing this connection queue reform at the same time. That is, again, radical, but the programme of investment in infrastructure and in networks is genuinely once in a generation and we haven’t really done investment at this scale since the coal-fired generation was first planned. We think a lot about 88 – we think – really critical transmission upgrades. We really need them to be on time, because the consumer will see the benefit of each one of those upgrades.

CB: You already talked about electricity demand growing as the economy electrifies. Do you think that there’s a risk that we could hit the clean power 2030 target, but at the same time, perhaps meeting it accidentally, by not electrifying as quickly as we think – and therefore demand not growing as quickly?

CS: So, an unspoken – we need to clearly make this more of a factor – an unspoken factor in the shape of the energy system we have today has been an assumption, for well over 20 years, really, that demand for electricity was always going to pick up. In fact, what we’ve seen is the opposite. So for about a quarter of a century, demand has fallen. Interestingly, the system – the energy system, the electricity system – generally plans for an increase in demand that never arrives. We could have a much longer conversation about why that happened and the institutional framework that led to that. But it is nonetheless the case.

I think we are at the point now where we are starting to see the signal of that demand increase – and it is largely being driven by electric vehicle uptake. The story of net-zero and decarbonisation does rest on electrification at a much bigger scale than just electric cars. So part of what we’re trying to do is prepare for that moment.

But you’re absolutely right, if demand doesn’t increase, the biggest single challenge will be that we’ve got a lot of new fixed costs and a bigger system – on the generation side and the network side – that are being spread over a demand base that’s too small. So, slightly counter-intuitively, because there’s a lot of coverage around the world about the concern about the increase in electricity demand, I want that increase in electricity demand, but I also want it to be of a particular type. So if we can, we want to grow the demand for electricity with flexible demand, as much as possible, that is matching – as best we can – the availability of the supply when the wind blows or the sun shines. That makes the system itself cheaper.

The more electricity demand we see, the more those fixed costs that are in the system – for networks and increasingly for the large renewable projects – the more they are spread over a bigger demand base and the lower the unit costs of electricity, which will be good, in turn, for the uptake of more and more electrification in the future. So there’s this virtuous circle that comes from getting this right. In terms of where we go next with clean power 2030, a big part of that story needs to be electrification. We want to see more electricity demand, again, of the right sort, if we can. More flexible demand and, again, [the] more that that is on the system, the better the system will operate – and the cheaper it will be for the consumer.

CB: So, the UK has among the highest electricity prices of any major economy. Can you just talk through why you think that is – and what we should be doing about it?

CS: Yeah, there’s a story that the Financial Times runs every three months about the cost of electricity – and particularly industrial electricity prices. Every time that happens, we slightly wince here, because it’s largely the product of decades of [decisions] before us.

We do have high electricity prices and we absolutely need to bring them down. For those industrial users, we’ve got a whole package of things that will come on, over the next few months, into next year, that will make a big difference, I think. For those industrial users, [it will] take those energy prices down very significantly, probably below the sort of prices that you’ll see on the continent, and that, I hope, will help.

But we have a bigger plan to try and do something about electricity prices for all consumers. I think it’s worth just dwelling on this: two-thirds of electricity consumption is not households, it’s commercial. So the biggest part of this is the commercial electricity story – and then the rest, the final third, is for households. The politics of this, obviously, is around households.

You’ve seen in the last six months, this government has focused really hard on the cost of living and one of the best tools – if you want to go hard at it, to improve the cost of living – is energy bills. So the budget last year was a really big thing for us. It involved months of work – actually in this room. We commandeered this room to look solely at packages of policy that would reduce household bills quickly and landed on a package that was announced in the budget last year, that will take £150 off household bills from April. That’s tremendous – and it’s the sort of thing that we were advising when I was in the Climate Change Committee – because the core of that is to take policy costs off electricity bills, particularly, and to put them into general taxation, where [you have] slightly more progressive recovery of those costs.

But there’s not another one of those enormous packages still to come. What we’re dealing with, to answer your question, is a set of system costs, as we think of them, that are out there and must be recovered. Now we’ve chosen, in the first instance, to move some of those costs into general taxation. The next phase of this involves us doing the investments that we think we need for 2030, which will add to some of those fixed costs, but doing so because we are going to facilitate a lower wholesale price for electricity, that we think will at least match and probably outweigh those extra costs.

That opens up a further thing, which I think is where we’ll go next with this story, on the consumer side, which is that we want to give the opportunity to more consumers – be they commercial or household – to flexibly use that power when it’s available, and to do so in a way that makes that power cheaper for them.

You most obviously see that in something we published just a few weeks ago, the “warm homes plan”, which, in its DNA, is about giving packages of these technologies to those households that most need them. So solar panels, batteries and eventually heat pumps in the homes that are most requiring of that kind of support, to allow them to access the cheaper energy that’s been available for a while, actually, if you’re rich enough to have those technologies already. That notion of a more flexible tech-enabled future, which gives you access to cheaper electricity, is where I think you will see the further savings that come beyond that £150. So the £150 is a bit like a down payment on all of that, but there’s still a lot more to come on that. And in a sense, it’s enabled by the clean power mission.

You know, we are moving so quickly on this now and maybe the final thing to say is that as we bring more and more renewables under long-term contracts – hopefully at really good value, discovered through an auction – we will be displacing more and more gas. If you look back over the last two auctions, it’s quite staggering, 24 gigawatts [GW] – I think it is maybe more than that – we’ve contracted through two auction rounds. The amount of gas we’re displacing when that stuff comes online is a huge insurance [policy] against the next price spike that [there] will be, inevitably, [at] some point in the future for gas prices. There’s usually one or two of these price spikes every decade. So, when that moment comes, we’re going to be much better insulated from it, because of these – I think – really good-value contracts that we’re signing for renewables.

CB: We’ve seen quite a few public interventions by energy bosses recently – just this week, Chris O’Shea at Centrica, saying that electricity prices by 2030 could be as high as they were in the wake of Russia invading Ukraine. Just as a reminder, at that point, we were paying more than twice as much per unit of electricity as we’re paying now – or we would have been if the government hadn’t stepped in with tens of billions in subsidies. Can I just get your response to those comments from Chris O’Shea?

CS: Well, listen, Chris and I know each other well. In fact, he’s a Celtic fan, he lives around the corner from me in Glasgow and he comes up for Celtic games regularly. So I do occasionally speak to him about these things. I don’t think he’s right on this. To put it as simply as I can, our view is very definitely that as we bring on the projects that we’re contracting in AR6 [auction round six], AR7 and into AR8 and 9, as those projects are connected and start generating, we are going to see lower prices. That doesn’t mean that we’re complacent about this, but we’ve got, I would say, a really well-grounded view of how that would play out over the next few years. And you know, £150 off bills next year is only part one of that story. So I’m much more optimistic than Chris is about how quickly we can bring bills down.

CB: This government was obviously elected on a pledge to cut bills by £300 from 2024 to 2030. Do you think that’s achievable? You talked about £150 pounds. That’s half…

CS: Well if Ed [Miliband, energy secretary] were here, he would remind you it was up to £300. And of course, that matters. But yes, I do think – of course – I think that’s well in scope. I don’t want to gloss over this, though; there are real challenges here. We are entering a period where there’s a lot of investment needed in our energy system and our power system.

I think there’s a hard truth to this, that any government – of any colour – would face the same challenge. You cannot have a system without that investment, unless you are dicing with a future where you’re not able to meet that future demand that we keep referring to. So I think we’re doing a really prudent thing, which is approaching that investment challenge in the right way, to spread the costs in the right way for the consumer – so they don’t see those impacts immediately – and to get us to the to the situation where we’re able to sustain and meet the future demands that this country will have, in common with any other country in the world as it starts to electrify at scale. That’s what we should be talking about.

We have really tried to push that argument, particularly with the offshore wind results, where we were making the counter case, that if you don’t think that offshore wind is the answer for this, then you need to look to gas – and new gas is far more expensive. In a world where you’re having to grow the size of the overall power system, I think it’s very prudent to do what we’re doing. So the network costs, the renewables costs that are coming, these are all part of the story of us getting prepared for the system that we need in the future, at the best possible price for the consumer. But of course, we would like to see a quicker impact here. We’d like to see those bills fall more quickly and I think we still have a few more tools in the box to play.

CB: There’s an argument around that the clean power mission is, in fact, part of the problem, or even the biggest problem, in driving high bills. Do you think that getting rid of the mission would help to cut bills, as the Tony Blair Institute’s been suggesting?

CS: I have a huge disagreement with the Tony Blair Institute on this. I mean, step back from this. The word mission gets bandied around a lot and I am very pleased that this mission continues. Mission government is quite a difficult thing to do and we’re definitely delivering against the objectives that we set ourselves. But it’s interesting just to step back and understand why that’s happening. We deliberately aimed high with this mission because if you are mission-driven, that’s what you should do. You should pitch your ambitions to…the top of where you think you can reach, in the knowledge that you shouldn’t do that at any price. We’ve made that super clear, consistently. This is not clean power at any price. But also in the knowledge that if you aim your ambitions high, in a world where actually most of the work is done by the private sector, they need to see that you mean it – and we mean it.

There’s a feedback loop here that, the more that the industry that does the investment and puts these projects in the ground, the more that they see we mean it, the more confident they are to do the projects, the more we can push them to go even faster. And Ed, in particular, has really stuck to his guns on this, because his view is, the minute you soften that message, the more likely it is [that] the whole thing fails.

So occasionally, you know – our expression of clean power is 95% clean in the year 2030 – occasionally you get people, particularly in the energy industry itself, say, “wow, you know, maybe it’d be better if you said 85%”. The reality is, if you said 85%, you wouldn’t get 85%, you would get 80%, so there’s a need to keep pushing the envelope here, because if we all stick to our guns, we’ll get to where we need to get to.

And that message on price, I have to say that was one of the best things last year, is that Ed Miliband made a really important speech at the Energy UK conference, to say to the industry, we will support offshore wind, but only if it shows the value that we think it needs to show for the consumer. And the industry stepped up and delivered on that. So that’s part of the mission. So that’s a very long way of saying I think it’s daft – like, super daft – to step back from something that’s so clearly working now.

CB: The Conservatives, in opposition, are claiming that we could cut bills by getting rid of carbon pricing and not contracting for any more renewables. They say getting rid of carbon pricing would make gas power cheap. What’s your view on their proposals and what impact would it have if they were followed through?

CS: Well, look, carbon pricing has a much bigger role to play. We absolutely have to have carbon pricing in the system and in this economy, if you want to make progress on our climate objectives. It also has been a very successful tool, actually sending the right message to the industry to invest in the alternatives – the low-carbon alternatives – and that is one of the reasons why this country is doing very well, actually, cleaning up the supply of electricity – quite remarkably so actually, we really stand out. I think it’s a great risk to start playing around with that system.

My main concern, though, is that the interaction with our friends on the continent [in the EU] does depend on us having carbon pricing in place. A lot of the stuff that I read – and not particularly talking about the Conservative proposals here at all, actually – but some of the commentary on this imagines a world where we are acting in isolation. Actually, we need to remember that Europe is erecting – and has erected now – a carbon border around it. Anything that we try to export to that territory, if it doesn’t have appropriate carbon pricing around it, will simply be taxed.

I think we need to remember that we’re in an interconnected world and that carbon pricing is part of that story. In the end, we won’t have a problem if we remove the fossil [fuel] from the system in the first place, that’s causing those costs. I think we’re following the right track on this. In a sense, my strategy isn’t to worry so much about the carbon pricing bit of it. It’s to displace the dirty stuff with clean stuff. That strategy, in the end, is the most effective one of all. It doesn’t matter what the ETS [emissions trading system] is telling you in terms of carbon pricing or what the carbon price floor is, we won’t have to worry at all about that if we have more and more of this clean stuff on the system.

CB: Just in terms of that idea that gas is actually really cheap, if only we could ignore carbon pricing. What do you think about that?

CS: Well, gas prices fluctuate enormously. The stat I always return to, or the fact that was returned to, is that we had single-digits percentage of Russian gas in the British system at the time that Russia invaded Ukraine, but we faced 100% of the impact that that had on the global gas price – and the global gas price spiked to an extraordinary degree after that. I’m afraid that is a pattern that is repeated consistently.

We’ve had oil crises in the past and we’ve had gas crises – and every time we are burned by it. The best possible insulation and insurance from that is to not have that problem in the first place. What we are about is ensuring that when that situation – I say when – that situation arises again, who knows what will drive it in the future? But you cannot steer geopolitics from here in the UK. What you can do is insulate yourself from it the next time it happens.

Clean power is largely about ensuring that in the future, the power price is not going to be so impacted by that spike in prices. Sure, there’s lots of things you could do to make it [electricity] cheaper, but these are pretty marginal things, in terms of the overall mission of getting gas out of the system in the first place.

CB: Another opposition party, Reform, thinks that net-zero is the whole problem with high electricity prices. They’re pledging to, if they get into government, to rip up existing contracts with renewables. To what extent do you think the work that you’re doing now in mission control is locking in progress that will be very difficult to unpick?

CS: Well, it’s important to say that we do not start from the position that we’re trying to lock in something that a future government would find difficult to unwind. I mean, this is just straightforwardly an infrastructure challenge, in terms of what…we would like to see built and need to see built. And yes, I think it will be difficult to unwind that, because these are projects we want to actually have in construction.

We don’t want to find ourselves – ever – in the future, in the kind of circumstance that you might see in the US, where projects are being cancelled so late that actually they end up in the courts. So look, it’s not my job to advise the Reform Party and what their policy is on this. But all I would say is that all this sort of threatening stuff, that is about ripping up existing contracts, has a much bigger impact than just the energy transition. This has always been a country that respects those legacy contracts. I’m happy that it would be very difficult to change those contracts, because we [the government] are not a counterparty to those contracts. The Low Carbon Contracts Company was set up for this purpose. These are private-law contracts between developers and the LCCC. It would be extraordinarily difficult to step into that – you probably would need to take extraordinary measures to do so – and to what end?

I suppose my objective is simply to get stuff built and, in so doing, to demonstrate the value of those things, even if you don’t care about climate change. In the end, we’re bringing all sorts of benefits to the country that go beyond the climate here. The jobs that go with that transition, [the] investment that comes with that and, of course, the energy security that we’re buying ourselves by having all of this domestic supply. It’s hard to argue that that is bad for the country. It seems to me that that, inevitably, will mean that we will lock in those benefits into the future, with the clean power mission.

CB: One of the things that’s been happening in the last few years is that solar continues this kind of onward march of getting cheaper and cheaper over time, but things like offshore wind, in particular – but arguably also gas power [and] other forms of generation – have been getting more expensive, due to supply chain challenges and so on. Do you think that means the UK has taken the wrong bet by putting offshore wind at the heart of its plans?

CS: I mean, latitude matters. It is definitely true that, were we in the sun-belt latitude of the world, solar would be the thing that we’d be pursuing. But we are blessed in having high wind speeds, relatively shallow waters and a pretty important requirement for extra energy when it’s cold over the winter. And all that stuff coincides quite nicely with wind – and in particular, offshore wind. So I think our competitive advantage is to develop that. There are plenty of places, particularly in the northern hemisphere, [but] also potentially places like Japan down in Asia, where wind will be competitive.

The long future of this is, I tend to think, in terms of where we’re heading, we are going to head eventually – ultimately – to a world where the wholesale price of this stuff is going to be negligible, whether it’s solar or wind. Actually, the competitive challenge of it being slightly more expensive to have wind rather than solar is not going to be a major factor for us. But we can’t move the position of this country – and therefore we should exploit the resources that we have. I think it’s also true that there’s room in the mix for more nuclear – and yes, we have solar capacity, particularly in the south of the country, that we want to see exploited as well.

Bring it all together, that idea of a renewables-led system, with nuclear on the horizon, is just so clearly the obvious thing to do. I don’t really know what the alternative would be for us if we weren’t pursuing it. It’s a very obvious thing to do. Solar has this astonishing collapse in price over time. We’re in a period, actually, where [solar’s] going slightly more expensive at the moment because some of the components, like silver, for example, are becoming more expensive. So, a few blips on the way, but the long-term journey is still that it will continue to fall in price.

We want to get wind back on that track. The only way that happens and the only way that we get back on the cost-saving trajectory is by continuing to deploy and seeing deployment in other territories as well. We are a big part of that story. The big auction that we had recently for offshore wind [was a] huge success for us, that’s been noticed in other parts of the world. We had the North Sea summit, for example, in Hamburg.

Just a few weeks ago, we were the talk of the town, because we have, I think, righted the ship on the story of offshore wind. That’s going to give investors confidence. Hopefully, we can get those technologies back on a downward cost curve again and allow into the mix some of the more nascent technologies there, particularly floating offshore wind. We’ve got a big role to do some of that, but it’s all good for this country and any other country that finds itself in a similar latitude.

CB: The UK strategy is – you mentioned this already – it’s increasingly all about electrification. Electrotech, as it’s being called, solar, batteries, EVs, renewables. Do you think that that is genuinely a recipe for energy security, or are we simply trading reliance on imported fossil fuels for reliance on imports that are linked to China?

CS: So there’s a lot in that question. I mean, the first thing to say, I’ve been one of the people that’s been talking about electrostates. Colleagues use the term electrotech interchangeably, essentially, but the electrostates idea is basically about two things. These are the countries of the world that are deploying renewables, because they are cheap, and then deploying electrified technologies that use the renewable power, especially using it flexibly when it’s available. The combination of those two things is what makes an electrostate.

Yes, that’s quite good for the climate – and that’s obviously where I’ve been most interested in it. It’s also extraordinarily good for productivity, because you’re not wasting energy. Fossil fuels bring a huge amount of waste – almost two-thirds, perhaps, of fossil-fuel energy is wasted through the lost heat that comes from burning it. You don’t get that with electrotech. So there’s lots of good, solid productivity and efficiency reasons to want to have an electrostate and a system that is based – an economy that’s based – more on electrotech.

You’ve come now to the most interesting thing, which is inherent in your question, which is, are we trading a dependency on increasingly imported fossil fuels for a dependency on imported tech? And I do think that is something that we should think about. I think underneath that, there are other issues playing out, like, for example, the mineral supply chains that sit in those technologies.

I think we in this country need to accept that some of that will be imported, but we should think very carefully about which bits of that supply chain we want to host and really go at that, as part of this story. So I want us to be an electrostate. I want to see us adopt electrotech. I also want us to own a large part of the supply chain.

Now, offshore wind is an obvious example of that. So we would like to see the blade manufacturing happening here, but also the nacelles and the towers. It’s perfectly legitimate for us to go for that. That’s the story of our ports and our manufacturing facilities. I think it is also true that we should try and bring battery manufacturing to the UK. It’s a sensible thing to have production of batteries in this territory. Yes, we wouldn’t sew up the entire supply chain, but that is something we should be going for.

Then there are other bits to this, including things like control systems and the components that are needed in the power system, where we have real assets and strength, and we want to have those bits of the supply chain here too. So, you know, we’re in a globalised world. I don’t think it’s ever going to be the case that we can, for example, avoid the Chinese interaction. I don’t think that should be our objective at all, but I think it’s really important that our industrial strategy is cute about which bits of that supply chain it wants to see here and that is what you see in our industrial strategy.

So as we get into the next phase of the clean power mission, electrification and the industrial strategy that sits alongside that, I think, probably takes on more and more importance.

CB: I want to pan out a little bit now and you obviously were very focused, in your previous role, on the Climate Change Act. There’s been quite a lot of suggestions – particularly from some opposition politicians – that the Climate Change Act has become a bit of a straitjacket for policymaking. Do you think that there’s any truth in that and is it time for a different approach?

CS: We should always remember what the Climate Change Act is for. It was passed in 2008. It was not, I think, intended to be this sort of originator of the government’s economic plans. It is there to act as a sort of guardrail, within which governments of any colour should make their plans for the economy and for broader society and for industry and for the energy sector and every other sector within it. I think to date, it’s done an extraordinarily good job of that. It points you towards a future. A lot of the criticism of the Climate Change Act, I find completely…crazy. It has not acted as a straitjacket. It has not restricted economic growth. The problems and woes of this country, in terms of the cost of energy, are due to fossil fuels, not due to the Climate Change Act.

But I think it is also true to say that as we get further along the emissions trajectory that we need to follow in the Climate Change Act, it clearly gets harder. And you know, the Act was designed to guide that too. So what it’s saying to us now is that you have to make the preparations for the tougher emissions targets that are coming, and that is largely about getting the infrastructure in place that will guide us to that. If you do that now, it’s actually quite an easy glide path into carbon budgets five and six and seven. If you don’t, it gets harder, and you then need to look to some more exotic stuff to believe that you’re going to hit those targets.

I think we’ve got plenty of scope for the Climate Change Act still to play the role of providing the guardrails, but it doesn’t need to define this government’s industrial policy or economic policy – and neither does it. It should shape it – and I think the other thing to say about the Climate Change Act is it has definitely shown its worth on the international stage. It brings us – obviously – influence in the climate debate. But it has also kept us on the straight and narrow in a host of other areas too, not least the energy sector.

We have shown how it is possible to direct decarbonisation of energy, while seeing the benefits of all that and jobs that go with it, and investment that comes with it, probably more so than any other country, actually. So a Western democracy that’s really going to follow the rules has seen the benefits from it. I want to see that kind of strategy, of course, in the power sector, but I want to see us direct that towards transport, towards buildings and especially towards the industries that we have here. Reshoring industries, because we are a place that’s got this cheap, clean energy, is absolutely the endpoint for all of this.

So I’m not worried about the Climate Change Act, as long as we follow the implications of what it’s there for. You know, we’ve got to get our house in order now and get those infrastructure investments in place and in the spending review just last year, you could see the provision that was made for that – Ed Miliband [was] extraordinarily successful in securing the deal that he needed. This year, of course, we will have to see the next carbon budget legislated. That’s a lot easier when you’ve got plans that point us in the right direction towards those budgets.

CB: I wanted to ask about misinformation, which seems to be an increasingly big feature of the media and social-media environment. Do you think that’s a particular problem for climate change? Any reflections on what’s been happening?

CS: I suppose I don’t know if it’s a particular problem for climate change, but I know that it is a problem for climate change. There may well be similar campaigns and misinformation on other topics. I’m not so familiar with them. But it’s a huge frustration that it’s become as prevalent and as obvious as it is now. I mean, I used to love Twitter. You and I would interact on Twitter. I would interact with other commentators on Twitter and interact with real people on Twitter…But that’s one of the great shames, is that platform has been lost to me now – and one of the reasons for that is it’s been engulfed by this misinformation. It is very difficult to see a way back from that.

Actually, I don’t know quite what leads it to be such a big issue, but I think you have to acknowledge that climate change and probably net-zero have taken on a role in the “culture wars” that they didn’t previously have, or if they did, it wasn’t as prevalent as it is now. That is what feeds a lot of this stuff. It’s quite interesting doing a job like this now [within government], because when we were at the Climate Change Committee, I felt this stuff more acutely. It was quite raw. If someone made a real, you know, crazy assertion about something. Here – maybe it’s the size of the machine around government – it causes you to be slightly more insulated from it.

It’s been good for me, actually, to do that, because it means you just get your head down and get on with it, because you know, at the end of it, you’re doing the right thing. I think in the end, that’s how you win the arguments. Actually, it’s not to shoot down every assertion that you know to be false. It’s just to get on with trying to do this thing, to demonstrate to people that there’s a better way to go about this. That is largely what we’ve been trying to do with the clean-power mission, is try not to be too buffeted by that stuff, but actually spend, especially the last two years – it’s hard graft right – putting in place the right conditions. Hopefully now, we’re in a period where you’re going to start to see the benefits of that.

CB: Final question before you go. Just stepping back to the big picture, how optimistic do you feel – in this world of geopolitical uncertainty – about the UK’s net-zero target and global efforts to avoid dangerous climate change?

CS: I’m going to be very honest with you, it’s been tough, right? There was a different period in the discussion of climate when I was very fortunate to be at the Climate Change Committee and there was huge interest globally – and especially in the UK – on more ambition. It did feel that we were really motoring over that period. Some of the things that have happened in the last few years have been hard to swallow.

[It’s] quite interesting doing what I do now, though, in a government that has stayed committed to what needs to be done in the face of a lot of things – and in particular the Clean Power mission, which has acted as sort of North Star for a lot of this. It’s great – you see the benefit of not overreacting to some of that shift in opinion around you, [which] is that you can really get on with something.

We talked earlier about the industry reaction to what we’re trying to do on clean power. You do see this virtuous circle of government staying close to its commitments and the private sector responding and a good consumer impact, if you collectively do that well. I think the net-zero target implies doing more of that. Yes, in the energy system, but also in the transport system and in the agriculture system and in the built environment. There’s so much more of this still to come.

The net-zero target itself, I think, we are getting beyond a period where net-zero has a slogan value. I think it’s probably moved back to being what it always should have been, really, which is a scientific target – and in this country, a statutory target that guides activity.

But I don’t want to gloss over the geopolitical stuff, because it’s striking how much it’s shifted, not least because of the US and its attitudes towards climate. It is slightly weird then to say that, well, that has happened at a time when every day, almost, the evidence is there that the cleaner alternative is the way that the world is heading.

As we talk today, there’s the emission stats from China, which do seem to indicate that we’re getting close to two years of falls in carbon dioxide emissions from China. That’s happening at a time when their energy demand is increasing and their economy is growing. That points to a change, that we are seeing now the impact of these cleaner technologies [being] rolled out. So I suppose, in that world, that’s what I go back to, in a world where the discussion of climate change is definitely harder right now – no doubt – and the multilateral approach to that has frayed at the edges, with the US departing from the Paris Agreement. I wish that hadn’t happened, but the economics of the cleaner alternative that we’re building just get better and better over time – and it’s obvious that that’s the way you should head.

Pete Betts, who I knew very well, was for a long time, the head of the whole climate effort – when it came to the multilateral discussion on climate. I always remember he said to me – and this was before he was diagnosed and sadly died – he said look, it’s all heading in one direction, this stuff, you’ve just got to keep remembering that. The COP, which is often the kind of touch point for this – I know you go every year, Simon – you know, he said, I always remember Pete said this, “you’ve got to see the movie, not the scene”. The movie is that things are heading in one direction, towards something cleaner. Good luck if you think you can avoid that – King Canute standing, trying to make the waves stop, the waves lapping over him. But the scene is often the thing that we talk about, if it’s the COP or the latest pronouncement from the US on the Paris Agreement. These are disappointing scenes in that movie, but the movie still ends in the right place, it seems to me, so we’ve got to stay focused on that ending.

CB: Brilliant, thanks very much, Chris.

The post Chris Stark: The economics of clean energy ‘just get better and better’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Chris Stark: The economics of clean energy ‘just get better and better’

Greenhouse Gases

Guest post: The challenges in projecting future global sea levels

It is well understood that human-caused climate change is causing sea levels to rise around the world.

Since 1901, global sea levels have risen by at least 20cm – accelerating from around 1mm a year for much of the 20th century to 4mm a year over 2006-18.

Sea level rise has significant environmental and social consequences, including coastal erosion, damage to buildings and transport infrastructure, loss of livelihoods and ecosystems.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has said it is “virtually certain” that sea level will continue to rise during the current century and beyond.

But what is less clear is exactly how quickly sea levels could climb over the coming decades.

This is largely due to challenges in calculating the rate at which land ice in Antarctica – the world’s largest store of frozen freshwater – could melt.

In this article, we unpack some of the reasons why projecting the speed and scale of future sea level rise is difficult.

Drivers of sea level rise

There are three principal components of sea level rise.

First, as the ocean warms, water expands. This process is known as thermal expansion, a comparatively straightforward physical process.

Second, more water gets added to the oceans when the ice contained in glaciers and ice sheets on land melts and flows into the sea.

Third, changes in rainfall and evaporation – as well as the extraction of groundwater for drinking and irrigation, drainage of wetlands and construction of reservoirs – affect how much water is stored on land.

In its sixth assessment cycle (AR6), the IPCC noted that thermal expansion and melting land ice contributed almost equally to sea level rise over the past century. Changes in land water storage, on the other hand, played a minor role.

However, the balance between these three drivers is shifting.

The IPCC projects that the contribution of melting land ice – already the largest contributor to sea level rise – will increase over the coming decade as the world continues to warm.

The lion’s share of the Earth’s remaining land ice – 88% – is in Antarctica, with Greenland accounting for almost all of the rest. (Mountain glaciers in the Himalaya, Alps and other regions collectively account for less than 1% of total land ice.)

However, it is difficult to project exactly how much Antarctic ice will make its way into the sea between now and 2100.

As a result, IPCC projections cover a large range of outcomes for future sea level rise.

In AR6, the IPCC said sea levels would “likely” be between 44-76cm higher by 2100 than the 1995-2014 average under a medium-emissions scenario. However, it noted that sea level rise above this range could not be ruled out due to “deep uncertainty linked to ice sheet processes”.

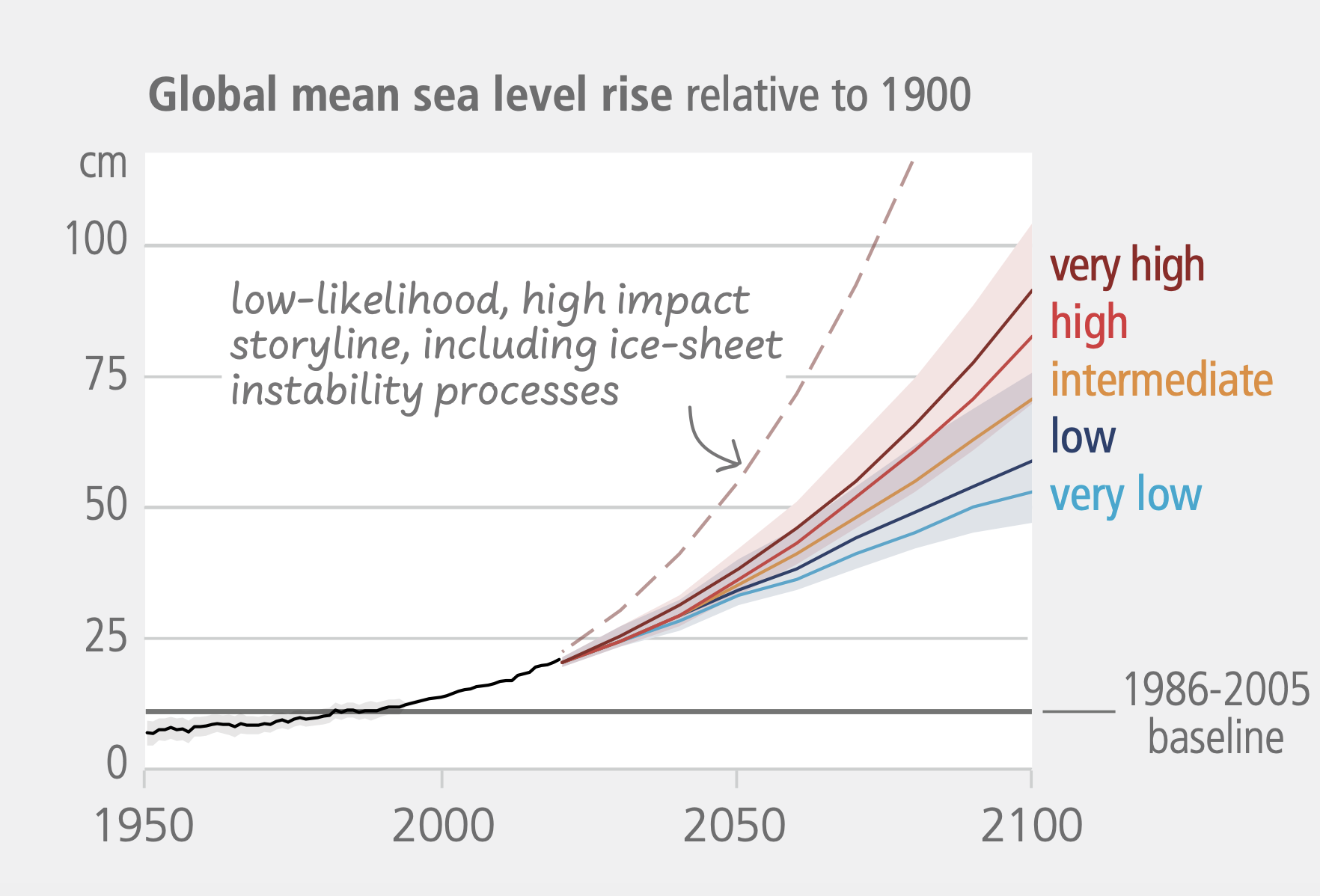

The chart below illustrates the wide range of sea level rise projected by the IPCC under different warming scenarios (coloured lines) as well as a possible – but unlikely – worst-case scenario (dotted line).

The shaded areas represent the “likely range” of sea level rise under each warming scenario, calculated by analysing processes that are already well understood. The worst-case scenario dotted line represents a future where various poorly understood processes combine to lead to a very rapid increase in sea levels.

The graph shows that sea level rise increases with warming – and would climb most sharply under the “low-likelihood, high-impact” pathway.

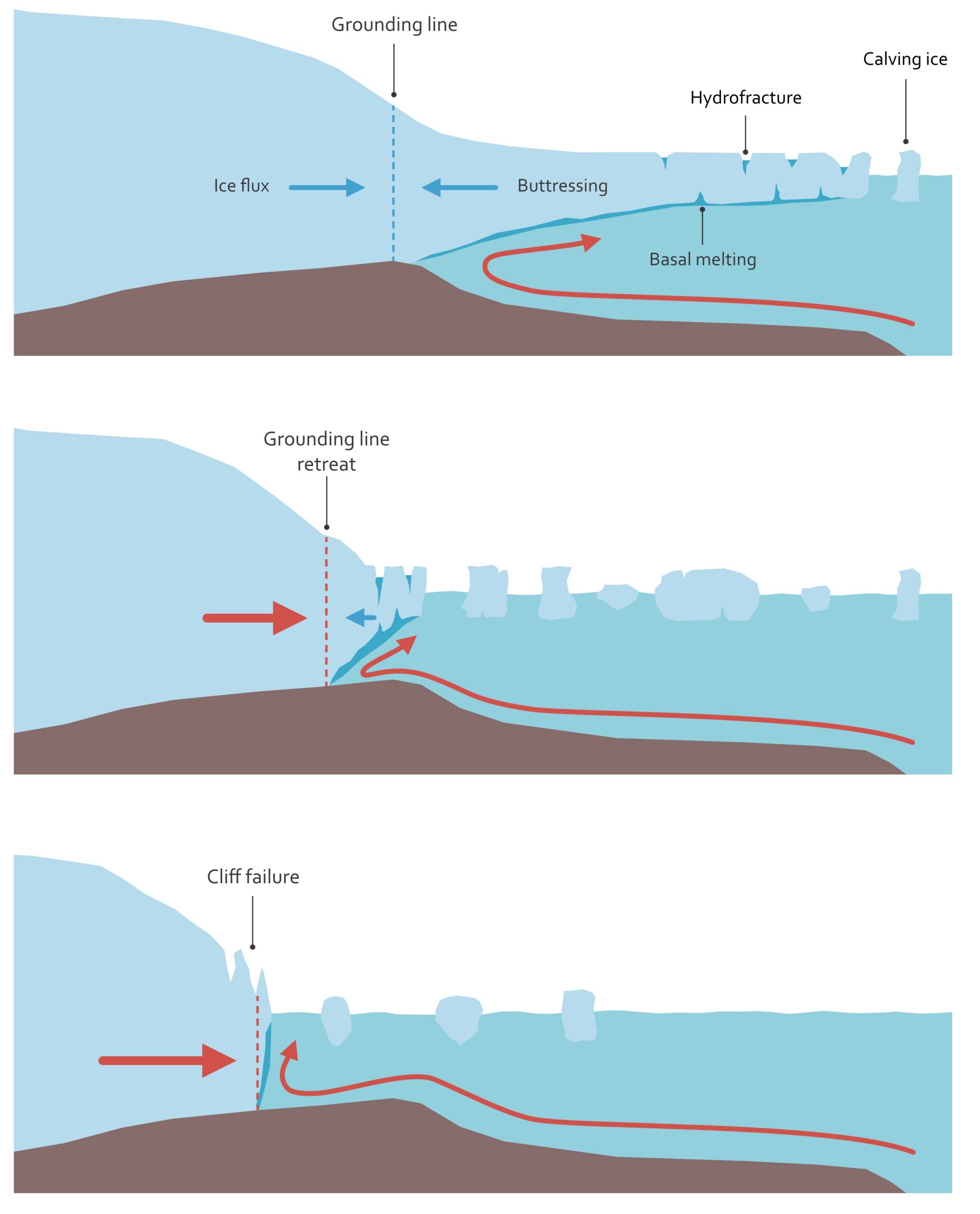

Retreat of glacier grounding lines

In Antarctica, the melting of ice on the surface of glaciers is limited. In many locations, warmer temperatures are leading to increases in snowfall and greater snow accumulation, which means the surface of the ice is continuously gaining mass.

Most of Antarctica’s contribution to global sea level rise is, therefore, not linked to ice melt at the surface. Instead, it occurs when giant glaciers push from land into the sea, propelled downhill by gravity and their own immense weight.

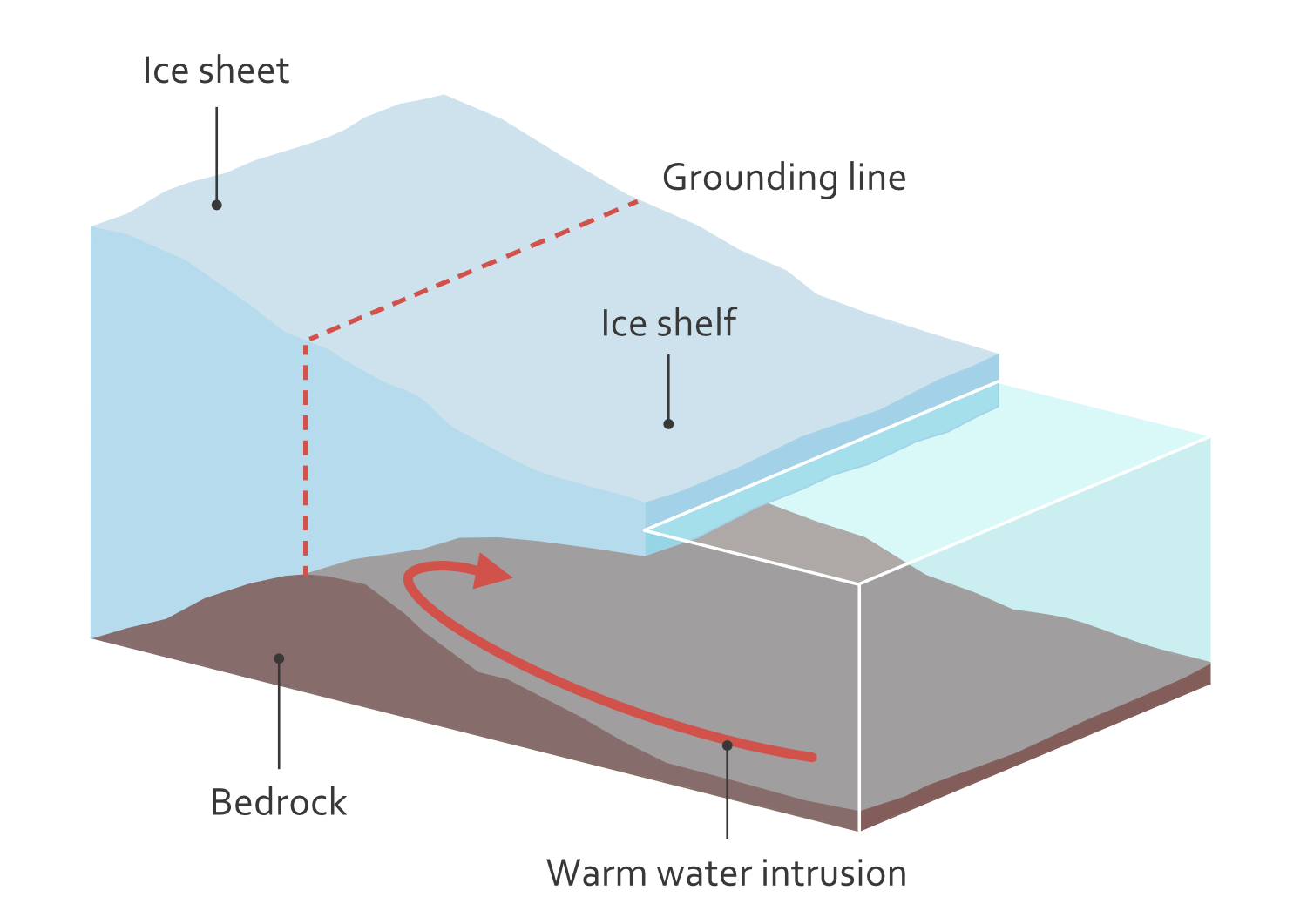

These huge masses of ice first grind downhill across the land and then along the seafloor. Eventually, they detach from the bedrock and start to float.

These floating ice shelves then largely melt from below, as warm ocean water intrudes into cavities on its underside. This is known as “basal melting”.

The boundary between grounded and floating ice is known as the “grounding line”.

In many regions of Antarctica, grounding lines typically sit at the high point of the bedrock, with the ice sheet deepening inland. This is illustrated in the graphic below.

When a grounding line is at a high point of the bedrock, it acts as a block which limits the area of ice exposed to basal melting.

However, if the grounding line retreats further inland, warm water could “spill” over the high point in the bedrock and carve out large cavities below the ice. This could dramatically accelerate the retreat of grounding lines further inland across Antarctica.

There is evidence to suggest that the retreat of grounding lines might cause a runaway effect, in which each successive retreat causes the ice behind the line to detach from the land even more quickly.

Recent climate modelling suggests that many grounding lines are not yet in runaway retreat – but some regions of Antarctica are close enough to thresholds that tiny increases in basal melting push model runs toward very different outcomes.

Whether – and to what extent – grounding lines might retreat will depend on a wide range of factors, including the exact shape of the bedrock beneath the ice. However, the bedrock on the coast of Antarctica has not yet been precisely mapped in many places.

Ice shelves

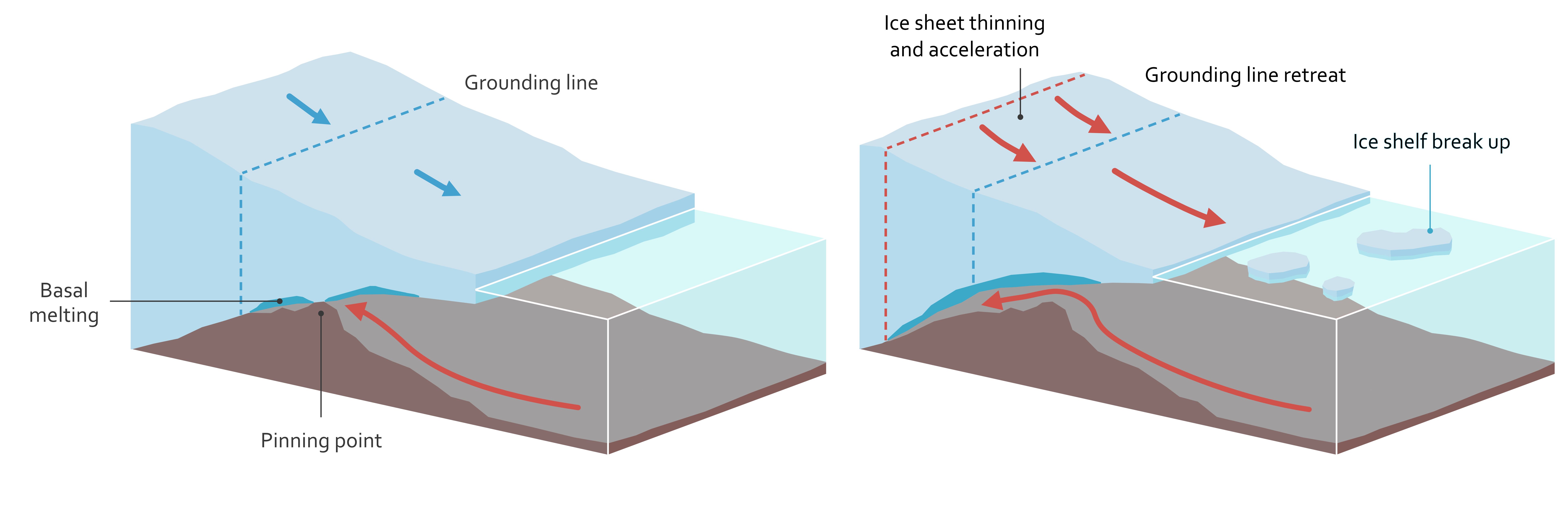

Once Antarctic ice detaches from the seabed, it floats on the ocean surface. These floating ice shelves slow the flow of ice from land towards the sea, acting as a brake as they wedge between headlands and little hills on the seafloor.

If these ice shelves break apart, the flow of glaciers towards the sea can accelerate.

The image below on the left shows a present-day ice shelf that is pinned in place by bedrock, which slows the flow of the ice into the sea.

The image on the right shows a future scenario in which ocean water continues to intrude under the ice, accelerating basal melting on the underside of the floating ice until it completely detaches from the “pinning point” that had previously held it in place.

In this scenario, the bedrock is no longer acting as a break on glaciers pushing to the sea and the ice shelf starts flowing into the sea more quickly and begins breaking up. Ice masses inland then begin to push more rapidly towards the sea.

This dynamic was directly observed during the collapse of the Larsen-B ice shelf on the Antarctic Peninsula in 2002, which led to accelerated glacial ice flow and is believed to have contributed to a dramatic glacial retreat two decades later.

However, the factors affecting the stability of the floating ice shelves around Antarctica’s coast are complex. The strength of ice shelves depends on their thickness, how and where they are pinned to the seafloor, how cracks grow, as well as air and sea temperatures and levels of snow and rainfall. For example, meltwater at the surface can lever cracks further apart, in a process known as hydrofracturing.

A 2024 review of the stability of ice shelves found big gaps in scientific understanding of these processes. There is currently no scientific consensus on how rapidly various ice shelves might collapse – the pace is likely to vary greatly from one ice shelf to the next.

Ice-cliff collapse